H LES BÉNÉFICES DU TRAITEMENT

HTA

La Lettre du Cardiologue - n° 365 - mai 2003

22

LES BÉNÉFICES DU TRAITEMENT

ANTIHYPERTENSEUR : LES PREUVES

DANS LES ESSAIS INTERNATIONAUX

Les premiers essais à grande échelle portant sur l’efficacité des

traitements antihypertenseurs dans la morbidité cardiovasculaire

ont comparé la fréquence de survenue d’événements cardiovas-

culaires chez des hypertendus traités soit par placebo, soit par un

traitement antihypertenseur basé alors principalement sur les bêta-

bloquants, les diurétiques et les antihypertenseurs d’action cen-

trale. Les premières études, réalisées dans les années 60 et 70,

ont apporté une démonstration claire des bénéfices du traitement

dans le cadre de l’HTA sévère. Les études réalisées ensuite, au

cours des années 80, ont démontré que les bénéfices du traite-

ment concernaient non seulement les sujets ayant une HTA sévère,

mais également ceux atteints d’une HTA légère à modérée. La

méta-analyse de ces études a montré que la baisse tensionnelle

induite par un traitement antihypertenseur réduisait en moyenne

de 42 % le risque d’accident vasculaire cérébral et aussi, mais à

un moindre degré, le risque d’accident coronarien de 14 % (1).

L’arrivée des nouvelles molécules antihypertensives et le vieillis-

sement de la population ont généré de nouvelles questions, appa-

rues au milieu des années 80.

Première question : y a-t-il un bénéfice réel

à traiter l’HTA du sujet âgé ?

Bien que l’existence d’une augmentation du risque cardiovascu-

laire lié à une pression artérielle élevée ait été démontré depuis

les années 70 chez les sujets âgés, l’utilité de les traiter n’a été

mise en évidence que beaucoup plus tard. Plusieurs études cli-

niques ont clairement montré qu’un traitement antihypertenseur

était capable de réduire la morbidité et la mortalité chez le sujet

âgé jusqu’à 85 ans. Les études STOP I et II (2, 3) et MRC-2 (4)

ont mis en évidence les bénéfices de tels traitements chez le sujet

âgé ayant une HTA systolo-diastolique, alors que SHEP (5),Syst-

Eur (6) et Syst-China (7) ont montré des bénéfices similaires chez

le patient âgé ayant une HTA systolique isolée. Ces bénéfices

semblent même être plus importants que pour les hypertendus

d’âge moyen, en particulier pour la prévention des complications

coronaires.

Deuxième question : est-ce que les médicaments

les plus récents offrent une protection plus

(ou moins) importante que les médicaments dits

conventionnels (diurétiques et bêtabloquants) ?

De très nombreux essais cliniques ont essayé de répondre à cette

question, mais leurs résultats sont souvent discordants. Certaines

études ont montré que les “nouveaux venus” (essentiellement les

IEC et les antagonistes calciques) faisaient aussi bien que les

“classiques” (diurétiques et bêtabloquants) : c’est le cas des études

STOP II (IEC versus dihydropyridines versus diurétiques chez

les sujets âgés) (3), NORDIL (diltiazem versus diurétiques/bêta-

bloquants) (8) et INSIGHT (nifédipine versus diurétiques) (9).

D’autres études ont montré que, même s’il n’y avait pas de dif-

férence sur le critère principal (dans la plupart des cas, il s’agis-

sait de la mortalité cardiovasculaire), les nouvelles classes pré-

sentaient certains avantages sur des critères secondaires. Ainsi,

l’étude CAPP (10) ne note pas de différence entre les deux stra-

tégies thérapeutiques (captopril versus diurétiques/bêtabloquants)

sur le critère principal (ensemble des événements cardiovascu-

laires mortels et non mortels) et fait apparaître une tendance non

significative à la diminution de la mortalité cardiovasculaire dans

le groupe captopril ; toutefois, elle observe deux différences signi-

ficatives vis-à-vis de critères secondaires [AVC plus nombreux

chez les hypertendus traités par captopril (+ 25 %), et une inci-

dence de nouveaux cas de diabète plus faible dans le groupe cap-

topril].

