Lire l`article complet

196 | La Lettre du Neurologue • Vol. XVI - n° 6 - juin 2012

DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE

Neuro-gynécologie

Méningiomes

et hormonodépendance

Meningiomas and hormonal dependency

G. Kaloshi*, P. Ciccarino**, M. Rossetto**, M. Sanson***

* Clinique neurochirurgicale, hôpital

Mère-Teresa, Tirana, Albanie.

** Clinique neurochirurgicale, univer-

sité de Padoue, Italie.

*** Service de neurologie II, hôpital

de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris.

Généralités

Les méningiomes représentent environ un tiers

des tumeurs intracrâniennes. En réalité, la décou-

verte fortuite, chez le sujet âgé, est une éventualité

fréquente (1 %) qui suggère une incidence beaucoup

plus importante. Les méningiomes sont 2 à 3 fois

plus fréquents chez la femme.

Ils se développent à partir des cellules arachnoïdiennes

des méninges qui entourent le cerveau et la moelle

épinière. Les méningiomes sont classés en 3 grades

suivant la classication OMS : le grade I (bénin, > 90 %

des cas), le grade III (anaplasique, 1 à 3 % des cas), et

le grade II intermédiaire (atypique, 5 à 7 % des cas).

La prévalence féminine est observée uniquement

dans les méningiomes de grade I, les formes méningo-

théliales, broblastiques et transitionnelles consti-

tuant les plus fréquentes. En revanche, on observe

une discrète prépondérance masculine dans les

grades II et III.

À côté des rares formes liées à la neurofibro-

matose de type II et d’exceptionnels cas de ménin-

giomes familiaux, un locus a été identifié sur le

chromosome 10, récemment associé à la survenue

de méningiomes sporadiques (1). Parmi les facteurs de

risque environnementaux, en dehors du rôle possible

des hormones exogènes (cf. infra), le principal facteur

de risque de méningiome est constitué par les radia-

tions ionisantes, notamment chez des patients ayant

été traités dans l’enfance pour une leucémie ou un

médulloblastome.

Sur le plan moléculaire, l’altération la plus fréquente

est l’inactivation du gène NF2, présente dans plus

de la moitié des méningiomes. Le rôle clé de l’inac-

tivation du gène NF2 a été clairement établi dans

la tumorigenèse méningée. Les méningiomes de

grades II et III sont caractérisés par des anomalies

génétiques additionnelles (2).

On distingue, sur le plan anatomique, les ménin-

giomes de la convexité et les méningiomes de la

base du crâne, plus difciles d’accès, mais souvent

aussi d’évolution plus lente, et très rarement de

grade II ou III.

Le traitement repose sur la chirurgie. Le taux de

récidives est étroitement lié au caractère complet de

l’exérèse et au grade histologique de la tumeur. La

radiothérapie est indiquée en cas de tumeur évolutive

et de localisation inaccessible, ou incomplètement

accessible à la chirurgie. À l’heure actuelle, aucun

traitement médical n’a réellement fait la preuve de

son efcacité, en dehors de cas isolés, qu’il s’agisse

de la chimiothérapie (hydroxyurée notamment), des

antiangiogéniques (bévacizumab) dans les grades II

et III, ou des traitements hormonaux (cf. infra) dans

les grades I.

Récepteurs hormonaux

dans les méningiomes

L’hormonodépendance des méningiomes est d’abord

suggérée par des observations cliniques : prévalence

plus importante chez la femme, accélération de la crois-

sance observée pendant la grossesse ou la deuxième

phase du cycle, association, encore controversée, entre

méningiome et cancer du sein. Ces données suggèrent

avant tout une dépendance à la progestérone.

La présence de récepteurs de la progestérone a en

effet été rapportée dans les méningiomes dès les

années 1980 (3) et apparaît plus fréquente chez la

femme (80 %) que chez l’homme (40 %). Le taux,

élevé dans la majorité des méningiomes de grade I,

notamment le sous-type méningothélial, est inver-

sement corrélé au grade, et les méningiomes de

grades II et III sont habituellement dépourvus de

récepteurs à la progestérone.

