La maladie coronaire chez le patient infecté par le VIH

MISE AU POINT

La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 439 - novembre 2010 | 15

La maladie coronaire

chez le patient infecté par le VIH

Coronary artery disease in HIV-infected patients

F. Boccara*

* Service de cardiologie, CHU de Saint-

Antoine et Inserm UMR_938, univer-

sité Pierre-et-Marie-Curie, Paris.

D

epuis l’avènement d’antirétroviraux très effi-

caces au milieu des années 1990, la morbi-

mortalité des patients infectés par le virus

de l’immunodéficience humaine (VIH) a diminué

de façon spectaculaire dans les pays industrialisés ;

cette infection aiguë potentiellement mortelle est

ainsi devenue une maladie chronique sous anti-

rétroviraux. Dans le même temps, des complications

métaboliques secondaires à ce même traitement,

mais probablement secondaires aussi à l’infection

chronique même contrôlée, sont apparues, et ont

favorisé l’apparition d’événements coronariens aigus

par le biais d’un processus d’athérosclérose accélérée

dont les mécanismes sont encore mal élucidés. Dans

les pays ayant accès au traitement antirétroviral

efficace, nous sommes passés des complications

cardiovasculaires liées à l’état d’immunodépres-

sion (myocardite, péricardite) – qui ont presque

disparues – à des complications liées, au moins en

partie, aux troubles métaboliques, en particulier

glucido-lipidiques, qui favorisent l’athérosclérose

et les événements coronaires aigus (1).

Épidémiologie

Actuellement, 40 millions de personnes dans le

monde sont infectées par le VIH. Le traitement

antirétroviral comporte habituellement 3 molé-

cules : 2 inhibiteurs nucléosidiques de la transcrip-

tase inverse (INTI) associés soit à un inhibiteur de

protéase (IP) soit à un inhibiteur non nucléosidique

de la transcriptase inverse (INNTI).

En France, le nombre de sujets infectés est estimé

à environ 130 000. Les complications cardiovascu-

laires sont devenues la troisième cause de décès et

la quatrième cause d’hospitalisation des patients

infectés par le VIH dans les pays industrialisés,

après les causes liées au sida et celles infectieuses,

carcinologiques et hépatiques (2, 3). On note que

les causes de décès des sujets infectés par le VIH

et des patients immunocompétents sont compa-

rables à celles de la population générale (cancers

et maladies cardiovasculaires), mais surviennent

plus précocement (en moyenne avant 50 ans pour

l’infarctus du myocarde [IDM]).

La population infectée par le VIH est plus à risque

de présenter un IDM que la population générale

(risque multiplié par 2) [4] et elle présente un

surrisque cardiovasculaire lié à plusieurs facteurs.

De nombreuses études ont montré que le risque

cardiovasculaire, mesuré à l’aide d’une équation de

risque, des sujets infectés par le VIH et sous antiré-

troviraux est plus élevé que celui de la population

générale (5-7). Il existe environ 2 fois plus de sujets

infectés par le VIH qui présentent un risque cardio-

vasculaire élevé (risque > 20 %) de présenter un IDM

que dans la population générale. Parallèlement, il a

bien été démontré que, quelle que soit la classe d’âge

– et en particulier dans la population jeune (moins

de 40 ans) –, l’incidence de l’IDM est environ 2 fois

plus élevée dans la population infectée par le VIH

par rapport à la population générale (4, 8).

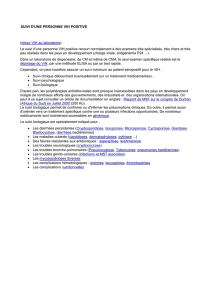

Physiopathologie

Comment peut-on expliquer ce surrisque “épidémio-

logique” ? Tout d’abord, il est certain que le poids

des facteurs de risque dits “traditionnels” est majeur

dans cette population. En particulier, le tabagisme

et la dyslipidémie sont surreprésentés avec une

prévalence de plus de 30 % et 50 % respectivement

(9, 10). D’autre part, la consommation de drogues

illicites, et en particulier de cocaïne, ne doit pas être

sous-estimée car elle est beaucoup plus fréquente

Traitement

antirétroviral

Accélération

de l’athérosclérose

VIH lui-même

Dyslipidémie ( HDL-c, LDL-c, VLDL, TG)

