Crises d`épilepsie chez les patients transplantés cardiaques

doi: 10.1684/epi.2010.0316

Crises d’épilepsie

chez les patients

transplantés cardiaques

Vincent Navarro

1

, Shaida Varnous

2

, Damien Galanaud

3

, Elisabeth Vaissier

2

,

Iradj Gandjbakhch

2

, Michel Baulac

1

1

Unité d’épilepsie et département de neurophysiologie clinique, pôle des maladies du système nerveux,

hôpital de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, 47-83 boulevard de l’Hôpital, 75013 Paris, France

2

Service de chirurgie cardiaque, hôpital de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France

3

Service de neuroradiologie, hôpital de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, Paris, France

Résumé. Des complications neurologiques de sévérité variable émaillent fréquemment les transplantations

cardiaques. Elles peuvent être liées à une neurotoxicité directe des immunosuppresseurs, des complications infec-

tieuses ou tumorales des immunosuppresseurs ou des accidents vasculaires cérébraux (AVC). Ces complications

sont souvent à l’origine de crises d’épilepsie. L’incidence des crises oscille entre 1,6 et 17 % des patients adultes

greffés cardiaques. Un syndrome d’encéphalopathie postérieure réversible lié à la cyclosporine et un AVC sont les

deux principales causes de crises précoces, survenant dans les semaines suivant la transplantation. Un bilan étio-

logique doit être systématiquement réalisé, incluant rapidement une IRM cérébrale, car différentes complications

peuvent s’associer. La prise en charge repose non seulement sur un traitement symptomatique des crises, mais

aussi sur la correction précoce des facteurs étiologiques.

Mots clés :crise d’épilepsie,transplantation,cyclosporine,encéphalopathie postérieure réversible,maladies cérébrovasculaires

Abstract. Epileptic seizures in patients after heart transplantation

Neurological complications with various severity frequently occur after heart transplantation. They can be due to the

direct neuro-toxicity of immunosuppressive drugs, or to the infectious or tumor complications of immunosuppressive

drugs, or to strokes. These complications are often at the origin of seizures. Incidence of seizures varies from 1.6 to 17%

of the adult patients after heart transplantation. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome due to cyclosporine

treatment and strokes are the two main causes of early seizures occurring in the weeks after heart transplantation.

A systematic screening of the factors for seizures must be performed, including a brain MRI, because several

complications can be associated. Control of the seizures relies not only on symptomatic treatment of the seizures,

but also by identifying and correcting the aetiological factors.

Key words:seizure,transplantation,cyclosporine,posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome,cerebrovascular disease

Des complications neurologiques survien-

nent dans 30 à 80 % des transplantations

d’organe (Patchell, 1994). Leur fréquence

dépend de la durée de suivi après une transplan-

tation cardiaque, oscillant entre 23 % en péri-

opératoire et 81 % après 18 ans de suivi (van

de Beek et al., 2008). Il peut s’agir de complica-

tions communes aux transplantations d’organe :

–toxicité directe des immunosuppresseurs ;

–complications infectieuses ou tumorales

des immunosuppresseurs (Patchell, 1994 ;

Senzolo et al., 2009).

Il peut aussi s’agir de complications propres

à la transplantation cardiaque, principalement

d’origine cérébrovasculaire (Malheiros et al.,

2002 ; Cemillan et al., 2004 ; Zierer et al.,

Épilepsie et cœur

Épilepsie et cœur

Épilepsies 2010 ; 22 (3) : 207-11

Tirés à part :

V. Navarro

Épilepsies, vol. 22, n° 3, juillet-août-septembre 2010

207

Copyright © 2017 John Libbey Eurotext. Téléchargé par un robot venant de 88.99.165.207 le 03/06/2017.

2007). La proportion de l’ensemble de ces complications

neurologiques dépend de la pathologie cardiaque sous-jacente

(Malheiros et al., 2002).

Les complications neurologiques peuvent être transitoires

ou de faible intensité (par exemple, le tremblement fréquem-

ment observé chez les patients traités par cyclosporine), mais

peuvent aussi être irréversibles et sévères (Senzolo et al.,

2009). Ces dernières sont d’ailleurs un des plus importants

facteurs influençant la qualité de vie des patients transplantés.

Comme les crises peuvent être le symptôme révélateur

d’une complication neurologique, il est indispensable d’en

rechercher la cause et de ne pas se limiter à un seul traitement

symptomatique des crises.

