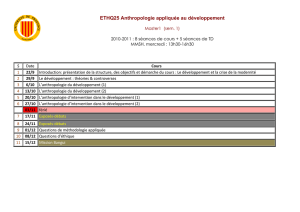

Intervention Ethnobotanique et Ethnosciences : quelques éléments

Intervention Ethnobotanique et Ethnosciences : quelques éléments de théories et de

pratiques (accent sur le courant américaniste)

Julien Blanc

Version 2016

Introduction

Séance à objectifs multiples:

1. Vous donner des bases pour effectuer des recherches en relation avec l’étude des

classifications populaires des plantes et des animaux (« méthode »)

2. Contribuer à situer les ethnosciences au sein de l’anthropologie (compléter les

précédentes présentations)

3. L’un dans l’autre, cela permettra également de souligner combien le problème des

catégories dans les systèmes de pensée autres que le nôtre est capital pour

l’anthropologie et comment la façon de l’aborder a évolué depuis un siècle.

4. La séance constituera également l’occasion d’évoquer différentes formes, passées et

contemporaine de mobilisation de l’ethnobotanique : ce pour quoi elle a été fondée et

est utilisé (permettra à la fois de compléter les précédentes présentations et d’ouvrir sur

les suivantes).

Donc, je vais glisser d’un registre à l’autre (éléments d’histoire, de méthode, de théorie

tout au long de la présentation).

Cadrage résolument Anthropologique / Ethnologique.

COURANT DES ETHNOSCIENCES :

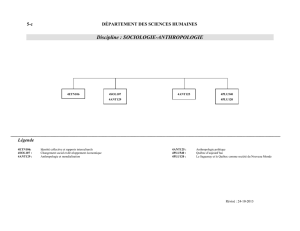

Marqué par un certains nombre d’individus : Harold Conklin (1954), William Stutervant,

Stephen Tyler, Brent Berlin, Ralph Bulmer : Antrhopologues – Université de Yale.

Conklin, H. C. (1954). The Relation of Hanunóo Culture to the Plant World. Thèse. Yale University.

Bulmer, R. (1967). Why is the Cassowary Not a Bird ? A Problem of Zoological Taxonomy Among the

Karam of the New Guinea Highlands. Man, 2(1), 5–25.

Berlin, B., Breedlove, D., & Raven, P. (1973). General principles of classification and nomenclature in

folk biology. American Anthropologist, 75(1), 214–242.

Sturtevant, W. (1964). Studies in ethnoscience. American Anthropologist, 66(3), 99–131.

Berlin, B., & Kay, P. (1969). Basic Color Terms: Their Universality and Evolution. Berkeley : University

of California Press.

Conklin, H. C. (1955). Hanunóo color categories. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology.

Site du Departement d’anthropologie d’Alabama : ramené à l’anthropologie cognitive.

Cognitive anthropology : Ethnosemantics, Ethnoscience, Ethnolinguistics, and New Ethnography.

« Cognitive anthropology addresses the ways in which people conceive of and think about events

and objects in the world. It provides a link between human thought processes and the physical

and ideational aspects of culture (D’Andrade 1995: 1). This subfield of anthropology is rooted in

Boasian cultural relativism, influenced by anthropological linguistics, and closely aligned with

psychological investigations of cognitive processes. It arose as a separate area of study in the

1950s, as ethnographers sought to discover “the native’s point of view,” adopting an emic

approach to anthropology (Erickson and Murphy 2003: 115). The new field was alternatively

referred to as Ethnosemantics, Ethnoscience, Ethnolinguistics, and New Ethnography. »

Cognitive anthropology, leading figures

Ward Goodenough (b. 1919) is one of cognitive anthropology’s early leading scholars, inaugurating

the subdiscipline in 1956 with the publication of “Componential Analysis and the Study of

Meaning” in a volume of Language. He helped to establish a methodology for studying cultural

systems. His fundamental contribution was in the framing of componential analysis, Borrowing

its methods from linguistic anthropology, involved the construction of a matrix that contrasted

the binary attributes of a domain in terms of pluses (presence) and minuses (absence).

"Componential Analysis and the Study of Meaning" (1956) and "Componential Analysis of

Konkama Lapp Kinship Terminologies" (1964).

Floyd Lounsbury (1914-1998) was another influential figure in the rise of the subdiscipline. His

analysis of Pawnee kinship terms, “A Semantic Analysis of the Pawnee Kinship Usage” was

published in 1956.

