Lire l'article complet

114

La Lettre de l’Infectiologue - Tome XVII - n° 4 - avril 2002

MISE AU POINT

a richesse, le polymorphisme et la plasticité du

génome de Plasmodium falciparum (1), agent le plus

répandu du paludisme et responsable des formes cli-

niques pernicieuses, lui confèrent des capacités adaptatives

absolument remarquables. Elles lui permettent de développer,

extrêmement rapidement, des phénomènes d’échappement et

de résistance vis-à-vis des stress auxquels il est soumis. Cette

capacité du parasite lui est particulièrement bénéfique dans deux

domaines :

!L’évitement de la pression immunologique. Cela explique

l’inefficacité relative du système immunitaire contre lui (2) et

rend problématique la mise au point d’un vaccin.

!La résistance aux médicaments. Par exemple, les mutations

ponctuelles sur le gène de la dihydrofolate réductase (DHFR)

empêchent l’action de la pyriméthamine (3, 4), l’augmentation

du nombre de copies du gène pfmdr1 facilite l’expulsion de

la méfloquine ou de l’halofantrine (5, 6), les modifications

polygéniques sur le chromosome 7 (gènes cg2, crt) inhibent

l’action de la chloroquine (4).

Pour continuer à disposer d’armes thérapeutiques efficaces

contre le paludisme, médecins et scientifiques ont orienté leurs

travaux dans plusieurs directions :

!L’identification de métabolismes spécifiques a conduit à la

recherche de nouvelles molécules ciblant, par exemple, la syn-

thèse des phospholipides (7) ou les enzymes du système de

défense contre les espèces activées de l’oxygène (8, 9).

!L’amélioration des performances de médicaments existants

a abouti à la mise au point de dérivés pouvant, en particulier,

contrecarrer les mécanismes de résistance développés par le

parasite : exemple des dérivés ferrocéniques (10).

!La caractérisation des principes actifs contenus dans des

extraits naturels efficaces, issus de la pharmacopée tradition-

nelle, a amené, par exemple, à la découverte du quinghaosu (11).

!L’association synergique de molécules déjà connues pour

leurs activités antimalariques, afin d’éviter les phénomènes de

recrudescence et de limiter la sélection de souches résistantes.

À ce titre, Riamet®et Malarone®ont récemment été proposés.

RIAMET®

Le projet qui unit depuis 1994 l’Institut de microbiologie et

d’épidémiologie de Pékin, Kunmig Pharmaceutical Corpora-

tion, Cititech et Novartis a permis le développement du co-

artéméther (ou Riamet®) qui associe, pour l’administration par

voie orale, l’artéméther et la luméfantrine.

L’artéméther est un dérivé semi-synthétique de l’artémisinine

(ou quinghaosu), qui est le principe actif d’une plante, Artemi-

sia annua (ou quinghao). Les propriétés antipaludiques de cette

plante avaient été révélées en 1971 par les Chinois, qui l’utili-

saient depuis fort longtemps pour ses propriétés antipyrétiques.

L’artéméther est un endoperoxyde du groupe des sesquiterpènes-

lactones, appartenant à la famille des trioxanes, et qui, selon toute

probabilité, agit par la production de radicaux libres de l’oxy-

gène, à la suite de la fixation à l’hème et à son atome de fer (9-

12). Les espèces activées de l’oxygène provoquent chez le para-

site une dénaturation des protéines et la formation de ponts

amino-iminopropènes (AIP) par peroxydation lipidique au niveau

des membranes (12). L’artéméther est actif sur le parasite en situa-

tion intraérythrocytaire en raison de la formation du complexe

artémisinine-hème dans la vacuole digestive du parasite (12).

Il est clairement établi que la caractéristique essentielle de l’arté-

méther est sa rapidité d’action, par rapport à celle des autres anti-

Place des nouvelles associations dans la prophylaxie

et le traitement du paludisme : Riamet®et Malarone®

"

D. Camus*, E. Dutoit*, L. Delhaes*

*Faculté de médecine de Lille et Institut Pasteur de Lille, 59000 Lille.

RÉSUMÉ.