Incidence des crises

chez les patients transplantés cardiaques

Selon les études, l’incidence des crises chez les patients

ayant reçu une greffe cardiaque est variable : de 1,6 %

(Perez-Miralles et al., 2005) à 17 % (Malheiros et al., 2002)

chez l’adulte et de 21 à 26 % chez l’enfant (Martin et al.,

1992 ; Raja et al., 2003).

Dans une étude récente, portant sur la population de

patients adultes transplantés cardiaques durant une période

de trois ans dans le service de chirurgie cardiaque de l’hôpital

de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, à Paris, nous avons identifié huit

patients, parmi les 166 patients greffés, qui avaient présenté

des crises d’épilepsie, soit une incidence de 4,6 % (Navarro

et al., 2010). Ce pourcentage n’est pas statistiquement différent

de celui constaté dans le même service 20 ans auparavant : 6 %

d’une cohorte de 129 greffés (Baulac et al., 1989). Cette absence

de différence significative, en dépit d’améliorations de la prise

en charge médicale (meilleure équilibration de la posologie de

la cyclosporine, adaptée à des dosages sanguins quotidiens

durant les premiers jours après la transplantation) et chirurgi-

cale (évitant notamment les crises précoces secondaires à une

embolie gazeuse), pourrait être liée au fait qu’une transplanta-

tion cardiaque est proposée aujourd’hui à des patients parfois

plus fragiles.

Facteurs de risque de crises

chez les patients transplantés cardiaques

Encéphalopathie postérieure réversible liée

aux anticalcineurines (EPRA)

Dans la moitié des cas de notre étude (Navarro et al., 2010),

soit 2,4 % des patients greffés, les crises étaient liées à

une EPRA. Ce syndrome clinicoradiologique peut également

se rencontrer lors d’encéphalopathie hypertensive, comme

l’hypertension artérielle maligne, l’éclampsie ou la prise

d’érythropoïétine. D’après une revue de la littérature portant

sur 50 cas, les EPRA se manifestent : par des troubles visuels

liés à une atteinte des lobes occipitaux (cécité corticale,

hallucinations visuelles) dans plus d’un quart des cas ; par des

céphalées, des troubles de la vigilance ou une confusion dans

la moitié des cas ; et par des crises d’épilepsie dans près de trois

quarts des cas (Singh et al., 2000). Sur un scanner cérébral, des

hypodensités peuvent parfois être détectées dans les régions

postérieures. Mais c’est sur l’IRM cérébrale que ces anomalies

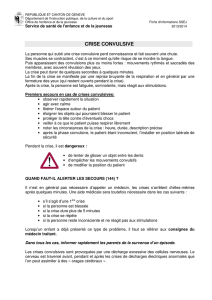

sont les plus évidentes (figure 1).Ils’agit alors d’hypersignaux de

Suivi

D

C

F

E

B

A

Initiale

Figure 1. Encéphalopathie postérieure réversible à la cyclosporine,

A-D. L’IRM cérébrale (A, B : séquence de diffusion ; C, D : séquence

FLAIR) d’une patiente, âgée de 17 ans, ayant présenté des crises

d’épilepsie six jours après une transplantation cardiaque a révélé

d’importants hypersignaux de la substance blanche, mais égale-

ment du cortex prédominant dans les régions postérieures ainsi

qu’au niveau du vertex. E, F. L’IRM de contrôle (séquence FLAIR),

réalisée 39 jours plus tard, montre une nette régression de ces

anomalies.

V. Navarro, et al.

Épilepsies, vol. 22, n° 3, juillet-août-septembre 2010 208

Copyright © 2017 John Libbey Eurotext. Téléchargé par un robot venant de 88.99.165.207 le 03/06/2017.

la substance blanche, mais également du cortex, dans les séquen-

ces pondérées en T2 et en FLAIR, apparaissant parfois en hypo-

signal dans les séquences pondérées T1. Ces anomalies ont une

localisation cérébrale très évocatrice, prédominant dans les

régions postérieures (maximum à la jonction pariétooccipitale),

mais pouvant également s’étendre vers l’avant dans les formes

plus sévères. Les séquences en diffusion permettent également

de préciser qu’il s’agit plutôt d’un œdème vasogénique (iso-

intensité) que d’un œdème cytotoxique (hyperintensité). L’IRM

cérébrale permet, de plus, d’identifier d’autres types de complica-

tions (ischémie cérébrale récente, lésion infectieuse, etc.).

La physiopathologie de l’EPRA est mal connue et résulte

probablement d’une toxicité des cellules endothéliales cérébrales

(Fogo, 2000), qui pourrait être médiée par une forte élévation

du taux d’endothéline (Haug et al., 1995). Cette protéine a

un puissant effet vasoconstricteur et pourrait ainsi perturber

les échanges au travers de la barrière hématoencéphalique.