L’étude LIFE (11) a montré un bénéfice de l’antagoniste des

récepteurs AT1 (losartan 50 mg/j) par rapport à un bêtabloquant

(aténolol 50 mg/j) chez des patients hypertendus à haut risque

cardiovasculaire lié à une hypertrophie ventriculaire gauche

(HVG).

Les résultats récents de l’étude ALLHAT viennent d’animer la

controverse autour de cette question des médicaments les plus

récents (12). L’étude ALLHAT est la plus importante étude

Stratégies thérapeutiques et prévention cardiovasculaire

chez le patient hypertendu :

des données des essais cliniques à la décision pratique

Therapeutic strategies and cardiovascular prevention for patients with high blood pressure

●A. Bénétos*, D. Pouchain**

*CHU Nancy ; ** MCU-UFR Créteil.

La Lettre du Cardiologue - n° 365 - mai 2003

23

HTA

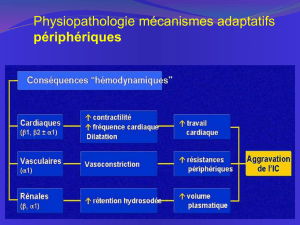

contrôlée jamais réalisée : 42 448 sujets hypertendus ayant au

moins un autre facteur de risque (FdR) cardiovasculaire ont été

inclus et suivis pendant près de cinq ans. À l’origine, il y avait

quatre groupes pharmacologiques en double aveugle : un IEC

(lisinopril), un antagoniste calcique (amlodipine), un alphablo-

quant (doxazosine) et un diurétique (chlortalidone). Le but de

l’étude était de déterminer si les médicaments les plus récents

étaient supérieurs, égaux ou inférieurs au diurétique en termes de

protection coronarienne. Il y a environ deux ans, le comité de sur-

veillance de cette étude a observé une surmortalité par insuffi-

sance cardiaque dans le groupe doxazosine, ce qui a conduit les

responsables de l’étude à interrompre ce groupe et à poursuivre

avec les trois autres (13). Les résultats définitifs ont montré que,

sur le critère principal (morbidité et mortalité coronaire), les trois

médicaments avaient des effets équivalents. Par contre, le groupe

“diurétique” avait certains avantages sur des critères secondaires,

ce qui a conduit les investigateurs (en tenant également compte

du plus faible coût de ce traitement) à suggérer que les diuré-

tiques étaient la meilleure première étape thérapeutique pour trai-

ter les hypertendus. Un des résultats marquants de cette étude

était le nombre de patients traités par association médicamen-

teuse. En effet, si au début (sixième mois) de l’étude plus de 70 %

des patients étaient sous monothérapie antihypertensive, ce pour-

centage est passé à environ 35 % à la fin de la cinquième année

de traitement (figure 1). Les patients sous bithérapie sont passés

respectivement de 20 à 35 %, alors que ceux traités par au moins

trois médicaments sont passés de 5 % au début de l’étude à

environ 30 % à la fin du suivi.

Les conséquences de cette tendance sur le contrôle tensionnel

sont claires : de 27,4 % de sujets contrôlés après six mois de trai-

tement, on passait à 65,6 % à la fin de l’étude. Il faut aussi noter

que les trois groupes ont reçu le plus souvent un bêtabloquant

comme second médicament. À la lecture de ces résultats, une

question s’impose en priorité : peut-on vraiment parler d’un avan-

tage des diurétiques versus les IEC et/ou les antagonistes cal-

ciques, ou bien peut-on suggérer les avantages d’une bi- ou d’une

trithérapie versus une autre polythérapie ?

Troisième question : faut-il s’acharner pour faire

baisser la PA à un niveau très bas ?

