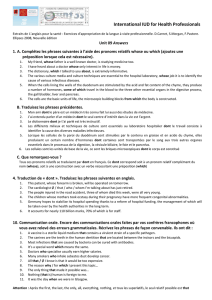

Colloque international « Les émotions dans la psychologie de la forme

Colloque international

« Les émotions dans la psychologie de la forme »

Organisé par les Archives Husserl de Paris (UMR 8547 « Pays germaniques »)

dans le cadre du Projet

ANR « Emphiline » coordonné par Natalie Depraz

le samedi 24 janvier à l'ENS rue d'Ulm, salle Celan.

Organisé par Eric Trémault, Natalie Depraz et Charles-Edouard Niveleau

Matinée : Présidence : Dominique Pradelle

9h30 : Introduction

10h00 : Guillaume Fréchette (Universités de Salzbourg et Genève) : Objet vs

unité. Deux conceptions gestaltistes de l’émotion.

11h00 : Denis Seron(Université de Liège) : Analyser l’émotion (12h00-

14h30 :Pause déjeuner) Après-midi : Présidence : Natalie Depraz

14h30 : Victor Rosenthal (EHESS) : La non neutralité de l’expérience :

quelques remarques sur les qualités expressives et le monde interhumain des

mouvances gestaltistesde l’Allemagne des années 1920-1930.

15h30 : Clelia Zernik (Beaux-arts de Paris) : Tension et suspense chez

Rudolf Arnheim: à partir de quelques exemples d'émotions esthétiques.

(Pause : 15 mns)

16h30 : Johan Wagemans (KU Leuven) : Emotional responses to art works

Argument Bien que cela ait encore été trop peu remarqué, letraitement des

émotions joue dans la psychologie de la forme de Berlin un rôlestratégique

tout à fait central : en effet, Köhler et Koffka voient enelles le lieu par

excellence où se réalise leur hypothèse de

l’isomorphismepsychophysiologique. En effet, les émotions sont conçues

comme des« qualités de forme » dynamiques manifestant phénoménalement

lesrelations causales, dans le cerveau, entre les corrélats physiologiques

del’environnement et du corps propre perçus. Dès lors, elles sont le

phénomène oùl’hypothèse même d’une « organisation manifeste », qui rend

possiblela thèse de l’isomorphisme psychophysique, peut être étudiée

directement.Au-delà de l’hypothèse consistant à trouver ainsi dans

lesémotions un corrélat phénoménal aux structures causales du cerveau,

cetteapproche des émotions a pour spécificité de les traiter comme des

relations,quoique d’un ca

ractère spécial, puisque phénoménalement manifestes et dotées àcet égard

d’un caractère « dynamique », en lequel est censé semanifester précisément

la causalité sous-jacente. Or cette approche enelle-même possède de

nombreux avantages, qui font qu’elle mérite déjà qu’on s’yattarde. Si les

émotions sont en effet des relations (ou structures) causalesdirectement

senties entre les figures de l’environnement et celle du corpspropre, alors

on rend simultanément compte, à la fois des « caractèresexpressifs » ou

« physionomiques » (effrayant, apaisant,fascinant, etc., et même « beau »)

avec lesquels apparaissent lesobjets environnants, et des « tendances à

l’action » dont lesémotions semblent indissociables pour le sujet qui les

éprouve : cescaractères et tendances sont alors des prédicats relationnels,

c'est-à-diredeux manières, l’une subjective et l’autre objective, de parler

de la mêmeréalité phénoménale, à

savoir la relation causale éprouvée elle-même entrele sujet et l’objet.

