L’ Nouvelles cibles et stratégies thérapeutiques dans l’insuffisance

MISE AU POINT

10 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 463 - mars 2013

Nouvelles cibles

et stratégies thérapeutiques

dans l’insuffisance

cardiaque aiguë

New therapeutic targets and strategies in acute

heart failure

E. Gayat*, A. Mebazaa*

* Biomarqueurs et maladies

cardiaques, UMR 942, Inserm, Paris ;

département d’anesthésie-réanima-

tion, hôpital Lariboisière et université

Paris-Diderot, Paris.

L’

insuffisance cardiaque aiguë (ICA) est un

syndrome dont la définition a récemment

été revue par les sociétés savantes. En

effet, des études épidémiologiques récentes, tant

aux États-Unis (Acute Decompensated HEart failure

national REgistry [ADHERE]) qu’en Europe (étude

EuroHeart) ou en France (Étude française sur l'insuf-

fisance cardiaque aiguë [EFICA]), ont apporté un

jour nouveau sur cette entité nosologique. Ainsi,

on distingue dorénavant plusieurs pathologies, bien

individualisées, formant ensemble le “syndrome des

insuffisances cardiaques aiguës”.

La Société européenne de cardiologie (ESC) et la

Société européenne de réanimation (ESICM) se sont

emparées des résultats récemment parus dans ces

études épidémiologiques pour officialiser les défi-

nitions du syndrome des ICA (1). Ces définitions

devront donc être utilisées dans notre pratique

quotidienne ainsi que lors du choix des critères

d’inclusion des prochaines études sur l’ICA.

La prise en charge d’un épisode d’ICA repose sur

l’association de traitements médicamenteux et de

traitements non médicamenteux, en particulier

la ventilation non invasive. Cette mise au point

concerne les nouveautés dans la prise en charge

médicamenteuse d’un épisode d’ICA.

Les définitions actuelles du

syndrome des insuffisances

cardiaques aiguës

Outre l’ESC et l’ESICM, ces définitions ont été adoptées

par les 2 grandes agences que sont la Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) des États-Unis et son équivalent

européen, l’Agence européenne des médicaments

(EMA). Ainsi, le syndrome des ICA est défini par l’appa-

Tableau. Classification (par ordre décroissant de fréquence), fondée sur la présentation clinique,

du syndrome des insuffisances cardiaques aiguës.

Insuffisance cardiaque aiguë

hypertensive

Les signes et symptômes de l’insuffisance cardiaque

sont accompagnés d’une pression artérielle élevée

et d’une fonction ventriculaire systolique gauche préservée

avec une radio du thorax compatible avec un œdème

pulmonaire ; associée de râles crépitants à l’auscultation

pulmonaire et d’une saturation artérielle en oxygène

<90 % à l’air ambiant.

Insuffisance cardiaque chronique

décompensée

Le patient a les signes et les symptômes d’insuffisance

cardiaque aiguë (dyspnée, oligurie) sans signe de choc car-

diogénique, d’œdème pulmonaire ni de crise hypertensive ;

il a été hospitalisé auparavant pour un épisode similaire.

Choc cardiogénique Le choc cardiogénique est défini comme une hypo-

perfusion liée à l’insuffisance cardiaque aiguë malgré

la correction de la précharge. Le choc cardiogénique est

habituellement caractérisé par une pression artérielle

systolique < 90mmHg ou une baisse de la pression

artérielle moyenne de plus de 30mmHg par rapport

à la pression habituelle et/ou d’un débit urinaire inférieur

à 0,5ml/kg/h et d’une fréquence cardiaque supérieure

à60 bats/min. Ceci peut se faire avec ou en l’absence

decongestion ventriculaire droite ou gauche.

Insuffisance cardiaque droite Un bas débit cardiaque, des jugulaires turgescentes,

unfoie volumineux et une hypotension artérielle.

Insuffisance cardiaque à haut

débit cardiaque

Débit cardiaque élevé ; fréquence cardiaque élevée ;

extrémités chaudes ; congestion pulmonaire ; parfois, lors

de l’état de choc septique, la pression artérielle est basse.

