Cours Boussaoud Partie 02.pptx

22/11/15

1

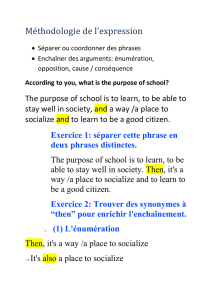

!"#$%&$'()&%*+%&$'(+,,-#$%..+/#(

012+3-+/#(4#(2+(-#15#-15#(6&$4+)#$7+2#(

Driss%Boussaoud!

"#$%&'%($!)%!*%&+%$&+%!,(!-.*/!

3. Apprentissage par renforcement

! Historique sur le renforcement

! Conditionnement, apprentissage

! Apprentissage associatif, basé sur le

renforcement

! Apprentissage par imagerie mentale

! Apprentissage social

Edward L. Thorndike

Williamsburg, Mass.

1874 - New York 1949

Apprentissage, conditionnement

The law of effect

• 0%!1$%2#%$!134&+5657(%!8!9'()#%$!6%!

&5:)#'#5::%2%:'!519$,:';!

• /5:!%<19$#%:&%!6,!16(3!&96=>$%!,?%&!

)%3!&+,'3!16,&93!),:3!6,!@>5#'%A

1$5>6=2%B;!

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence.

La «!boite-problème!» de Thorndike

• C+5$:)#D%!&5:&6('!89#(

7&97(1&),&-7#)#$7(

893(+(:7:(.93*3(4;9$#(

1&$.:89#$1#(,2+3.+$7#(

7#$4(<(=7-#(-#,-&4937'(

#7(3$*#-.#)#$7(7&97(

1&),&-7#)#$7(.93*3(

4;9$#(1&$.:89#$1#(

4:,2+3.+$7#(7#$4(<(=7-#(

3$53>:?(2&3(4#(2;#@#7(

A2+B(&6(#@#17C(

22/11/15

2

Deux formes d’effet : renforcement et

punition, bases du conditionnement

E53#'#F!

.97,'#F!

*%:F5$&%2%:'!

0,!1$5>,>#6#'9!)%!$915:3%!

,(72%:'%!

E(:#'#5:!

0,!1$5>,>#6#'9!)%!$915:3%!

)#2#:(%!

*9&521%:3%!/'#2(6(3!,?%$3#F!

,116#G(9(

/'#2(6(3!,?%$3#F!!

$%'#$9!

*9&521%:3%!

$%'#$9%!(

H($$+(3!I$%)%$#&!/JK..L*!

Susquehanna, Penn. 1904,

Cambridge, Mass. 1990

light

bar

food tray

water

-,7%!)%!/D#::%$!

Conditionnement classique versus opérant

*9&521%:3%!)#31%:39%!#:)91%:),22%:'!)(!&5215$'%2%:'!)(!$,'!

0%!&5215$'%2%:'!)(!$,'!)9'%$2#:%!6,!$9&521%:3%!

-6,33#G(%!!

*9M%<%

N19$,:'!!

O565:',#$%

De l’apprentissage à la mémoire

• 0%!&5:)#'#5::%2%:'!&5:)(#'!8!6,!2925$#3,'#5:!

)%3!$%6,'#5:3!%:'$%!3'#2(6#!5(!%:'$%!3'#2(6#!%'!

&5215$'%2%:'3P!

• 0%!&5:)#'#5::%2%:'!519$,:'!&5:)(#'!8!6,!

F5$2,'#5:!)%!6,!2925#$%!1$5&9)($,6%Q!5(!6,!

2925#$%!)%3!+,>#'()%3!R+,>#'!2%25$4SP!

• T:%!2925#$%!8!65:7!'%$2%Q!)5:'!6%!3(115$'!

:%($5:,6!%3'!6%!&5$'%<!F$5:',6Q!6%3!7,:76#5:3!)%!6,!

>,3%!%'!6%3!3'$(&'($%3!)(!65>%!'%215$,6!29)#,:P!

22/11/15

3

Les différents types de mémoire

U925#$%!

V!&5($'!'%$2%!

@!!U925#$%!)%!'$,?,#6!B!V!65:7!'%$2%!

U925#$%!)%3!F,#'3!

%'!)%3!9?9:%2%:'3!

U925#$%!)%3!

3,?5#$AF,#$%!

-5$'%<!1$9F$5:',6!

/43'=2%!6#2>#G(%!

/43'=2%!F$5:'5A3'$#,',6!

%'!&%$?%6%'!;;;!

W,>#6'93!25'$#&%3!+(2,#:%3!

0%!&5:&%1'!)X,11$%:'#33,7%!

" !0X,11$%:'#33,7%!%3'!(:!&+,:7%2%:'!)(!&5215$'%2%:'!G(#!

$93(6'%!)%!6X%<19$#%:&%!1,339%P!!

" !0,!&,1,&#'9!)X,11$%:)$%!%<#3'%!&+%Y!6%3!%319&%3!,:#2,6%3!

R,:#2,6!6%,$:#:7!'+%5$4S!%'!1%('!Z'$%!1$57$,229%!),:3!)%3!

2,&+#:%3!R2,&+#:%!6%,$:#:7SP!

" !0,!1$%:'#33,7%!?#3%!8!$9)(#$%!6X9&,$'!%:'$%!6,!&5:39G(%:&%!

,''%:)(%!)X(:!&5215$'%2%:'!%'!6,!&5:39G(%:&%!1$5)(#'%P!

" !K6!$93(6'%!)%!6,!16,3'#&#'9!:%($5:,6%Q!5(!:%($516,3'#&#'9;!

