THEAT Jouluk 02_origtaitto.P65

1

THEATRE

FINNISH

FINLANDAIS

THEATRE

56

2002

FINNISH NATIONAL THEATRE 130 YEARS

LE 130E ANNIVERSAIRE DU THÉÂTRE NATIONAL DE FINLANDE

2

130ème anniversaire du théâtre

Le Théâtre National de Finlande célèbre cette année son

130ème anniversaire. Il a été le premier théâtre professionnel

originellement finnois de notre pays – avant sa création, les

Finlandais ne connaissaient le théâtre professionnel que par

les tournées des troupes étrangères.

L’activité du Théâtre National de Finlande a été ininterrom-

pue depuis sa création en 1872. C’est une longue durée pour un

théâtre, même à l’échelle européenne, et cela témoigne de sa

vitalité et de sa capacité de renouvellement artistique.

Les premières décennies de l’existence du théâtre finlan-

dais se sont passées à faire des tournées dans le pays tout en-

tier. Ces tournées ont inspiré la création de théâtres amateurs

locaux qui se sont transformés peu à peu en un réseau de

théâtres professionnels qui couvre tout le pays. Le nombre de

théâtres subventionnés par l’Etat et les municipalités s’élève

aujourd’hui à 59. Tous les théâtres professionnels finlandais

peuvent donc participer à la célébration avec le Théâtre Na-

tional de Finlande.

L’anniversaire est célébré dans toute la Finlande par

une campagne appelée Älyä elämää! Se livet! Cette campagne

s’adresse aux enfants et aux jeunes. Elle a pour objet d’amé-

liorer la connaissance et l’intérêt de ceux-ci à l’égard du théâ-

tre, d’augmenter la part de l’éducation dramatique dans l’en-

seignement artistique de base et d’accroître la coopération

des écoles et des théâtres.

Des ateliers dramatiques, des représentations pour la

jeunesse, des publications et des expositions seront au pro-

gramme de cette année. Une pièce amusante créée par de

jeunes professionnels du théâtre sera donnée dans des écoles.

Pour terminer les célébrations de l’anniversaire, les mi-

lieux du théâtre finlandais se réuniront aux Journées théâtra-

les nationales à la fin du mois de mai. Cette ancienne tradi-

tion de journées théâtrales sera reprise après une interruption

de dix ans – les questions fondamentales du théâtre et son

quotidien seront discutés à la fin des festivités.

✪

On parle beaucoup dans ce numéro du Théâtre National de

Finlande. Il faudrait bien plus de pages pour parler de ses

divers artistes. Les artistes choisis dans ce numéro représen-

tent également le répertoire actuel du Théâtre National.

Nous poursuivons également la présentation de la littéra-

ture dramatique finlandaise. Nous avons choisi cette fois deux

auteurs classiques modernes, Eeva-Liisa Manner et Mika

Waltari. Mika Waltari est renommé dans le monde entier

comme auteur du roman Sinouhé l’Egyptien, mais il est absolu-

ment inconnu à l’étranger comme auteur dramatique, car

aucune de ses pièces n’a été traduite dans d’autres langues.

Quant à Eeva-Liisa Manner, précurseur du modernisme fin-

landais, ses pièces ne sont toujours pas non plus connues à

l’étranger. Sa pièce tragique Poltettu oranssi (Orange foncé)

écrite en 1968, qui traite du bouleversement mental d’une

jeune fille, est d’une actualité encore plus grande aujourd’hui.

RIITTA SEPPÄLÄ

Directrice du Centre d’Information du Théâtre Finlandais

A Theatre’s Anniversary

This year the Finnish National Theatre is celebrating its

130th anniversary. It was the first professional theatre in the

country to emerge from our own Finnish cultural life - be-

fore that, the only professional performances seen here were

those by foreign groups if their tours ever reached Finland.

Since its founding in 1872 the National Theatre has

worked continuously. Even in European terms this is an ex-

ceptionally long age for any theatre and is proof of the thea-

tre’s vitality and capacity for artistic renewal and growth.

