resistance aux antibiotiques : un probleme mondial

RESISTANCE

AUX ANTIBIOTIQUES :

UN PROBLEME MONDIAL

Colloque parrainé par la Société

de Pathologie Infectieuses de Langue Française (SPILF)

VOLUME DES RESUMES

Comité scientifique : O. BOUCHAUD, S. BLANCHY, J. DELMONT, F. GAY- ANDRIEU

Page 2/13 Résistance aux antibiotiques : un problème mondial

Mercredi 11 décembre 2013

Colloque organisé par la Société de Pathologie Exotique, parrainé par la Société de Pathologie Infectieuse de Langue Française

Centre d’Information Scientifique, Institut Pasteur Page 3/13

Sommaire

(pagination à refaire en attente du résume Mme Cambau)

Introduction : Gènes sans frontières............................................................................... 4

Patrice COURVALIN (Institut Pasteur de Paris)

Résistance et multirésistance : vers l’impasse thérapeutique ? .......................................... 4

Vincent JARLIER (CNR des mycobactéries et de la résistance aux antituberculeux)

Antibiorésistance en Afrique sub-saharienne : l’expérience de l’Hôpital National de Niamey.... 5

Eric ADEHOSSI (Hôpital National de Niamey)

La place du laboratoire de biologie médicale dans la lutte contre la progression des

résistances aux ATB dans les pays en développement. ...................................................... 6

Christophe LONGUET (Fondation Mérieux)

Les bactéries multirésistantes d’importation : épidémiologie, risques pour les hôpitaux du

nord. ......................................................................................................................... 6

Antoine ANDREMONT (APHP - Hôpital Bichat)

Enjeux de santé publique associé à l’usage des antibiotiques en production animale dans les

PED et résistance aux antibiotiques. .............................................................................. 7

Pascal SANDERS (Anses)

Les bactéries résistantes entre savoir et pouvoir : épistémologie et sociologie d'une impasse

médicale. ................................................................................................................... 8

Quentin RAVELLI (CNRS - Sociologie)

Situation globale des tuberculoses MDR et XDR. Surveillance, évolution observée,

perspectives et défis. ................................................................................................... 9

Thierry COMOLET (Médecins inspecteur de santé publique)

La collaboration internationale bien pensée peut-elle (a-t-elle pu) enrayer l’avance de

la tuberculose multi-résistante (TB-MR) ? ..................................................................... 11

Léopold BLANC (ex-coordonateur des opérations pour la tuberculose à l’OMS)

La prise en charge des cas de tuberculose multi résistantes importées en France. .............. 11

Damien LE DÛ (Centre hospitalier de Bligny, Sanatorium)

Résistance aux antilépreux : comment la détecter et la surveiller ?................................... 12

Emmanuelle CAMBAU (APHP Lariboisière)

Protéger les antibiotiques, une ressource précieuse : rôle de l’alliance contre les bactéries

multirésistantes. ....................................................................................................... 13

Jean CARLET (ACdeBMR World Alliance against Antibiotic Resistance)

Page 4/13 Résistance aux antibiotiques : un problème mondial

Mercredi 11 décembre 2013

Introduction : Gènes sans frontières

Patrice COURVALIN

Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

Since the beginning of the antibiotic era, ca. sixty years ago, bacteria pathogenic for mammals have

evolved towards resistance and, in many instances, multi-resistance. In contrast with this continuous

evolution there has been during the last two decades diminished research to discover and develop new

antibacterial agents. This contrasting tendency has led to an important decrease in therapeutic options

and is particularly worrying if one considers that more than ten years are necessary to develop a new

antibiotic. There are three levels of resistance dissemination depending upon the vector: bacteria (clonal

spread), replicons (plasmid epidemics), or genes (transposon epidemics). These various levels of

dissemination, which co-exist in nature and thus account for the extraordinary rise in antibiotic resistance

among bacteria, are not only infectious but also exponential since each is associated with DNA duplication.

Clonal dissemination is associated with chromosome replication, plasmid conjugation with replicative

transfer, and gene migration with replicative transposition. Regardless of the mechanism of action of a

drug class, one must realize that resistance already occurs in nature or will inevitably emerge. This is,

perhaps, obvious for natural antibiotics, as the producing organisms must avoid self destruction, but it

also holds true for non-natural drugs. It is thus clear that bacteria are able to resist every antibiotic,

naturally or in an acquired fashion, and selection of resistant bacteria can be regarded as the ultimate

criterion for activity of an antibiotic. In addition, resistance, either by mutation or after acquisition of

foreign genetic information, will not disappear. As dissemination of resistance is closely linked to the

magnitude of the selective pressure, the only hope is to delay this dissemination. This stresses the

importance of the prudent use of these molecules.

Résistance aux antibiotiques : vers une

catastrophe écologique et sanitaire ?

VINCENT JARLIER

Bactériologiste, Université Paris 6, Faculté de Médecine Pierre et Marie Curie

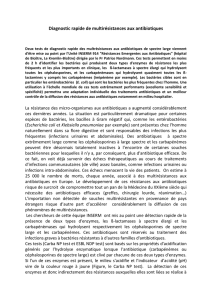

La menace que représente la résistance aux antibiotiques, et son stade ultime l’impasse

thérapeutique (très peu ou plus d’antibiotiques encore efficaces), est évidente lorsqu’elle

concerne de grandes maladies bactériennes contagieuses comme la tuberculose (tuberculose

MDR : résistante à l’isoniazide et à la rifampicine), la typhoïde (bacille de la typhoïde résistant

aux ß-lactamines et aux fluoroquinolones…) ou les infections génitales à gonocoques (résistant

aux ß-lactamines, aux fluoroquinolones, aux cyclines et à l’azithromycine…). En effet, les

conséquences médicales de la résistance sont alors immédiates en raison des grandes difficultés

thérapeutiques qui en découlent. La résistance est, en revanche, beaucoup moins visible

lorsqu’elle concerne les bactéries qui peuplent de manière permanente et normale (bactéries

« commensales ») notre tube digestif (environ 100 milliards par gramme de selles, dont les

colibacilles), notre rhinopharynx (environ 100 millions de par millilitre de sécrétion, dont les

staphylocoques dorés) et notre peau.