0,!:%($516,3'#&#'9!

" !L66%!%<#3'%!2Z2%!),:3!6%!&%$?%,(!

,)(6'%[!

0%3!:%($5:%3!1%(?%:'!25)#\%$!6%($3!

1$51$#9'93!#:)#?#)(%66%3!%'!6%($3!

#:'%$,&'#5:3Q!1,$!6%!>#,#3!)%!

25)#\&,'#5:3!34:,1'#G(%3!R65#!)%!

W%>>S!

-%3!25)#\&,'#5:3!1%$2%''%:'!

)X,11$%:)$%!%'!)%!F5$2%$!)%!

:5(?%,(<!35(?%:#$3Q!2,#3!,(33#!6,!

$9&(19$,'#5:!F5:&'#5::%66%;!

W%>>X3!6,][!^:%($5:3!

'+,'!\$%!'57%'+%$Q!

]#$%!'57%'+%$_!'+%4!

F5$2!&%66!,33%2>6#%3`

22/11/15

4

0X,11$%:'#33,7%Q!(:!&+,21!2(6'#)#3#:,#$%!

" !.%($53&#%:&%3Q!3&#%:&%3!

&57:#'#?%3Q!134&+5657#%Q!29)%&#:%!

)%!6,!$9+,>#6#','#5:Q!3&#%:&%3!)%!

6X9)(&,'#5:_!

" !0X#:'%66#7%:&%!,$'#\&#%66%Q!6,!

$5>5'#G(%Q!3&#%:&%3!)%!6X#:79:#%($Q!

6X#:F5$2,'#G(%Q!2,'+92,'#G(%3!%'!

1+43#G(%P!

" K6!%3'!>,39!3($!6%!$%:F5$&%2%:';!

E$#:,(<!'41%3!)X,11$%:'#33,7%!

L<19$#%:&%!#:)#?#)(%66%! V11$%:'#33,7%!35&#,6!

V11$%:'#33,7%!1,$!

#2,7%$#%!2%:',6%!

S R O

Stimulus Réponse Conséquence

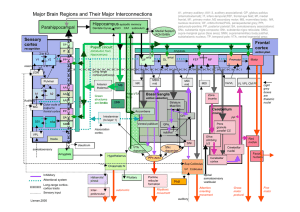

-#$&(#'3!)%!6X,11$%:'#33,7%!1,$!$%:F5$&%2%:'!

a,:76#5:3!

)%!6,!>,3%!

-5$'%<!I$5:',6!

D&-7#E(

F+.+2(

/+$/23+(

Thalamus

Cortico-basal

ganglia loops

+

+

-

G#9-&,2+.%137:(H(13-1937.(4#(2+(4&,+)3$#(

• I:1&),#$.#JK2+3.3-(

• D&4+/#(4#(2;#--#9-(

• L&%*+%&$JM:13.3&$(

GPe

STN

+

-

-

GPi/SNr

Thalamus

+

-

-

Striatum

Cortex

SNc

Dopamine

+/-

+/-

+ + +

22/11/15

5

N O+3-#(49(*:2&(

N D&4#(4#(2+(-&97#(

N P#179-#(QQQ(

(

Neuroplasticité & circuits de la

dopamine !,,-#$%..+/#(+..&13+%6(

• 0,!)9&+,$7%!)%3!:%($5:%3!

)51,2#:%$7#G(%3!)9&+,$7%:'!

)X,(',:'!16(3!F5$'%2%:'!G(%!

6X%$$%($!)%!1$9)#&'#5:!%3'!

7$,:)%P!

• K63!1$5b%''%:'!3($!6%!3'$#,'(2!%'!6%!

&5$'%<!F$5:',6Q!)5:'!#63!25)#\%:'!

6X,&'#?#'9!15($!,),1'%$!6%!

&5215$'%2%:'Q!)%!35$'%!8!

$9)(#$%!6X%$$%($!)%!1$9)#&'#5:;!

Dopamine codage de l’erreur de prediction

!"#$$#%$&'#&($)'*+,*-.&#/,&0")+1$,&#.,$#&01&+-./)2%#.+#&1,,#.'%#&#,&01&

+-./)2%#.+#&($-'%*,#&(1$&0#&+-3(-$,#3#.,4&

Wolfram Schultz and Anthony Dickinson (2000). NEURONAL CODING OF

PREDICTION ERRORS. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000. 23:473–500.

"51,2#:%!25)#\%3!34:,1'#&!%c&,&4!RW%>>S!

#:!F$5:',6!&5$'%<!,:)!>,3,6!7,:76#,!A!U%25$4!

DA

A retenir:

• 0%3!:%($5:%3!)51,2#:%$7#G(%3!b5(%:'!(:!$d6%!

&%:'$,6!),:3!6X,11$%:'#33,7%!1,$!

$%:F5$&%2%:'P!

• K63!)9&+,$7%:'!%:!$%6,'#5:!,?%&!6,!$9&521%:3%!

R$%:F5$&%2%:'S!%'!'5('!9?9:%2%:'!)%!

6X%:?#$5::%2%:'!G(#!6,!1$9)#'!R25'#?,'#5:SP!

• 0,!"V!25)#\%!6,!'$,:32#33#5:!34:,1'#G(%!

),:3!6%3!$97#5:3!&#>6%3!R&5$'%<!F$5:',6!&5$'%<!

%'!7,:76#5:3!)%!6,!>,3%S!!!2925$#3,'#5:;!

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

1

/

10

100%