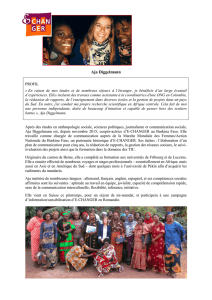

Guide d`Apprentissage en Adja

Guide d’Apprentissage en Adja

Eric A Morley

avec

KANTE Gnonna

29 juillet 2009

Table des mati`eres

Introduction v

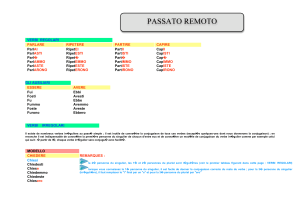

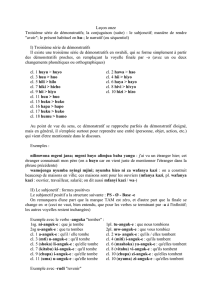

L’Orthographe ix

1 Les Salutations 1

1.1 LesSalutations ............................ 1

1.2 Grammaire/Structure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.2.1 Les pronoms personnels sujets : . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.2.2 Verbes- la forme nue . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

1.2.3 Questions oui/non . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

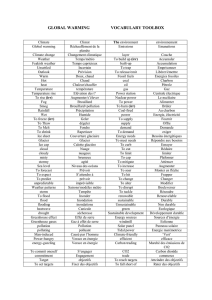

1.3 Vocabulaire .............................. 4

1.4 Exercices ............................... 5

2 La Ville 6

2.1 Dialogue : Fini. . . ........................... 6

2.2 Grammaire .............................. 6

2.2.1 La Forme Progressive . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

2.2.2 Les verbes l`e,y`ı et s´o .................... 7

2.2.3 La question fini ‘o`u ?’ et la particule `O ........... 8

2.3 Vocabulaire .............................. 9

2.4 Exercices ............................... 9

3 La Nourriture 11

3.1 Grammaire .............................. 11

3.1.1 ´

A,Dans.............................. 11

3.2 Vocabulaire .............................. 11

3.3 Exercices ............................... 12

4 Au March´e 14

4.1 LesNombres ............................. 14

4.2 Grammaire .............................. 16

4.2.1 Combien... .......................... 16

4.2.2 La particule a......................... 16

i

ii TABLE DES MATI `

ERES

4.3 Dialogue :

Kojo Yi Afi ME............................ 17

4.4 Exercices ............................... 17

5 Un Voyage 18

5.1 Dialogue :

Nayi... ................................ 18

5.2 Grammaire .............................. 18

5.2.1 EsO............................... 18

5.2.2 Koão ............................. 19

5.2.3 Nyi .............................. 19

5.2.4 Mˇı ............................... 20

5.3 Vocabulaire .............................. 21

5.4 Exercices ............................... 21

6 Retour du Voyage 22

6.1 Dialogue: .............................. 22

6.2 Grammaire .............................. 22

6.2.1 Lespronoms ......................... 22

6.2.2 N´egation ........................... 23

6.2.3 Pourfaire............................. 23

6.3 Vocabulaire .............................. 24

6.4 Exercices ............................... 25

7 La Sant´e 26

7.1 Grammaire .............................. 26

7.1.1 Les Pronoms Objets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

7.1.2 Comment on decrit. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27

7.2 Vocabulaire .............................. 28

7.3 Exercices ............................... 29

8`

A l’´

Ecole 30

8.1 Dialogue................................ 30

8.2 Grammaire .............................. 30

8.2.1 Enu .............................. 30

8.2.2 Les Actions Qui Se Passent Plusieurs Fois - nO...... 31

8.2.3 LePluriel........................... 32

8.2.4 Les Objets Indirects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

8.3 Vocabulaire .............................. 33

8.4 Exercices ............................... 33

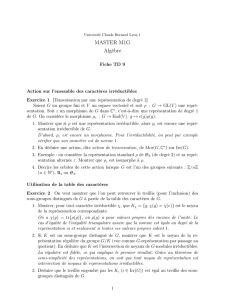

9 Une Formation du Moringa 35

9.1 LaFormation............................. 35

9.2 Grammaire .............................. 35