La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 463 - mars 2013 | 11

Points forts

»

L’agent optimal pour le traitement de l’insuffisance cardiaque décompensée serait celui qui ferait

baisser les pressions de remplissage ventriculaire, améliorerait les symptômes cliniques et la fonction

rénale, préserverait le tissu myocardique, réduirait la concentration plasmatique des neurohormones et

n’entraînerait pas d’arythmie ni d’hypotension symptomatique.

»

Parmi les médicaments disponibles dans l’insuffisance cardiaque aiguë, les vasodilatateurs sont ceux

qui répondent le mieux au cahier des charges d’un médicament idéal.

»

Les indications des diurétiques doivent être plus limitées et, surtout, les doses plus faibles que par le passé.

»

Le recours aux agents inotropes doit être exceptionnel et uniquement motivé par la présence de signes

d’hypoperfusion (par exemple : oligurie, marbrures) avec ou sans hypotension artérielle et avec ou sans

œdème pulmonaire réfractaire aux diurétiques et aux vasodilatateurs.

Mots-clés

Insuffisance cardiaque

aiguë

Inotrope

Vasodilatateur

Diurétique

Ventilation non

invasive

Highlights

»

The ideal drug to treat acute

heart failure (AHF) patients

should decrease left ventricular

filling pressure, improve symp-

toms, renal function, coronary

perfusion and decrease level of

natriuretic peptides.

»

Among the medications

commonly used in AHF patients,

vasodilatators present the

optimal performance.

»

Indications and dose of

diuretics should be reduced ;

1mg/kg as a bolus should be

the maximum bolus dose at

admission.

»

Catecholamines should be

avoided as much as possible;

the only indication is systemic

hypoperfusion despite an

optimal management.

Keywords

Acute heart failure

Inotrope

Vasodilatator

Diuretic

Non-invasive ventilation

rition rapide ou progressive de signes et symptômes

d’insuffisance cardiaque résultant en hospitalisations

ou consultations non planifiées, chez un cardiologue

ou aux urgences. Le syndrome des ICA est dû soit à la

décompensation d’une insuffisance cardiaque chro-

nique, soit à la survenue d’une insuffisance cardiaque

sur un cœur probablement sain (ou de novo), comme

lors de l’infarctus du myocarde. Il est important de

différencier les insuffisances cardiaques chroniques

décompensées et les ICA sur cœur sain, car la réponse

physiologique sera beaucoup plus prononcée dans le

cas d’une ICA sur cœur sain. De plus, l’ICA sur cœur

sain va se produire chez un patient qui ne prend pas

de médicament cardiovasculaire de façon prolongée

(il y a donc peu d’interactions avec les médicaments

administrés lors de l’ICA). L’ICA de novo a également

une volémie globale qui est normale ou basse par

rapport à l’insuffisance cardiaque chronique décom-

pensée, qui est plutôt en normo- ou hypervolémie.

Le tableau décrit, à partir de signes cliniques, les 5

présentations cliniques formant le syndrome des ICA.

Elles doivent être connues de tous. Notez qu’elles

n’ont pas toutes la même fréquence.

Nouveautés dans la stratégie

de prise en charge

et le traitement

médicamenteux de l’ICA

Le but à atteindre dans le traitement de l’ICA

est d’améliorer rapidement la symptomatologie

du patient admis en urgence et de maintenir son

pronostic à long terme. L’épisode d’ICA et les médi-

caments utilisés ne devraient, idéalement, pas dété-

riorer la survie de ces patients.

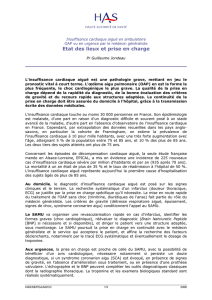

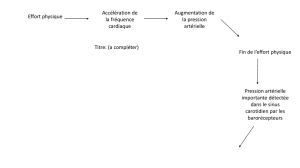

La figure 1, p. 12 reprend les grandes lignes de la

prise en charge d’un patient présentant un épisode

d’ICA selon les recommandations de 2008 conjointes

de l’ESC et de l’ESICM (1).

