Lire l`article complet

MISE AU POINT

24 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 435 - mai 2010

Quand faut-il rechercher

une ischémie myocardique avant

une chirurgie extra-cardiaque ?

When should myocardial ischemia be looked for prior to

non-cardiac surgery?

V. Piriou*

* Service d’anesthésie-réanimation,

centre hospitalier de Lyon-Sud, Pierre-

Bénite.

L

es principaux examens à réaliser en préopératoire

pour rechercher une ischémie myocardique sont

des examens de stress, tels que la scintigraphie

myocardique ou l’échocardiographie à la dobutamine.

Ces examens peuvent être prescrits lors de la période

préopératoire dans le cadre du dépistage ou de la

quantification d’une ischémie myocardique.

La réalisation de tels examens complémentaires

doit tenir compte du contexte économique et n’est

justifiée que si le résultat de ces examens peut

permettre une meilleure quantification du risque

ou une modification de la stratégie périopératoire.

La prescription d’un examen de stress ne devra être

réalisée qu’avec l’arrière-pensée de l’optimisation de

la stratégie de prise en charge. Il faudra d’emblée se

projeter sur la conduite à tenir en cas d’examen de

stress positif : optimisation du traitement médical,

voire revascularisation préopératoire.

Lorsqu’une intervention chirurgicale doit être réalisée

en urgence, ou en semi-urgence, avec un délai qui

ne peut pas être allongé (cas de la chirurgie carci-

nologique, par exemple), le retard entraîné par la

réalisation d’éventuels examens complémentaires

doit être mis en balance avec le bénéfice lié à la

réalisation de ces examens. Dans ce cas, il faut se

poser la question de l’optimisation du traitement

médical et de la réalisation des examens de stress

en postopératoire.

Pourquoi faut-il réaliser

des examens de stress

pour détecter l’ischémie

des patients ?

Les complications cardiovasculaires sont d’autant

plus fréquentes que les patients sont opérés d’une

chirurgie à risque. La chirurgie la plus à risque est

représentée par la chirurgie vasculaire, pour deux

causes principales : la chirurgie vasculaire aortique

entraîne des contraintes hémodynamiques et

des variations pressionnelles importantes, et elle

concerne des patients présentant des atteintes

athéromateuses diffuses, qui ont donc un risque

coronarien important. D’autre part, on sait qu’il

existe une relation directe entre la mortalité à long

terme et l’élévation postopératoire de la troponine,

la mortalité étant directement corrélée à l’intensité

du pic de troponine postopératoire (1). La détection

d’une coronaropathie en préopératoire a pour but de

mieux stratifier le risque des patients, et de diminuer

ce risque en apportant soit un traitement médical,

soit un traitement de la lésion coronaire.

Une étude récente a montré qu’une échocardio-

graphie à la dobutamine positive, révélant de

nouvelles anomalies segmentaires en préopératoire,

est assez bien corrélée à l’apparition de complica-

tions cardiaques postopératoires. Cependant, la

localisation des anomalies révélées lors de l’écho-

cardiographie de stress était très mal corrélée à la

localisation des anomalies constatées en peropé-

ratoire en échocardiographie transœsophagienne

(ETO). Ces examens de stress sont donc incapables

de prédire la localisation des ruptures de plaques

vulnérables en périopératoire, d’autant plus que

ce ne sont pas les plaques les plus sténosantes qui

sont les plus instables, et donc à risque de compli-

cation (2, 3). Cela explique les résultats négatifs des

essais randomisés ayant comparé la revascularisation

préopératoire d’une lésion coronaire sténosante à

un traitement médical optimisé sous couvert de

statine et de bêtabloquant. En effet, l’étude CARP,

qui a inclus 510 patients de chirurgie vasculaire,

en excluant les patients à très haut risque, n’a pas

La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 435 - mai 2010 | 25

Points forts

»

Les examens pour rechercher une ischémie myocardique avant une chirurgie extra-cardiaque sont la

scintigraphie et l’échocardiographie à la dobutamine.

»Leur réalisation doit permettre de modifier la prise en charge et le pronostic des patients.

»Ils doivent être réservés aux patients les plus à risque et ayant une capacité fonctionnelle faible.

