Télécharger l'article au format PDF

L’Encéphale (2010) 36S, D7—D13

Disponible en ligne sur www.sciencedirect.com

journal homepage: www.em-consulte.com/produit/ENCEP

MÉMOIRE ORIGINAL

Vécu subjectif du recontact téléphonique après

tentative de suicide

Patient satisfaction regarding further telephone contact following

attempted suicide

G. Gruata, O. Cottencinb,∗, F. Ducrocqa, S. Duhemc, G. Vaivaa

aService de psychiatrie adulte, CHRU de Lille, Lille, France

bService d’addictologie, université Lille-2, CHRU de Lille, 57, boulevard de Metz, 59037 Lille cedex, France

cCIC, CHRU de Lille, Lille, France

Received 31 December 2008; accepted 7 September 2009

Available online 1 d´

ecembre 2009

MOTS CLÉS

Tentative de suicide ;

Récidive suicidaire ;

Recontact

téléphonique ;

Satisfaction

Résumé La satisfaction des usagers des systèmes de soins est assez peu étudiée dans le

domaine du suicide. Pourtant, dès 1976, certains auteurs retrouvaient un lien entre le risque

suicidaire et un faible niveau de satisfaction envers les soins. À ce jour, seules deux études

consacrées à la prise en charge des patients suicidants comportaient une évaluation de la satis-

faction des patients (retrouvant d’ailleurs un lien fort entre insatisfaction et risque suicidaire).

Au cours de l’étude SYSCALL mesurant l’impact d’un recontact téléphonique systématique sur

la récidive dans les semaines suivant une tentative de suicide, nous avons voulu savoir si cette

procédure ainsi que ses modalités avait été bien acceptée par les patients. Lors du dernier

recontact programmé 13 mois après la tentative de suicide index, nous avons évalué le vécu

des patients face à cette intervention et son impact sur leur devenir au moyen d’un ques-

tionnaire : 54% des patients interrogés ont répondu, 78,9 % d’entre eux considéraient que le

recontact leur avait été bénéfique et 40,4 % estimaient qu’il avait eu une influence sur leur

vie voire pour 29,4 % qu’il leur avait évité une récidive suicidaire ; 94,5 % étaient satisfaits de

son déroulement, mais 20,2 % auraient aimé être recontactés par un médecin connu. Enfin,

la majorité des patients recontactés étaient satisfaits du moment choisi. Le recontact télé-

phonique, malgré sa nature intrusive et inhabituelle, a été bien accepté par les patients, ainsi

que ses modalités. Nous pensons que le recueil de l’opinion des patients est aussi à développer

en tant qu’outil thérapeutique dans la prise en charge des suicidants.

© L’Encéphale, Paris, 2009.

∗Auteur correspondant.

E-mail address: [email protected] (O. Cottencin).

0013-7006/$ — see front matter © L’Encéphale, Paris, 2009.

doi:10.1016/j.encep.2009.10.009

D8 G. Gruat et al.

KEYWORDS

Telephone contact;

Suicide attempt;

Recurrence of suicide

attempt;

Client satisfaction

Summary At a time when increasing importance is given to providing satisfaction to the users

of health services, it is surprising that this concept has hardly ever been examined in the field of

suicide. Although suicide (prevention and management) is an important part of public health,

there seems to be little interest in finding out patients’ opinions about the healthcare services

which are offered to them. Back in 1976, some authors found a link between the risk of suicide

and a low level of satisfaction of healthcare. To date, only two studies looking at management of

suicidal patients have included an assessment of patient satisfaction (a strong link between dis-

satisfaction and suicidal risk was found). During the SYSCALL study, which measured the impact

of systematic recontacting by telephone on recurrence of suicide, in the weeks following a

suicide attempt, we aimed to find out if this procedure and its methods were well-accepted by

the patients. When the patients were first recontacted, 13 months after the suicide attempt,

and included in our study, we assessed by means of a questionnaire, their experience of being

faced with this intervention, and its impact on their future. Of the 605 patients included, 312

were put into the control group, 147 were recontacted at the end of the first month, and 146 at

the end of the third month. The rate of repeat suicide attempts in the year following the initial

attempt, was significantly lower in the group that was recontacted after one month, than in

the control group [12% against 22%; P= 0.03]. It would therefore seem that systematic recon-

tacting by telephone one month after attempted suicide may have contributed in reducing the

risk of an early repeat suicide attempt. Of the 482 patients whom we managed to contact by

