BRAIN AND LANGUAGE

14, 174-180 (1981)

Asymmetries in the Perceptual Span for Israeli Readers

ALEXANDER POLLATSEK, SHMUEL BOLOZKY,

ARNOLD

D.

WELL, AND KEITH RAYNER

University of

Massachusetts

Native Israeli readers

read Hebrew and English text as their eye movements

were monitored. A window of text moved in synchrony with their eye movements

and the window was either symmetrical about the fixation point or offset to the

left or right. When subjects were reading Hebrew, the perceptual span was

asymmetric to the left and when they were reading English it was asymmetric

to the right. The results point out the importance of attentional factors in reading.

A great deal of research has confirmed that for right-handed subjects,

individual words are processed more efficiently when presented in the

right visual field (to the right of a central fixation location) than in the

left visual field. Early explanations of this asymmetry centered

oh scan-

ning habits that result from experience with reading (Heron, 1957; Mish-

kin & Forgays, 1952). Inherent in much of the recent research on the

topic, however, is the assumption that the processing differences are due

to a functional asymmetry of the brain (Hecaen & Albert, 1978). Ac-

cording to this position, the left hemisphere is more specialized for verbal

processing and the right hemisphere is more specialized for spatial pro-

cessing, so that words are better recognized when presented in the right

visual field and thus initially received by the left or language-specialized

hemisphere.

The scanning explanation predicts that native readers of Hebrew

should show a left-visual-field superiority for words since the direction

of reading is from right to left. However, readers of Hebrew, like readers

of left-to-right languages, show a marked right-visual-field advantage for

the recognition of individual words (Orbach, 1967; Barton, Goodglass,

& Shai, 1956; Carmon, Nachson, & Starinsky, 1976; Silverberg, Bentin,

This research was supported by Grant HD12727 from the National Institute of Child

Health and Human Development (Keith Rayner, principal investigator). The authors thank

Jim Bertera and Robert Morrison for their assistance in conducting the study. Requests

for reprints should be addressed to Alexander Pollatsek, Department of Psychology,

University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003.

174

0093-934Xl81/050174-07$02.00/O

Copyright 0 1981 by Academic Press. Inc.

All rights of reproduction in any form reserved.

ASYMMETRIES IN PERCEPTUAL SPAN

175

Gaziel, Obler, & Albert, 1979). Thus, it has generally been concluded

that although scanning habits may have some influence on perceptual

asymmetries, there is an overriding effect of left-hemisphere superiority

for reading tasks (Jonides, 1979).

It is not clear, however, to what extent conclusions can be made about

the reading of text from studies in which individual words are briefly

displayed to the left or right visual field. Experiments (McConkie &

Rayner, 1976; Rayner, Well, & Pollatsek, 1980) with readers of English

text have confirmed that the perceptual span (the area of text from which

useful information is extracted during a fixation) is asymmetric, with

little information obtained from the left of the fixation point. In these

experiments, eye movement information was monitored and fed into a

computer controlling a cathode-ray tube (CRT) from which the subject

was reading. Changes were made on the CRT on the basis of the location

of the reader’s gaze. For example, a passage of mutilated text was initially

presented on the CRT with every letter from the original text replaced

by an X. However, whenever the reader fixated, a region around the

fixation point changed into readable test. This “window” area moved

in synchrony with the eye movement so that wherever the reader fixated,

the real text was exposed, but everywhere outside the window area the

mutilated text remained. By varying how far the window extends to the

left and right of fixation, it has been possible to determine the extent to

which the perceptual span in reading is asymmetric. The data suggest

that English readers show no difference in performance between (a) a

symmetric window extending 14 characters to the left of fixation and 14

characters to the right of fixation and (b) an asymmetric window ex-

tending 14 characters to the right of fixation but only 4 characters to the

left. On the other hand, if the window extends 14 characters to the left

of the fixation point but only 4 characters to the right, the reading per-

formance of English readers was considerably disrupted.