Charles Frake (b. 1930) He also emphasized that the ethnographer "should strive to define objects

according to the conceptual system of the people he is studying" (1969:28), or in other words

elicit a domain. He argued that studies of how people think have historically sought evidence of

"primitive thinking" instead actually investigating the processes of cognition. He contends that

future studies should match the methodological rigor of kinship and should aim for developing

a native understanding of the world. He promotes a "bottom up" approach where the

ethnographer firsts attains the domain items (on the segregates) of different categories (or

contrast sets). The goal, according to Frake, is to create a taxonomy so differences between

contrasting sets are demonstrated in addition to how the attributes of contrasting sets relate to

each other.

Harold Conklin (b. 1926)

A. Kimball Romney’s (b. 1925) many contributions to cognitive anthropology include the

development of consensus theory. Unlike most methods that are concerned with the

reliability of data, the consensus method statistically measures the reliability of individual

informants in relation to each other and in reference to the group as a whole. It

demonstrates how accurately a particular person’s knowledge of a domain corresponds with

the domain knowledge established by several individuals. In other words, the competency of

individuals as informants is measured. For specifics about how cultural consensus works, see

the "Methodology" section of this web page. In a recent article in Current Anthropology,

"Cultural Consensus as a Statistical Model" (1999), there is an intriguing exchange between

Aunger who opposes consensus theory and Romney who rebuts Aunger’s criticisms. Romney

maintains that cultural consensus is a statistical model that does not pre-suppose an

ideological alignment, as Aunger asserts, but rather it demonstrates any existing

relationships between variables.

Autre histoire: lignée de l’ethnobiologie:

Reference : Heugene Hunn (2007):

Hunn, E. (2007). Ethnobiology in four phases. Journal of Ethnobiology, 27(1), 1–10.

Harshberger, Castetter et bien d’autres – ethnobotanique, ethnozoologie, etc. Naturalistes &

ethnologues.

A partier des années 20, les ethnologues vont se saisir de l’ethnobotanique et commencer à la

transformer pour de plus en plus s’intéresser à aux représentations du monde sous-jacents à

l’usage des plantes, approche plus emic.

Si on suit cette ligne les travaux de Conklin sont considérés comme un virage:

« Notre intérêt premier ne concerne pas les données botaniques taxinomiques, mais plutôt le

savoir populaire botanique des Hanunóo et son organisation. Les considérations botaniques

scientifiques sont secondaires et sont incluses seulement pour éclairer la comparaison entre

deux domaines sémantiques » (Conklin, 1954, p. 11).

Il propose de partir des catégories sémantiques indigènes pour étudier la connaissance qu’une

société a de son environnement. Il dépasse ainsi l’approche essentiellement étic — réalité telle

qu’elle est perçue de l’extérieur — qui dominait avec des perspectives utilitaristes pour prôner

une approche émic — concepts propres à la culture étudiée – des connaissances et des

classifications pour comprendre et conceptualiser comment le milieu naturel fait sens pour une

société donnée (Clément, 1998b; Friedberg, 1991b).

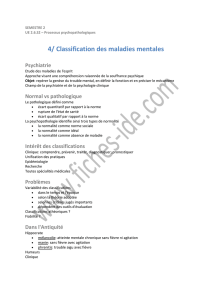

I. Retour en arrière : le texte considéré comme fondateur.

Dans le domaine des classifications en anthropologie, l’article fondateur est celui de

Durkheim et Mauss. Paru dans l’Année Sociologique, 1903 : « de quelques formes primitives

de classification, contribution à l’étude des représentations collectives »

CONTENU DU TEXTE :

D et M analysent « les systèmes de classification » de différents peuples (tribus) : ils

commencent par différentes tribus australiennes" puis continuent par des Indiens

d'Amérique du nord (Zunis, Osages, Omahas, etc).

Ils présentent des systèmes de classifications dans lesquelles entrent quelques plantes,

quelques astres et éléments de l'univers, mais principalement des animaux qu’ils relient

avec l'organisation sociale de ces populations.

En fait, ils montrent comment divers éléments de l'environnement se trouvent répartis

entre des catégories qui servent d'abord à différencier les hommes: fratries, clans,

classes matrimoniales

Ce texte est fondateur pourquoi ? :

1. Affirmation de l’existence chez les tous les individus d’un procédé qui consiste à classer

les êtres, les évènements, les faits du monde, et à déterminer leur rapports (universalité)

et plus particulièrement qu’il existe chez les primitifs une pensée logique similaire sous

certains aspects à la pensée scientifique :

a. qui marche sur la base d’inclusion, d’exclusion, de hiérarchisation

b. les catégorisations ne sont pas uniquement de nature utilitaire, loin s’en faut,

mais plus largement spéculative » (réflexion intellectuelle portant sur des

objets abstrait).