13 months, 254 had filled out the questionnaire about their subjective experience, in writing or

by telephone, this making a response rate of 52.7%. Amongst the patients who replied, female

patients are over-represented with more of them being recontacted than males, but no dif-

ference was found in the psychiatric symptomatology observed when they were assessed and

included in the study. On the other hand, we found a higher incidence of mood disorders and

suicidal risk in those who were examined at the final assessment at 13 months. A large majority

(78.9%) of the patients who were recontacted, considered recontacting as beneficial, 40.4%

considered that it had influenced their lives, and 29.4% thought that recontacting had con-

tributed to avoiding them making a further suicide attempt. Out of the patients recontacted,

94.5% had appreciated the person that had recontacted them, and only 8.3% had been disturbed

at being recontacted by a different doctor than the one whom they had met in the Emergency

department. A majority of them (54.1%) considered that telephoning was the most appropriate

method for recontacting, but of those who were not convinced of being recontacted by tele-

phone, 89.5% of them thought that consultation was the best alternative. Finally, around a third

of patients would have preferred being recontacted earlier. On closer examination of the 10

recontacted patients who were dissatisfied by being recontacted, we did not find any elements

to characterize them, except for a previous history of more suicide attempts in their family.

Finally, a majority of the dissatisfied patients would have preferred being notified in advance

of the time of recontacting, and half of them thought that recontacting was too late, but they

were not disturbed by being contacted by a different doctor. Telephone recontacting and its

methods were surprisingly well-accepted by the patients, even though it is intrusive in nature

and unusual in France. We think that despite the inevitable bias that is linked to it, the opinion

of patients should be sought and developed in the management of patients who have attempted

suicide and in the treatment of the suicidal crisis in general. Even though patients’ satisfaction

rates may improve the quality of treatment, we should bear in mind that listening to, noting

down and examining patients’ opinions and words, is in itself a useful factor for patients in

their quest for improving their health.

© L’Encéphale, Paris, 2009.

Introduction

À l’heure où une importance grandissante est accordée à la

satisfaction des usagers des systèmes de soins, il est assez

surprenant que dans le domaine du suicide, cette notion

soit si peu explorée. Pourtant, le suicide fait partie des

enjeux importants de santé publique et, dans le domaine

de sa prévention, la prise en charge des patients après une

tentative de suicide est un sujet de recherche prioritaire.

Pourtant, dès 1976, Richman et Charles retrouvaient un lien

entre le risque suicidaire et un faible niveau de satisfac-

tion envers les soins [15], ce que confirmera Lebow dans sa

revue de littérature sur la satisfaction en psychiatrie [10].

Parmi les nombreuses études consacrées à la prise en charge

des patients après tentative de suicide, seules quelques-

unes ont étudié le recueil du point de vue des patients dont

deux portaient sur les systèmes d’intervention au décours

d’un geste suicidaire [2,6]. La première retrouvait un indice

moyen de satisfaction plus élevé chez les patients ayant

bénéficié de séances de psychothérapie à leur domicile que

chez ceux ayant eu la prise en charge usuelle [6]. La sec-

onde évaluait une prise en charge psychosociale réalisée

par un intervenant spécialisé dans le suicide et retrouvait

parmi les répondeurs 76 % de satisfaction avec un lien net

Vécu subjectif du recontact téléphonique après tentative de suicide D9

entre insatisfaction et risque suicidaire [2]. Plusieurs fac-

teurs peuvent expliquer ce manque de données : la réticence

des soignants à se sentir jugés, les biais inhérents au recueil

de l’opinion des patients, le manque de concertation sur le

terme «satisfaction ». Pourtant, pour Sitzia et Wood, trois

dimensions au moins sont à prendre en compte : la capacité

des soignants à créer une relation de soins confortable, les

changements ressentis par les patients et leurs attentes et

enfin, la pertinence des soins par rapport à celles-ci [17].

