Reflexivity, Paradoxes, and Double Binds: An Alternative Theory

Telechargé par

peruwelzbonsecours

Fam Proc 21:91-112, 1982

Paradoxes, Double Binds, and Reflexive Loops: An Alternative

Theoretical Perspective

VERNON E. CRONEN, PH.D.a

KENNETH M. JOHNSON, PH.D.b

JOHN W. LANNAMANN, M.A.c

aAssociate Professor, Department of Communication Studies, Machmer Hall, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts

01002.

bAssistant Professor, Department of Speech and Drama, Division of Speech Communication and Human Relations, University of

Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

cTeaching Associate, Department of Communication Studies, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts.

This article presents a new theory of refiexivity in systems of social meaning and action. It is argued that Russell's

Theory of Logical Types, which formed the basis of the early work of the Palo Alto group, rests upon an inappropriate

and largely outdated epistemology. The theory offered here rejects the assumption that reflexivity and paradox are

coterminous. It is further argued that reflexivity is a natural and necessary feature of human systems of meaning. New

analytic tools are offered for discerning problematic from nonproblematic reflexive loops. The new tools take the form of

a symbol system that can be used to represent the rules that organize reflexive relationships. The theory also contains a

set of statements designed to delimit conditions under which problematic reflexive loops have ramifications for persons'

mental health.

Ever Since Epimenides of Crete said that "all Cretans are liars," scholars interested in the logic of language and thought

have had to contend with the phenomenon of reflexivity. And ever since Bateson's (7) work on metacommunication and

double bind, scholars interested in family interaction have been intrigued, perplexed, and sometimes frustrated by the

possible relevance of reflexivity for their field of study. Although the phenomenon of reflexivity (and the special case of

paradox) is a particularly difficult topic for research, modern trends in social science impel us to deal with it. In place of

reductionistic accounts, recent studies indicate that social meanings are context-dependent (18, 49). It is no longer

controversial to contend that a message is given meaning by reference to the context in which it appears. However, once the

social scientist chooses the perspective of hierarchically organized systems of meaning, he or she must then contend with

the structural complexities of hierarchical systemsone of which is the tendency for systems to exhibit "tangles" or "loops"

among levels (28).

One of the most influential accounts of hierarchical relationships is the one developed by Bateson and elaborated into a

theory of communication and family therapy by the Palo Alto group (58, 59, 60). The Palo Alto group put forward the now

famous double-bind theory of schizophrenia (7). At the heart of that theory is the idea that paradox, or the confusion of

hierarchically ordered levels of meaning, is a persistent quality of the communicative milieu that produces schizophrenia.

The conditions that create a double bind may be summarized as follows: (a) the individual is involved in an intense

relationship, one in which he or she feels it is important to discriminate accurately; (b) the other party to the relationship is

expressing two orders of message and one order denies the other; (c) the individual is prevented from commenting upon the

discrepant messages so as to resolve the inconsistency; (d) the individual is prevented from leaving the field; and (e) the

individual comes to perceive his or her universe in double-bind patterns. Unfortunately, research has been anything but

overwhelming in providing support for the double-bind theory of schizophrenia. In an excellent review, Olson (41)

observed that much of the research has been poorly designed or misinterprets the double-bind theory. But Olson also notes

that much responsibility for the state of research lies in the present formulation of double-bind theory itself. Olson calls it

"so abstract that it is elusive" (p. 80). Indeed, it is even elusive for experts in double-bind theory. Ringuette and Kennedy

(48) found very low interjudge reliabilities among expert judges closely involved in the development of the concept who

were asked to identify double-bind messages (r = .19). The debate over the predictive power of double-bind theory has

continued since Olson's review (13, 19, 30). Some scholars argue that paradox can have the beneficial effects of

establishing self-identity (31) and enhancing creativity (65). Winston (62) and Harris (21) point out that paradox seems to

be a ubiquitous phenomenon in family relationships, and Bateson himself (3) has taken the view that paradox may produce

beneficial as well as harmful effects. Thus, although paradox is an intriguing concept, its function in family communication

seems less clear to us now than it did when Bate-son et al. first propounded their theory almost twenty-four years ago.

We believe that the problems researchers have encountered are owing to problems in the conception of paradox itself

and that these problems go beyond the need for clarification. We propose in this paper to take a new look at the concept of

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1

paradox or reflexivity in hierarchical systems. We prefer the less pejorative term "reflexive loop" because we propose to

show that although paradoxes are indeed reflexive loops, only certain subclasses of loops are problematic for social actors.