The Finnish Theatre, as it was then known, toured the

whole country during its first few decades. Its visits often

inspired people in the provinces to form local amateur

theatres. It was this which eventually grew into the network

of professional theatres we have around the country today,

59 ensemble theatres supported by either the state or by

individual towns. That is reason enough for the entire pro-

fessional theatre scene in Finland to join in the celebrations

with the Finnish National Theatre.

This anniversary is being marked across the country

through a campaign called Älyä elämää! Se livet! (‘See

Life’). The campaign is aimed at children and young people

and its principal goal is to create awareness of and interest

in the theatre, to strengthen the teaching of theatre in art

schools in addition to increasing the collaboration between

schools and theatres.

Throughout this anniversary year many theatre work-

shops, young people’s performances, publications and exhibi-

tions are being organised. A touring play has also been devised

for schools which tells the story of Finnish theatre history.

To end the celebrations, people working in theatres

from all over the country will come together at the Theatre

Days. This long tradition of the national theatre meeting is

being revived after a ten year break - to round things off

there will be a discussion about the fundamental questions

of theatre, the everyday of the theatre, which is not always

call for celebration.

✪

In this edition we discuss the National Theatre rather a lot.

It would require many more pages if we were to talk about

its multifaceted group of artists. Certain figures have been

brought into focus to give an overview of the National

Theatre’s current programming.

We are also continuing our presentation of Finnish plays

and playwrights. In this edition we have featured two classic

modern writers, Eeva-Liisa Manner and Mika Waltari.

Waltari is well-known throughout the world as the author of

Sinuhe, the Egyptian, but outside Finland he is unknown as a

playwright, because there are currently no translations of his

plays. The pioneer of Finnish modernism, Eeva-Liisa Man-

ner, is still awaiting her international ‘breakthrough’. Her

1968 play A Burnt Orange, the tragic story of a young girl’s

mental problems, still resonates to this day.

RIITTA SEPPÄLÄ

Director of the Finnish Theatre Information Centre

3

Publisher Editeur Finnish Theatre Information Centre Centre d’Information du Théâtre Finlandais

President Présidente : Raija-Sinikka Rantala

Director Directrice : Riitta Seppälä

Adress Adresse : Teatterikulma, Meritullinkatu 33, 00170 Helsinki Finland Tel. +358-9-135 7887, fax 135 5522

e-mail [email protected] Internet www.teatteri.org

Editor Rédactrice Anneli Kurki

Translations David Hackston, Traductions Gabriel de Bridiers

Art Director Heikki Vanhatalo ISSN 1238-6057 Printed by Erweko

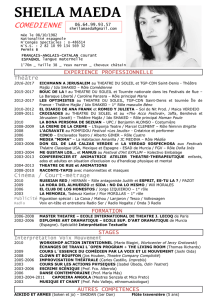

Cover photo :

Finnish National

Theatre, big stage.

Photo: Arno de la

Chapelle.

IN THIS EDITION

DANS CE NUMÉRO

Couverture

Théâtre National de

Finlande,

la grande scène.

18-21

lPentti Siimes has had a long and distin-

guished career as an actor at the National

Theatre and has also reached wider audi-

ences through his roles for television. Profes-

sor Irmeli Niemi assesses Siimes’ work.

lPentti Siimes a fait une carrière d’acteur

magnifique au Théâtre National et il a

également été découvert par le grand public

grâce à ses rôles à la télévision. Le professeur

Irmeli Niemi en fait un portrait.

22-24 lMika Waltari is known throughout the

world as the writer of Sinuhe, the Egyptian.

He is also a notable playwright. The re-

searcher Hanna Suutela writes about

Waltari’s work as a playwright.

lMika Waltari est mondialement connu

comme auteur de Sinouhé l’Egyptien. Il a

toutefois été également un auteur

dramatique important. La chercheuse

Hanna Suutela écrit sur l’œuvre dramatique

de Waltari.

