Innovative Policy Regoverning Markets Canada Maple syrup production in Quebec: Farmer

Canada

Maple syrup production in Quebec: Farmer

self-determination for market control

Isabelle Gagné

L’Union des producteurs agricoles (UPA)

www.regoverningmarkets.org

Innovative Policy

Regoverning Markets

Small-scale producers in modern agrifood markets

MaplesyrupproductioninQuebec

Farmerself‐determinationformarketcontrol

IsabelleGagné

UPADirectiondelaCommercialisation

1

RegoverningMarkets

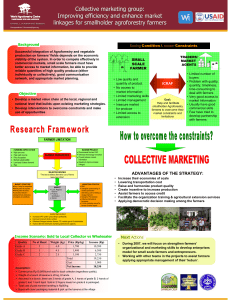

RegoverningMarketsisamulti‐partnercollaborativeresearchprogrammeanalysingthegrowing

concentrationintheprocessingandretailsectorsofnationalandregionalagrifoodsystemsandits

impactsonrurallivelihoodsandcommunitiesinmiddle‐ andlow‐incomecountries.Theaimof

theprogrammeistoprovidestrategicadviceandguidancetothepublicsector,agrifoodchain

actors,civilsocietyorganizationsanddevelopmentagenciesonapproachesthatcananticipate

andmanagetheimpactsofthedynamicchangesinlocalandregionalmarkets.

InnovativePolicyseries

InnovativePolicyisaseriesofshortstudiesfromtheRegoverningMarketsprogramme

addressingaspecificpolicyinnovationinthepublicorprivatesectorthatimprovestheconditions

forsmall‐scaleproducerstoaccessdynamicmarketsatnational,regionalandgloballevel.

Thecasestudieswerecoordinatedby:

JulioBerdegué,RIMISP‐LatinAmericanCentreforRuralDevelopment,Chile(contact:

LucianPeppelenbos,RoyalTropicalInstitute(KIT),Netherlands(contact[email protected])

EstelleBiénabe,CentredeCoopérationInternationaleenRechercheAgronomiquepourle

Développement(CIRAD),France(contact:[email protected])

OtherpublicationseriesfromtheRegoverningMarketsprogramme

InnovativePractice

InnovativePracticeisaseriesofcountrycasestudiesprovidingexamplesofspecificinnovationin

connectingsmall‐scaleproducerswithdynamicmarketsatlocalorregionallevel.Basedon

significantfieldworkactivities,thestudiesfocusonfourdriversofinnovation:publicpolicy

principles,privatebusinessmodels,collectiveactionstrategiesbysmall‐scalefarmers,and

interventionstrategiesandmethodsofdevelopmentagencies.Thestudieshighlightpolicylessons

andworkingmethodstoguidepublicandprivateactors.

AgrifoodSectorStudies

Thesestudieslookatspecificagrifoodsectorswithinacountryorregion.Researchstudieshave

beencarriedoutinChina,India,Indonesia,Mexico,SouthAfrica,Turkey,PolandandZambia

coveringthehorticulture,dairyandmeatsectors.PartAofthestudiesdescribetheobserved

marketrestructuringalongthechains.PartBexploresthedeterminantsofsmall‐scalefarmer

inclusioninemergingmodernmarkets.Usingquantitativesurveytechniques,theyexplorethe

impactsonmarketingchoicesoffarmers,andimplicationsforruraldevelopment.

CountryStudies

Theseprovideasummaryofmarketchangestakingplaceatnationallevelwithinkeyhigh‐value

agrifoodcommoditychains.

FurtherinformationandpublicationsfromtheRegoverningMarketsprogrammeareavailableat:

www.regoverningmarkets.org.

Author

IsabelleGagné,UPADirectiondelaCommercialisation

2

Acknowledgments

Fundingforthisworkwasprovidedby:

UKDepartmentforInternationalDevelopment(DFID)

InternationalDevelopmentResearchCentre(IDRC),Ottawa,Canada

ICCO,Netherlands

Cordaid,Netherlands

CanadianInternationalDevelopmentAgency(CIDA)

USAgencyforInternationalDevelopment(USAID).

Theviewsexpressedinthispaperarenotnecessarilythoseofthefundingagencies.

Citation:GagneI(2008).MaplesyrupproductioninQuebec:Farmerself‐determinationfor

marketcontrol,RegoverningMarketsInnovativePolicyseries,IIED,London.

Permissions:Thematerialinthisreportmaybereproducedfornon‐commercialpurposes

providedfullcreditisgiventotheauthorsandtheRegoverningMarketsprogramme.

Publishedby:

SustainableMarketsGroup

InternationalInstituteforEnvironmentandDevelopment(IIED)

3EndsleighStreet

LondonWC1H0DD

www.iied.org

Tel:+44(0)2073882117,email:[email protected]

Coverdesign:smith+bell

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

1

/

27

100%