Specifically, we will do the following: First, we will briefly review the basic concept of reflexivity itself, limiting our

discussion to the relevance of the concept for social action. Second, we will discuss the connection between the original

Palo Alto group's concept of reflexivity and Russell's Theory of Logical Types. In the third section we begin the

presentation of our own formal theory by offering a set of propositions that recast current knowledge about the general

nature of reflexive relationships. Section four continues the development of our position by introducing a new way to

distinguish problematic from nonproblematic reflexive loops. Presentation of our position is concluded in section five

which puts forward ways of distinguishing the conditions under which problematic reflexive loops may have implications

for persons' mental health. The paper concludes with a discussion of implications for research and clinical application.

WHAT IS REFLEXlVlTY?

The concept of reflexivity came to family relations and communication through the work of Bateson and his associates in

the Palo Alto group. Bateson argued that communication involves two 1evels of meaning: (a) a "command" or "relational"

level and (b) a "report" or "content" level. The two levels are said to have a hierarchical organization such that the relational

level forms the context for interpreting the content level. In his now classic analysis of monkeys at play in the Fleishhaker

Zoo, Bateson described how the relational level message "this is play" functions to alter the denotative or content level

meaning of a nip. Paradox is said to occur when the two levels of meaning are "confused."

We can say, as does Hofstadter (28), that when two or more levels in a system are unclear as to which is of higher level,

a reflexive loop is formed. In Hofstadter's words, reflexivity exists when "by moving upwards (or downwards) through the

levels of some hierarchical system, we unexpectedly find ourselves right back where we started" (p. 10). One classic

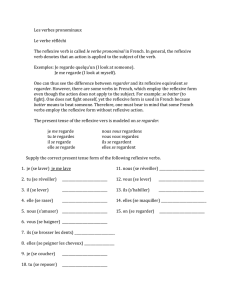

example of a reflexive loop is shown below:

The statement in the box is simultaneously about statements in the box (higher level message), and it is the statement in

the box. Thus by moving down from the statement about what is in the box, we find ouselves back at the same statement.

That is a simple one-step reflexive loop. It has the same form as other famous paradoxes including Epimenides' paradox

cited earlier and the reflexive statement "This sentence is false." A visual representation is provided in Figure 1. A more

complex reflexive loop is produced when two messages are simultaneously context (higher level) and that which is within a

context (lower level) in the same system. Watzlawick et al. (59) discuss the loop formed when a child encounters the words

"l love you" said in a sarcastic tone. If the child does not know which message (the content or the tone) is at the higher level,

the child is confused. If the tone is treated as the higher level, the words' denotative meaning is discounted, but if the words

are treated as the higher level, the tone must be discounted (see Fig. 1).

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2

Figure 1.

Examples of one-and-two-stage reflexive loops

Bateson's essential insight was that communication can be treated as a hierarchical system and that social meanings like

other hierarchical systems may exhibit reflexive loops. That is a provocative and enduring contribution. Problems stem

from relying on Russell's Theory of Logical Types (5) for analyzing reflexive loops.

THE PALO ALTO GROUP AND THE THEORY OF LOGICAL TYPES

The Theory of Logical Types is essentially an attempt to deal with reflexive loops by prohibiting them. The creation of a

system of meaning that contains such loops is considered a mistakea confusion of logical types. That is explicitly the

position taken by some of Bateson's followers1 in the Palo Alto group (60). Russell's work was designed to rid mathematics

of the problem of paradox by recourse to the principle: "A class cannot be a member of itself." In other words, an element

within a context must not loop back upon itself.

To understand why Russell would attempt to abolish reflexivity by fiat, we must briefly examine the philosophic tradition

of which Russell was a part. The Theory of Logical Types was a key precursor to the early work of Russell's famous

student, Wittgenstein. A unifying thread that runs through Whitehead and Russell's Principia Mathematica (61) and

Wittgenstein's Tractatus (64) is that the proper role of language is to represent the natural order-the levels of organization

"out there"in a way that does not lead to nonsense or confusion (55, pp. 400-413). The idea that language must form a

picture of external reality led Wittgenstein to posit that each symbol on the language-based map of reality must correspond

to a unit in reality or express a relationship among those symbols. The "reality" pictured was, in the Newtonian tradition,

not a chaotic or confused nature beset by strange loops, but a perfect, natural order (63, 64). Thus, making sense

presupposes an "untangled" orderly reality to make sense about. The construction of reflexive, or tangled hierarchies, is

then either an act of confusing reality or the tacit assertion that reality itself is nonsensical and clear communication

impossible.

It is interesting to observe that later in his career Russell admitted the arbitrary nature of his Theory of Logical Types. G.