25-27

lEeva-Liisa Manner was a poet and a playwright, the pioneer of

Finnish modernism. Here the editor of the magazine Books from

Finland, Soila Lehtonen, discusses Manner’s plays.

lEeva-Liisa Manner était poète et auteur dramatique, l’un des

précurseurs du modernisme finlandais. Soila Lehtonen, rédactrice

de Books from Finland écrit sur les pièces d’Eeva-Liisa Manner.

PAGE

page

4-5

lThe National Theatre is 130 years old. To celebrate this an-

niversary, the wonderfully renovated theatre has been reo-

pened.

l130ème anniversaire du Théâtre National de Finlande. Le

théâtre magnifiquement rénové a été réouvert à l’occasion des

festivités.

6-8

lThe National Theatre as my Des-

tiny: Artistic director Maria-Liisa

Nevala writes about her thoughts on

the role of the nation’s main stage.

lThéâtre National de Finlande, mon

destin. La directrice Maria-Liisa

Nevala écrit sur la mission de la scène

principale finlandaise.

9-14 lActor Portraits from the National

Theatre: the critic Outi Lahtinen intro-

duces some of this season’s actors.

lImages d’acteurs du Théâtre Na-

tional. La critique Outi Lahtinen écrit

sur la personnalité des interprètes du

répertoire de cette saison.

15-17

lKatariina Lahti has directed some

marvellous interpretations at the Na-

tional Theatre, most recently Ibsen’s A

Doll’s House. Outi Lahtinen discusses

Katariina Lahti’s work.

lKatariina Lahti a fait des mises en

scène splendides au Théâtre National,

dont la plus récente est celle de La

Maison de poupée d’Ibsen. Outi

Lahtinen écrit sur l’œuvre de

Katariina Lahti.

FINNISH THEATRE FINLANDAIS

4

The year 2002 marks the

hundred and thirtieth anni-

versary of the foundation of

the Finnish-language theatre

which was eventually to be-

come the Finnish National

Theatre. It also marks the

hundredth anniversary of

the majestic, neo-romantic,

grey granite edifice which

houses it. Both these events

are being celebrated with

important festivities and

productions.

When the Finnish Theatre was founded in

1872 by Kaarlo and Emilie Bergbom, its

troupe consisted of eight members. This

number grew to fourteen by the following

year, when the company had twenty seven

plays in its repertoire. The theatre’s origi-

nal agenda was to spend three months of

the year in Helsinki, and the rest of the

year touring Finland. At this time Helsinki

was a predominantly Swedish-speaking

area, and the Bergboms’ goal was to bring

theatre to the Finnish-speaking provinces.

To pay tribute to this early heritage, the

Finnish National Theatre has included in

this year’s season a tour of five Finnish cit-

ies, with four separate productions: Ten-

nessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,

Francis Veber’s Le Diner de Cons, Marcel

Pagnol’s Topaze and a double bill of

Nikolai Koliada’s one-act plays Persian Lily

and Cry-baby. This venture has proved an

outstanding success. In the city of Pori,

the demand for tickets was so great that

the theatre had to erect an out-door screen

on which the play was projected for the

huge public sitting outside on the grass,

like at a rock concert.

The Finnish Theatre pursued its prac-

tice of touring the country until it moved

into its permanent home in 1902, after

which this activity gradually decreased.

On its opening, the building was the first

purpose-built Finnish-language theatre in

the country, and one of the grandest theat-

rical establishments in Northern Europe.

In honour of its centenary, the building

has been undergoing major refurbishment

since January 2000. This is the first time

in the history of the theatre that the main

stage has been closed to the public. When

the theatre reopened in autumn 2002, the

building represented a harmonious blend

of artistic tradition and modern technol-

ogy. The stage is be-

ing radically updated

with modern sound,

lighting and technical

equipment, but not

at the expense of the

historic architecture.