Les patients doivent bénéficier précocement d’un

monitoring, initialement non invasif, de la pression

artérielle, de la fréquence cardiaque et de la satu-

ration en oxygène. Le bilan minimal, nécessaire à

l’évaluation des patients, comporte un bilan bio-

logique (NFS, ionogramme sanguin avec urémie et

créatininémie, BNP ou NT-proBNP, troponine), un

électrocardiogramme et une radiographie pulmo-

naire. Une évaluation échocardiographique devrait

être effectuée rapidement (2).

Ventilation non invasive

La ventilation non invasive est indiquée en cas de

décompensation cardiaque aiguë avec œdème

pulmonaire. Les facteurs prédictifs d’un échec de

la ventilation non invasive, nécessitant l’intuba-

tion orotrachéale, sont une acidose sévère avec un

pH inférieur à 7,25, une hypercapnie, un syndrome

coronaire aigu, une hypotension artérielle et une

dysfonction ventriculaire gauche sévère (3). La venti-

lation non invasive augmente l’index cardiaque et

diminue le volume télédiastolique du ventricule

gauche chez les patients atteints d’une dysfonc-

tion systolique du ventricule gauche (2), diminue

la postcharge ventriculaire gauche, améliore la

mécanique ventilatoire en augmentant la capacité

résiduelle fonctionnelle, diminue les résistances des

voies aériennes et diminue le travail respiratoire (4).

Plus d’une vingtaine d’études ont comparé les béné-

fices de la ventilation non invasive (CPAP [Continuous

Positive Airway Pressure] ou BiPAP [Bilevel Positive

Airway Pressure]) et du traitement standard. Il en

ressort que la ventilation non invasive, quel qu’en

soit le type, diminue le recours à la ventilation

mécanique et la mortalité (5-7). Plus récemment,

une étude multicentrique randomisée comprenant

1 069 patients a comparé 3 types de prise en charge :

traitement conventionnel avec oxygénothérapie

simple, traitement conventionnel avec CPAP et

traitement conventionnel avec aide inspiratoire et

pression expiratoire positive. Le critère de jugement

principal était la mortalité, qui était similaire que

les patients aient ou non reçu une ventilation non

invasive (8).

Cela étant, les résultats de cette étude sont contro-

versés et n’ont pas à ce jour remis en cause la place de

la ventilation non invasive dans cette pathologie (1).

Pourtant, dans le registre ALARM-HF (Acute Heart

Failure Global Registry of Standard Treatment), seuls

9,6 % des patients bénéficiaient d’une ventilation

non invasive, et 16 % étaient finalement intubés (9).

Nouvelles cibles etstratégies thérapeutiques dansl’insuffisance cardiaque aiguë

MISE AU POINT

Figure 1. Prise en charge initiale d’un épisode d’insuffisance cardiaque aiguë selon les

recommandations de 2008 de l’ESC et de l’ESICM.

Traitement symptomatique

immédiat

Traitement médical,

diurétique/vasodilatateur

Augmentation de la fiO2,

envisager CPAP/VNI/VM

Traitement antiarythmique,

électroentraînement,

électroconversion

Patient agité ou

douloureux

Rythme cardiaque normal

et sinusal

Œdème pulmonaire

Analgésie, sédation

Oui

Oui

Oui

Non

SpO2 < 95 %

VNI : ventilation non invasive.

12 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 463 - mars 2013

Les agents médicamenteux

L’agent optimal pour le traitement de l’insuffi-

sance cardiaque décompensée serait celui qui ferait

baisser les pressions de remplissage ventriculaire,

améliorerait les symptômes cliniques et la fonction

rénale, préserverait le tissu myocardique, réduirait

la concentration plasmatique des neurohormones

et n’entraînerait pas d’arythmie ni d’hypotension

symptomatique. En fait, à l’heure actuelle, aucun

agent ne réunit toutes ces caractéristiques. La réalité

est que l’épisode d’ICA peut entraîner des dégâts

myocardiques et peut altérer ou aggraver la fonc-

tion d’autres organes tels que le rein. Les médica-

ments utilisés lors de l’épisode d’ICA sont, eux aussi,

potentiellement délétères sur le cœur et les autres

organes vitaux.