Par là, ce traitement des émotions possède une féconditéindépendante de

l’hypothèse de l’isomorphisme, fécondité dont s’est notammentemparé Kurt

Lewin en proposant une phénoménologie de la structuration dynamiqueet

émotionnelle du champ sensible détachée de toute hypothèse naturalistesous-

jacente. Dans ses cours à la Sorbonne, c’est dans les traces de Lewin

queMerleau-Ponty s’inscrit explicitement, en rejetant le naturalisme de

l’école deBerlin tout en marquant fortement l’intérêt de cette approche

structurale desémotions et des phénomènes expressifs, qui le guide dès La

structure ducomportement.Mais c’est également le statut fondamental que

Koffka accordeà la structuration émotionnelle du monde perçu qui marquera

fortement denombreux philosophes (Cassirer, Scheler, Merleau-Ponty) et

psychologues(Werner, Buijtendjik, Tolman, Gibson) : en s’appuyant sur

la psychologiede l’enfant naissante, Koffka émet l’hypothèse selon

laquelle les émotionsainsi conçues seraient le rapport perceptif primitif

des organismes vivants aumonde, qui se manifesterait alors précisément

comme originairement« expressif », plutôt que comme un ensemble de qualités

substantiellesqui répondraient davantage à une interrogation attentive

d’ordre intellectuel.L’expressivité émotionnelle serait alors comme une

couche biologique primitivede l’intentionnalité perceptive, à partir de

laquelle on pourrait espérerrendre compte généalogiquement de la perception

et de la consciencespécifiquement humaines.L’une des questions centrales

est alors de savoir si l’onpeut vraiment faire de la perception expressive

un rapport immédiat au monde (àpartir duquel on pourrait éventuellement

chercher, comme Merleau-Ponty, àdériver jusqu’à notre perception des

qualités sensibles), ou s’il ne faut pas,au contraire, nécessairement fon

der ce rapport sur une facticité purementqualitative, qui ne prendrait des

valeurs émotionnelles que dans l’appréhensionde son rapport à nos

fins. Though it has been too few noticed, the theory ofemotions plays a

very central strategic role in Berlin Gestalt Psychology: Köhlerand Koffka

thus conceive of them as the main evidences for theirpsychophysiological

isomorphism hypothesis. Indeed, emotions are conceived asdynamic “Gestalt

qualities” which phenomenally manifest the causal relationsoccurring in the

brain between the events respectively corresponding to thebehavioral

environment and the perceived body. Therefore, they are thephenomena where

the hypothesis of a “manifest organization”, which conditionsthe

psychophysiological isomorphism thesis, can be directly studied.But apart

from this hypothesisaccording to which emotions are thus the phenomenal

correlates of the brain’scausal structures, this approach of emotions has

the specificity of treatingth

em as relations, although of aspecial kind, since they are endowed with a

phenomenally distinct “dynamic”qualitative character, through which they

are precisely supposed to “manifest”the underlying brain causality. Hence,

this approach presents a number of advantages,which make it worth

considering for itself. Indeed, if emotions are thus causalrelations (or

structures) which are directly felt between the figures in theenvironment

and the perceived body, then they simultaneously account for, boththe

“expressive” or “physiognomic” characters (such as “frightening”,

“soothing”,“fascinating”, etc., or even “beautiful”) with which those

figures appear inthe behavioral environment, and the “tendencies towards

action” from whichemotions seem inseparable for the subject who experiences

them: both thosecharacters and tendencies are then relational predicates

expressing the feltcausal relation itself, that is, two different ways, one

subjective, on

eobjective, of talking about the emotion itself, as it is felt between the

subject and the object.Therefore, this conception ofemotions has a

fecundity of its own, independently of the isomorphismhypothesis, a

fecundity which Kurt Lewin notably has developed for itself, bydeveloping a

phenomenology of the emotional and dynamic organization of the sensoryfield

apart from any underlying naturalistic hypothesis. In his Cours à la

Sorbonne, Merleau-Ponty thus explicitly followed the footsteps of Lewin,

byemphasizing the interest of such a structural approach of emotions

andexpressive phenomena, which guided him since La structure du

comportement, while rejecting the naturalisticinspiration of the Berlin

school of Gestalt psychology.However, this “dynamic theory ofemotions”, as

Koffka called it, was also strongly influential on manyphilosophers

(Cassirer, Scheler, Merleau-Ponty) and psychologists (Werner,Buijtendjik,

Tolman, Gibson) through the fundamental genetic status wit

h whichKoffka also endowed the emotional organization of the perceived

world. Findingsupport in the new-born psychology of childhood of his time,

Koffka thussuggested that emotions, thus conceived, would be the primitive

perceptiverelation of living organisms to the world, which would

accordingly first appearto the child through its “expressive” characters,

rather than as a collectionof substantial qualities that would rather

answer a later, more intellectuallyoriented, attentive investigation.

Emotional expressiveness would then be aprimitive biological layer of

perceptual intentionality, from which one couldhopefully be able to trace

the genealogy of the specifically human perceptionand consciousness.One of

the key questions from thatperspective, is to know whether expressive

perception can really be animmediate relation to the world (from which one

could try to derive, as Merleau-Pontydid, even our very perception of

sensory qualities), or if it is not necessaryto gr

ound this relation on a purely qualitative facticity, which would thenonly

gain emotional values from the apprehension of its connections to our ends

1

/

3

100%