The project’s chief

architect Sari Schul-

man has worked

closely with director

Maria-Liisa Nevala in

the common goal of

meeting the needs of

modernisation with-

out compromising

the style and spirit of the original design.

Schulman’s research began as early as

1998. She has slowly explored the many

superficial layers imposed over the last cen-

tury, in order to discover the original struc-

tures and surfaces. As much as possible of

the interior is restored to its former glory by

Schulman’s team of historians and specialist

craftsmen. The project had a budget of

around 37 million Euros.

The renovated main stage began its

new season with a revival of one of Fin-

land’s great classic comedies Nummisuu-

tarit (‘The Cobblers of the heath) by

Aleksis Kivi, first produced in 1875, just

three years after the founding of the

Finnish Theatre. Kivi is considered to be

the first writer to create a Finnish literary

language, and his plays marked a break-

through for Finnish drama. In a recent

poll among leading cultural figures,

Nummisuutarit was still considered the

most significant Finnish-language play

ever written. It is directed by the theatre’s

in-house director, Antti-Einari Halonen.

Productions for the smaller stages include

Eugene Ionesco’s Les Chaises and La Lecon

in a double-bill directed by Otso Kautto,

as well as Igor Bauersima’s norway.today,

directed by Anna-Elina Lyytikäinen.

A new play Ystäväni by the young

Finnish writer Jari Järvelä had a première

also in the autumn. There was also a new

adaptation of a favourite Finnish chil-

dren’s classic for the youngest generation

of theatre goers. The theatre continues to

be committed to young audiences and

artists alike, commissioning new plays

from budding writers and offering a wide

range of job opportunities to recently

qualified artists in all fields of theatre

work. It is fitting that Finnish drama, both

new and old, is strongly represented in this

season’s repertoire, in celebration of the

refurbished theatre’s grand opening.

4

4

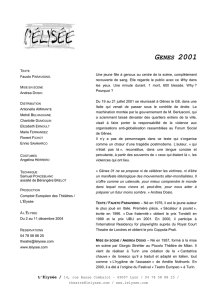

● Maria Kuusiluoma in norway.today at the National Theatre,

directed by Anna-Elina Lyytikäinen.

● Maria Kuusiluoma dans norway.today, mise en scène

Anna-Elina Lyytikäinen.

Photo: Leena Klemelä.

THE FINNISH NATIONAL

THEATRE IN 2002

THE FINNISH NATIONAL

THEATRE IN 2002

5

grande comédie classique du répertoire

finlandais, Nummisuutarit (Les Cordon-

niers sur la butte) d’Aleksis Kivi, crée en

1875, trois ans après la fondation du

Théâtre Finlandais. Kivi est considérée

comme le créateur de la langue littéraire

finnoise et ses pièces ont marqué la percée

du théâtre finlandais. Dans un récent

sondage parmi des personnalités impor-

tants de la culture. Nummisuutarit était

encore considérée comme la pièce la plus

significative du théâtre de langue finnoise.

Elle sera mise en scène par Antti Einari

Halonen, metteur en scène associé au théâ-

tre. Les productions pour les petites scènes

sont Les Chaises et La Leçon d'Eugene

Ionesco dans un programme double mis

en scène par Otso Kautto et norway.today

d’Igor Bauersima mis en scène par Anna-

Elina Lyytikäinen.

Une nouvelle pièce du jeune auteur

finlandais Jari Järvelä etait presentée à

l’automne. Pour la jeune génération de

spectateurs, il y a aussi une nouvelle

adaptation d’une piène finlandaise pour

enfants très populaire.Le théâtre reste

attaché aussi bien au jeune public qu’aux

jeunes artistes. Il continue de faire des

commandes à de jeunes auteurs et offre

des opportunités de travail à de jeunes

professionnels dans tous les domaines du

théâtre. C’est certain que le théâtre finlan-

dais, à la fois récent et ancien, sera forte-

ment représenté dans le répertoire du théâ-

tre de les saisons prochaines, en célébration

de la réouverture du théâtre rénové.