Le développement de la résistance de Plasmodium falciparum à de nombreux médicaments justifie la mise au point de nouveaux

traitements. Riamet®(association d’artéméther et de luméfantrine) et Malarone®(association d’atovaquone et de proguanil) se révèlent

efficaces vis-à-vis des souches parasitaires multirésistantes aux autres médicaments antipaludiques. Ils ont été testés, avec succès, chez des

sujets vivant dans diverses zones d’endémie palustre. Malarone®peut également être utilisé en prophylaxie avec l’avantage d’une part d’être

utilisable aussi bien dans les pays de la zone 2 que de la zone 3 et, d’autre part, avec une prescription limitée à une durée qui ne dépasse pas

7jours après avoir quitté la zone d’endémie.

Mots-clés :

Paludisme - Traitement - Chimioprophylaxie.

L

La Lettre de l’Infectiologue - Tome XVII - n° 4 - avril 2002

115

MISE AU POINT

malariques connus (13). Les études pharmacocinétiques montrent

que les doses plasmatiques maximales sont atteintes rapidement

(14), que la demi-vie est de l’ordre d’une quinzaine d’heures et

que le métabolisme aboutit à la formation de dihydro-artémisinine,

qui possède une activité antiparasitaire marquée (15).

La luméfantrine (ou benflumétol), synthétisée à l’origine par l’Aca-

démie militaire des sciences médicales de Pékin, comprend les

énantiomères dextrogyre et lévogyre du 2-dibutylamino-1-[2,7-

dichloro-9-(-4-chlorobenzylidène)-9H-fluoren-

4-yl]-éthanol. Sa conformation est proche de celle des aryl-amino-

alcools à propriétés antipaludiques, tels que la quinine, la méflo-

quine ou l’halofantrine. Sa structure laisse supposer que son méca-

nisme d’action serait assez proche de celui des autres antipaludiques

du même groupe, avec une demi-vie d’environ 4 à 5 jours (16).

Le bien-fondé du développement d’un médicament associant

artéméther et luméfantrine repose sur un enchaînement logique

d’arguments. Le paludisme à P. falciparum peut être mortel chez

les sujets non immuns, en particulier les enfants (17), et bien

souvent dans un délai relativement bref après l’admission à l’hô-

pital (18). Il est vrai que la quinine est souvent le médicament

de choix, mais elle agit relativement lentement et s’est avérée

inefficace dans un certain nombre de cas (19, 20). Dans certains

pays comme la Thaïlande, le problème de la résistance aux médi-

caments est crucial, avec la constatation de résistances impor-

tantes in vivo et in vitro vis-à-vis de la chloroquine, de la pyri-

méthamine-sulfadoxine, de la quinine, de l’halofantrine et de la

méfloquine (21). Pour répondre à ce besoin, de nouveaux médi-

caments, l’artémisinine et ses dérivés (artésunate et artéméther),

sont particulièrement intéressants, mais on a constaté qu’admi-

nistrés seuls, ces produits sont à l’origine d’un taux important

de rechutes à l’arrêt du traitement (22, 23). L’idée a donc été de

combiner ces molécules avec d’autres, capables d’assurer une

élimination totale de la population parasitaire portée par le sujet

infecté. L’association artémisinine-méfloquine répond à cet

objectif (23), mais devant la crainte de son inefficacité, en rai-

son d’une augmentation prévisible de la résistance des parasites

à la méfloquine, la recherche d’une nouvelle association s’est

trouvée justifiée. L’association artéméther-luméfantrine,

qui s’avère synergique (24), a ainsi été proposée et testée avec

succès dans les accès aigus non compliqués à P. falciparum en

Chine (25), Thaïlande (26), Tanzanie (27) et Gambie (28).

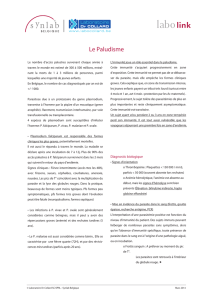

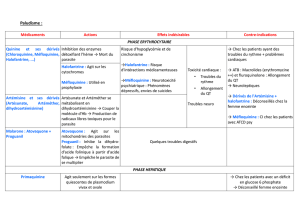

Les données bibliographiques regroupées dans le tableau I

permettent de tirer un certain nombre d’enseignements sur la

Tableau I. Efficacité de l’association artéméther-luméfantrine (AL) chez des sujets infectés par P. falciparum (Pf+). Analyse de données

bibliographiques.

