Marqueurs de discours - Université Paris

!"#$%&%#'()&()*'+,%#'(

-.&/&0(-+1"&2&#(

30*/&#'*.4(5"#*'6-,#7,00&(

89:;!<=>(

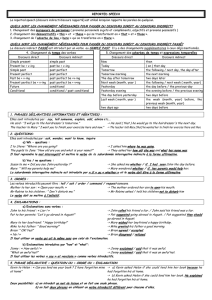

8&'(?"#$%&%#'()&()*'+,%#'(@"#&0.14A$%&'(B(

!"#$%"#&'()"*+,"-%(.&%.($/"/&01)2/3*4(

• C4.4#,DE0&'(F(%0(D#"0)(0,?7#&()&('.#%+.%#&'(

@,''*7G&'(

• HIG&('&+,0)"*#&(@"#(#"@@,#.("%J(@#,@,'*A,0'(

G&J*+"G&'(

• 5,''*7*G*.4()K,++%##&0+&()"0'(@G%'*&%#'(

@,'*A,0'(@"#(#"@@,#.("%J(@#,@,'*A,0'(

@#*0+*@"G&'(

5#,7G4?"A$%&(

• L&'(&J@#&''*,0'(',0.(+,0'A.%A/&'(&0(@"#A&()&(

G"(+,14#&0+&()%()*'+,%#'(

• MGG&'(',0.(,?0*@#4'&0.&'()"0'(G&()*'+,%#'(

'@,0."04(+,0.&?@,#"*0(

• NG(&'.(*?@,#."0.()&(+�&#(G&%#(#IG&(&.(2,0+A,0(

&0()*'+,%#'(F(@G%'*&%#'("J&'()K"@@#,+1&(

*0+G%&0.(G"(G*0D%*'A$%&('4?"0A+,6'O0."J*$%&P(

G"(@#,',)*&P("/&+(%0&(@#*'&(&0(+,?@.&()%(

+,0.&J.&(Q@#"D?"A$%&(&.(40,0+*"A2R(

5,'*A,0(Q'*?@G*S&4R()"0'(GK40,0+4(

• N;NT:8M(

• 5&+,6*78&5&7*398&5&:".6";"&

&&Q'O0."+A+(?".#*JR(F('%7,#)*0".&(@#,@,'*A,0(

• !MUN:;M(

• 5"#&0.1&A+"G(:)V%0+.(6(5&+,6*78&5&7*398&5&:".6";"&

QW()*'@G"+&)(?".#*J(X(R(F(Y*.1*0(,#(7&.Y&&0(

@#,@,'*A,0Q'R(

• ZN;:8M(

• ?"*0(@#,@,'*A,0(6(5&+,6*78&5&7*398&5&:".6";"&

QV%J."@,'&)('%@@G&?&0."#O(+,??&0.(+G"%'&R((

T,0O([G"*#P(D,,)("\�,,0](M#P(N(&0V,O&)(.1&(7,,^P(&#(N(?&"0(.1".('*0+&#&GO_(N.K'($%*.&(#&2#&'1*0D(5&

+,6*7_(N.K'(%0G*^&`(,.1&#(@,G*A+"G(?&?,*#'_((

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

1

/

25

100%