Or les patients suicidaires se reconnaissent plus de besoins

que les autres patients [14] et sont plus nombreux à con-

sidérer que leurs attentes n’ont pas été remplies par la

prise en charge [4,14], d’où l’importance et la nécessité de

s’intéresser à leur point de vue sur les soins.

Dans le Nord—Pas-de-Calais, l’impact sur les récidives

d’un recontact téléphonique systématique, dans les

semaines suivant une tentative de suicide, a été évalué

dans le cadre de l’étude SYSCALL. Nous ne reprendrons

pas en détail les résultats de cette étude [18], mais nous

intéresserons au vécu des patients face à cette interven-

tion inhabituelle et à leur évaluation de l’impact d’une telle

méthode.

L’étude SYSCALL

SYSCALL [18] est une étude multicentrique randomisée

réalisée dans 13 centres d’urgences du Nord—Pas-de-Calais :

605 patients, se présentant aux urgences après une tenta-

tive de suicide par intoxication médicamenteuse volontaire

et pour qui un psychiatre jugeait qu’une hospitalisation

n’était pas nécessaire, ont été inclus dans l’étude et

randomisés en deux groupes. Les patients du groupe témoin

bénéficiaient de la prise en charge usuelle et n’étaient

joints qu’après 13 mois. Les patients du groupe intervention

étaient recontactés par téléphone soit à un mois soit à trois

mois de leur sortie des urgences. La randomisation était

stratifiée sur le sexe et le pourcentage de multirécidivistes

(plus de quatre tentatives de suicide dans les trois ans

passés). L’objectif principal de l’étude était de mesurer

l’influence d’un recontact téléphonique systématique après

une tentative de suicide sur la récidive précoce. Au cours de

cet entretien téléphonique les investigateurs s’assuraient de

la pertinence des modalités de suivi prévues aux urgences,

de les réajuster si nécessaire, rappelaient les numéros de

téléphone «ressources »et évaluaient l’état psychique du

patient avec la possibilité d’une prise en charge rapide en

cas de souffrance psychique ou de risque suicidaire. Au

13emois de l’étude, une évaluation finale était réalisée pour

l’ensemble de la cohorte au cours de laquelle étaient éval-

ués l’existence de troubles psychiatriques, les données sur

le devenir, les récidives éventuelles et le parcours de soins.

Sur les 605 patients inclus, 312 ont formé le groupe témoin,

147 ont été recontactés à la fin du premier mois et 146 à

la fin du troisième. Le taux de récidives suicidaires dans

l’année suivant le geste suicidaire dans le groupe recontacté

à un mois était significativement plus faible que dans le

groupe témoin (12 % vs 22 % ; p = 0,03), mais non significatif

dans le groupe à trois mois (17 % vs 22 % ; p= 0,27). Ainsi, il

semblait donc qu’un recontact téléphonique systématique,

un mois après une tentative de suicide, ait contribué à

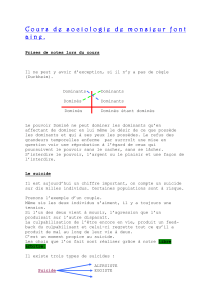

diminuer le risque de récidive suicidaire précoce (Fig. 1).

Objectif

Parce que cette mesure inhabituelle en France, nous parais-

sait intrusive, nous avons voulu connaître le vécu des

patients dans le déroulement de la procédure et l’impact

qu’ils avaient attribué à ce recontact. Dans l’objectif

Figure 1 Description de l’étude SYSCALL avec les résultats significatifs montrant que le recontact téléphonique précoce (à un

mois) diminue significativement le risque de récidive suicidaire à un an en comparaison des autres groupes.

D10 G. Gruat et al.

Tableau 1 Comparaison des patients ayant répondu au questionnaire de vécu subjectif et des patients n’ayant pas répondu.

Questionnaires remplis Oui Non p

n= 254 (%) n= 345 (%)

Multirécidivistes 11,8 7,2 0,056

Recontactés 42,9 26,7 < 0,0001

Femmes 78,7 67,2 0,002

Présence à visite finale de... n= 254 (%) n= 228 (%)

Trouble de l’humeur

Trouble anxieux

Risque suicidaire

35,3

56,4

20,7

23,2

51,2

11

0,009

0,301

0,01

d’évaluer l’acceptation du recontact et de ses modalités,

nous avons proposé aux patients de répondre à un question-

naire de satisfaction.