Référence Caractéristique de l’étude Critère d’efficacité

Clairance Réapparition/ Données

parasitaire persistance des parasites complémentaires

29 "AL versus pyriméthamine-sulfadoxine (PS) à 3 j : Réapparition de parasites à 15 j : Génotypes différents dans 82,6 %

"287 enfants de 1 à 5 ans – 100 % avec AL 6,7 % avec AL ; 2,3 % avec PS des nouveaux accès

"Paludisme aigu, non compliqué, Pf+ – 93,4 % avec PS 2eaccès palustre à 3-4 semaines chez :

"Gambie 20 traités par AL ; 1 traité par PS

30 "AL (4 comprimés, 4 fois en 48 h) Mesure de la médiane : Réapparition de parasites à 28 j : Temps de clairance de la fièvre :

versus méfloquine (M) – AL : 43 h – AL : 30,7 % – AL : 32 h ; M : 54 h

"Paludisme aigu, non compliqué, Pf+ – M : 66 h – M : 17,6 % Temps de clairance des gamétocytes :

"Thaïlande, 252 patients – AL : 152 h ; M : 331 h

31 "AL : 4 comprimés, 4 fois en 48 h Mesure de la médiane : Persistance de parasites à 24 h : Temps de clairance de la fièvre :

versus halofantrine (H) – AL : 32 h – AL : 0,3 % ; H : 10,4 % – AL : 24 h ; H : 32 h

"103 patients (adultes, non immuns) – H : 48 h Réapparition de parasites à 28 j

"Paludisme aigu, non compliqué, Pf+ (pas de typage) :

– AL : 18 % ; H : 0 %

26 "AL versus artésunate-méfloquine (AM) à 3 j : 100 % Réapparition de parasites jusqu’à 63 j : Clairance de la fièvre

"617 patients (adultes et enfants) dans les deux groupes – 24,6 % avec AL dont 59 % de rechutes vraies entre 1 et 4 j dans les deux groupes

"Paludisme aigu, non compliqué, Pf+ – 12,2 % avec AM dont 32 % de rechutes vraies

"Thaïlande, zone de multirésistances

32 "AL versus artésunate-méfloquine (AM) Présence de parasites à 28 j : Posologie plus élevée :

"200 patients (adultes et enfants) – 2,3 % avec AL ; 0 % avec AM 6 doses versus 4 précédemment

"Paludisme aigu, non compliqué, Pf+ Absence de génotypage des souches

"Thaïlande

33 "AL à diverses doses : Mesure de la médiane : Réapparition de parasites (période de 9 à 23 j) : Temps de clairance de la fièvre :

– A : 4 comprimés, 4 fois en 48 h ; – A : 40 h – A : 2 patients – A : 27,8 h

B : 2 comprimés, 4 fois en 48 h ; – B : 41 h – B : 4 patients – B : 32 h

C : 4 comprimés, 3 fois en 24 h – C : 39,5 h – C : 3 patients – C : 24,5 h

"Paludisme aigu, non compliqué, Pf+ Absence de génotypage des souches

"Thaïlande, 39 patients

34 "AL : deux schémas à 6 comprimés Pas de différence Réapparition de parasites à 28 j : Clairance de la fièvre :

et 1 à 4 comprimés entre les trois groupes 3,1 et 0,9 % pour les 6 comprimés ; pas de différence

"Paludisme aigu, non compliqué, Pf+ 16,4 % pour les 4 comprimés entre les trois groupes

"Thaïlande, 359 patients Absence de génotypage des souches

116

La Lettre de l’Infectiologue - Tome XVII - n° 4 - avril 2002

MISE AU POINT

valeur et les limites d’utilisation du Riamet®. Cette association,

contenant 20 mg d’artéméther et 120 mg de luméfantrine par

comprimé, réduit plus rapidement la parasitémie que la pyri-

méthamine-sulfadoxine (29), la méfloquine (30) ou l’halofan-

trine (31), et fait baisser la fièvre plus vite que la méfloquine

(30) ou l’halofantrine (31). En revanche, il n’y a pas de diffé-

rence notable par rapport à l’association artésunate-méfloquine

(26). Le suivi des patients pendant plusieurs semaines révèle

une plus grande fréquence de la réapparition de parasites chez

ceux traités par Riamet®que dans les autres cas (26, 29-32).