Mots-clés

Risque coronarien

Chirurgie

extra-cardiaque

Scintigraphie

myocardique

Échocardiographie

à la dobutamine

Highlights

»

Dobutamine stress echocar-

diography and nuclear perfu-

sion imaging are the main

preoperative tests to diagnose

a myocardial ischemia before

non cardiac surgery.

»

Testing should be performed

only if it changes periopera-

tive management and patient

prognosis.

»

Preoperative stress testing is

indicated in high risk patients

with a low functional capacity.

Keywords

Coronary risk

Non cardiac surgery

Scintigraphy

Dobutamine stress

echography

montré de bénéfice d’une revascularisation préopé-

ratoire, que ce soit par pontage coronarien ou par

endoprothèse (4). Les indications de revasculari-

sation préopératoire, faisant suite à un test positif,

doivent donc être limitées aux patients les plus à

risque, tels que ceux présentant une sténose du tronc

coronaire gauche (5), les patients tritronculaires à

fraction d’éjection basse, ou les patients présentant

un angor instable (6). Cependant, dans tous les cas,

si une indication de revascularisation est proposée,

celle-ci doit être discutée d’un commun accord entre

les équipes anesthésique, chirurgicale et cardiolo-

gique, et le choix de la technique de revascularisation

préopératoire doit, dans tous les cas, tenir compte

du risque postopératoire lié à la mise en place d’une

endoprothèse coronaire et de la gestion délicate des

antiagrégants plaquettaires dans ces conditions.

À qui faut-il prescrire

des examens de stress ?

Les examens de stress doivent être prescrits pour

poser le diagnostic d’athérome coronarien symp-

tomatique, ou pour évaluer le degré de sévérité du

niveau de stress par lequel cet athérome coronarien

s’exprime, afin d’affiner la stratégie thérapeutique.

Si le patient a été exploré depuis moins d’un an et

qu’il n’a pas présenté de déstabilisation de son état

coronarien, il est inutile de le tester à nouveau. En

revanche, il faudra communiquer à l’équipe anesthé-

sique et chirurgicale le résultat des examens réalisés.

Les examens de stress préopératoires peuvent être

recommandés en l’absence d’exploration récente, si :

– le patient est opéré d’une chirurgie à risque, et

s’il présente une probabilité de coronaropathie

suspectée par des facteurs de risque importants ;

– le patient rapporte une modification récente de

son statut fonctionnel ;

– le patient a présenté un syndrome coronarien aigu.

Les patients à bas risque ne tireront aucun bénéfice

de la réalisation d’un examen de stress préopératoire.

Ce sont les patients qui présentent au moins deux

facteurs de risque cliniques qui bénéficieront de la

réalisation d’un examen de stress préopératoire dans

le cadre d’une chirurgie à risque intermédiaire ou

d’une chirurgie à haut risque.

L’étude DECREASE II a montré que, sous réserve

que les patients soient bien traités médicalement,

il est inutile de proposer des examens de stress

préopératoires à des patients à risque intermé-

diaire (présentant un ou deux facteurs de risque)

[7]. Dans ce contexte, la réalisation des examens

de stress n’améliore pas la survie postopératoire,

mais a pour seul effet de retarder de 3 semaines

la chirurgie.

Facteurs à prendre

en considération

Pour déterminer le risque du patient et les indica-

tions potentielles des examens de stress préopéra-

toires, il est nécessaire d’évaluer plusieurs facteurs

lors de la consultation d’anesthésie, ou lors de la

visite préopératoire chez le cardiologue.

Analyse des facteurs

de risque cliniques

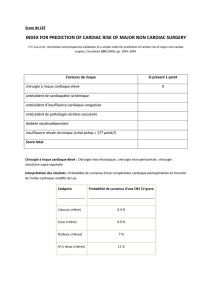

Les facteurs de risque de complications cardiaques

postopératoires retenus sont ceux décrits dans le

score de Lee (8). Ces facteurs de risque cliniques

sont les suivants : antécédents de cardiopathie isché-

mique non revascularisée, antécédents d’insuffisance

cardiaque, antécédents d’accident vasculaire cérébral

ou d’accident ischémique transitoire, antécédents

de diabète insulino-requérant, insuffisance rénale.