CITATION

« Les classifications primitives ne constituent donc pas des singularités exceptionnelles

sans analogies avec celles qui sont en usage chez les peuples plus cultivés ; elles semblent

au contraire se rattacher sans solution de continuité aux premières classifications

scientifiques. C’est qu’en effet, si profondément qu’elles diffèrent de ces dernières sous

certains rapports, elles ne laissent cependant pas d’en avoir tous les caractères essentiels.

Tout d’abord, elles sont, tout comme les classifications des savants des systèmes de

notion hiérarchiques. (…) De plus, ces systèmes, tout comme ceux de la science, ont un

but spéculatif. Ils ont pour objet, non de faciliter l’action, mais de faire comprendre, de

rendre intelligible les relations qui existent entre les êtres ». (Durkheim et Mauss, 1903 :

66)

On retrouvera cette démarche notamment dans la « pensée sauvage » (1962) où Lévi-

Strauss cherche à décrire les mécanismes de la pensée en tant qu'attribut universel de

l'esprit humain : tentative de démonstration que peu de chose démarque la pensée du

« sauvage » de celle du « civilisé » ; Les deux premiers chapitres intitulés « La Science du

Concret » et « La Logique des Classifications Totémiques » cherchent à convaincre le lecteur

de cette universalité de la pensée, et surtout de l'uniformité des capacités intellectuelles et

conceptuelles des hommes quel que soit leur degré de civilisation.

On va voir en fait que c’est un programme fort des ethnosciences, que l’on retrouve

d’ailleurs plus tard dans la valorisation des « savoirs locaux ».

En réaction notamment aux théories évolutionnistes (Morgan, Spencer, Frazer) marquée par

le préjugé d'une supériorité de la civilisation occidentale sur celles des « sauvages ».

APPARTE

En fait il est fondateur pour autre chose, et s’inscrit dans une autre controverse de l’époque, mais je ne la

développerai pas (déterministe social ou naturel des classification)

En effet, 2ème affirmation majeure : il existe une relation non accidentelle entre un système logique de

classification des non-humains (plantes, animaux notamment) et un système social: dans les sociétés étudiées

les systèmes de classification des non-humains (plantes, animaux notamment) expriment les systèmes de

relations sociales où ils sont élaborés (organisation juridique et religieuse, parenté). ET plus encore : C'est sur

l'organisation sociale la plus proche et la plus fondamentale que ces classifications ont été modelées.... Les

premières catégories logiques ont été des catégories sociales ».

• Pour bien comprendre D et M il faut les replacer dans le contexte des débats théoriques quand ce texte a

été écrit : démontrer indépendance des faits sociaux vis à vis d'un soi-disant déterminisme du milieu

naturel. Ainsi affirment-ils: "Bien loin que, comme semble l'admettre M.Frazer ce soient les relations

logiques des choses qui aient servi de base aux relations sociales des hommes, en réalité ce sont celles-ci

qui ont servi de prototype à celles-là (p.224).

• Evidemment aujourd’hui, personne ne considère plus que ce sont les modes d’organisation sociales qui

aussi unilatéralement déterminent les catégorisations et classifications des éléments (êtres) de nous

considérons comme éléments de nature. Ils y participent mais personnes ne conçoit plus les choses dans

des rapports aussi brutalement déterministes, dans un sens ou dans un autre.

2. Les auteurs ouvrent la voie à l’importance qu’il faut accorder à l’étude des

catégorisations autochtones : soulignent l’importance de la description et

l’interprétation de ces mises en ordre. (idée qui sera notamment reprise par les

ethnosciences, à la base de leur programme).

3. Début d’interrogation sur la raison pour laquelle ces processus de catégorisation et

classifications semblent universels, partagés, mais celui-ci reste pour eux assez

mystérieux (A cette époque, on ne connait vraiment rien de ces phénomènes : La

Psychologie, alors naissante en tant que discipline scientifique, commence à s’intéresser

à ces questions à cette époque également ; Psychologie cognitive : 1930 environ) :

CITATION

« C’est donc que les mêmes sentiments qui sont à la base de l’organisation domestique,

sociale, etc. , ont aussi présidé à cette répartition logique des choses (…). Ce sont donc des

était de l’âme collective qui ont donné naissance à ces groupements » (…) Nous ignorons

encore quelles sont les forces qui ont induit les hommes à répartir les choses selon la

méthode qu’ils ont adoptée »

Par contre, ce que Durkheim et Mauss entendent par classification, c'est un système de

classes mutuellement exclusives et hiérarchisées correspondant au modèle des taxinomies

scientifiques, ce qui, comme on va le voir pose problème (ici aussi, on peut y voir une

volonté de démontrer l’unité de l’être humain).

TRANSITION

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

1

/

14

100%