◆Vasodilatateurs

Parmi les médicaments disponibles dans l’ICA, les

vasodilatateurs sont ceux qui répondent le mieux au

cahier des charges d’un médicament idéal. Ils doivent

donc être essayés en première intention dans l’ICA

quand la pression artérielle est élevée : ICA hyperten-

sive et IC chronique décompensée avec une pression

artérielle systolique élevée (tableau). Des données

récentes semblent indiquer une amélioration de

la survie associée à l’utilisation des médicaments

vasodilatateurs dans l’ICA (10).

Les dérivés nitrés sont recommandés dans l’œdème

aigu pulmonaire (OAP) cardiogénique dès que la

pression artérielle systolique (PAS) est supérieure

à 110 mmHg. Ils sont généralement administrés

en intraveineuse à la seringue électrique. Toute-

fois, dans le cadre de l’urgence chez un sujet en

OAP cardiogénique, notamment au domicile, la

forme sublinguale peut permettre de diminuer de

manière importante la dyspnée et de passer un

cap en attendant le transport du patient en soins

intensifs. La trinitrine diminue la PAS, diminue les

pressions de remplissage des ventricules droit et

gauche (VD et VG). Des données récentes montrent

que les dérivés nitrés peuvent être utilisés chez les

patients en ICA dont la PAS est proche de 100 mmHg

(figure 2) [10]. Il semble en effet que ce soit dans

les formes d’ICA avec une PAS normale ou proche

de 100 mmHg que l’administration de dérivés nitrés

est le plus bénéfique en termes d’amélioration de la

survie ; cela demande à être confirmé par des études

prospectives.

◆Diurétiques

Les indications des diurétiques doivent être plus

limitées et, surtout, les doses plus faibles que par

le passé. Dans l’ICA hypertensive, première cause

d’OAP en France et dans le monde, il n’y a pas

d’hypervolémie préalable, ou peu : un traitement

diurétique trop poussé (> 1 mg/kg) peut vite dépasser

son but et entraîner une hypovolémie. Il est préfé-

rable de privilégier les vasodilatateurs pour améliorer

rapidement la symptomatologie des patients. De

même, une décompensation de la cardiopathie ne

signifie pas obligatoirement hypervolémie.

En revanche, pour un patient en insuffisance

cardiaque chronique décompensée, dyspnéique, mal

suivi et clairement en hypervolémie, les diurétiques

sont indiqués, mais à des doses moindres qu’aupa-

ravant : bolus de 40 mg i.v.d., avec un maximum de

100 mg i.v. les 6 premières heures et de 240 mg les

24 premières heures.

De façon globale, nous avons récemment montré

que la dose initiale de diurétique doit être inférieure

à 80 mg (11).

◆Inotropes positifs

Le recours aux agents inotropes doit être excep-

tionnel et uniquement motivé par la présence de

signes d’hypoperfusion (par exemple : oligurie,

marbrures) avec ou sans hypotension artérielle et

avec ou sans œdème pulmonaire réfractaire aux

diurétiques et aux vasodilatateurs.

L’utilisation des inotropes doit être très prudente,

vu qu’ils entraînent une augmentation de la concen-

tration cellulaire du calcium et de la consommation

myocardique en oxygène (12). Le bénéfice de ces

MISE AU POINT

Figure 2. Effets des vasodilatateurs sur la mortalité intrahospitalière dans l’ICA en fonction de la pression artérielle

à l’admission : données issues du registre ALARM (d’après [10], avec autorisation).

PAS < 100 mmHg

PAS 120-159 mmHg PAS > 160 mmHg

PAS 100-119 mmHg

Jours

Jours Jours

Jours

Mortalité intrahospitalièreMortalité intrahospitalière

Mortalité intrahospitalière Mortalité intrahospitalière

Diurétique i.v. seul

Diurétique i.v. + vasodilatateur i.v.

Diurétique i.v. seul

Diurétique i.v. + vasodilatateur i.v.

Diurétique i.v. seul

Diurétique i.v. + vasodilatateur i.v.

Diurétique i.v. seul

Diurétique i.v. + vasodilatateur i.v.