Plus les patients cumulent ces facteurs de risque,

plus ils ont un risque de complication élevé. Ce score

a été validé pour tout type de chirurgie vasculaire,

mais aussi thoracique, digestive, orthopédique, etc.

Ce score de risque prédit la survie à long terme en

postopératoire (9). À ces 5 déterminants cliniques

indépendants, on peut ajouter l’âge, qui améliore

la valeur pronostique du modèle (10).

Chez certains patients à haut risque, la stratification

peut être affinée par le dosage de biomarqueurs

préopératoires, tels que le BNP (brain natriuretic

peptide) [11], bien que l’utilisation de ces biomar-

queurs demande encore une validation. Dans tous

les cas, les biomarqueurs ne peuvent pas être utilisés

en routine pour prédire le risque.

Quand faut-il rechercher une ischémie myocardique

avant une chirurgie extra-cardiaque ?

MISE AU POINT

26 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 435 - mai 2010

La capacité fonctionnelle des patients

doit être évaluée

Les patients qui ont une bonne capacité fonction-

nelle, c’est-à-dire supérieure à 4 équivalents méta-

boliques, n’auront pas besoin d’examens de stress,

car le risque opératoire est faible. En effet, lorsque

la capacité fonctionnelle des patients est élevée,

le pronostic est excellent, même en présence de

facteurs de risque importants (12). Une capacité

fonctionnelle de 4 équivalents métaboliques corres-

pond à l’aptitude à monter deux escaliers, ou à courir

sur une courte distance.

Quels examens réaliser ?

Électrocardiogramme de repos

L’électrocardiogramme de repos devra être réalisé

chez des patients à risque afin de servir d’examen de

référence permettant de diagnostiquer une compli-

cation postopératoire, révélée par des anomalies

électriques nouvelles, et de déterminer des anoma-

lies électriques préexistantes traduisant un risque

de coronaropathie ou un événement récent (sus-

décalage du segment ST, sous-décalage, inversion

des ondes T) ou ancien (ondes Q dans un territoire).

Chez les patients à bas risque, la réalisation d’un

électrocardiogramme préopératoire est inutile (13).

Chez les patients coronariens stables, si un électro-

cardiogramme a été réalisé dans l’année écoulée, il

est inutile d’en refaire un. En revanche, il convient

de récupérer cet examen et de le transmettre aux

équipes anesthésique et chirurgicale. Dans le cadre

d’une chirurgie à faible risque, la réalisation d’un

électrocardiogramme de repos est inutile.

Examens de stress :

scintigraphie myocardique

et échocardiographie à la dobutamine

Les examens de stress préopératoires ont pour

caractéristique de présenter une valeur prédictive

négative élevée comprise entre 90 et 95 %, et une

valeur prédictive positive faible, entre 5 et 10 %

(14). Les quelques méta-analyses publiées compa-

rant scintigraphie et échocardiographie de stress

à la dobutamine sont plutôt en faveur de l’écho-

cardiographie de stress pour prédire les complica-

tions postopératoires (15), d’autant plus que cette

dernière entraîne moins d’irradiation (16). En fait,

ce sont souvent les possibilités locales qui dictent

le choix entre ces deux examens. L’échographie de

repos ne présente pas d’intérêt pour dépister le

risque coronarien préopératoire ; par contre, une

fraction d’éjection préopératoire basse représente

un facteur de risque de complication cardiaque

postopératoire (17).

Lors d’un examen de stress, plus la zone ischémique

est importante, plus le risque postopératoire est

important. Pour la scintigraphie, le risque est impor-

tant en cas de défect réversible représentant plus

de 15 à 20 % de la masse ventriculaire gauche (18) ;

pour l’échocardiographie de stress, le pronostic est

défavorable lorsque l’ischémie occupe plus de 4 terri-

toires sur 17 (19).

L’angio-scanner, l’IRM, ou la tomographie par

émission de positons n’ont pas été évalués pour

la détection du risque coronaire dans le contexte

périopératoire. Du fait de l’absence d’évaluation

de ces examens, leur réalisation en préopératoire

ne peut pas être recommandée.