● Ystäväni (My Friend) by Jari Järvelä at the National Theatre, directed by Maarit Ruikka. On the photo Päivi Akonpelto and

Tommi Eronen

● Ystäväni ( Mon ami) de Jari Järvelä au Théâtre National, mise en scène Maarit Ruikka. Sur la photo Päivi Akonpelto et

Tommi Eronen. Photo: Leena Klemelä.

5

5

L’année 2002 marque le

130e anniversaire de la

création du Théâtre Finnois,

premier nom du théâtre qui

deviendra Théâtre National

de Finlande. Cette année

marque également le 100e

anniversaire du majestueux

et néoromantique édifice en

granit gris qui l’abrite. Ces

deux événements sont célé-

brés par des festivités et

des productions importan-

tes.

À la fondation du Théâtre Finnois par

Kaarlo et Emilie Bergbom en 1872, la

troupe comptait huit membres. Ce chiffre

atteint douze l’année suivante et la com-

pagnie présente vingt-sept pièces à son

répertoire. À l’origine, le théâtre passait

trois mois de l’année à Helsinki et le reste

du temps en tournée dans toute la Fin-

lande. À cette époque, Helsinki était une

région dominée par la langue suédoise et

le but des Bergbom était de porter le

théâtre dans les provinces de langue fin-

noise. Pour rendre un hommage à ce pre-

mier héritage, le TNF a prévu pour cette

saision la tournée de quatre productions

dans cinq villes finlandaises : Une chatte

sur un toit brûlant de Tennessee Williams,

Le Dîner de Cons de Francis Veber, Topaze

de Marcel Pagnol, et un programme dou-

ble des pièces en un acte de Nikolai

Koliada, Persian Lily et Cry-baby. Cette

aventure a été couronnée d’un grand suc-

cès. Dans la ville de Pori, la demande de

places était si forte que le théâtre a dû

irrigé un écran géant sur leguel était pro-

jetée la pièce pour un immense public

assis à l’extérieur sur les pelouses, comme

pour un concert de rock.

Le Théâtre National de Finlande a

poursuivi son activité de tournées jusqu’à

son installation dans son lieu définitif en

1902, après quoi cette activité a décrue.

À son ouverture, ce bâtiment était le pre-

mier véritable théâtre de langue finnoise

du pays et un des plus grands établisse-

ments théâtraux de l’Europe du Nord.

Pour honorer ce centenaire, le bâtiment a,

depuis janvier 2000, bénéficié de grands

travaux de rénovation. C’est la première

fois dans l’histoire du thèâtre que la grande

scène a été fermée au public. Quand le

théâtre a rouvert ses portes à l’automne

2002, le bâtiment etait le reflet d’un mé-

lange harmonieux de tradition artistique

et de technologie moderne. La scène a été

radicalement rénovée avec une sonorisa-

tion, des lumières et des équipements tech-

niques modernes, mais pas au détriment

de l’architecture d’origine. L’architecte en

chef, Sari Schulman a travaillé en étroite

collaboration avec la directrice, Maria-

Liisa Nevala, dans le but commun de

répondre aux besoins de modernisation,

sans compromettre le style et l’esprit du

design d’origine. Les travaux entrepris par

Sari Schulman on débuté dès 1998. Elle a

lentement exploré les nombreuses couches

superficelles imposées par le siècle passé

afin de découvrir les structures et les surfa-

ces des origines. Le bâtiment intérieur a

été restoré au maximum à l’image de sa

gloire passée par Schulman et son équipe

d’historiens et d’artisans. Le projet avait

un budget de 37 millions d’euros.

La grande salle rénovée a ouvert la

nouvelle saison avec la reprise d’une

LE THÉÂTRE NATIONAL DE

FINLANDE EN 2002

LE THÉÂTRE NATIONAL DE

FINLANDE EN 2002

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

1

/

28

100%