C’est l’étude HOT qui devait permettre de répondre à cette ques-

tion majeure, tant sur le plan clinique que sur le plan pharmaco-

économique. Il s’agissait de la plus ambitieuse des études des

années 90, avec plus de 19 000 hypertendus suivis pendant

cinq ans (14). Cette étude a cherché à savoir si la prévention des

complications cardiovasculaires, grâce aux traitements antihy-

pertenseurs, était proportionnelle au degré de la baisse tension-

nelle. Le nombre de complications cardiovasculaires a été com-

paré dans trois populations d’hypertendus, chez lesquels différentes

pressions diastoliques cibles étaient fixées ( 90 mmHg,

85 mmHg, 80 mmHg).

Le protocole imposait l’ordre et la stratégie de prescription : début

du traitement par un antagoniste calcique de la classe des dihy-

dropyridines de longue durée d’action (félodipine), puis, en cas

d’efficacité insuffisante, association à un IEC ou à un bêtablo-

quant à faible dose, puis doublement de la dose de félodipine,

puis doublement de la dose d’IEC ou de bêtabloquant, puis diu-

rétique. Le premier résultat de l’essai était que 88 % des patients

du groupe “objectif PAD 90 mmHg” ont atteint le seuil ten-

sionnel fixé, alors que ce pourcentage était de 55 % dans le groupe

“objectif PAD 80 mmHg”. Pour obtenir ces résultats, une large

majorité des patients a été traitée par une association d’antihy-

pertenseurs. Ainsi, alors qu’à leur inclusion dans l’étude, près de

60 % des patients étaient traités par monothérapie, ils n’étaient

plus que 32 % à la fin de l’étude (figure 2). À noter que dans le

groupe ayant comme objectif une PAD 80 mmHg, seul un

patient sur quatre était traité par monothérapie à la fin de l’étude.

Figure 1. Nombre de traitements antihypertenseurs nécessaires au

contrôle tensionnel dans l’étude ALLHAT (23).

Source : J Clin Hypertens © 2002 Le Jacq Communications, Inc. Figure 2. Proportion de polythérapies antihypertensives nécessaires au

contrôle de la pression artérielle diastolique dans l’étude HOT (24).

La Lettre du Cardiologue - n° 365 - mai 2003

24

HTA

Lorsque le nombre d’événements cardiovasculaires est analysé

en fonction du niveau diastolique effectivement atteint, l’effica-

cité clinique de la prévention était d’autant plus importante que

la pression diastolique était plus basse. Sur l’ensemble des évé-

nements cardiovasculaires, la valeur optimale correspondant au

risque minimal de complication était d’environ 83 mmHg pour

la PAD et de 138 mmHg pour la PAS. Les deux messages cen-

traux de l’étude HOT sont les suivants :

1. Baisser la PA à 140/85 mmHg présente un bénéfice clinique

pour le patient hypertendu.

2. Pour atteindre cet objectif, plus de deux patients sur trois ont

besoin d’une association d’antihypertenseurs.

Quatrième question : l’utilisation des associations

thérapeutiques a-t-elle un intérêt majeur

dans la stratégie thérapeutique ?

À l’exception d’une ou deux études, la majorité des patients des

essais cliniques étaient traités en fin de l’étude avec une associa-

tion thérapeutique comportant le plus souvent deux ou trois médi-

caments antihypertenseurs (Syst-Eur [6], SHEP [5], ALLHAT

[12], HOT [13], STOP II [3], Progress [15]). Dans toutes ces

études, les associations thérapeutiques représentaient plus de

50 % des traitements, et étaient d’autant plus fréquentes que les

critères de contrôle de l’HTA étaient stricts. Une étude récente

(9)fait exception à cette règle. Elle a comparé les effets de la nifé-

dipine à libération prolongée à ceux d’un diurétique mixte (thia-

zidique plus épargneur de potassium). À la fin de cette étude, près

de 70 % des patients étaient sous nifédipine seule, et la pression

artérielle était en moyenne de 140/85 mmHg. Cette efficacité thé-

rapeutique a eu un prix : de nombreux patients ont dû arrêter

l’étude à cause des effets indésirables, notamment des œdèmes

des membres inférieurs (30 %). En effet, la grande majorité des

patients a reçu des doses élevées de nifédipine (60 mg) afin que

leur PA soit bien contrôlée.