En pratique

Plusieurs points méritent

d’être considérés successivement

L’existence d’une situation cardiaque évolutive

doit faire repousser toute chirurgie non urgente ou

non vitale, car elle témoigne de conditions cliniques

instables représentant un facteur de risque majeur

de déstabilisation de l’état cardiaque : présence d’un

syndrome coronarien aigu, d’un angor sévère de

classe III ou IV (classification canadienne), existence

d’une insuffisance cardiaque décompensée ou d’une

valvulopathie sévère, notamment une valvulopathie

sténosante.

La classification du risque lié à la chirurgie : les

chirurgies artérielles vasculaires sont toutes consi-

dérées comme étant à haut risque. Les chirurgies à

faible risque sont les actes d’endoscopie, les chirur-

gies ophtalmologiques, les chirurgies superficielles

(sein), les chirurgies gynécologiques, orthopédiques

et urologiques mineures. Les chirurgies à risque

intermédiaire sont toutes les autres chirurgies :

abdominales, carotidiennes, chirurgies majeures

de la tête et du cou, chirurgie orthopédique majeure,

chirurgie de transplantation, chirurgie urologique

majeure.

Les patients opérés d’une chirurgie mineure n’ont

pas besoin d’examen de stress complémentaire en

raison de la faible incidence des complications.

MISE AU POINT

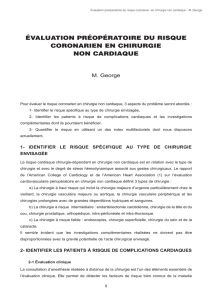

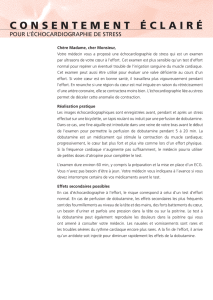

Figure. Algorithme de synthèse (proposition du groupe de travail chargé des recomman-

dations “Prise en charge du coronarien qui doit être opéré en chirurgie non cardiaque”

(SFAR-SFC).

Chirurgie urgente

Patient stable

Capacité fonctionnelle

≥ 4 MET < 4 MET

Test d’ischémie

Chirurgie

Optimisation du traitement médical préopératoire

Patient stablePatient instable

Chirurgie non urgente

Chirurgie à risque

intermédiaire

ou élevé

Chirurgie

à faible risque

Facteur de risque

clinique < 2

Facteur de risque

clinique > 3

– Retarder la chirurgie

et discussion collégiale

– Traitements spécifiques

– Discuter l’opportunité

d’une éventuelle revascularisation

– Surveillance per- et post-

opératoire rapprochée

– +

La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 435 - mai 2010 | 27

L’évaluation de la capacité fonctionnelle : un

patient capable de réaliser un effort d’au moins

4 équivalents métaboliques sans symptôme pourra

supporter sans problème le stress opératoire et se

passer ainsi, dans la majorité des cas, d’examens

complémentaires cardiovasculaires.

Le risque lié au patient est évalué à partir des

5 facteurs de risque clinique du score de Lee. Un

patient présentant un score de Lee faible ou intermé-

diaire (≤ 2 facteurs de risque) n’a pas besoin d’exa-

mens complémentaires, sous réserve qu’il bénéficie

d’un traitement médical adapté (20). Plus le nombre

de facteurs de risque est important, plus la préva-

lence de la maladie coronarienne est élevée, plus le

risque de complication périopératoire est augmenté

et plus l’indication d’un examen de stress préopé-

ratoire est évidente (21).

En cas d’examen de stress positif, la place de l’in-

dication de revascularisation préopératoire doit

être systématiquement mise en balance avec un

traitement médical optimisé par un traitement par

bêtabloquant, statines et, éventuellement, antia-

grégant plaquettaire par aspirine. Dans tous les cas,

les patients à risque bénéficieront d’une prise en

charge périopératoire particulière avec un respect de

la balance en oxygène (prise en charge des hypoten-

sions, des hypertensions artérielles périopératoires,

de la tachycardie, de la normothermie peropératoire

avec prévention de l’hypothermie, transfusion en cas

d’anémie caractérisée par une hémoglobine inférieure

à 10 g/dl, prévention de l’hypoxémie). Ces patients

bénéficieront du monitorage per- et postopératoire

en SSPI du segment ST, d’électrocardiogrammes

postopératoires réguliers et du monitorage biolo-

gique par le dosage postopératoire de la troponine Ic.

Algorithme de prise en charge (figure)

En cas de chirurgie urgente, le patient sera évalué

a posteriori.

