James, Albert, Michel, Jean-Marc et les autres... ou L

James, Albert, Michel,

Jean-Marc et les autres...

ou

L’électromagnétisme galiléen revisité

Germain Rousseaux

INLN – UMR 6618 CNRS,

1361, route des Lucioles,

06560 Valbonne

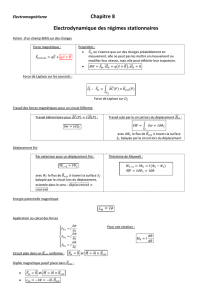

La Formulation de Heaviside-Hertz

0. =

∂

∂

+∇t

j

ρ

00

1

εµ

=

L

c

AB ×∇=

V∇∂=-A-E t

0. =∇B

Equation de Thomson

E-B ×∇=∂t

Equation de Faraday

0

.

ε

ρ

=∇E

Equation de Gauss

EjB 0t

L

c∂+=×∇ 2

1

µ

Equation d'Ampère

La Formulation de Riemann-Lorenz

0

2

2

2

21

ε

ρ

−=

∂

∂

−∇ t

V

c

V

L

Equation de Riemann pour V

j

A

A0

2

2

2

21

µ

−=

∂

∂

−∇ tcL

Equation de Riemann pour A

0

1

.2=

∂

∂

+∇t

V

cL

A

Equation de Lorenz

permet de retrouver la conservation de la charge et les équations de «!Heaviside-Hertz!».

La résolution des équations de propagations des potentiels avec terme source fournit les

expressions dites "aux potentiels retardés" :

∫∫∫ −

=

τ

ρ

πε

d

PM

cPMtP

tMV L)/,(

4

1

),(

0

∫∫∫ −

=

τ

π

µ

d

PM

cPMtP

tM L)/,(

4

),( 0j

A

Dans le cadre de l'approximation des régimes quasi-stationnaires où l’on néglige le retard

due à la propagation, les solutions aux équations de Riemann deviennent :

∫∫∫

≈

τ

ρ

πε

d

PM

tP

tMV ),(

4

1

),(

0

∫∫∫

≈

τ

π

µ

d

PM

tP

tM ),(

4

),( 0j

A

Maxwell et la théorie de la relativité

Maxwell sur les articles de Riemann et de Lorenz :

« From the assumption of both these papers we may draw the conclusions,

first, that action and reaction are not always equal and opposite, and second, that

apparatus may be constructed to generate any amount of work from its own

resources. For let two oppositely electrified bodies A and B travel along the line

joining them with equal velocities in the direction AB, then if either the potential or

the attraction of the bodies at a given time is th at due to their position at some

former time (as these authors suppose), B, the foremost body, will attract A

forwards more than B attracts A backwards. Now let A and B be kept asunder by a

rigid rod. The combined system, if set in motion in the direction AB, will pull in

that direction with a force which may either continually augment the velocity, or

may be used as an inexhaustible source of energy. »

James Clerk Maxwell, 1868.

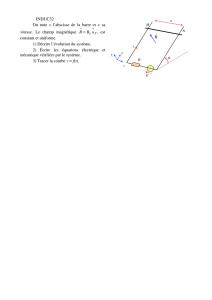

L’expérience de pensée de Föppl-Einstein

L’aimant bouge et le circuit est fixe :

un champ électrique est généré par

variation du flux magnétique à

travers la spire

Le circuit bouge et l’aimant est fixe :

un champ électromoteur est généré

par le mouvement du circuit dans

un champ magnétique

€

∂tB=-∇ × E

différent de

€

Em=v×B

=> Asymétrie pour Einstein

Albert Einstein 1905 ; John Norton, 2004.

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

1

/

23

100%

![[4] Susceptibilités](http://s1.studylibfr.com/store/data/003629260_1-3ca03b480b86418dfcd84dc43138f11a-300x300.png)