No experiments dealing with the characteristics of the perceptual span

for readers of Hebrew text have been reported, although there have been

suggestions that the direction of reading and hemispheric specialization

may be important for Hebrew readers (Albert, 1975). If the perceptual

span when reading text is determined by the same factors that are re-

sponsible for asymmetries when processing individual words (presumably

hemispheric specialization), then the perceptual span should be asym-

metric to the right. On the other hand, if the asymmetry of the perceptual

span for readers of English text is due primarily to attentional consid-

erations related to the pattern of eye movements, then the perceptual

span for readers of Hebrew text should be asymmetric to the left. In the

experiments reported here, the technique (Rayner et al., 1980) used

previously to investigate the asymmetry of the perceptual span for Eng-

lish readers was employed to determine if the perceptual span of Israeli

176

POLLATSEK ET AL.

readers is asymmetric to the left or right or is possibly symmetric due

to the conflict between the direction of scanning and hemispheric

specialization.

Israeli readers who were also fluent in English were asked to read

Hebrew sentences and English sentences presented on a CRT as their

eye movements were monitored. The window area around a fixation

point was either symmetric, extending 14 characters both left and right

of fixation, or asymmetric so that it extended either 14 characters left

and 4 right of fixation or 4 left and 14 right of fixation.

METHOD

Subjects

Six native Israeli subjects participated in the study. All were bilingual and the amount

of experience they had reading English varied from 3 to 29 years. They had all received

instruction in reading English beginning in at least the fifth year of school. All of the

subjects were right-handed and none of them required corrective lenses for reading. The

mean age of the subjects was 30 (range = 15-39 years) and two of them were female.

Apparatus and Procedure

Eye movements were recorded with a dual Purkinje eye tracker (Stanford Research

Institute) that was interfaced with a Hewlett-Packard 2100 computer. The eye tracker has

a resolution of 10 arcmin, and the output is linear over the visual angle (14 deg) occupied

by the sentences. Subjects’ heads were fixed by a bite bar. The subject’s eye was 46 cm

from the CRT used to present the sentences; three characters equaled 1 deg of visual

angle. Details of the apparatus have been described by Rayner et al. (1980).

At the beginning of the experiment each subject read some warm-up sentences with the

window offset either to the left or right of fixation. Following the warm-up sentences, each

subject read 16 Hebrew sentences in each of the 3 experimental conditions. Sentences

were read in blocks of 8 with the window either being symmetrical around the fixation

point, asymmetric to the right or asymmetric to the left. Subjects returned to the laboratory

on another day and read 48 English sentences, 16 in each of the conditions in the same

manner as the Hebrew sentences had been read. The English sentences were similar in

length and structure to English translations of the Hebrew sentences. For both Hebrew

and English sentences, the order of the conditions and the sentences read were counter-

balanced across subjects.

Subjects were instructed to read each sentence and then report the sentence to the

experimenter. They were instructed to report the sentence verbatim or to paraphrase it.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

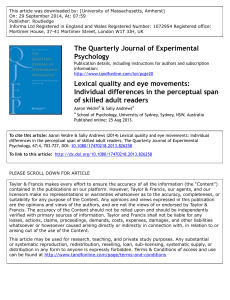

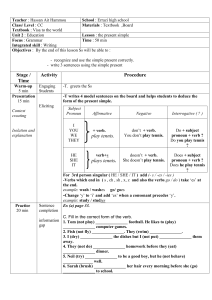

With Hebrew text, reading performance (See Table 1 and Figure 1)