Si la chirurgie est élective, c’est-à-dire non urgente, il

convient d’écarter une pathologie cardiaque instable,

qui nécessite un traitement spécifique selon les

recommandations en vigueur avant l’intervention

chirurgicale.

En l’absence de pathologie cardiaque instable, le

risque chirurgical sera évalué :

➤

en cas de risque chirurgical faible, le patient

pourra être opéré sans qu’un test d’effort soit

nécessaire ;

➤

en cas de risque chirurgical intermédiaire à élevé,

la capacité fonctionnelle du patient sera évaluée :

– si celle-ci est correcte, c’est-à-dire d’au moins

4 équivalents métaboliques, la chirurgie pourra être

effectuée sans réaliser de test à la recherche d’une

ischémie. Chez les patients cumulant les facteurs

de risque cliniques du score de Lee, le traitement

médical sera continué, voire optimisé (il ne faut

jamais arrêter un traitement par bêtabloquant ou

par statines chez un patient prenant ce traitement

de façon chronique). L’introduction d’un traitement

médical peut, dans ce cas, être discutée si le patient

ne bénéficiait pas d’un tel traitement ;

– lorsque la capacité à l’effort est diminuée, ou si

elle n’est pas évaluable, le nombre de facteurs de

risque cliniques du score de Lee intervient, celui-ci

étant modulé par le type de chirurgie :

• lorsque le patient n’a pas de facteur clinique ou a un

seul facteur de risque, la chirurgie peut être réalisée ;

Quand faut-il rechercher une ischémie myocardique

avant une chirurgie extra-cardiaque ?

MISE AU POINT

28 | La Lettre du Cardiologue • n° 435 - mai 2010

• lorsque le patient présente plus de deux facteurs

de risque, l’indication d’un examen de stress doit

être discutée de façon consensuelle entre les

équipes d’anesthésie et de chirurgie et les équipes

de cardiologie. La décision de réaliser un examen de

stress devra être envisagée par rapport à la réalisa-

tion de la chirurgie sous bêtabloquants et statines

(figure, p. 27).

La réalisation d’un test d’ischémie est donc limitée

aux patients qui présentent une capacité fonc-

tionnelle diminuée et plusieurs facteurs de risque

cliniques, ainsi que dans le cas d’une chirurgie à

risque intermédiaire ou d’une chirurgie vasculaire.

Conclusion

Les principaux examens de stress à proposer dans le

cadre de l’évaluation préopératoire du risque coro-

narien sont la scintigraphie et l’échocardiographie de

stress. Au fil des ans, les recommandations se sont

affinées et ont restreint ces examens aux patients les

plus à risque, dans le cadre d’une chirurgie à risque,

chez lesquels les examens vont modifier la stratégie

thérapeutique. En effet, le risque a progressivement

diminué pour se concentrer sur les patients les plus

à risque, probablement par l’amélioration de la prise

en charge périopératoire et par les progrès liés au

traitement médical des patients à risque coronarien.

Une littérature de plus en plus abondante et convain-

cante souligne l’intérêt de l’optimisation du traite-

ment médicamenteux des patients à risque (22).

La perspective d’une chirurgie doit peu influencer

la prise en charge du patient à risque coronarien,

mais elle est l’occasion d’une optimisation de son

traitement. Une grande majorité de patients coro-

nariens ou de patients à risque peut être opérée sans

nécessité de bilan complémentaire, sous réserve d’un

traitement médical adapté. Les bilans complémen-

taires sont réservés aux patients à risque, à faible

capacité fonctionnelle, candidats à une chirurgie à

haut risque ou éventuellement à risque intermé-

diaire. Devant l’existence de facteurs de mauvais

pronostic révélés par ces explorations, une réflexion

consensuelle pluridisciplinaire, intégrant les équipes

de chirurgie, d’anesthésie et de cardiologie, doit

mettre en balance une stratégie invasive face à une

optimisation médicale. ■

1. Landesberg G, Shatz V, Akopnik I et al. Association of

cardiac troponin, CK-MB, and postoperative myocardial

ischemia with long-term survival after major vascular

surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1547-54.

2. Little WC, Constantinescu M, Applegate RJ et al. Can

coronary angiography predict the site of a subsequent

myocardial infarction in patients with mild-to-moderate

coronary artery disease? Circulation 1988;78:1157-66.

3. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK et al. Optimal medical

therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease.

N Engl J Med 2007;356:1503-16.

4. McFalls EO, Ward HB, Moritz TE et al. Coronary-artery

revascularization before elective major vascular surgery.

N Engl J Med 2004;351:2795-804.

5. Garcia S, Moritz TE, Ward HB et al. Usefulness of revas-

cularization of patients with multivessel coronary artery

disease before elective vascular surgery for abdominal

aortic and peripheral occlusive disease. Am J Cardiol 2008;

102:809-13.

6. Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA et al. ACC/AHA 2007

guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and

care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College

of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on

Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002

Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for

Noncardiac Surgery): developed in collaboration with the

American Society of Echocardiography, American Society

of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of

Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovas-

cular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular

Medicine and Biology, and Society for Vascular Surgery.

Circulation 2007;116:e418-99.

7. Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Schouten O et al. Should major vascular

surgery be delayed because of preoperative cardiac testing in

intermediate-risk patients receiving beta-blocker therapy with

tight heart rate control? J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:964-9.

8. Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM et al. Derivation

and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction

of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation

1999;100:1043-9.

9. Hoeks SE, op Reimer WJ, van Gestel YR et al. Preoperative

cardiac risk index predicts long-term mortality and health

status. Am J Med 2009;122:559-65.

10. Boersma E, Kertai MD, Schouten O et al. Perioperative

cardiovascular mortality in noncardiac surgery: validation

of the Lee cardiac risk index. Am J Med 2005;118:1134-41.

11. Cuthbertson BH, Amiri AR, Croal BL et al. Utility of B-type

natriuretic peptide in predicting perioperative cardiac events

in patients undergoing major non-cardiac surgery. Br J

Anaesth 2007;99:170-6.

12. Morris CK, Ueshima K, Kawaguchi T, Hideg A, Froeli-

cher VF.The prognostic value of exercise capacity: a review

of the literature. Am Heart J 1991;122:1423-31.

13. Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Bax JJ et al. Prognostic value of

routine preoperative electrocardiography in patients under-

going noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2006;97:1103-6.

14. Kertai MD, Boersma E, Sicari R et al. Which stress test

is superior for perioperative cardiac risk stratification in

patients undergoing major vascular surgery? Eur J Vasc

Endovasc Surg 2002;24:222-9.

15. Kertai MD, Boersma E, Bax JJ et al. A meta-analysis

comparing the prognostic accuracy of six diagnostic tests

for predicting perioperative cardiac risk in patients under-

going major vascular surgery. Heart 2003;89:1327-34.

16. Sicari R, Nihoyannopoulos P, Evangelista A et al. Stress

echocardiography expert consensus statement: European

Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch

of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr 2008;9:415-37.

17. Rohde LE, Polanczyk CA, Goldman L, Cook EF, Lee RT,

Lee TH. Usefulness of transthoracic echocardiography as

a tool for risk stratification of patients undergoing major

noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2001;87:505-9.

18. Etchells E, Meade M, Tomlinson G, Cook D. Semiquanti-

tative dipyridamole myocardial stress perfusion imaging for

cardiac risk assessment before noncardiac vascular surgery:

a meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg 2002;36:534-40.

19. Boersma E, Poldermans D, Bax JJ et al. Predictors of

cardiac events after major vascular surgery: Role of clinical

characteristics, dobutamine echocardiography, and beta-

blocker therapy. JAMA 2001;285:1865-73.

20. Poldermans D, Hoeks SE, Feringa HH. Pre-operative

risk assessment and risk reduction before surgery. J Am Coll

Cardiol 2008;51:1913-24.

21. Wijeysundera DN, Beattie WS, Austin PC, Hux JE,

Laupacis A. Non-invasive cardiac stress testing before elec-

tive major non-cardiac surgery: population based cohort

study. BMJ 2010;340:b5526.

22. Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Boersma E et al.; Task Force for

Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative

Cardiac Management in Non-cardiac Surgery of the Euro-

pean Society of Cardiology (ESC) and endorsed by the

European Society of Anaesthesiology (ESA). Guidelines

for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative

cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J

2009;39:2769-812.

Références bibliographiques

1

/

5

100%