Patients et méthode

Deux questionnaires distincts ont été élaborés : l’un pour

le groupe témoin, l’autre pour les patients recontac-

tés. Le questionnaire était joint au courrier annonc¸ant le

rendez-vous téléphonique pour l’évaluation finale. Si le

questionnaire n’avait pas été retourné, les patients pou-

vaient y répondre lors de l’évaluation téléphonique finale.

Les deux questionnaires abordaient des questions sur la prise

en charge après leur tentative de suicide, les attentes et les

a priori quant au recontact. Pour les patients recontactés,

nous avons ajouté des questions sur l’impact du recontact

sur leur vie et demandé leur appréciation des modalités du

recontact.

Résultats

Parmi les 482 patients ayant pu être joints à 13 mois, 254 ont

rempli le questionnaire de vécu subjectif (taux de réponses

de 52,7 % sans différence entre les trois groupes) (Tableau 1).

Nous retrouvions chez les répondeurs une surreprésentation

féminine, une plus grande proportion de patients recontac-

tés et une plus grande fréquence de troubles de l’humeur et

de risque suicidaire chez les répondeurs à l’évaluation finale

du 13emois.

Vécu subjectif du recontact

Cent neuf patients recontactés (57 à un mois et 52 à trois

mois) ont donc répondu au questionnaire de vécu subjec-

tif (soit un taux de réponse de 37,2 %). La grande majorité

(78,9 %) d’entre eux considérait le recontact bénéfique. Ils

étaient 40,4 % à considérer qu’il avait eu une influence sur

leur vie et 29,4 % des patients estimaient que le recontact

avait contribué à leur éviter une nouvelle tentative de sui-

cide. Nous ne notions aucune différence significative entre

les deux groupes (Tableau 2).

Modalités du recontact

Parmi les patients recontactés, 94,5 % déclaraient avoir été

bien rec¸us par la personne chargée du recontact et le fait

qu’il ait été effectué par un médecin différent de celui ren-

contré aux urgences n’avait gêné que 8,3 % des patients

même si 20,2 % auraient préféré être recontactés par un

médecin connu. La majorité d’entre eux (54,1 %) consid-

Tableau 2 Vécu subjectif des patients recontactés.

Groupe recontactés M1 M3 (n= 109) Oui (%) Non (%) NSP (%)

Le recontact a-t-il été bénéfique ? 78,9 9,2 11,9

Avez-vous été bien rec¸u(e) par le recontacteur ? 94,5 1,8 3,7

Était-ce une gêne que ce ne soit pas le médecin des Urgences ? 8,3 89,9 1,8

Auriez-vous préféré un contact avec un médecin connu ? 20,2 74,3 5,5

Le téléphone est-il une procédure appropriée ? 54,1 29,4 16,5

Avec 89,5 % proposant comme alternative un contact direct

Le recontact a-t-il eu une influence sur votre vie ? 40,4 49,5 10,1

Le recontact a-t-il permis d’éviter récidive suicidaire ? 29,4 56 14,7

Souhaitiez-vous un recontact plus tôt ? 29,4 45,0 25,7

Souhaitiez-vous un recontact plus tard ? 4,6 52,3 43,1

À l’annonce du recontact, étiez-vous ennuyé(e) ? 14,7 62,4 22,9

À l’annonce du recontact, étiez-vous satisfait(e) ? 76,1 9,2 14,7

Groupe M1 : recontactés à un mois ; groupe M3 : recontactés à trois mois ; NSP : ne se prononce pas.

Vécu subjectif du recontact téléphonique après tentative de suicide D11

Tableau 3 Description des patients en fonction de leur satisfaction par rapport au recontact téléphonique.

Dans votre cas, pensez-vous que le recontact a été bénéfique ? Non(n= 10) (%) Oui(n= 86) (%) p

Recontactés à un mois ou à trois mois

ATCD familiaux de TS 71,4 26,3 0,024

Trouble de l’humeur à la visite finale 55,6 23,8 0,055

Le recontact devrait concerner tout le monde 60 93 0,002

Importance d’un recours téléphonique d’urgence 60 90,7 0,007

Gêne d’un recontact par un médecin inconnu 30 3,5 0,01

Tableau 4 Comparaison du vécu subjectif des primosuicidants et des récidivistes.