HR = 0,53 (0,35-0,81)

HR = 1,13 (0,62-2,06) HR = 1,39 (0,62-3,08)

HR = 0,68 (0,37-1,25)

0,4

0,4 0,4

0,4

0,3

0,3 0,3

0,3

0,2

0,2 0,2

0,2

0,1

0,1 0,1

0,1

0,0

0,0 0,0

0,0

0

0 0

05

5 5

510

10 10

1015

15 15

1520

20 20

2025

25 25

2530

30 30

30

La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 463 - mars 2013 | 13

agents sur la contractilité myocardique doit être mis

en balance avec ces 2 effets indésirables, puisqu’ils

peuvent être à l’origine de troubles du rythme,

d’une part, et d’une ischémie myocardique dans

les insuffisances cardiaques d’origine ischémique,

d’autre part (13). Le rapport bénéfice/risque n’est

pas le même pour tous les inotropes. Ceux dont

l’action passe par la stimulation des récepteurs

β1-adrénergiques avec une augmentation de la

concentration du calcium induisent probablement

des risques iatrogènes plus importants (14).

Un effet potentiellement délétère des inotropes dans

l’ICA a été mis en évidence, en particulier pour les

catécholamines (10).

Jusqu’à maintenant, le médicament inotrope le

plus utilisé était la dobutamine. Plus récemment,

2 classes médicamenteuses ont été développées :

les inhibiteurs des phosphodiestérases (milrinone et

énoximone) et les sensibilisateurs calciques (lévo-

simendan).

La milrinone et l’énoximone inhibent sélective-

ment la phosphodiestérase III, l’enzyme impliquée

dans la dégradation de l’adénosine monophos-

phate cyclique en AMP au niveau des cardiomyo-

cytes. Aux doses usuelles, ils ont un effet inotrope

et vasodilatateur périphérique qui entraîne une

augmentation du débit cardiaque et du volume

d’éjection systolique, une baisse de la pression

artérielle pulmonaire d’occlusion (PAPO) ainsi que

des résistances systémiques et pulmonaires (15).

Ces inotropes gardent leurs effets même chez les

patients traités par des bêtabloquants (16). Il ne

semble pas y avoir d’échappement thérapeutique

à moyen terme comme avec la dobutamine.

L’action du lévosimendan passe par une sensibilisa-

tion des protéines contractiles au calcium respon-

sable d’un effet inotrope positif et une ouverture

des canaux potassiques entraînant une vasodila-

tation périphérique avec baisse de la postcharge.

Le lévosimendan est indiqué chez les patients en

Nouvelles cibles etstratégies thérapeutiques dansl’insuffisance cardiaque aiguë

MISE AU POINT

14 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 463 - mars 2013

bas débit cardiaque consécutif à une dysfonction

systolique et non accompagné d’une hypotension

importante. L’administration du lévosimendan chez

les patients en insuffisance cardiaque décompensée

est associée à une augmentation du débit cardiaque

et du volume d’éjection systolique, une baisse de la

pression artérielle pulmonaire d’occlusion ainsi que

des résistances systémiques et pulmonaires avec

une légère augmentation de la fréquence cardiaque

et une baisse de la pression artérielle (17-19).

La place respective des différents inotropes dispo-

nibles n’est pas clairement établie. On peut toutefois

privilégier l’utilisation de la dobutamine chez les

patients non préalablement traités par bêtablo-

quants, tandis que le lévosimendan ou les inhibiteurs

de la phosphodiestérase III sont à utiliser en priorité

chez des patients bêtabloqués.

Conclusion

La stratégie de prise en charge de l’insuffisance

cardiaque repose sur l’association de traitements

médicamenteux et non médicamenteux (en particu-

lier la ventilation non invasive) chez un patient moni-

toré et surveillé étroitement. Le traitement de l’ICA

doit s’appuyer sur un interrogatoire et un examen

clinique minutieux qui permettront de classer le

patient dans une des 5 présentations cliniques

décrites dans le tableau. Le traitement adapté à la

présentation clinique sera instauré rapidement. Le

traitement médicamenteux de première intention

est l’administration de vasodilatateurs, alors que

la place et les doses des diurétiques doivent être

moins importantes que par le passé. L’usage des

catécholamines doit demeurer exceptionnel. ■

1. Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G et al. ESC guide-

lines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic

heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and

treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the

European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collabora-

tion with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA)

and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care

Medicine (ESICM). Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10(10):933-89.