Les quelques expériences de génotypage qui ont pu être

réalisées montrent, en fait, que s’il y a de vraies rechutes, les

réapparitions de parasites sont, pour une large part, imputables

à une réinfection des sujets en raison d’une élimination relati-

vement rapide de la luméfantrine (26, 29). Une diminution de

la fréquence des rechutes est d’ailleurs observée lorsque les

doses sont augmentées (32-34). Le schéma consensuel optimal

correspond à la prise de 6 comprimés, répétée 4 fois en 48 h

(0, 8, 24 et 48eheure). Riamet®est proposé pour le traitement

des accès à P. falciparumrésistants aux autres médicaments sur

la base d’observations cliniques de son efficacité en Thaïlande,

où les souches plasmodiales sont connues pour être multi-

résistantes (26, 30, 32, 34), sans qu’il ait été démontré que les

patients impliqués dans les essais étaient porteurs de souches

résistantes. La présentation en comprimés réduit la prescrip-

tion aux formes non compliquées. Riamet®n’est pas proposé

en prophylaxie.

La neurotoxicité des dérivés de l’artémisinine (35, 36), d’une

part, et la crainte d’une cardiotoxicité de la luméfantrine en rai-

son de sa structure proche de celle de l’halofantrine, d’autre part,

ont conduit à rechercher spécifiquement ces paramètres dans plu-

sieurs études concernant l’innocuité de Riamet®. Des phéno-

mènes neurologiques anormaux (troubles de la démarche, pares-

thésies, tremblements, nystagmus, troubles de la coordination,

ataxie) ont été observés chez 3 % des 309 patients thaïlandais

traités, sans réaction neuropsychiatrique majeure, ni atteinte grave

du système nerveux central. Des vertiges ont été rapportés dans

15 % des cas et des troubles du sommeil dans 12 % des cas (26).

Globalement, les troubles observés n’apparaissent pas plus fré-

quents que ceux constatés chez des patients en pleine crise de

paludisme et traités par d’autres médicaments (26, 37). La fré-

quence des troubles ne semble pas augmentée entre les schémas

à 4 et 6 comprimés par prise (34). Par ailleurs, toutes les études

concordent pour affirmer une absence de cardiotoxicité de

l’association artéméther-luméfantrine (31, 37-39) [tableau II].

MALARONE®

Malarone®,initialement développé par GlaxoWellcome,

correspond à une association d’atovaquone et de proguanil.

L’atovaquone est une hydroxynaphtoquinone active sur Plas-

modium, mais également sur d’autres protistes (Pneumocystis,

Toxoplasma) (40). Elle inhibe le transport des électrons au

niveau mitochondrial en ciblant le complexe bc1du cytochrome

(41), elle diminue la biosynthèse des pyrimidines, car celle-ci

dépend du transport d’électrons via l’ubiquinone/ubiquinol

(42),et elle altère le potentiel de membrane au niveau des mito-

chondries (43). L’atovaquone agit sur les parasites en situation

intraérythrocytaire (44), y compris ceux résistants à d’autres

antimalariques (40, 45). Par ailleurs, il a été observé que l’ato-

vaquone était active sur les formes intrahépatiques de P. ber-

ghei et de P. falciparum (46), ce qui laissait entrevoir la possi-

bilité d’une utilisation de ce produit pour une prophylaxie

ciblant la première phase de développement du parasite chez

l’homme (prophylaxie “causale”).

Les essais expérimentaux sur animaux ont montré l’efficacité

de l’atovaquone sur des plasmodiums de rongeurs et sur

P. falciparum avec une absence de résistance croisée avec les

amino-4-quinoléines, les antifolates, la quinine et les amino-

alcools (40). Les premiers essais chez l’homme ont démontré

la rapidité d’action du produit, puisqu’une clairance parasitaire

et une nette régression des symptômes peuvent être obtenues

après la prise d’une dose unique de 500 mg. Toutefois, même

en augmentant les doses et la durée de prescription, un nombre

de rechutes important était observé (47). Il est maintenant éta-

bli que ce phénomène est imputable à l’apparition d’une résis-

tance du parasite à l’atovaquone (44), en relation avec des muta-

tions ponctuelles sur le gène du cytochrome b (48). Il était donc

évident que l’atovaquone ne pourrait être utilisée qu’en asso-

ciation.