Insulinorésistance

Diminution de l’adiponectine

Hyperactivité du système rénine-angiotensine

Toxicité mitochondriale

Stress oxydant activé

Dysfonction endothéliale

HDL-c

Activation du facteur tissulaire

Hyperactivité immune (lymphocyte T, chimiokines)

Hyperactivité inflammatoire (TNFα, IL-6)

Rôle des co-infections inconnu : Virus hépatites B et C

Facteurs de risque classiques

Tabagisme, drogues illicites, diabète

Figure. Hypothèses physiopathologiques de l’accélération de l’athérosclérose chez le patient infecté par le VIH

sous antirétroviraux

16 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 439 - novembre 2010

Points forts

»

Le syndrome coronaire aigu est plus fréquent et plus précoce (avant 50 ans) chez les sujets VIH+ que

dans la population générale.

»

Le tabagisme est le facteur de risque traditionnel le plus fréquemment rencontré dans cette population.

»

L’utilisation de drogues illicites favorisant l’infarctus du myocarde, en particulier la cocaïne, ne doit

pas être méconnue.

»

Les caractéristiques cliniques et angiographiques de la maladie coronaire diffèrent peu de la population

à âge équivalent.

»

Le pronostic immédiat de la revascularisation coronaire par angioplastie ou pontage aorto-coronaire

est excellent.

»

Le pronostic à moyen terme est marqué par des récidives ischémiques plus fréquentes sans excès de

thrombose de stent.

Mots-clés

Syndrome coronaire

aigu

Virus de

l’immunodéficience

humaine

Athérosclérose

Antirétroviraux

Highlights

»

Acute coronary syndrome is

frequent and premature (before

50 years’old) in HIV-infected

patients compared with the

general population.

»

Tobacco consumption is

the most frequent traditional

vascular risk factors in HIV-

infected population.

»

The use of illicit drugs

particularly cocaine abuse

should be screened.

»

The clinical and angio-

graphic features of coronary

artery disease do not differ

from the general population.

»

The immediate prognosis

of coronary revascularization

(percutaneous coronary inter-

vention or coronary artery

bypass surgery) is excellent.

»

The mid-term prognosis of

acute coronary syndrome is

worse in HIV-infected patients

with increased recurrent

ischemic event without

increased stent thrombosis.

Keywords

Acute coronary syndrome

Human immunodeficiency

virus

Atherosclerosis

Antiretroviral therapy

que dans la population générale (11). Le diabète est

plus fréquent et concerne environ 8 % de la popula-

tion infectée en France (12, 13). Enfin, un syndrome

de lipodystrophie (anomalie de la répartition des

graisses) a été décrit chez les sujets infectés par le

VIH et sous antirétroviraux (14). Sa physiopathologie

reste complexe et mal comprise et fait intervenir

le virus, les antirétroviraux, l’environnement et des

facteurs génétiques (15). Son incidence tend à dimi-

nuer avec les nouveaux antirétroviraux ayant un

faible effet sur le tissu adipeux. En effet, ce syndrome

est lié à une anomalie du tissu adipeux viscérale

et sous-cutanée pouvant participer, comme dans

le syndrome métabolique de la population géné-

rale, à des surrisques cardiovasculaire (risque accru

d’IDM) et métabolique (risque accru de diabète).

Le rôle direct du syndrome de lipodystrophie dans le

surrisque d’IDM reste à démontrer mais les complica-

tions métaboliques fréquemment associées (dyslipi-

démie, insulinorésistance et inflammation) plaident

en faveur d’un facteur favorisant le développement

de l’athérosclérose (13).

D’autres facteurs favorisant le processus athéro-

scléreux et athérothrombotique ont été identifiés.

Ainsi, la présence d’une dysfonction endothéliale

directement liée au traitement antirétroviral, à l’in-

fection et à l’inflammation chronique ainsi que les

troubles de l’hémostase favorisent, en synergie avec

les autres facteurs de risque, la survenue d’événe-

ments cardiovasculaires (figure) [16].