La sensibilité accrue des régions cérébrales postérieures est vrai-

semblablement liée à la moindre innervation sympathique des

vaisseaux dans ce territoire (Beausang-Linder et Bill, 1981).

De plus, une hypertension artérielle systémique induite par la

cyclosporine pourrait être un facteur aggravant. Outre des taux

suprathérapeutiques d’anticalcineurines, d’autres facteurs favo-

risant la survenue d’une EPRA ont été rapportés, comme une

hypomagnésémie, une insuffisance rénale, une hypocholestéro-

lémie ou une corticothérapie à forte dose (Hinchey et al., 1996).

Parfois, aucun de ces facteurs n’est retrouvé, comme ce fut le cas

pour nos quatre patients ayant présenté une EPRA.

L’EPRA survient indépendamment de la pathologie sous-

jacente. C’est pourquoi elle est décrite aussi bien après une

transplantation cardiaque (Martin et al., 1992) qu’une transplan-

tation rénale (McCormick et al., 1976), hépatique (Singh et al.,

2000) ou de moelle osseuse (Teive et al., 2001). La fréquence

des EPRA (2,4 %), dans notre série (Navarro et al., 2010), est pro-

che de celle (1,6 %) rapportée chez des greffés de moelle (Wong

et al., 2003). Lorsqu’elle est identifiée précocement et qu’une

adaptation du traitement immunosuppresseur est réalisée

(cf. infra), l’EPRA est totalement réversible. Parfois, lorsque les

lésions initiales ont été très importantes, des séquelles ischémi-

ques peuvent persister sur les IRM cérébrales de contrôle.

Même si davantage de cas d’EPRA liée à la prise de cyclo-

sporine ont été rapportés, le FK 506 expose au même risque

(Freise et al., 1991 ; Wong et al., 2003).

Complications neurovasculaires

La deuxième principale cause de crise d’épilepsie est la

survenue d’un accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) durant

la période périopératoire (Sila, 1989 ; Pless et Zivkovic, 2002).

Dans notre série, cinq patients sur huit ont présenté ce type

de complications. L’AVC est le plus souvent révélé par des

crises. Il s’agit :

–soit d’un AVC ischémique dans des territoires vasculaires

jonctionnels lié à un bas débit sanguin cérébral avant la greffe,

du fait de la pathologie cardiaque sous-jacente, ou durant la

greffe, du fait de difficultés chirurgicales et/ou réanimatoires ;

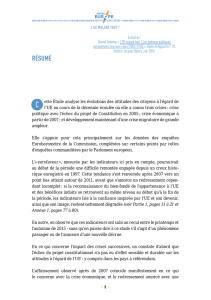

–soit d’un AVC ischémique cardioembolique, qui a la particu-

larité d’être souvent secondairement hémorragique (figure 2) ;

–soit d’un AVC ischémique par thrombose artérielle, chez des

patients ayant une athérosclérose diffuse sous-jacente ;

–soit enfin d’un AVC hémorragique lié à l’anticoagulation.

Autres facteurs de risque de crises

D’autres facteurs de risque de crises sont à évoquer systé-

matiquement. Des anomalies métaboliques proépileptogènes

peuvent survenir dans les premiers jours après la greffe mais

sont faciles à éviter. Des infections du système nerveux peu-

vent se révéler par des crises d’épilepsie. Il s’agit alors d’infec-

tions opportunistes qui surviennent tardivement après la greffe

(en général après six mois), notamment chez les patients ayant

un traitement immunosuppresseur renforcé du fait d’un rejet.

Des lymphomes cérébraux associés à l’EBV (Weintraub et

Warnke, 1982) peuvent également se révéler par des crises.

La pathologie sous-jacente motivant la transplantation car-

diaque peut aussi contribuer à la survenue de crises. C’est

notamment le cas des patients ayant une maladie mitochon-

driale, responsable d’une cardiomyopathie, mais aussi d’une

atteinte du système nerveux central associée à une épilepsie.

Enfin, il convient systématiquement de rechercher l’asso-

ciation de plusieurs facteurs de risque aux crises des patients

transplantés. Deux des huit patients de notre série avaient

trois facteurs identifiés (figure 2).

Caractéristiques des crises d’épilepsie

chez les patients transplantés

Les crises sont habituellement associées à d’autres signes

neurologiques, mais lorsqu’elles sont généralisées, ce qui est le

cas chez la plupart des patients, elles sont le symptôme le plus

visible chez des patients hospitalisés dans une réanimation

postchirurgicale. A posteriori, un début focal est souvent

retrouvé. Une sémiologie visuelle initiale (déficit du champ

visuel, hallucinations) oriente vers une EPRA tout comme vers

un AVC dans un territoire postérieur.