Primosuicidants Récidivistes p

Total des répondeurs au 13emois n = 129 n= 125

Jugent positif que les urgences contactent leur médecin 55,8 % 68 % 0,012

Groupe recontact à 1 mois et à 3 mois n = 54 (%) n= 55 (%)

Ressentent un bénéfice du recontact 79,6 78,2 ns

Ressentent un impact positif du recontact 38,9 41,8 ns

Auraient voulu un recontact plus précoce 16,7 41,8 0,013

Groupe témoin (non recontacté) n = 75 (%) n= 70 (%)

Pensent que recontact aurait été bénéfique 48 71,4 0,010

Pensent que recontact aurait entraîné un changement 26,7 41,4 0,015

éraient le téléphone comme la méthode la plus appropriée,

mais l’alternative choisie par 89,5 % des patients non con-

vaincus était la consultation. Enfin, la majorité d’entre eux

(quel que soit le groupe) considéraient le moment du recon-

tact adapté (groupe M1 [61,4 %] vs groupe M3 [80,8 %] ;

p= 0,079) (Tableau 2).

Quelle insatisfaction ?

Dix patients recontactés (cinq du groupe M1 et cinq du

groupe M3) ont déclaré que le recontact ne leur avait

été d’aucun bénéfice. Sur le plan sociodémographique

ou psychopathologique à l’évaluation initiale, aucun élé-

ment n’était caractéristique de cette population, sinon une

fréquence plus importante d’antécédents familiaux de ten-

tatives de suicide. En revanche, ils présentaient une plus

grande fréquence de troubles de l’humeur et de troubles

anxieux, sans qu’il n’y ait de différence statistiquement

significative. Enfin, leur appréciation sur les modalités du

recontact différait selon la satisfaction. Ainsi, la majorité

des patients insatisfaits auraient souhaités être prévenus du

moment du recontact et la moitié d’entre eux ont consid-

éré que le recontact avait été trop tardif, sans pour autant

avoir été gênés par le fait d’être contactés par un nouvel

interlocuteur (Tableau 3).

Le cas des primosuicidants

Cent vingt-neuf patients ont été inclus après un premier

geste suicidaire et 54 d’entre eux ont été recontactés.

Ces patients semblaient avoir moins d’attente par rapport

aux soins puisqu’ils étaient moins nombreux à consid-

érer comme positif le fait de maintenir un lien entre les

urgences et leur médecin traitant, et étaient moins nom-

breux à considérer que le recontact téléphonique aurait

dû concerner tous les patients suicidants. Les primosuici-

dants du groupe témoin (n= 75) semblaient plus sceptiques

sur le recontact que les récidivistes étant moins nom-

breux à considérer qu’il aurait pu induire un changement

ou leur être bénéfique. À l’inverse, s’ils avaient bénéfi-

cié du recontact, ils lui accordaient autant de bénéfice et

lui imputaient autant d’influence que les autres patients

(Tableau 4).

Discussion

L’objectif principal de notre étude était d’évaluer le vécu

des patients face à une procédure thérapeutique inhab-

ituelle en France : le recontact téléphonique systématique

après une tentative de suicide.

Notre premier constat était qu’une très grande majorité

des patients considérait ce recontact bénéfique et la procé-

dure téléphonique adaptée. Un résultat cohérent avec la

littérature qui nous place dans la moyenne de satisfac-

tion des soins psychiatriques ambulatoires classiques [1,10].

Ainsi, malgré notre culture «latine », nous pouvons con-

stater que cette procédure n’a pas déstabilisé les patients.

Par ailleurs, nous ne sommes pas étonnés de constater que

les patients considéraient le contact direct (consultation)

comme une bonne alternative au contact téléphonique.

Soulignons cependant que c’est justement l’échec des

procédures classiques de suivi des patients qui nous a con-

duits à élaborer le recontact téléphonique en raison de

la faible adhésion aux soins post-urgence (puisque seuls

40 % des patients se rendent au rendez-vous de suivi [3]).

Ainsi, le recontact téléphonique ne doit pas être confondu

6

6

7

7

1

/

7

100%