Une série de tests réalisés in vitro ont montré que si l’atova-

quone et certains médicaments comme la méfloquine ou

l’artésunate pouvaient avoir un effet antagoniste, d’autres

associations révélaient un effet synergique, en particulier

avec le proguanil (49).

Le proguanil est un biguanide qui est métabolisé en un com-

posé particulièrement actif sur les parasites du genre Plasmo-

dium : le cycloguanil, un inhibiteur puissant de la dihydrofo-

late-réductase [DHFR] (50). Des mutations sur le gène de la

DHFR peuvent aboutir à une résistance des parasites au cyclo-

guanil (3, 4, 9) ; cependant, même dans ce cas, le proguanil

garde une activité antiparasitaire (51) suggérant que sa cible

d’action n’est pas limitée à la DHFR, mais pourrait également

impliquer un mécanisme de toxicité mitochondriale (52).

Le proguanil est actif non seulement sur les parasites en situa-

tion intraérythrocytaire, mais également sur le stade hépatique

et les gamétocytes (9, 46).

L’association atovaquone-proguanil a été testée à différentes

doses pour chacun des deux produits, ce qui a permis d’obser-

ver que les isolats de parasites, provenant de sujets présentant

une recrudescence de paludisme après traitement avec des doses

insuffisantes, n’étaient pas devenus systématiquement résis-

tants aux produits utilisés (44, 53).Aux doses retenues pour la

mise sur le marché de Malarone®(1 000 mg d’atovaquone et

400 mg de chlorhydrate de proguanil, 1 x/j, 3 jours de suite

chez l’adulte), l’efficacité thérapeutique globale est de plus

de 98 % chez des patients présentant des accès palustres non

compliqués à P. falciparum, infectés en Asie du Sud-Est, en

La Lettre de l’Infectiologue - Tome XVII - n° 4 - avril 2002

117

MISE AU POINT

Amérique du Sud ou en Afrique. Dans les groupes contrôles

correspondants, l’efficacité de la méfloquine était de 86 %, de

l’amodiaquine de 85 % et de la chloroquine de 8 à 30 %. Par

contre, une efficacité comparable a été obtenue avec la sulfa-

doxine-pyriméthamine, la quinine, la tétracycline ou l’halo-

fantrine. Chez les patients traités par atovaquone-proguanil et

pour lesquels une rechute a été observée 19 à 25 jours après le

début du traitement, il ne peut être exclu qu’un certain nombre

d’entre eux aient été réinfectés (53). Lorsque l’étude est menée

chez des sujets qui ne peuvent être réinfectés après traitement,

il est intéressant de constater qu’aucun phénomène de recru-

descence n’a été observé (54).

Quelques essais ont pu être réalisés chez des sujets infectés par

Plasmodium vivax. Malarone®s’est révélé efficace, mais,

treize fois sur dix-neuf, une rechute a été observée dans les

19 à 28 jours suivant le début du traitement. Les auteurs attri-

buent ces rechutes soit à la reviviscence de parasites intra-

hépatiques, soit à une véritable reprise de l’infection à partir de

formes intraérythrocytaires qui auraient persisté (53).Les essais

pratiqués chez des sujets infectés par Plasmodium ovale ou

Plasmodium malariaecomportent des effectifs trop faibles pour

être interprétables. Quant aux effets indésirables, ils ont été

observés avec une fréquence comparable dans les groupes

correspondants traités avec d’autres médicaments (53). Toute-

fois, des troubles gastro-intestinaux ont été plus fréquemment

rapportés que lors de l’utilisation de l’halofantrine chez des

sujets infectés ne résidant pas en zone d’endémie (54).