Qu’en est-il de l’effet

du traitement antirétroviral

sur le risque d’IDM ?

Toutes les études s’accordent à montrer que le trai-

tement antirétroviral et, plus précisément, la durée

d’exposition aux IP favorisent le risque d’IDM, en

partie seulement du fait de la dyslipidémie qu’ils

induisent (10, 17, 18). L’étude DAD montre que toute

année d’exposition aux IP augmente le risque d’IDM

de 16 % (RR = 1,16 ; IC

95

: 1,10-1,23) après ajuste-

ment pour les facteurs de risque traditionnels (17).

MISE AU POINT

La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 439 - novembre 2010 | 17

Si l’on ajuste sur les paramètres lipidiques, ce risque

diminue à 10 % par année supplémentaire mais il

reste significatif (RR = 1,10 ; IC95 : 1,04-1,18), ce qui

souligne l’effet direct du traitement par IP. Plus

récemment, la didanosine et l’abacavir (2 INTI) ont

été mis en cause, de façon rétrospective, dans le

surrisque d’IDM, alors même que l’abacavir n’en-

traîne pas de dyslipidémie (19, 20). À partir de la base

française de sujets infectés par le VIH, nous n’avons

pas retrouvé les mêmes résultats concernant l’effet

de l’abacavir (21). En effet, lorsque nous retirons de

l’analyse les sujets toxicomanes (héroïnomanes ou

cocaïnomanes), nous ne retrouvons pas d’association

entre abacavir et risque d’IDM, soulignant là encore

le rôle des drogues illicites dans la survenue des IDM

et les biais des études de cohorte qui ne prennent

pas en compte tous les facteurs confondants.

Enfin, l’étude SMART (22) apporte un argument en

faveur du rôle du virus lui-même ou plutôt de l’im-

munité dans le risque d’IDM. Cette étude compa-

rait 2 attitudes thérapeutiques chez le sujet infecté

par le VIH sous antirétroviraux : soit un traitement

antirétroviral continu ayant comme objectif une

charge virale indétectable, soit un traitement discon-

tinu. Elle a été arrêtée précocement en raison d’un

nombre plus significatif d’événements cardiovas-

culaires (ischémiques et autres), rénaux et hépa-

tiques dans le groupe traitement discontinu, ce qui

souligne le rôle probable de l’infection chronique

et/ou du déficit immunitaire dans la genèse des

événements athérothrombotiques. L’identification

relativement récente d’un surrisque cardiovasculaire

probablement lié à la conjugaison de divers facteurs

de risque, dont le tabagisme et les troubles méta-

boliques (glucido-lipidiques), dans une population

“vieillissante” fait craindre une augmentation de

l’incidence des événements cardiovasculaires, en

particulier coronaires aigus, chez les patients infectés

par le VIH dans les années à venir. Il est donc indis-

pensable que le risque cardiovasculaire de chaque

patient soit évalué avant l’instauration et pendant la

durée du traitement antirétroviral comme au cours

de toute maladie chronique de type inflammatoire.

Diagnostic

Le plus souvent, la maladie coronaire chez le sujet

infecté par le VIH commence par un syndrome

coronaire aigu (SCA) et, en particulier, par un

IDM ST+ (23-28). Cette pathologie représente le

mode d’entrée classique d’un sujet jeune dans la

maladie coronaire, ce qui souligne le rôle majeur

de la rupture de plaques et des phénomènes

athérothrombotiques dans cette population. Plus

rarement, la maladie coronaire est découverte

à l’occasion d’un angor stable, mais la popula-

tion infectée par le VIH vieillit (environ 40 % ont

plus de 50 ans), et ce diagnostic ne doit pas être

sous-estimé, en particulier chez ceux qui cumu-

lent les facteurs de risque. Enfin, la prévalence de

l’ischémie silencieuse (IS) dans cette population a

été peu étudiée. Il semblerait que l’IS soit fréquem-

ment détectée lors d’études électrocardiographiques

(29) et de test de l’épreuve d’effort (30).