2. Bendjelid K, Schutz N, Suter PM et al. Does continuous

positive airway pressure by face mask improve patients with

acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema due to left ventricular

diastolic dysfunction? Chest 2005;127(3):1053-8.

3. Masip J, Paez J, Merino M et al. Risk factors for intubation

as a guide for noninvasive ventilation in patients with severe

acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Intensive Care Med

2003;29(11):1921-8.

4. L’Her E, Jaffrelot M. Faut-il encore mettre en route une

ventilation non invasive en cas de détresse respiratoire

sur un œdème pulmonaire cardiogénique ? Reanimation

2009;18:720-5.

5. Masip J, Roque M, Sanchez B, Fernandez R, Subirana M,

Exposito JA. Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic

pulmonary edema: systematic review and meta-analysis.

JAMA 2005;294(24):3124-30.

6. Peter JV, Moran JL, Phillips-Hughes J, Graham P,

Bersten AD. Effect of non-invasive positive pressure

ventilation (NIPPV) on mortality in patients with acute

cardiogenic pulmonary oedema: a meta-analysis. Lancet

2006;367(9517):1155-63.

7. Winck JC, Azevedo LF, Costa-Pereira A, Antonelli M,

Wyatt JC. Efficacy and safety of non-invasive ventilation

in the treatment of acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema – a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2006;10(2):

R69.

8. Gray A, Goodacre S, Newby DE, Masson M, Sampson

F, Nicholl J. Noninvasive ventilation in acute cardiogenic

pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med 2008;359(2):142-51.

9. Follath F, Yilmaz MB, Delgado JF et al. Clinical presenta-

tion, management and outcomes in the Acute Heart Failure

Global Survey of Standard Treatment (ALARM-HF). Intensive

Care Med 2011;37(4):619-26.

10. Mebazaa A, Parissis J, Porcher R et al. Short-term

survival by treatment among patients hospitalized with

acute heart failure: the global ALARM-HF registry using

propensity scoring methods. Intensive Care Med 2011;37(2):

290-301.

11. Yilmaz MB, Gayat E, Salem R et al. Impact of diuretic

dosing on mortality in acute heart failure using a propensity-

matched analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13(11):1244-52.

12. Katz AM. Potential deleterious effects of inotropic agents

in the therapy of chronic heart failure. Circulation 1986;73(3

Pt 2):III184-90.

13. O’Connor CM, Gattis WA, Uretsky BF et al. Continuous

intravenous dobutamine is associated with an increased risk

of death in patients with advanced heart failure: insights

from the Flolan International Randomized Survival Trial

(FIRST). Am Heart J 1999;138(1 Pt 1):78-86.

14. Kellum JA, M Decker J. Use of dopamine in acute renal

failure: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2001;29(8):1526-31.

15. Lowes BD, Tsvetkova T, Eichhorn EJ, Gilbert EM, Bristow

MR. Milrinone versus dobutamine in heart failure subjects

treated chronically with carvedilol. Int J Cardiol 2001;81(2-

3):141-9.

16. Böhm M, Deutsch HJ, Hartmann D, Rosée KL, Stäblein

A. Improvement of postreceptor events by metoprolol

treatment in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll

Cardiol 1997;30(4):992-6.

17. Mebazaa A, Gheorghiade M, Piña IL et al. Practical

recommendations for prehospital and early in-hospital

management of patients presenting with acute heart failure

syndromes. Crit Care Med 2008;36(1 Suppl.):S129-39.

18. Cleland JG, McGowan J. Levosimendan: a new era for

inodilator therapy for heart failure? Curr Opin Cardiol

2002;17(3):257-65.

19. Slawsky MT, Colucci WS, Gottlieb SS et al.; on behalf of

the Study Investigators. Acute hemodynamic and clinical

effects of levosimendan in patients with severe heart failure.

Circulation 2000;102(18):2222-7.

Références bibliographiques

1

/

5

100%