La Lettre du Neurologue • Vol. XVI - n° 6 - juin 2012 | 197

Points forts

»

La prédominance des méningiomes chez les femmes, l’accélération rapportée pendant la grossesse,

l’association entre méningiome et cancer du sein suggèrent que les hormones stéroïdes, notamment les

progestatifs, jouent un rôle dans la croissance des méningiomes.

»

De nombreuses études ont été réalisées in vitro avec des résultats souvent contradictoires. Bien que

la majorité des méningiomes expriment les récepteurs à la progestérone, seul un petit nombre semble

répondre à un traitement antiprogestatif.

»

Le rôle de la contraception estroprogestative et du traitement hormonal substitutif demeure controversé

suivant les études. Cependant, ils pourraient être associés à une augmentation du risque de développe‑

ment de méningiomes.

Mots‑clés

Méningiomes

Récepteurs

à la progestérone

Grossesse

Traitement

estroprogestatif

Highlights

»

Higher prevalence in female,

growth acceleration reported

during pregnancy, association

of meningiomas with breast

cancer suggests that steroids,

and particularly progesterone,

may be involved in menin-

giomas growth.

»

Despite the majority of

meningiomas express proges-

terone receptors, only a small

percentage respond to antipro-

gestative therapy.

»

Although it still remains

controversial, estroprogestative

treatment may be associated

with meningioma risk.

Keywords

Meningiomas

Progesterone receptors

Pregnancy

Estroprogestative treatment

La localisation nucléaire suggère dans la majorité

des cas que ces récepteurs sont fonctionnels. Des

études pré cliniques, effectuées sur des cellules en

culture et sur la xénogreffe de souris, suggèrent, en

dépit de quelques résultats contradictoires, que la

progesté rone stimule la croissance des méningiomes

et que les antagonistes (notamment la mifépristone)

bloquent la croissance (2).

Le rôle des récepteurs aux estrogènes et aux

androgènes est beaucoup moins bien établi : ils

sont retrouvés dans moins de la moitié des cas, à

un taux faible. D’ailleurs, le traitement des ménin-

giomes par tamoxifène n’a donné lieu à aucun

résultat probant. En dehors des récepteurs aux

stéroïdes, les méningiomes expriment fortement

des récepteurs à la somatostatine : ils peuvent être

mis en évidence par scintigraphie à l’octréotide. En

revanche, leur rôle dans la croissance des ménin-

giomes n’est pas clairement établi. De rares cas de

réponses à l’octréotide ont été rapportés dans la

littérature. Récemment, un essai de phase I a testé

l’octréotide sur 11 patients, et aucune réponse n’a

été observée (4).

Impact de la grossesse

L’aggravation au cours de la grossesse a souvent été

rapportée. Une part de cette aggravation, commune

à toutes les tumeurs, est liée à une augmentation

du compartiment tumoral extracellulaire, réversible

en post-partum. La régression de la taille tumorale

en post-partum peut être aussi due à la baisse du

taux de progestérone (5). En dehors de cet effet

transitoire et réversible, l’impact de la grossesse

sur la croissance du méningiome à moyen et à long

terme n’est pas établi. En effet, la prévalence du

méningiome a été associée au nombre de grossesses

antérieures (6), avec un risque relatif de 1,8 chez les

femmes ayant eu 3 enfants ou plus par rapport aux

nullipares, alors que d’autres études ne trouvent pas

de lien (7), ou même suggèrent au contraire un rôle

protecteur (8).

En conclusion, c’est surtout le risque d’aggravation

en cours de grossesse qui apparaît bien établi ;

l’impact sur l’évolution de la maladie à long terme

n’est en revanche pas démontré. En cas de locali-

sation menaçante et difcilement accessible (fosse

postérieure, trou occipital, apex orbitaire), ce risque

d’aggravation devra être pris en compte, la patiente

sera informée et l’intervention sera discutée avec le

neurochirurgien (9).