Quant aux multiples possibilités d’association entre les différentes

familles d’antihypertenseurs, seules certaines sont pharmacolo-

giquement et cliniquement rationnelles. Quatre associations sont

citées dans les recommandations de l’ANAES (16) pour la prise

en charge des patients adultes atteints d’une hypertension arté-

rielle essentielle :

✓Bêtabloquants + diurétiques : association la plus utilisée dans

les essais cliniques des années 80, a montré son efficacité versus

placebo et constitue actuellement la stratégie de référence pour

évaluer l’efficacité des nouvelles classes médicamenteuses

(exemple étude STOP II).

✓Diurétiques + IEC (ou ARA2) : association rencontrée dans

les études où un IEC (ou un ARA2) était utilisé comme premier

médicament (STOP II, CAPP, LIFE). Logique sur le plan phy-

siopathologique, efficace et en général bien tolérée, c’est l’asso-

ciation fixe la plus pratiquée.

✓Bêtabloquants + antagonistes calciques (dihydropyridines) :

association utilisée dans certaines études (par exemple ALLHAT),

mais peu employée en pratique quotidienne.

✓Antagonistes calciques + IEC : une des associations les plus

utilisées dans les essais cliniques, surtout dans ceux ayant comme

première étape un anticalcique (HOT, Syst-Eur, Syst-China, etc.).

Effets antihypertenseurs synergiques et absence d’effet biolo-

gique indésirable sont ses deux grands avantages.

Pour toutes ces associations, le recours à des doses fixes permet

de simplifier la prescription et l’observance pour un coût finan-

cier plus faible, et le développement de faibles dosages peut avoir

un intérêt du point de vue de la tolérance.

EN PRATIQUE

À l’issue de cette revue des données actuelles de la science, une

certitude est bien établie : il existe un bénéfice clinique en termes

de morbimortalité à faire baisser la pression artérielle des patients

hypertendus, quelles que soient les modalités thérapeutiques

employées. Par ailleurs, le bénéfice du traitement est d’autant plus

important que le risque cardiovasculaire individuel absolu des

patients est élevé.

Le corollaire à ce constat s’inscrit dans la pratique par la ques-

tion suivante : comment intégrer les informations valides et de

plus en plus nombreuses dans la décision individuelle concernant

un patient dont le profil n’est pas forcément celui des patients

inclus dans les essais ?

En pratique, il y a deux grandes catégories de situations cliniques :

le patient ayant une HTA débutante et chez qui il est justifié d’ins-

taurer un traitement antihypertenseur, et le patient déjà traité pour

hypertension, ayant épuisé les différentes monothérapies pour

une raison ou pour une autre, et dont le contrôle tensionnel est

insatisfaisant.

La prescription initiale

Le choix de la classe pharmacologique du premier traitement

antihypertenseur en monothérapie dépend davantage des carac-

téristiques du patient et de ses comorbidités que des chiffres ten-

sionnels eux-mêmes. Pour le patient hypertendu “idéal”, c’est-

à-dire celui âgé de moins de 65 ans atteint d’une HTA légère à

modérée et n’ayant aucune comorbidité, les recommandations

de l’ANAES (16) s’appliquent relativement bien, et les quatre

classes pharmacologiques peuvent être utilisées, en privilégiant,

à rapport bénéfice/risque comparable, le meilleur rapport

coût/efficacité (diurétiques et bêtabloquants). En fait, le patient

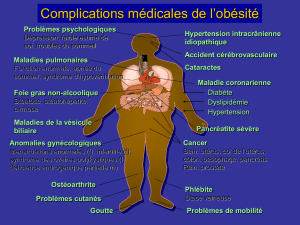

hypertendu “idéal” est le plus rare, et la majorité des patients

hypertendus ont une ou plusieurs comorbidités (cardiovascu-

laires ou non) qui guident en partie le choix initial. Par exemple,

si le patient est coronarien, il est plus judicieux de lui proposer

un bêtabloquant, ou éventuellement un inhibiteur calcique. S’il

est diabétique, un IEC ou un ARA2, surtout s’il existe une

néphropathie (IDNT), est le choix de première intention, sans

oublier totalement les bêtabloquants (17). S’il existe une HVG

(éventualité rare au début d’une HTA), un ARA2 est plus adapté

(11).En cas d’insuffisance rénale, un IEC ou un ARA2 (18) sont

plus indiqués.