Le délai de survenue des crises dépend de leur étiologie.

Dans les EPRA et les AVC periopératoires, les crises surviennent

précocement après l’intervention, avec un délai moyen de huit

jours dans notre série. Les crises survenant plusieurs mois après

l’intervention doivent plutôt faire rechercher des complica-

tions infectieuses ou tumorales.

Les crises sont habituellement faciles à contrôler si une

prise en charge étiologique est menée en parallèle (Chabolla

et Wszolek, 2006). Dans notre série, la mortalité était identique

parmi les patients ayant présenté des crises et ceux n’en ayant

pas présenté. Chez les patients ayant présenté des crises, la

mortalité n’était pas liée aux crises, mais à des complications

infectieuses ou tumorales liées aux immunosuppresseurs, ou à

Crises après transplantation cardiaque

Épilepsies, vol. 22, n° 3, juillet-août-septembre 2010

209

Copyright © 2017 John Libbey Eurotext. Téléchargé par un robot venant de 88.99.165.207 le 03/06/2017.

Initiale

Suivi

AB

CD E

FGH

Figure 2. Association de trois lésions cérébrales favorisant la survenue de crises. A-E. L’IRM cérébrale (A : séquence T2* ; B : séquence de

diffusion, C-E : séquence FLAIR) d’une patiente, âgée de 42 ans, ayant présenté des crises d’épilepsie 16 jours après une transplantation

cardiaque a révélé : 1) la cicatrice d’un ancien AVC ischémique sylvien gauche (image C), 2) un AVC secondairement hémorragique récent

frontal droit (images A et B) et 3) une encéphalopathie postérieure à la cyclosporine (images C-E) ; F, G. L’IRM de contrôle (séquence FLAIR)

réalisée 34 jours plus tard montre la persistance de la cicatrice sylvienne gauche, la diminution de volume de l’AVC hémorragique frontal

droit et la disparition de l’encéphalopathie postérieure à la cyclosporine.

V. Navarro, et al.

Épilepsies, vol. 22, n° 3, juillet-août-septembre 2010 210

Copyright © 2017 John Libbey Eurotext. Téléchargé par un robot venant de 88.99.165.207 le 03/06/2017.

un déficit neurologique post-AVC. Les AVC périopératoires ont

en effet été identifiés comme la complication neurologique

affectant le plus la survie des patients (van de Beek et al., 2008).

Prise en charge de crises d’épilepsie

chez un patient transplanté

Cette prise en charge repose sur un bilan étiologique, un

traitement étiologique et un traitement symptomatique.

Bilan étiologique

Un bilan étiologique, comportant un scanner cérébral en

urgence, puis une IRM cérébrale (comportant notamment des

séquences FLAIR et de diffusion) dès que possible, un EEG au

lit du patient, un bilan sanguin avec un dosage de l’anticalci-

neurine, est indispensable. Ce bilan doit être réalisé, même si le

patient a des antécédents connus d’épilepsie. En fonction de ce

bilan initial, d’autres examens peuvent être nécessaires (bilan

cardiovasculaire, bilan infectieux, etc.).

Un traitement étiologique

Dans le cas de l’EPRA, si un surdosage de l’anticalcineurine

a été identifié, une baisse de la posologie de cette dernière,

selon certains auteurs (Singh et al., 2000), peut suffire. Si

aucun surdosage n’a été détecté, le changement pour une

autre anticalcineurine peut être proposé (passage au

tacrolimus-FK 506 si le patient était sous cyclosporine ou

l’inverse). Il est aussi envisageable de passer à une autre classe

de molécules immunosuppressives, comme les inhibiteurs de

TOR (la rapamycine). Une correction des facteurs favorisants

l’EPRA doit également être réalisée (apport de magnésium,

contrôle d’une hypertension artérielle).

Traitement symptomatique

Un traitement symptomatique, comportant initialement

une molécule antiépileptique d’action rapide, comme une

benzodiazépine (par exemple clonazépam 1 mg toutes les six

à huit heures), en perfusion intraveineuse discontinue, puis

en fonction du nombre de crises, de l’existence ou non d’une

lésion cérébrale sous-jacente, un traitement antiépileptique de

fond peut être instauré, en privilégiant les antiépileptiques de

nouvelle génération qui ne sont ni inducteurs ni inhibiteurs

enzymatiques.

□

Conflit d’intérêt : aucun.