Association entre méningiome

et cancer du sein

L’association cancer du sein et méningiome a été

suggérée par plusieurs études (le risque relatif,

respectivement, de cancer du sein chez les patientes

porteuses d’un méningiome, et de méningiome chez

les patientes traitées pour un cancer du sein est de

1,5) [10, 11]. Cette association ne signie pas pour

autant un lien avec les hormones sexuelles : elle peut

être due à des facteurs environnementaux autres ou

à des facteurs génétiques. Quoi qu’il en soit, il s’agit

d’un risque relatif très faible.

Impact du traitement

estroprogestatif (contraception

orale et traitement hormonal

substitutif)

Une vaste étude de cohorte suggère un lien, avec

une fréquence de 865 méningiomes pour 100 000

chez les femmes ayant ou ayant eu un traitement

estroprogestatif versus 366 pour 100 000 pour les

femmes non traitées, ce qui correspond à un risque

relatif de 2,2 pour l’ensemble de la population, mais

de 4 pour les femmes de moins de 55 ans (12),

conrmant des études antérieures (7). Toutefois, ce

lien n’est pas retrouvé par d’autres auteurs (13, 14),

certains suggérant même un effet protecteur de la

contraception orale (8).

En dépit de ces discordances, il faut considérer un

traitement contenant des progestatifs comme

pouvant possiblement favoriser la croissance

tumorale. S’il s’agit d’un méningiome opérable et

ayant bénécié d’une exérèse complète, rien n’interdit

un traitement estroprogestatif (en prévoyant un suivi

radiologique). S’il s’agit d’une tumeur inopérable, et a

fortiori d’une localisation menaçante, tout traitement

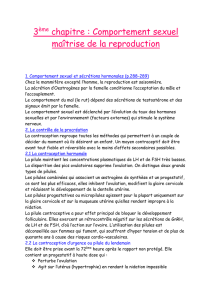

Figure. A. Patiente de 55 ans traitée pour une méningiomatose (convexité et sphénoïdal

gauche). B. Nette diminution de taille des lésions après 9 mois de traitement par la

mifépristone (RU486). La patiente est toujours contrôlée après 6 ans de traitement.

AB

Méningiomes et hormonodépendance

DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE

Neuro-gynécologie

progestatif doit être suspendu. Entre ces 2 situations,

il faudra peser les bénéces et les risques, et choisir,

le cas échéant, le plus faible dosage en progestatifs.

Conséquence thérapeutique :

traitement des méningiomes

par antiprogestatifs

Bien que la majorité des méningiomes bénins

expriment les récepteurs à la progestérone, l’effet

des antiprogestatifs, suggéré par 2 études en

ouvert (15-17), s’est révélé modeste et n’a pu être

conrmé dans 2 études randomisées menées secon-

dairement (et non publiées), mais cela peut être

expliqué par un manque de puissance de l’étude,

et l’absence de sélection des patients (par exemple,

l’expression d’un taux élevé de récepteur à la

progestérone semble être une condition nécessaire,

quoique non sufsante). Toutefois, le suivi au long

cours suggère un bénéce modeste chez 8 patients,

notamment chez les femmes non ménopausées (16).

Par ailleurs, il existe des cas incontestables de

méningiomes qui ont répondu au traitement par

antiprogestatif (mifépristone [17β-hydroxy-11β-(4-

dimethylaminophenyl)-17α-(prop-1-ynyl)estra-4,9-

dien-3-one], ou RU486), voire un cas rapporté de

régression d’une méningiomatose après simplement

l’arrêt d’un traitement progestatif (18). De façon

intéressante, c’est également dans le cas d’une ménin-

giomatose que nous avons observé la réponse la plus

nette au RU486 (figure).

Ces cas isolés renforcent la preuve de concept

d’un traitement antiprogestatif des méningiomes.

L’identification des méningiomes dépendant de

la progestérone et candidats à un tel traitement

requiert probablement une analyse biologique plus

ne, prenant en compte des molécules corégulatrices

qui pourraient expliquer l’hétérogénéité de la réponse

aux antiprogestérones (19, 20).