9.2.1 Ausujetde... ........................ 35

9.2.2 Koãoparti2 ......................... 36

TABLE DES MATI `

ERES iii

9.2.3 Les Participes Pass´es . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

9.2.4 Si................................. 36

9.3 Vocabulaire .............................. 37

9.4 Exercices ............................... 37

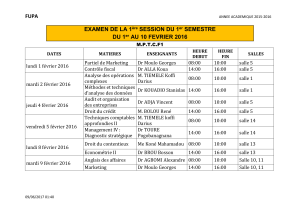

10 Une Formation du SIDA 38

10.1LaFormation............................. 38

10.2Grammaire .............................. 38

10.2.1 Posession ........................... 38

10.2.2 N´egation ........................... 38

10.2.3 lO................................ 39

10.2.4 ão-Devoir .......................... 39

10.3Vocabulaire .............................. 39

10.4Exercices ............................... 39

11 Les Invit´es 40

11.1 Dialogue : Dradrado ......................... 40

11.2Grammaire .............................. 41

11.2.1 L’imperatif .......................... 41

11.3Vocabulaire .............................. 41

11.4Exercices ............................... 41

12 La Nutrition 42

12.1Dialogue................................ 42

12.2Grammaire .............................. 43

12.2.1 Ci yi, Ci wo .......................... 43

12.2.2 sha ‘chaque’.......................... 43

12.2.3 ão............................... 43

12.2.4 Les Nombres Ordinals . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

12.3Vocabulaire .............................. 44

12.4Exercices ............................... 44

13 Le Paludisme 46

13.1Texte ................................. 46

13.2Grammaire .............................. 46

13.2.1 Si...(2) ............................ 46

13.2.2 LesGerunds ......................... 47

13.2.3 mO............................... 47

13.3Vocabulaire .............................. 48

13.4Exercices ............................... 48

14 Mud Stoves 49

14.1Text .................................. 49

14.2 Sentence by Sentence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

14.2.1 Ny`ı m´ı z´an nO ã`a nO´en´u l`e m´ı wo `axw`e m`E wo `O ? . . . . 52

14.2.2 L´e w`o m`E nO`ad`o l`e `el´E `O ?.................. 52

iv TABLE DES MATI `

ERES

14.2.3 `

Ad`o c`ı wo m´ı gb´e z´an nOl`e `el´E`O ?.............. 52

14.2.4 `

Ad`o c`ı wo m´ı gb´e z´an nO `O ?................. 52

14.2.5 Ny`ı w`o d´o nO`ad`o m`E `O ?................... 53

14.2.6 Ny`ı w`o a z´an a m`E `ad`o y´oy´u `O ? .............. 53

14.2.7 L´e w`o a ny`a `ek`O ciyi m´ı a s´o a m`E`ad`o y´oy´u `O ? ...... 54

14.2.8 Ny`ı taão m`ı k´O nO`ek`O s´axw´e ã´o m`E `O ?........... 55

14.2.9 L´e w`o ny´a nOm´O `ek`Ony`any`a l´O ny´O `O ? ........... 55

14.2.10 Ny`ı t`aã`o m`ı w´u `esh`ı `ez`e l´O `O ?................ 57

14.2.11 L´e w`o a s`O `ad`o l´O d´o `O ? ................... 58

14.2.12 L´e m`ı a kp´O ´en´u n´O `ad`o l´O `O ? ................ 59

14.2.13 Vy´E `O, l´e m`ı a ny´a m´O emOl´O ny´ı `al`Ovi ã´ek`a `O ? ...... 59

14.2.14 L´e w`o s`o nOn`ak`ed´ox´u `O ? .................. 60

14.2.15 Ny`On`a c`ıy`ı l`e `ad`o y´oy´u m`E `O ?................ 60

Appendix 61

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

38

38

39

39

40

40

41

41

42

42

43

43

44

44

45

45

46

46

47

47

48

48

49

49

50

50

51

51

52

52

53

53

54

54

55

55

56

56

57

57

58

58

59

59

60

60

61

61

62

62

63

63

64

64

65

65

66

66

67

67

68

68

69

69

70

70

71

71

72

72

73

73

74

74

75

75

76

76

77

77

78

78

1

/

78

100%