Il existe aussi des comorbidités non cardiovasculaires qui peu-

vent influencer le choix de première intention (19). Par exemple,

un asthme associé doit faire renoncer aux bêtabloquants, mais

une maladie migraineuse active les privilégie. Au fil du temps, la

poursuite de la monothérapie de première intention est condi-

tionnée par l’atteinte des objectifs tensionnels (PA < 140/90, ou

<150 chez les sujets âgés, ou < 140/80 chez les diabétiques) et

la tolérance clinique et/ou biologique.

L’évolution vers les bithérapies

Comme le montrent un grand nombre d’essais d’intervention,

mais aussi les études épidémiologiques et les statistiques des

caisses d’assurance maladie, un grand nombre de patients (en par-

ticulier les diabétiques et les patients dont l’HTA est ancienne)

ont besoin d’une bithérapie, voire d’une trithérapie pour équili-

brer leurs chiffres tensionnels à un moment donné de leur évolu-

tion (14, 15, 21, 22). Le choix de la bithérapie tient compte des

mêmes considérations que celui des monothérapies : patient

“idéal” à qui il est possible de tout proposer, et patient atteint de

comorbidités cardiovasculaires ou non cardiovasculaires condi-

tionnant en partie le choix. De plus, le choix de la bithérapie est

guidé par deux éléments supplémentaires :

1. La tolérance des différents médicaments qui ont pu être utili-

sés en monothérapie. Par exemple, un patient ayant mal toléré les

bêtabloquants en monothérapie n’est pas un bon candidat à une

association bêtabloquant-diurétique ou bêtabloquant-inhibiteur

calcique.

2. La stratégie des paniers thérapeutiques (20), qui suggère d’as-

socier deux médicaments de paniers différents avec une préfé-

rence pour les associations comprenant un diurétique selon

l’ANAES (16), et un diurétique obligatoire en cas de trithérapie

(sauf contre-indication).

Enfin, l’ANAES recommande de privilégier les associations fixes

en une prise par jour. Dans ce cadre, les associations disponibles

s’appuient essentiellement sur les diurétiques qui existent en asso-

ciation avec les IEC, les ARA2 et les bêtabloquants, et sur les

inhibiteurs calciques qui existent en association avec les bêta-

bloquants et les IEC.

CONCLUSION

Si ce sont les chiffres de pression artérielle qui décident de la mise

en route du traitement ou de son adaptation, ce ne sont pas eux

qui guident le choix pharmacologique du traitement, qui est

davantage conditionné par les comorbidités cardiovasculaires ou

non cardiovasculaires des patients, les synergies des associations

médicamenteuses et les effets indésirables. ■

Bibliographie

1. Collins R, Richard P, MacMahon S et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary

heart disease : Part 2, short-term reductions in blood pressure : overview of ran-

domized drug trials in their epidemiologic context. Lancet 1990 ; 336 : 827-38.

2. Dahlöf B, Lindholm LH, Hansson L, Schersten B, Ekbom T, Wester PO.

Morbidity and mortality in the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension

(STOP-Hypertension). Lancet 1991 ; 338 : 1281-85.

3. Hansson L, Lindholm LH, Ekbom T et al. Randomised trial of old and new

antihypertensive drugs in elderly patients : cardiovascular mortality and morbi-

dity - The Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 study. Lancet 1999 ;

354 : 1751-6.

4.MRC Working Party : Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hyper-

tension in older adults : principal results. Br Med J 1992 ; 304 : 405-12.

5. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug

treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the

Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA 1991 ; 265 : 3255-64.

6. Fagard RH, Staessen JA, Thijs L et al. Response to antihypertensive therapy in older

patients with sustained and nonsustained systolic hypertension. Systolic Hypertension

in Europe (Syst-Eur) Trial Investigators. Circulation 2000 ; 102 : 1079-81.

