A THEORY OF COMPLEXES*

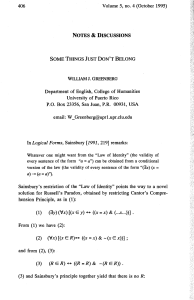

William J. Greenberg

It is vain to do with more It is vain to try to do with

what can be done with fewer. fewer what requires more.

Entities must not be mul- Entities must not be reduced

tiplied beyond necessity. to the point of inadequacy.

--William of Occam --Karl Menger

*Epistemologia XIX, 1996, pp. 85-112

Abstract:

In 'A Theory of Complexes', the simple form of the pure theory of identity found in

logic books is subordinated to a complex form of the theory whose background

ontology is one of structured individuals, orcomplexes. In the complex form:

The axioms of the simple form proceed from principles more basic.1

The semantic difference between (true) 'a = b' and 'a = a' supervenes on features

of a and b.2

Identicals such as nine and the number of planets differ in their modal

properties and relations.3

'A Theory of Complexes' puts into question: the privileging of FOL individuals, the

expressive completeness of FOL, and ontology-free logic.

3

1.1 Introduction

1

In his review of Errol Harris's An Interpretation of the

Logic of Hegel,

2

John E. Smith highlights what is mainly at issue

between the Hegelian conception of logic and the formalist

conception favored by modern empiricism and many forms of analy-

tic philosophy. The Hegelian holds logic to be "internally

related at every level to the real content it articulates" (463).

In contrast, the formalist pegs logic as neutral--both with

respect to "the nature of things" and to "what there is" (ibid.).

How fares the logic of identity in this dispute? Is iden-

tity neutral, both to "the nature of things" and to "what there

is"? Or is the complexity of this relation a legacy of its terms?

From a formalist standpoint, the identity-relation is indif-

ferent to the nature of its terms: what a particular is (qua

value of a variable) has no bearing on its relation to itself.

Unrelated to the things it relates, identity thus has its nature

imposed from without--by classical axioms which appear in the

1

I am grateful to Paul Schachter, John Olney, and an anonymous referee for

comments on earlier versions of this paper--and to the College of Humanities of the

University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras for reductions in load which helped make

completion of this paper possible.

2

British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, V. 36, No. 4, Dec. 1985:

459-465.

4

guise of empirical observations or arbitrary stipulations, or as

the inexpugnable avatars of a Self-Certifying Logical Truth.

In contrast, from the (broadly) Hegelian standpoint of 'A

Theory of Complexes', the properties of identity have their

source in the kind of entity over which individual variables

range: a particular--the particular-cum-complex--which, unlike

the denatured simple of Russell, Bergmann, Allaire, et al.,

3

is

ontologically differentiated and logically complex. The intrin-

sic features of this particular ground a minimal identity rela-

tion

4

, which ramifies classically and non-classically.

5

These

3

Such a particular is as portrayed by John Baker, in 'Particulars: Bare,

Naked, and Nude,' (Nous, V. 1, No. 2, May 1967: 211-212):

Particulars are nude in that they have no natures, that is, they are not

necessarily connected to any specific property or set of properties. A

nude particular has no nature, and is to be distinguished from the naked

particular which has no properties. Those who claim that there are bare

particulars, Russell, Bergmann, Allaire, et al., claim that they are nude

of natures... (211)

4

By a minimal identity-relation I understand one whose properties--symme-

try, transitivity, weak reflexivity, indiscernibility for identicals and

identity for self-idenical indiscernibles--are criterial for identity.

5

The classical relation being strongly reflexive, indiscernibles are

identical. In contrast, in the non-classical relation identity is partially

irreflexive, and so some indiscernibles are not identical.

5

features also ground a difference between formal and material

identity--the identity of a and a and the identity of a and b--

which sets 'a = a' and 'a = b' apart in cognitive content. Such

properties of identity are thus not external to its terms, as in

formalist treatments. Here they are engendered instead by fea-

tures of the entity which identity self-relates.

A theory of the particular-cum-complex encapsulates a theory

of its constituents: haecceities

6

and individuals

7

. To the theory

HI of haecceities and individuals I now turn.

1.2.0 The Language of HI

HI is developed within a first-order, multi-sorted language

L. Among its primitive signs, L counts two predicate constants,

(1.1)"ex" for exemplification

(1.2)"=" for identity

three sorts of variables,

(2.1)variables for individuals: u, v, w, x, y, z, u1, u2, ...,

ui, ...

6

Pick any particular. Corresponding to your particular is a property

that, as established by T46 (see section 1.4.6.1), only your particular has if

anything does. This property is a haecceity. My notion of a haecceity and

Adams's (1979, 1981) notion of a thisness are compared in note 24.

7

A haecceity needs a support, or substratum, if it is to belong to an

actual thing. An entity which can be such a support, or substratum, is an

individual.

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

38

38

39

39

40

40

41

41

42

42

1

/

42

100%