Les antibiotiques ont une caractéristique singulière : ils n’agissent pas sur l’homme (au contraire

des médicaments de l’hypertension, du diabète…) mais sur les bactéries. Ils agissent d’abord, ce

qui est le but, sur les bactéries du foyer infectieux bactérien diagnostiqué (ou suspecté) qui sont

en général peu nombreuses (quelques millions en tout). Mais ils agissent aussi sur nos

innombrables bactéries commensales, ce qui est un effet secondaire indésirable mais inévitable.

Sous l’effet de l’antibiotique, les rares bactéries commensales qui portent des mécanismes de

résistance (mutations, acquisition de gènes provenant d’autres bactéries) prolifèrent et

remplacent les bactéries sensibles.

Colloque organisé par la Société de Pathologie Exotique, parrainé par la Société de Pathologie Infectieuse de Langue Française

Centre d’Information Scientifique, Institut Pasteur Page 5/13

Les bactéries ainsi « sélectionnées » peuvent être transmises à d’autres personnes (transmission

croisée). Elles peuvent aussi transférer les gènes qui codent pour leurs mécanismes de

résistance à des bactéries sensibles, qui deviennent résistantes à leur tour.

On sait, par exemple, que les bactéries intestinales résistantes (ex. : colibacilles producteurs de

ß-lactamases à spectre étendu ou BLSE) diffusent au sein d’une même famille, d’un service

hospitalier et dans les eaux des égouts, en particulier celles des hôpitaux puis les stations

d’épuration, dont les résidus sont utilisés comme fertilisants agricoles et les effluents liquides

déversés dans les cours d’eaux, ce qui expose au retour vers l’homme par les aliments et l’eau.

Le même phénomène « pression de sélection - transmission croisée » se produit au sein du

bétail recevant des antibiotiques à titres curatif, préventif ou pour améliorer la prise de poids

(« promoteurs de croissance »).

Les bactéries commensales résistantes qui diffusent dans la population humaine et animale et

l’environnement ne sont pas visibles. Elles constituent la partie souterraine de la menace dont on

ne prend conscience que lorsqu’un événement favorise le développement d’une infection

« opportuniste » à partir de ces bactéries : grossesse, adénome de la prostate ou pose d’une

sonde urinaire à l’hôpital pour les infections urinaires à colibacille BLSE ; brûlure, blessure ou

intervention chirurgicale pour les infections cutanées à staphylocoque doré résistant à la

méticilline (SARM).

En résumé, la pression de sélection par les antibiotiques et la transmission croisée sont les deux

facteurs qui alimentent la résistance bactérienne. Soumises au « cycle infernal » « pression-

transmission-pression », les bactéries accumulent des mécanismes de résistance à de nombreux

antibiotiques (multirésistance) au fur et à mesure de leur introduction en médecine humaine et

vétérinaire. Si l’on veut sauvegarder l’activité des antibiotiques existants (la mise au point de

nouvelles molécules est devenue très aléatoire) qui ont sauvé tant de vies et constituent

l’héritage des générations à venir, il nous faut au plus vite interrompre ce cycle infernal en

réduisant massivement les volumes d’antibiotiques utilisés chez l’homme et l’animal et lutter

contre la transmission des bactéries résistantes en améliorant l’hygiène à l’hôpital, dans les

collectivités (écoles…) et la population générale. En raison des quantités phénoménales de

bactéries intestinales qui jouent le rôle de «creuset» de la résistance, il faut aussi

impérativement améliorer le traitement des eaux usées et contrôler leur « recyclage » vers les

cours d’eau et l’usage agricole. Il faut enfin contrôler le réservoir de bactéries multirésistantes

provenant des animaux d’élevage destinés à la consommation humaine. La lutte contre la

résistance bactérienne est typiquement une question de développement durable au même titre

que la prévention du réchauffement de la planète et la déforestation.

LA RESISTANCE AUX ANTIBACTERIENS EN AFRIQUE

ADEHOSSI Eric

Médecine Interne, Faculté des Sciences de la Santé de Niamey

La résistance aux antibiotiques est la capacité d'un micro-organisme à résister aux effets des

antibiotiques.

Ce phénomène constitue un problème grave qui touche l’essence des activités de lutte contre les

maladies infectieuses, et peut mettre un frein aux progrès accomplis dans ce domaine. Bien qu’elle

constitue une réaction naturelle aux microbes, la résistance peut être endiguée par un recours prudent

et approprié aux antibiotiques.

Bien que l’utilisation excessive des antibiotiques ait été la principale cause de la résistance dans les

pays développés, ce seul phénomène ne peut expliquer l’émergence croissante des microorganismes

résistants dans le monde en développement.

Les facteurs favorisants la résistance en Afrique sont liées aux ressources humaines, à l’hygiène, au

diagnostic inapproprié avec pour conséquence une sur utilisation des antibiotiques, aux mauvaises

pratiques en matière de prescription d’ordonnance, à la vente non réglementée de médicaments et

l’absence de programme de lutte contre les infections.

D’où la nécessité d’une réforme croissante avec la mise en place d’une surveillance bactériologique, à

la mise en place et à l’application stricte d’une réglementation sur les antibiotiques.

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

1

/

13

100%