Atteinte coronaire

et pronostic

Dans les différentes études (23, 25-27) évaluant le

pronostic de la maladie coronaire chez le patient

infecté par le VIH, on note que ces patients avaient

le plus souvent moins de 50 ans, une durée d’in-

fection et de traitement importante (supérieure à

8 ans) associée à un tabagisme important et une

dyslipidémie induite par les antirétroviraux. En ce

qui concerne l’atteinte coronaire, peu d’études

ont comparé l’aspect angiographique au cours des

syndromes coronariens aigus entre patients infectés

et non infectés par le VIH (23, 26, 27). Dans ces

séries à faible effectif (20 à 50 patients), il semble

que l’atteinte en termes de nombre de vaisseaux

atteints, d’extension et de sévérité de la maladie

coronarienne soit identique dans les 2 populations,

avec une prévalence plus importante de l’atteinte

monotronculaire, ce qui est habituel chez les patients

de moins de 45 ans présentant un IDM. S. Matetzky

et al. (27) ont montré qu’il existait, après un IDM,

plus de risques de récidive ischémique ou de resté-

nose coronaire clinique chez le patient infecté par

le VIH que chez le patient non VIH. De la même

manière, en cas d’angioplastie sans stent, P.Y. Hsue

et al. (26) ont noté que la resténose clinique était

plus fréquente chez le sujet infecté. Dans cette

étude dont l’effectif était faible, cette différence

disparaissait après implantation d’un stent. Notre

groupe a, quant à lui, observé dans une étude rétros-

pective, qu’après angioplastie coronaire pour angor

ou syndrome coronaire aigu, le taux d’événements

cardiovasculaires était identique entre patients

infectés par le VIH et les sujets témoins après un

suivi de 20 mois (23). Dans une étude prospective

longitudinale intitulée étude PACS (Prognosis of

Acute Coronary Syndrome in HIV-infected patients)

réalisée en France, nous montrons également, après

La maladie coronaire chez le patient infecté par le VIH

MISE AU POINT

18 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 439 - novembre 2010

1 an de suivi (le suivi final sera de 3 ans), que les

patients infectés par le VIH présentent plus de réci-

dive de SCA et de revascularisation coronaire urgente

par angioplastie que les sujets non VIH (31). Dans le

même temps, le taux de resténose coronaire clinique

n’était pas plus important dans les 2 groupes, ce qui

illustre un processus athérothrombotique accéléré

chez les patients infectés par le VIH en dehors du

problème de resténose.

Enfin, l’utilisation de stent actif reste discutée. En

effet, aucune étude n’a pu montrer un surrisque de

thrombose aiguë ou tardive dans cette population.

Il semble conseillé chez des patients présentant des

pathologies concomitantes, et en particulier oncolo-

giques, de ne pas utiliser ce type de stent en raison

du risque hémorragique lié à la prise prolongée d’une

double antiagrégation plaquettaire et du risque de

thrombose de stent à l’arrêt inopiné.

Prise en charge

Il existe des recommandations spécifiques nord-

américaines (32), européennes (33) et françaises

(34) pour la prévention primaire de la maladie

coronaire dans la population infectée. Elles ne

sont pas très différentes de celles pour la popula-

tion générale. Elles insistent sur le surrisque des

sujets infectés avec, pour les recommandations

françaises, le rôle indépendant du virus dans le

risque d’IDM ; le VIH est alors considéré comme un

facteur indépendant. Ainsi, tout sujet infecté par le

VIH étant considéré comme un sujet avec déjà un

facteur de risque, l’objectif minimal est d’atteindre

un LDL-c à moins de 1,9 g/l (tableau I). D’autre

part, ces recommandations soulignent le risque

d’interactions médicamenteuses avec les IP – aux

complications potentiellement létales – dont le

cardiologue doit être informé (tableau II).

