CHAPTER 3: Management History and Trends

60

The primary objective of this chapter is to provide the reader with a general

historical background on the fi eld of management. Many of the terms and

concepts noted in Chapters 1 and 2 have developed from classic and contem-

porary management theory and practice. If you have taken college courses in

business or management, the terms, concepts, and people noted in this chap-

ter should not be new to you. Before moving into the specifi c areas of external

environments, planning, organizational design, and human resource manage-

ment, it seems appropriate to explore the source of the current management

systems used to operate all organizations.

MANAGEMENT AS AN ART AND A

SOCIAL SCIENCE

A basic assumption of this text is that management is an art. In this case, an art

is typically defi ned as an ability or special skill that someone develops and applies .

Studying the theories of management, synthesizing the application of these

theories to a practical work environment, and then creating a workable system

for a specifi c organization require a tremendous amount of thought and effort.

It is often a lifetime job.

Management can also be considered to be a social science. Although the idea

of “science” in the workplace may not be very appealing to an aspiring arts

manager, the reality is that applying some of the techniques noted in this

chapter may help make a stronger arts organization.

As we will see, the general concept of scientifi c management is not universally

welcomed in the workplace. The term describes a particular approach to max-

imizing productivity by applying research and quantitative analysis to the

work process. The creation of general and specifi c management theories to

explain and predict how organizations and people behave is also integral to

thinking of management as a science.

At the center of any theory is the ability to predict an outcome if given a spe-

cifi c set of circumstances. A scientist develops a theory, conducts experiments,

establishes an outcome that can be repeated by others, and provides proof

of the theory. Management theory tries to achieve a similar goal: predictable

outcomes given controlled inputs. Unfortunately, the science of management,

as with any social science, is sometimes subject to unanticipated outcomes.

In management science, numerous other variables, including the behavior

of employees in the work environment, can quickly undermine a theory.

Applying the techniques used by social scientists can assist a manager in the

process of running an organization.

61

On-the-job management theory

When studying management theory and practice, which are often examined

by using case studies, it becomes apparent that many managers enter into the

practice of managing with virtually no theoretical background. Whether in the

arts or business, not having formal training has never been a barrier to running

an organization. For example, the late Katherine Graham, who once owned

the Washington Post, had no formal training in business management. The sud-

den death of her husband thrust her into the role of chief executive offi cer.

Nonetheless, she was able to successfully operate a major newspaper using her

personal abilities and adaptability. She was able to learn on the job and to fur-

ther develop her own operating theories and practices to maintain a success-

ful business. For every Katherine Graham there are many other people in the

workplace less successful at playing the role of manager. Your local bookstore

is stocked with readings about how employees should deal with the boss or

supervisor who does not seem to have mastered the art of managing. (For more

information about Katherine Graham go to: http://womenshistory.about.com/

od/journalists/p/katharinegraham.htm.)

In Chapter 2 we saw that Paul DiMaggio’s 1987 study for the National

Endowment for the Arts demonstrated more than 85 percent of the arts man-

agers in theaters, art museums, orchestras, and arts associations said that

they learned from on-the-job training.

1 The university-trained arts managers

surveyed claimed that their schooling did not adequately prepare them for

many of the demands of running an organization. The numbers of university-

trained arts managers has increased in the last few years, but it is still safe to

say that the experience of the workplace is required to complete the education

of any arts manager.

The effective manager

Regardless of how an individual learns the art and science of management,

an effective manager must eventually be able to analyze variables and pre-

dict outcomes based on experience. In other words, the manager must fi nd

a set of operating principles that can be used day to day. For example, an arts

manager might have to say to the Board, “If we raise prices, ticket orders will

decline based on discretionary spending patterns of our audiences. Or, if we

change our subscription plans, fewer people will order because any change

creates confusion. Or, if we perform nothing but concerts of modern music, a

signifi cant portion of our subscribers will stay home. ” These statements may

all be true and based on good scientifi c research, but that does not mean the

Board will follow the manager’s recommendation. It may be perfectly appro-

priate, given the mission, for an organization to make a decision that will

Management as an Art and a Social Science

CHAPTER 3: Management History and Trends

62

produce a negative outcome. An effective manager should be able to articu-

late her expectations of outcomes based on an understanding of the effects of

variables on particular decisions. Obviously, experience is and always will be

a great teacher.

To be an effective arts manager one should have an awareness and apprecia-

tion of the overall fi eld of management. The rest of this chapter focuses on

some of the major theories and principles that shape management today.

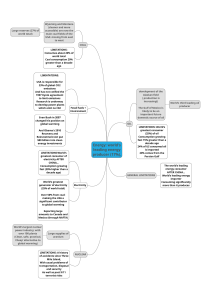

EVOLUTION OF MANAGEMENT THOUGHT

Preindustrialization

For the last several thousand years, organized social systems have managed the

resources needed to feed, house, and protect people. The evolution of man-

agement is intertwined with the development of the social, religious, and eco-

nomic systems needed to support cities, states, and countries. The church and

state provided the fi rst systems for planning, organizing, leading, and control-

ling. These management systems were predicated on philosophies that placed

people within complex hierarchies.

History provides many examples of management systems established by the

Egyptians, Romans, and Chinese. Many basic principles of supervision and con-

trol evolved from the projects undertaken by these societies. Building temples,

pyramids, and other massive structures required extensive management and

organizational skill. Organizing massive armies to go forth and conquer the

known world required detailed organizational planning and logistical coordi-

nation. Many modern management concepts expanded on the skill needed to

implement public works projects as the world shifted from an agrarian to an

industrial base.

A change in philosophies

The decline in the control of the Catholic Church in the fourteenth and fi f-

teenth centuries, and the subsequent religious struggles created by the rise

of Protestantism, slowly changed the fundamental relationship of people to

their governmental and religious systems. The seeds of the Protestant work

ethic were planted in the new order. The expansion of trade and the creation

of a permanent middle class grew out of the changes brought about by the

national and international economic systems.

The effects of the Renaissance and the Reformation extended far beyond redis-

covering the ideas and philosophies of antiquity. The development of new

political and social theories of government and management by such theorists

as Niccolo Machiavelli, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Adam Smith led to

1

/

3

100%