Références

Baulac M, Smadja D, Cabrol A, Cabrol C, LaPlane D. Cyclosporin and

convulsions after cardiac transplantation. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1989 ; 145 :

393-7.

Beausang-Linder M, Bill A. Cerebral circulation in acute arterial

hypertension: protective effects of sympathetic nervous activity.

Acta Physiol Scand 1981 ; 111 : 193-9.

Cemillan CA, Alonso-Pulpon L, Burgos-Lazaro R, Millan-Hernandez I,

del Ser T, Liano-Martinez H. Neurological complications in a series of 205

orthotopic heart transplant patients. Rev Neurol 2004 ; 38 : 906-12.

Chabolla DR, Wszolek ZK. Pharmacologic management of seizures in

organ transplant. Neurology 2006 ; 67 : S34-8.

Fogo A. Cyclosporine toxicity. Am J Kidney Dis 2000 ; 36 : E1.

Freise CE, Rowley H, Lake J, Hebert M, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Similar

clinical presentation of neurotoxicity following FK 506 and cyclosporine

in a liver transplant recipient. Transplant Proc 1991 ; 23 : 3173-4.

Haug C, Duell T, Lenich A, Kolb HJ, Grunert A. Elevated plasma

endothelin concentrations in cyclosporine-treated patients after bone

marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 1995 ; 16 : 191-4.

Hinchey J, Chaves C, Appignani B, et al. A reversible posterior

leukoencephalopathy syndrome. N Engl J Med 1996 ; 334 : 494-500.

Malheiros SM, Almeida DR, Massaro AR, et al. Neurologic complica-

tions after heart transplantation. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2002 ; 60 : 192-7.

Martin AB, Bricker JT, Fishman M, et al. Neurologic complications of

heart transplantation in children. J Heart Lung Transplant 1992 ; 11 :

933-42.

McCormick WF, Schochet Jr SS, Sarles HE, Calverley JR. Progressive

multifocal leukoencephalopathy in renal transplant recipients. Arch Intern

Med 1976 ; 136 : 829-34.

Navarro V, Varnous S, Galanaud D, et al. Incidence and risk factors

for seizures after heart transplantation. J Neurol 2010 ; 257 : 563-8.

Patchell RA. Neurological complications of organ transplantation.

Ann Neurol 1994 ; 36 : 688-703.

Perez-Miralles F, Sanchez-Manso JC, Almenar-Bonet L, Sevilla-

Mantecon T, Martinez-Dolz L, Vilchez-Padilla JJ. Incidence of and risk fac-

tors for neurologic complications after heart transplantation. Transplant

Proc 2005 ; 37 : 4067-70.

Pless M, Zivkovic SA. Neurologic complications of transplantation.

Neurologist 2002 ; 8 : 107-20.

Raja R, Johnston JK, Fitts JA, Bailey LL, Chinnock RE, Ashwal S. Post-

transplant seizures in infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Pediatr Neurol 2003 ; 28 : 370-8.

Senzolo M, Ferronato C, Burra P. Neurologic complications after solid

organ transplantation. Transpl Int 2009 ; 22 : 269-78.

Sila CA. Spectrum of neurologic events following cardiac transplanta-

tion. Stroke 1989 ; 20 : 1586-9.

Singh N, Bonham A, Fukui M. Immunosuppressive-associated

leukoencephalopathy in organ transplant recipients. Transplantation

2000 ; 69 : 467-72.

Teive HA, Brandi IV, Camargo CH, et al. Reversible posterior leucoen-

cephalopathy syndrome associated with bone marrow transplantation.

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2001 ; 59 : 784-9.

van de Beek D, Kremers W, Daly RC, et al. Effect of neurologic

complications on outcome after heart transplant. Arch Neurol 2008 ; 65 :

226-31.

Weintraub J, Warnke RA. Lymphoma in cardiac allotransplant reci-

pients. Clinical and histological features and immunological phenotype.

Transplantation 1982 ; 33 : 347-51.

Wong R, Beguelin GZ, de Lima M, et al. Tacrolimus-associated poste-

rior reversible encephalopathy syndrome after allogeneic haematopoietic

stem cell transplantation. Br J Haematol 2003 ; 122 : 128-34.

Zierer A, Melby SJ, Voeller RK, et al. Significance of neurologic

complications in the modern era of cardiac transplantation. Ann Thorac

Surg 2007 ; 83 : 1684-90.

Crises après transplantation cardiaque

Épilepsies, vol. 22, n° 3, juillet-août-septembre 2010

211

Copyright © 2017 John Libbey Eurotext. Téléchargé par un robot venant de 88.99.165.207 le 03/06/2017.

1

/

5

100%