Malarone®peut également être utilisé pour la chimioprophy-

laxie du paludisme. De nombreuses études ont d’abord été réa-

lisées chez des sujets vivant en zone d’endémie où, sur un

ensemble de 600 participants, l’efficacité prophylactique avoi-

sinait les 98 % (55). Ces études ont été complétées d’observa-

tions effectuées chez des voyageurs se rendant occasionnelle-

ment en zone d’endémie, avec comme objectifs de confirmer

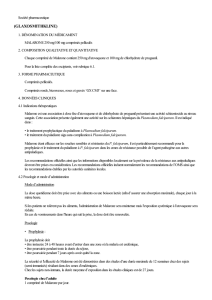

Tableau II. Principales caractéristiques de la présentation et des conditions d’utilisation de Riamet

®

et de Malarone

®

.

Paramètre Riamet

®

Malarone

®

Co-artem

®

(dans certains pays)

Traitement Traitement Prophylaxie

Composition 20 mg artéméther 250 mg atovaquone

par comprimé 120 mg luméfantrine 100 mg chlorhydrate de proguanil

Autorisation de mise Oui Oui Oui

sur le marché en France

Indication Accès palustre simple à P. falciparum(a) Accès palustre simple Prophylaxie du paludisme

Adulte et enfant à P. falciparum(a) à P. falciparum

Adulte et enfant de plus de 12 ans Valable pour les zones 2 et 3

(> 40 kg)(b) Sujets d’au moins 40 kg(c)

Posologie "Adulte : 4 comprimés/j, 3 j À prendre au cours d’un repas(e)

6 comprimés à 0, 8, 24, 48 h 1 comprimé/j : la veille du départ,

en zm+; 4 comprimés en zm-(d) tout le séjour et 7japrès le retour

"Enfant :

– 5-14 kg : 1 comprimé à 0, 8, 24, 36, 48, 60 h

en zm+,à 0,8, 24, 48 h en zm-

– 15-24 kg : 2 comprimés à 0, 8, 24, 36, 48, 60 h

en zm+,à 0,8, 24, 48 h en zm-

– 25-35 kg : 3 comprimés à 0, 8, 24, 36, 48, 60 h

en zm+,à 0,8, 24, 48 h en zm-

Contre-indication Hypersensibilité à l’un des composants Hypersensibilité à l’un des composants

Précautions d’emploi Aversion aux aliments, vomissements Diarrhée importante(f)

Risque de vertiges et de fatigue

Interactions Composés métabolisés par la CYP2D6 Rifampicine, métoclopramide(g),tétracycline :

(neuroleptiques, antidépresseurs tricycliques…) diminution significative des taux plasmatiques d’atovaquone

L’administration concomitante d’atovaquone et d’indinavir

entraîne une diminution de l’indinavir à des valeurs proches de la Cmin

Grossesse Pas d’effet malformatif Pas d’effet malformatif ou fœtotoxique connu

et allaitement ou fœtotoxique connu Prescription à évaluer en fonction du risque

Prescription à évaluer en fonction du risque Allaitement déconseillé pendant le traitement

Allaitement : absence de données

Effets Troubles du sommeil, céphalées, étourdissements, Vomissements, nausées, diarrhée, douleurs abdominales, céphalées

indésirables palpitations, douleurs abdominales, anorexie, Anomalies réversibles du bilan hépatique

vomissements, nausées, diarrhée, prurit,

éruption cutanée, toux, arthralgies, myalgies, asthénie

(a) Le bénéfice n’a pas été établi dans le traitement de l’accès pernicieux, grave ou compliqué . (b) En raison de l’absence de données chez l’enfant de moins de 12 ans.

(c) Les études chez les enfants sont actuellement en cours. (d) zm+: zone de multirésistance, zm-: zone sans multirésistance. (e) Amélioration sensible de l’absorption.

(f) Une étude récente montre cependant que la diarrhée n’affecte pas l’efficacité du médicament (58). (g) Malarone®reste cependant efficace dans 98 % des cas (53).