Conclusion

Bien que l’hormonosensibilité des méningiomes et

la présence des récepteurs à la progestérone soient

connues depuis 30 ans, il n’y a pas eu, dans ce

domaine, d’avancées majeures. En effet, l’hétéro-

généité de la réponse aux antiprogestérones est

encore très mal connue. En attendant les progrès à

venir, la prise en charge du méningiome repose sur

la chirurgie et la radiothérapie. Dans l’impossibilité

de prédire l’hormonodépendance d’un méningiome

donné, la poursuite ou l’arrêt d’un traitement estro-

progestatif doivent être discutés, au cas par cas, entre

le neurologue et le gynécologue. ■

1. Dobbins SE, Broderick P, Melin B et al. Common variation

at 10p12.31 near MLLT10 influences meningioma risk. Nat

Genet 2011;43:825-7.

2. Sanson M, Cornu P. Biology of meningiomas. Acta Neurochir

(Wien) 2000;142:493-505.

3. Magdelenat H, Pertuiset BF, Poisson M et al. Progestin and

oestrogen receptors in meningiomas. Biochemical charac-

terization, clinical and pathological correlations in 42 cases.

Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1982;64:199-213.

4. Johnson DR, Kimmel DW, Burch PA et al. Phase II study of

subcutaneous octreotide in adults with recurrent or progres-

sive meningioma and meningeal hemangiopericytoma.

Neuro-Oncology 2011;13:530-5.

5. Smith JS, Quiñones-Hinojosa A, Harmon-Smith M et al. Sex

steroid and growth factor profile of a meningioma associated

with pregnancy. Can J Neurol Sci 2005;32:122-7.

6. Wigertz A, Lönn S, Hall P et al. Reproductive factors and

risk of meningioma and glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers

Prev 2008;17:2663-70.

7. Michaud DS, Gallo V, Schlehofer B et al. Reproductive

factors and exogenous hormone use in relation to risk of

glioma and meningioma in a large European cohort study.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:2562-9.

8. Lee E, Grutsch J, Persky V et al. Association of meningioma

with reproductive factors. Int J Cancer 2006;119:1152-7.

9. Kanaan I, Jallu A, Kanaan H. Management strategy for menin-

gioma in pregnancy: a clinical study. Skull Base 2003;13:197-204.

10. Custer BS, Koepsell TD, Mueller BA. The association

between breast carcinoma and meningioma in women.

Cancer 2002;94:1626-35.

11. Rao G, Giordano SH, Liu J et al. The association of breast

cancer and meningioma in men and women. Neurosurgery

2009;65:483-9.

12. Blitshteyn S, Crook JE, Jaeckle KA. Is there an association

between meningioma and hormone replacement therapy?

J Clin Oncol 2008;26:279-82.

13. Cea-Soriano L, Blenk T, Wallander MA et al. Hormonal

therapies and meningioma: is there a link? Cancer Epidemiol

2012;36:198-205.

14. Custer B, Longstreth WT, Phillips L et al. Hormonal expo-

sures and the risk of intracranial meningioma in women: a

population-based case-control study. BMC Cancer 2006;6:1-9.

15. Grunberg SM, Weiss MH, Spitz IM et al. Treatment of

unresectable meningiomas with the antiprogesterone

agent mifepristone. J Neurosurg 1991;74:861-6.

16. Grunberg SM, Weiss MH, Russell CA et al. Long-term

administration of mifepristone (RU486): clinical tolerance

during extended treatment of meningioma. Cancer Invest

2006;24:727-33.

17. Lamberts SW, Koper JW, de Jong FH. The endocrine

effects of long-term treatment with mifepristone (RU486).

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1991;73:187-91.

18. Vadivelu S, Sharer L, Schulder M. Regression of

multiple intracranial meningiomas after cessation of

long-term progesterone agonist therapy. J Neurosurg

2010;112:920-4.

19. Carroll RS, Brown M, Zhang J et al. Expression of a

subset of steroid receptor cofactors is associated with

progesterone receptor expression in meningiomas. Clin

Cancer Res 2000;6:3570-5.

20. Claus EB, Park PJ, Carroll R et al. Specific genes

expressed in association with progesterone receptors in

meningioma. Cancer Res 2008;68:314-22.

Références bibliographiques

1

/

3

100%