En ce qui concerne le traitement de la dyslipidémie,

une attention particulière doit être portée chez les

patients infectés par le VIH, car plusieurs statines

sont contre-indiquées en raison de l’interaction

avec le cytochrome P450 3A4 et le traitement

par IP (tableau III). En effet, certaines statines

(simvastatine et atorvastatine) voient leur taux

plasmatique augmenté avec un risque accru de

rhabdomyolyse. Chez les patients infectés par le

VIH, il est donc actuellement conseillé de traiter

une dyslipidémie avec de la pravastatine, de la

fluvastatine ou de la rosuvastatine, qui est plus

puissante. Un essai comparatif récent (rosuvasta-

Tableau II. Interactions potentielles entre antirétroviraux et médicaments cardiologiques.

Molécules Antirétroviraux Commentaires

Molécules métabolisées

par le CYP450 3A4*

Toutes les antiprotéases associées au

ritonavir interagissent

Interaction avec le Bactrim®

Risque d’effets graves ou pou-

vant engager le pronostic vital

Inhibiteurs calciques (IC) Précautions en cas de

coprescription d’antiprotéases et d’IC

Débuter à faible dose

ECG recommandé (intervalle PR)

Antiarythmiques Contre-indication avec le ritonavir :

amiodarone, flécaïne, quinidine et

propafénone

Effets graves ou pouvant

engager le pronostic vital

Warfarine Les antiprotéases associées au rito-

navir entraînent une diminution de la

concentration de warfarine

L’efavirenz et la névirapine

pourraient diminuer l’efficacité

de la warfarine

Contrôle plus fréquent de l’INR

Ajuster la posologie

de la warfarine

Inhibiteurs PDE-5** Les antiprotéases associées au ritona-

vir entraînent une augmentation des

inhibiteurs PDE-5

Débuter à faible dose

* Amiodarone, lidocaïne, quinidine, warfarine, simvastatine, atorvastatine, inhibiteurs calciques, bêta-

bloquants, sildénafil, tacrolimus, ciclosporine.

** Inhibiteurs PDE-5 : Viagra®, Cialis®, Levitra®.

Tableau III. Interactions hypolipémiants et antirétroviraux.

Hypolipémiants Interactions avec un IP Autres interactions avec les antirétroviraux

Statines

Atorvastatine Oui, mais peut être utilisée

à faible dose

Efavirenz diminue l’activité

Simvastatine Oui, contre-indication absolue Efavirenz diminue l’activité

Fluvastatine Non ND

Pravastatine Non Précaution d’emploi avec le darunavir car

risque d’augmentation de l’ASC

L’efavirenz diminue l’activité

Rosuvastatine Non ND

Fibrates

Fénofibrate Non ND

Bézafibrate Non ND

Gemfibrozil Non ND

Ézétimibe Non ND

Acide nicotinique Non ND

ND : non documenté ; IP : inhibiteur de protéase ; ASC : aire sous la courbe.

Tableau I. Recommandations pour la prise en charge du LDL-cholestérol chez le patient infecté

par le VIH (34).

Niveau du risque Facteur de risque (FDR) Objectif de LDL-c

à atteindre

Patients à risque intermédiaire Infection par le VIH

sans aucun autre FDR

LDL-cholestérol < 1,9 g/l

(< 4,9 mmol/l)

Infection par le VIH

avec 1 autre FDR

LDL-cholestérol < 1,6 g/l

(< 4,1 mmol/)

Infection par le VIH

avec au moins 2 autres FDR

LDL-cholestérol < 1,3 g/l

(< 3,4 mmol/l)

Patients à haut risque Infection par le VIH

avec antécédents cardiovasculaires

avérés ou diabète de type 2

à haut risque

LDL-cholestérol < 1,0 g/l

(< 2,6 mmol/l)

MISE AU POINT

La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 439 - novembre 2010 | 19

1. Barbaro G. Cardiovascular manifestations of HIV infection.

Circulation 2002;106:1420-5.

2. Kwong GP, Ghani AC, Rode RA et al. Comparison of the

risks of atherosclerotic events versus death from other causes

associated with antiretroviral use. AIDS 2006;20:1941-50.

3. Lewden C, May T, Rosenthal E et al. Changes in causes

of death among adults infected by HIV between 2000 and

2005: The “Mortalite 2000 and 2005” surveys (ANRS EN19

and Mortavic). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:590-8.

4. Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased

acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk

factors among patients with human immunodeficiency

virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2506-12.

5. Bergersen BM, Sandvik L, Bruun JN, Tonstad S. Elevated

Framingham risk score in HIV-positive patients on highly

active antiretroviral therapy: results from a Norwegian study

of 721 subjects. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2004;23:

625-30.

6. Neumann T, Woiwod T, Neumann A et al. Cardiovas-

cular risk factors and probability for cardiovascular events

in HIV-infected patients - part III: age differences. Eur J Med

Res 2004;9:267-72.

7. Kaplan RC, Kingsley LA, Sharrett AR et al. Ten-year

predicted coronary heart disease risk in HIV-infected men

and women. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:1074-81.

8. Mary-Krause M, Cotte L, Simon A, Partisani M, Costa-

gliola D. Increased risk of myocardial infarction with duration

of protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected men. AIDS

2003;17:2479-86.

9. Friis-Moller N, Weber R, Reiss P et al. Cardiovascular

disease risk factors in HIV patients--association with

antiretroviral therapy. Results from the DAD study. AIDS

2003;17:1179-93.

10. Friis-Moller N, Sabin CA, Weber R et al. Combination

antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction.

N Engl J Med 2003;349:1993-2003.

11. Meng Q, Lima JA, Lai H et al. Coronary artery calcifica-

tion, atherogenic lipid changes, and increased erythrocyte

volume in black injection drug users infected with human

immunodeficiency virus-1 treated with protease inhibitors.

Am Heart J 2002;144:642-8.

12. Capeau J. From lipodystrophy and insulin resistance to

metabolic syndrome: HIV infection, treatment and aging.

Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2007;2:247-52.

13. Grinspoon S. Diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular risk, and

HIV disease. Circulation 2009;119:770-2.

14. Grinspoon S, Carr A. Cardiovascular risk and body-

fat abnormalities in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med

2005;352:48-62.

15. Caron M, Vigouroux C, Bastard JP, Capeau J. Antiretro-

viral-Related Adipocyte Dysfunction and Lipodystrophy in

HIV-Infected Patients: alteration of the PPARgamma-Depen-

dent Pathways. PPAR Res 2009;2009:5071-41.

16. Stein JH. Endothelial function in patients with HIV infec-

tion. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:540-1.

17. Friis-Moller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA et al. Class of antire-

troviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl

J Med 2007;356:1723-35.

18. Worm SW, Friis-Moller N, Bruyand M et al. High preva-

lence of the metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients:

impact of different definitions of the metabolic syndrome.

AIDS 2010;24:427-35.

19. Sabin CA, Worm SW, Weber R et al. Use of nucleoside

reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarc-

tion in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the D:A:D study:

a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet 2008;371:1417-26.

20. Groups SfMoA-RTIDS. Use of nucleoside reverse trans-

criptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-

infected patients. AIDS 2008;22:F17-24.

21. Lang S, Mary-Krause M, Cotte L et al. Impact of specific

NRTI and PI exposure on the risk of myocardial infarction: a

case-control study nested within FHDH ANRS CO4. Archives

on Internal Medicine 2010; sous presse.

22. El-Sadr WM, Lundgren JD, Neaton JD et al. CD4+ count-

guided interruption of antiretroviral treatment. N Engl J

Med 2006;355:2283-96.

23. Boccara F, Teiger E, Cohen A et al. Percutaneous coronary

intervention in HIV infected patients: immediate results and

long term prognosis. Heart 2006;92:543-4.

24. Ambrose JA, Gould RB, Kurian DC et al. Frequency

of and outcome of acute coronary syndromes in patients

with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Cardiol

2003;92:301-3.

25. Escaut L, Monsuez JJ, Chironi G et al. Coronary artery

disease in HIV infected patients. Intensive Care Med

2003;29:969-73.

26. Hsue PY, Giri K, Erickson S et al. Clinical features of

acute coronary syndromes in patients with human immu-

nodeficiency virus infection. Circulation 2004;109:316-9.