Spencer Brown (12, p. ix) reports Russell's reaction to the book Laws of Form in which Brown attacks Types Theory: "To

my relief, he was delighted. The theory was, he said, the most arbitrary thing he and Whitehead had ever had to do, not

really a theory but a stopgap...." Wittgenstein, of course, later rejected his own picture theory (63). Bateson himself came to

reject the idea of discrete levels of organization. In his last work Bateson described levels of meaning in human systems as

"a hierarchy of orders of recursiveness" (5, p. 201). Strangely, the Palo Alto group has held to a view of reflexivity rejected

by its own creators. The philosophic rationale for simply banning loops rests on the assumptions that: (a) the role of natural

language is to picture external reality; (b) external reality exhibits discrete levels of organization free from loops or tangles;

and (c) communication that confuses levels of organization (logical types) is destructive of clear representation.

The original work of the Palo Alto group imposes a further restriction on the Theory of Logical Types itself. Although

Bateson's conception of the levels of learning (4) implies multiple levels of cognition, his work on play and fantasy

discusses only two levels of meaning, content and relationship. The subsequent work of Watzlawick and his colleagues

focuses exclusively on those two levels and the relation between them. The product of merging that two-level view of

communication with logical typing is a focus on analyzing "confusions" between levels in what are assumed to be two-level

systems.

REFLEXIVITY IN SYSTEMS OF SOCIAL MEANING

Part I: A Recasting of Current Knowledge

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

3

The Russellian concept of refLexivity provides the backdrop for what follows: a systematization of current research and

theory about reflexivity in hierarchical systems of meaning and action. The definitions, postulate, propositions, and

corollaries below are deceptively simple and most of them noncontroversial, but together they form a dramatic contrast with

the Russellian position.

Postulate: Systems of meaning and action are persons cognitive constructions of their social realities and not best

assessed as reflections of external realities. This postulate endorses the "new view" of communication that has arisen in

the twentieth century. The new view is that communication is not best conceived as the vehicle for picturing external reality

and conveying undistorted pictures from one person to another. The modern view is that communication is the process by

which persons create social realities. As Austin (1) observed, a marriage is not a natural phenomenon but a significant,

socially created institution. The enactment of marriage is, of course, not to be judged by its faithfulness to "true," "natural"

marriage. Truth standards are inappropriate, but standards of felicity, utility, and satisfaction are appropriate. The roots of

the modern view are to be found in several disciplines: in philosophy in the later work of Wittgenstein (63), Austin (1), and

Langer (20); in sociology in the work of George Herbert Mead (39) and Berger and Luckmann (9); and in anthropology in

the work of Malinowski (37).

Although Watzlawick employs the Theory of Logical Types to analyze paradox, he is explicit in his acceptance of reality

as socially created and devoted his book How Real is Real?. (58) to that theme. He is seemingly unaware that he is mixing

incompatible epistemologies. The Theory of Logical Types was based on the belief that communication must provide clear

accounts for an external, untangled reality. Watzlawick (58), however, posits emergent social realities created by

communication itself.

Definition 1: Hierarchical Relationships: Two units of meanings are in a hierarchical relationship when one unit

forms the context for interpreting the meaning and function of the other.

In adults, for example, the sarcastic tone

(paralinguistic features) of a message usually forms the context for interpreting the verbal content. The concept of

hierarchical relationships is distinctly non-Aristotelian. A context is not simply a natural grouping of units in a class as in an

Aristotelian genus-species relationship. The hierarchical concept breaks with Aristotle's principle that an entity must be

"either A or not A." In a hierarchically organized set of meanings, a message can be A or not A depending upon the context

in which it appears. Thus, in one context a "nip" counts as an effort to harm and invokes retaliation. But in the context

"play" the nips exchanged by the monkey Bateson observed did not carry the meaning of threat and did not invite efforts to

cause harm.

Definition 2: Reflexive Loops: Reflexivity exists whenever two elements in a hierarchy are so organized that each is

simultaneously the context for and within the context of the other. We can identify a reflexive loop in a system when by

moving up or down in a hierarchical system we find ouselves back where we started. As discussed earlier, such loops may

be produced by a simple one-step reflexive relationship (i.e., when a statement forms its own context) or may involve two

or even more steps (e.g., A is the context for B, which is the context for C, which is the context for A.)

The following set of propositions summarizes current research. The propositions themselves should be understood

within the context provided by the postulate and definitions above.

Proposition 1: Some degree of reflexivity is common in hierarchical relationships. Research in the constructivist

tradition (32) supports the claim that there is reciprocal influence between units at two levels of hierarchical organization

even when there is no doubt which particular level is higher than the other. Two similar studies of attribution by Peabody