7. Liu L, Wang JG, Gong L, Liu G, Staessen JA.Comparison of active treatment

and placebo in older Chinese patients with isolated systolic hypertension. Systolic

Hypertension in China (Syst-China) Collaborative Group. J Hypertens 1998 ;

16 : 1823-9.

8. Hansson L, Hedner T, Lund-Johansen P et al. Randomised trial of effects of

calcium antagonists compared with diuretics and beta-blockers on cardiovascu-

lar morbidity and mortality in hypertension : the Nordic Diltiazem (NORDIL)

study. Lancet 2000 ; 356 : 359-65.

9. Brown M, Palmer C, Castaigne A et al. Morbidity and mortality in patients

randomised to double blind treatment with long activity calcium channel blocker

or diuretic (INSIGHT study). Lancet 2000 ; 356 : 366-72.

10. CAPP Study investigators. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibi-

tion compared with conventional therapy on cardiovascular morbidity and mor-

tality in hypertension : the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPP) randomized

trial. The Captopril Prevention Project (CAPP) Study Group. Curr Hypertens Rep

1999 ; 1 : 466-7.

11. Dahlöf B, Devereux RB, Kjeldsen SE et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and

mortality in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension

study (LIFE) : a randomised trial against atenolol. Lancet 2002 ; 359 : 995-1003.

12. The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative

Research Group. Major cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients rando-

mized to doxazosin vs chlortalidone : the antihypertensive and lipid-lowering

treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). ALLHAT Collaborative

Research Group. JAMA 2000 ; 283 : 1967-75.

13. The ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative

Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized

to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diure-

tic : the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack

Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA 2002 ; 288 : 2981-97.

14. Hansson L et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose

aspirin in patients with hypertension : principal results of the Hypertension

Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998 ; 351 : 1755-62.

15. PROGRESS Collaborative Study Group. Randomised trial of perindopril

based blood pressure-lowering regimen among 6 108 individuals with previous

stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet 2001 ; 358 : 1033-41.

16. ANAES (Agence Nationale d’Accréditation et d’Évaluation en Santé) : Rapport

2000. Prise en charge des patients adultes atteints d’hypertension artérielle essentiel-

le. Recommandations cliniques et données économiques. Texte des recommandations.

17. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk

of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. UKPDS38.

Br Med J 1998 ; 317 : 703-13.

18. Keane WF, Brenner BM, De Zeeuw D et al. for the Renaal Study Investigators.

The risk of developing end-stage renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes and

nephropathy : The RENAAL Study. Kidney Int 2003 ; 63 : 1499-507.

19. Guidelines Sub-Committee. 1999 World Health Organization-International

Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension.

J Hypertens 1999 ; 17 : 151-83.

20. Dickerson JEC, Hingorani AD, Ashby MJ, Palmer CR, Brown MJ.

Optimisation of antihypertensive treatment by crossover rotation of four major

classes. Lancet 1999 ; 353 : 2008-13.

21. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, De Zeeuw D et al. Effects of losartan on renal and

cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy.

N Engl J Med 2001 ; 345 : 861-9.

22. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR et al. Renoprotective effect of the angio-

tensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2

diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001 ; 345 : 851-60.

23. Cushman WC, Ford CE, Cutler JA et al. Success and predictors of blood pres-

sure control in diverse North American settings: the antihypertensive and lipid-

lowering treatment to prevent heart attack trial (ALLHAT). J Clin Hypertens

2002 ; 4 (6) : 393-405.

24. Hansson L et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose

aspirin in patients with hypertension : principal results of the Hypertension

Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. Lancet 1998 ; 351 : 1755-62.

La Lettre du Cardiologue - n° 365 - mai 2003

25

HTA

1

/

4

100%

![Bon à savoir : [ téléchargez le pdf ]](http://s1.studylibfr.com/store/data/004734379_1-5dc131716acb5df5c8dd113e210de694-300x300.png)