27. Matetzky S, Domingo M, Kar S et al. Acute myocar-

dial infarction in human immunodeficiency virus-infected

patients. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:457-60.

28. Varriale P, Saravi G, Hernandez E, Carbon F. Acute

myocardial infarction in patients infected with human

immunodeficiency virus. Am Heart J 2004;147:55-9.

29. Carr A, Grund B, Neuhaus J et al. Asymptomatic myocar-

dial ischaemia in HIV-infected adults. AIDS 2008;22:257-67.

30. Duong M, Cottin Y, Piroth L et al. Exercise stress testing

for detection of silent myocardial ischemia in human immu-

nodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving antiretroviral

therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2002;34:523-8.

31. Boccara F, Mary-Krause M, Teiger E et al. Acute coronary

syndrome in HIV-infected patients: characteristics and 1-year

prognosis. Eur Heart J 2010; sous presse.

32. Dube MP, Stein JH, Aberg JA et al. Guidelines for the

evaluation and management of dyslipidemia in human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults receiving

antiretroviral therapy: recommendations of the HIV Medical

Association of the Infectious Disease Society of America

and the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis

2003;37:613-27.

33. European AIDS Clinical Society. Guidelines 2009.

Prevention and management of non-infectious co-morbi-

dities in HIV. www.europeanaidsclinicalsociety.org/Guide-

lines2009/G2_pReferences.htm

34. Yeni P. Prise en charge des personnes infectées par le

VIH. Recommandations du groupe d’experts. Complica-

tions associées au VIH et aux traitements antirétroviraux.

Chapitre 7. Rapport 2008 sous la direction du Pr P. Yeni.

Paris : Ministère de la Santé, Éditions Médecine-Sciences

Flammarion 2008.

35. Aslangul E, Assoumou L, Bittar R et al. Rosuvastatin

versus pravastatin in dyslipidemic HIV-1-infected patients

receiving protease inhibitors: a randomized trial. AIDS

2010;24:77-83.

36. Negredo E, Molto J, Puig J et al. Ezetimibe, a promising

lipid-lowering agent for the treatment of dyslipidaemia in

HIV-infected patients with poor response to statins. AIDS

2006;20:2159-64.

37. Bennett MT, Johns KW, Bondy GP. Ezetimibe is effective

when added to maximally tolerated lipid lowering therapy

in patients with HIV. Lipids Health Dis 2007;6:15.

Références bibliographiques

tine 10 mg/j versus pravastatine 40 mg/j) mené en

France a montré une supériorité quasiment double

de la rosuvastatine sur la baisse du LDL-c chez le

sujet VIH sous IP comprenant le ritonavir (35).

L’atorvastatine peut être utilisée à sa dose la plus

faible (10 mg/j) avec précaution (dosage de créatine

phosphokinase rapproché). L’ézétimibe peut être

associé à une statine en cas d’échec d’atteinte des

objectifs sous statine ou de mauvaise tolérance

d’une dose croissante de statine. Son efficacité et

sa bonne tolérance ont été démontrées dans cette

population (36, 37). La place des fibrates n’est pas

remise en question en cas d’hypertriglycéridémie

menaçante pour diminuer le risque de pancréatite

aiguë. Il est nécessaire d’arrêter la consommation

de tabac, car l’association avec les IP semble être

un cocktail explosif, d’autant plus qu’une dyslipi-

démie y est associée.

Conclusion

Le risque de présenter un IDM est plus important

dans la population infectée par le VIH que dans la

population générale en raison de facteurs de risque

vasculaire prépondérants mais aussi en raison de

l’infection chronique par le VIH, des antirétroviraux

et des complications métaboliques secondaires à ces

mêmes traitements. La prise en charge du SCA est la

même que dans la population générale. Une colla-

boration étroite entre le médecin prenant en charge

le patient infecté par le VIH et le cardiologue doit

être menée pour diminuer ce surrisque cardiovas-

culaire, tant en prévention primaire que secondaire.

Il reste à démontrer qu’une attitude agressive en

termes de réduction des facteurs de risque permet,

dans cette population, d’améliorer à long terme la

morbi-mortalité cardiovasculaire. ■

1

/

5

100%