118

La Lettre de l’Infectiologue - Tome XVII - n° 4 - avril 2002

MISE AU POINT

l’efficacité du médicament dans des populations non immunes,

mais surtout d’évaluer la compliance (56, 57). En effet, il est

bien connu que tout événement indésirable que le voyageur/tou-

riste impute à la prise d’une prophylaxie aboutit le plus sou-

vent à une suspension de celle-ci, et donc à un risque accru de

contracter un paludisme. Dans les deux études menées sur un

total de plus de 2 000 voyageurs, la tolérance de l’association

atovaquone-proguanil a été supérieure à celle de la méfloquine

(57) ou de l’association chloroquine-proguanil (56), avec une

efficacité de 100 %. Par ailleurs, l’activité “causale” de Mala-

rone®permet de suspendre la prise du produit 7 jours après avoir

quitté la zone d’endémie (et non 3 ou 4 semaines, comme dans

les autres chimioprophylaxies) [tableau II].

CONCLUSION

La diminution de l’efficacité des antipaludéens actuellement

disponibles et l’absence de perspectives vaccinales concrètes

dans un avenir immédiat incitent à privilégier la recherche de

nouveaux médicaments. Découvrir de nouveaux antipaludéens

est une priorité sanitaire mondiale affichée par de nombreux

organismes, et des efforts significatifs y ont été consacrés au

cours de ces dernières années. Riamet®et Malarone®sont deux

nouvelles associations commercialisées sous une même forme

galénique, répondant à cette demande. En effet, Riamet®et

Malarone®se présentent dans des formulations orales et sont

indiquées dans le traitement curatif des accès palustres simples

dus à des souches de P. falciparum résistantes aux autres anti-

paludiques. Tandis que l’utilisation de Riamet® est réservée au

traitement curatif, Malarone®peut également être prescrit en

chimioprophylaxie. Son activité reconnue contre les souches

multirésistantes rend Malarone®utilisable par les voyageurs

séjournant aussi bien en zone 2 qu’en zone 3, ce qui devrait

faciliter le travail du prescripteur. Par ailleurs, la durée du trai-

tement, limitée à 7 jours après le retour, rend cette présentation

attractive et devrait permettre d’améliorer la compliance.#

RÉFÉRENCES BIBLIOGRAPHIQUES

1. Wellems TE, Su X, Ferdig M, Fidock DA. Genome projects, genetic analysis,

and the changing landscape of malaria research. Curr Opin Microbiol 1999 ; 2 :

415-9.

2. Camus D, Slomianny C, Savel J. Biologie de Plasmodium. In : Elsevier (ed.).

Encycl Med Chir Maladies Infectieuses 1997 ; 8-507-A-10, 7 p.

3. Sirawaraporn W, Yongkiettrakul S, Sirawaraporn R, Yuthavong Y. Santi DV.

Plasmodium falciparum : asparagine mutant at residue 108 of dihydrofolate

reductase is an optimal anti-folate resistant mutant. Exp Parasitol 1997 ; 87 :

245-52.

4. Macreadie I, Ginsburg H, Sirawaraporn W, Tilley L. Antimalarial drug deve-

lopment and new targets. Parasitol Today 2000 ; 16 : 438-44.

5. Chaiyaroj SC, Buranakiti A, Angkasekwinai P, Looareesuwan S, Cowman AF.

Analysis of mefloquine resistance and amplification of pfmdr1 in multidrug-resis-

tant Plasmodium falciparum isolates from Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999 ;

61 : 780-3.

6. Peel SA, Bright P, Yount B, Handy J, Baric RS. A strong association between

mefloquine and halofantrine resistance and amplification, overexpression, and

mutation in the P-glycoprotein gene homolg (pfmdr) of Plasmodium falciparum.

Am Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994 ; 51 : 648-58.

7. Ancelin ML, Vial HL. Quaternary ammonium compounds efficiently inhibit

Plasmodium falciparum growth in vivo by impairment of choline transport.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1986 ; 29 : 814-20.

8. Bécuwe P, Gratepanche S, Fourmaux MN et al. Characterization of an iron-

dependent endogenous superoxide dismutase of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol

Biochem Parasitol 1996 ; 76 : 125-34.

9. Olliaro PL, Yuthavong Y. An overview of chemotherapeutic targets for anti-

malarial drug discovery. Pharmacol Ther 1999 ; 81 : 91-110.