(42) and Delia (18) illustrate this point. Both researchers had subjects evaluate a set of traits in a list. The researchers then

selected a particular subset of traits designed to generate a higher level global impression. Peabody found that a set of

all-positive traits could be selected that would create a negative global impression. Delia showed that once a global

impression is formed, subjects would reevaluate the valence of the particular traits that make it up. Delia also found that the

valence of the higher level impression could not be explained by any linear aggregate combination of trait valences. The

work of Delia and Peabody studied changes in preexisting hierarchical relationships. Hinkle (27) found that a change in a

higher order concept has substantial impact on subordinate units of meaning. For example, suppose a conversation between

husband and wife is perceived by one partner as an episode of "helpful advising." In that context the message "you must

doto succeed" might well count as "help and support" and carry a positive valence for the hearer. But now suppose that

the hearer thinks of the episodic context as "dominating." The same message and tone could now count as the negatively

valenced act of "ordering me around" or "disrespect for my abilities." While change at the higher level brings dramatic

changes in meanings, Hinkle also found that contextual units are not (nor should they be) immune from all changes in

lower-level units of meanings. To continue our example, suppose that the married couple's usual pattern of exchanging

"helpful advice" contains in this particular enactment a few more messages that in other contexts could be disagreeable

orders. Chances are these messages too will be counted as help or support. Now suppose that one partner uses a high

number of these messages and adds, "If you don't do it my way, you're just stupid." The spouse might take the last message

as a "joke" because "insults" do not fit in their episode of "helpful advising." But, more likely, the set of messages now looks

so unlike an episode of "helpful advising" that a new context is assumed and messages, including prior messages, are

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

4

assigned meaning in new ways. Without that implicative force from parts up to whole, shifts in context could not be

perceived, and new patterns of talk could not be established and subsequently recognized. Rommetveit et al. (49) describe

social action as a process of tacking back-and-forth between higher and lower levels of meaning. The research of

Rommetveit et al. (49) and the work previously cited lead to the conclusion that the relationship between meanings at two

levels of hierarchical organization involves a weaker forcethe upward implicative forceby which particulars imply

meaning at a higher level of abstraction, and a stronger forcethe downward contextual forceby which a higher level of

meaning defines meaning at the lower level.

When the implicative and contextual forces are equal, a reflexive loop is formed. To illustrate, let us once more extend

our example. Suppose one conversant receives the message, "If you don't do it my way you're just stupid," in the context of

what he or she thought to be an episode of "helpful advising." The conversant sees no place for such a message in an

episode of advising and feels very strongly that the whole pattern of talk must be redefined as "domination and resistance."

Our hypothetical conversant feels just as strongly, however, that the episode must really be the spouse's effort to advise and

support and in that context the message should be taken as "help" not "insult." Thus, the message is the context for the

pattern, and the pattern is just as certainly the context for the message. If the forgoing analysis is correct, then surely it is not

useful to conceive of meanings neatly arranged in classes as the prototype of sound communication. This analysis also

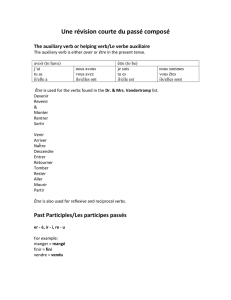

opens the way for measuring degrees of implicative and contextual force. Such measurement could be based on the

algebraic models shown in Figure 2 depicting three kinds of relationships that can exist between levels of meaning in a

hierarchical system. It should also be apparent that the absence of implicative force is problematic. Contexts that cannot

change in response to any changes at a lower level could be symptomatic of an unhealthy system incapable of renegotiation

or growth.

Figure 2.

Algebraic expressions of the three kinds of relationships that can exist between two levels of meaning in a

hierarchical system

Temporality corollary 1.1: There is a temporal dimension to the experience of reflexive relationships. Rommetveit's

(49) work supports the idea that persons monitor the relationships between higher-and lower-order meanings over the

temporal course of conversation. Monitoring allows them to perceive shifts in context and problems in the goodness of fit

between the context assumed to be in force and lower-order meanings. Reardon (47) has proposed a Deviation Tolerance

Model that posits a temporal monitoring process in the form of an elaborated-cognitive plan. Reardon's work provides an

account of how Rommetveit's tacking back and forth may operate.

A temporal dimension is also present when a fully reflexive loop is formed. In a fully reflexive system a person first

examines one aspect of the loop and draws an interpretation "If this is helpful advising, that message must be a joke."

The other side of the loop is then examined "But if this message is an insult, then we are in an episode of "domination."

Thus a fully reflexive loop involves an experience defined in part by timea person experiences each side of the loop as

context for the other during a constricted period of time while attempting to interpret a particular unit of social meaning.

Logicians Brown (12) and Varela (55) both claim that reflexive relationships must be understood as movements through

time.

Whole-part corollary 1.2: Hierarchical relationships are not always isomorphic with part-whole relationships. In our

discussion of Proposition 1, we observed that a particular message may emerge as the context through which a whole

pattern of interaction takes on new meaning. To illustrate our point, consider this: One's self-concept evolves through

participation in many relationships, and each relationship is made up of various episodes of interaction. Studies of aging

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

5

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

1

/

20

100%