did not differ between the symmetric condition and the asymmetric con-

dition in which the window was shifted to the left. Conversely, when

subjects read English text, their performance was similar to that of native

English readers in that the symmetric condition did not differ from the

asymmetric condition in which the window was shifted to the right. As

can be seen in Table 1, the Israeli subjects read English (in the symmetric

and asymmetric right conditions) at the rate of 230 wpm (words per

ASYMMETRIES IN PERCEPTUAL SPAN

177

TABLE 1

EFFECTIVE READING RATES IN WORDS PER MINUTE FOR THE ISRAELI SUBJECTS READING

HEBREW SENTENCES AND ENGLISH SENTENCE< COMPARED TO AMERICAN SUBJECTS

READING COMPARABLE ENGLISH SENTENCES

Window

condition

Israeli subjects

Hebrew English English speaking

subjects

14-14 286 233 350

14-4 282 131 218

4-14 185 221 336

minute). Native English-speaking subjects’ typical reading rates are be-

tween 320 and 350 wpm on sentences of similar length and complexity.

We assume that the slower reading rate for the Israeli subjects on English

sentences is because English is not their native language. However, it

is instructive to note that for all of the variables shown in Table 1 and

Figure 1, the window offset had the same effect as it did for English

readers reading English. For both types of text, the asymmetric condition

in which the window was shifted in the direction opposite to that of

reading resulted in marked decrements in reading behavior.

-Hebrew

.i ‘%j :------r;,:

2

Asymmtrlc Symmetric Asymmatric

Left Right

FIG.

1. Mean saccade length, mean fixation duration, and number of fixations for

Hebrew and English text.

178

POLLATSEK ET AL.

When reading Hebrew, performance m the 14L-4R condition was

superior to that in the 4L-14R condition for each of the six subjects with

the exception of a reversal for a single subject on the fixation duration

measure. For reading rate, mean saccade length and mean number of

fixations per line, the results were highly significant, t(5) = 4.10, 7.45,

and 4.61, respectively, p < .Ol, whereas for average fixation duration,

the difference was not significant, t(5) = 1.26, p > .20. When reading

English, performance in the 4L-14R condition was superior to that in

the 14L-4R condition for each of the six subjects, with the exception

of a reversal for a single subject on the fixation duration measure. For

mean saccade length and mean number of fixations per line, the differ-

ences were highly significant, t(5) = 3.39 and 4.04, respectively, p <

.02, while for reading rate and mean fixation duration the results failed

to reach conventional levels of significance, t(5) = 2.39 and 2.52, re-

spectively, .05 < p < .10. However, this reduced level of significance

for reading rate was due to one subject who had a much larger difference

than the others which inflated the error term. If this subject who showed

the largest asymmetry (a difference of 292 wpm vs. an average difference

of 57 wpm for the other five subjects) is removed from the analysis, then

the difference in reading rate for the other five subjects is highly signif-

icant, t(4) = 5.16, p < .Ol.

These results provide an unambiguous demonstration that during the

reading of meaningful text, the direction of reading (and not hemispheric

specialization) primarily determines the asymmetry of the perceptual

span. For each of the six bilingual subjects, the perceptual span was

asymmetric to the left when Hebrew was read and asymmetric to the

right when English was read.

It is interesting to note that Hebrew varies structurally and ortho-

graphically from English in some important ways that are relevant to our

experiment. In Hebrew, many function words are clitic, i.e., are attached

like prefixes or suffixes to content words. Furthermore, unlike English,

not all vowels are represented in Hebrew orthography. The net effect

of these differences is that Hebrew sentences normally contain fewer

words than their English counterparts. In our case, for example, the

Hebrew sentences were translations of English sentences, and the He-

brew sentences were shorter than the English versions by approximately

1.3 words per sentence. Thus while the Israeli readers reading Hebrew

are markedly slower than American readers reading English (see Table

l), when measured by words per minute, this may be accounted for by

the above structural and orthographic differences. As a quick check that

there was nothing abnormally slow about our Hebrew readers, we com-

puted the reading rate in Hebrew based on the number of words contained

in the English translations of the Hebrew sentences. Using this measure,

the average reading rate for our native Israeli subjects reading Hebrew

6

6

7

7

1

/

7

100%