10. Delhaes L, Abessolo H, Biot C et al. In vitro and in vivo antimalarial acti-

vity of ferrochloroquine, a ferrocenyl analog of chloroquine against chloroquine-

resistant malaria parasites. Parasitol Res 2001 ; 87 : 239-44.

11. Dhingra V, Vishweshwar Rao K, Lakshmi Narasu M. Current status of arte-

misinin and its derivatives as antimalarial drugs. Life Sci 2000 ; 66 : 279-300.

12. Olliaro PL, Haynes RK, Meunier B, Yuthavong Y. Possible mode of action of

artemisinin-type compounds. Trends Parasitol 2001 ; 17 : 122-6.

13. White NJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of artemisinin

and derivatives. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994 ; 88 (suppl.) : 41-3.

14. Ambroise-Thomas P. L’artéméther intramusculaire dans le traitement des

paludismes graves : synthèse des résultats actuels. Med Trop 1997 ; 57 : 289-93.

15. Karbwang J, Na-BangChang K, Congpuong K et al. Pharmacokinetics and

bioavailability of oral and intramuscular artemether. Eur J Clin Pharmacol

1997 ; 52 : 307-10.

16. Ezzet F, Mull R, Karbwang J. The population pharmacokinetics

of CGP 56697 and its effects on the therapeutic response in malaria patients.

Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998 ; 46 : 553-61.

17. World Health Organisation. Severe and complicated malaria. Trans R Soc

Trop Med Hyg 1990 ; 84 (suppl. 2) : 1-65.

18. Marsh K, Forster D, Waruiri C et al. Indicators of live-threatening malaria

in African children. N Engl J Med 1995 ; 332 : 1399-404.

19. Jelinek T, Schelbert P, Loescher T, Eichenlaub D. Quinine resistant falcipa-

rum malaria acquired in East Africa. Trop Med Parasitol 1995 ; 46 : 38-40.

20. Molinier S, Imbert P, Verrot D, Morillon M, Parzy D, Touze JE. Paludisme à

Plasmodium falciparum : résistance de type RI à la quinine en Afrique de l’Est.

Presse Med 1994 ; 23 : 1494.

21. Kondrachine AV, Trigg PI. Global overview of malaria. Indian J Med Res

1997 ; 106 : 39-52.

22. World Health Organisation. The role of artemisinin and its derivatives in the

current treatment of malaria. Document WHO/MAL 1993 ; 94 : 1067.

23. Looareesuwan S. Overview of clinical studies on artemisinin derivatives in

Thailand. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994 ; 88 (suppl.) : 9-11.

24. Hassan Alin M, Bjorkman A, Wensdorfer WH. Synergism of benflumetol and

artemether in Plasmodium falciparum. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999 ; 61 : 439-45.

25. Xiuquing J, Guang-Yu L, Cheng-Qi S et al. Phase II trial in China of a new,

rapidly acting and effective oral malarial CGP 56697, for the treatment of

Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health

1997 ; 28 : 476-81.

26. Van Vugt M, Brockman A, Gemperli B et al. Randomized comparison of arte-

mether-benflumetol and artesunate-mefloquine in treatment of multidrug resistant

falciparum malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998 ; 42 : 135-9.

27. Hatz C, Abdulla S, Mull D et al. Efficacy and safety of CGP 56697 (arte-

mether and benflumetol) compared with chloroquine to treat acute malaria in

Tanzanian children aged 1-5 years. Trop Med Int Health 1998 ; 3 : 498-504.

28. Von Seidlein L, Jaffar S, Pinder M et al. Treatment of African children with

uncomplicated falciparum malaria with a new antimalarial drug CGP 56697.

J Infect Dis 1997 ; 176 : 1113-6.

29. Von Seidlein L, Bojang K, Jones P et al. A randomized controlled trial of

artemether/benflumetol, a new antimalarial and pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine in

the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in African children. Am J Trop

Med Hyg 1998 ; 58 : 638-44.

30. Looareesuwan S, Wilairatana P, Chokejindachai W et al. A randomized,

double-blind, comparative trial of a new combination of artemether and benflu-

metol (CGP 56697) with mefloquine in the treatment of acute Plasmodium falci-

parum malaria in Thailand. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999 ; 60 : 238-43.

6

6

1

/

6

100%