COLLOCATION, COLLIGATION AND

ENCODING DICTIONARIES. PART I:

LEXICOLOGICAL ASPECTS

Dirk Siepmann: Universita« t-GH Siegen, Fachbereich 3, Adolf-Reichwein-Strae,

D-57068 Siegen,Germany (dsiepmann@t-online.de)

Abstrac t

This article attempts to synthesise recent advances in collocational theory into a

coherent framework for lexicological theory and lexicographic practice. By posing a

number of fundamental questions related to the definition of collocation, it critically

reviews frequency-based, semantic and pragmatic approaches to collocation. It is found,

among other things, that two types of collocation, namely ‘long-distance’ collocation

and collocation between semantic features, have suffered almost total neglect. This leads

to suggestions for a new division of the collocational spectrum and for a revised

definition of ‘collocation’ based on the notions of ‘usage norm’ (Steyer 2000) and

‘holisticity’ (Siepmann 2003). It is argued that this new view of collocation considerably

widens the dictionary maker’s brief, since future lexicography will have to provide a full

account of both structurally simple and structurally complex units, including fixed

expressions of regular syntactic-semantic composition (see Part II of this article, to be

published in the March issue of this journal).

1. I n tr o du c t io n

According to modern science, there is no such thing as ‘independent existence’;

at least since the advent of chaos theory, there has been full recognition that

all forms of life and material phenomena, whether at the micro-level or at the

macro-level, are interdependent. In linguistics, this realization has found its

fittest expression in the idea of linguistic rather than literary ‘intertextuality’,

whereby the meaning of one text and its constituent elements depends on

millions of other texts using similar or identical elements. Textual meaning is

thus created by the interplay of two types of repetition, viz. (a) collocation

(in the largest possible sense, including colligation

1

and phraseology) and

(b) cohesion. It turns out that one instance of collocation and the entire

language are mutually illuminating, since the instance is understood in terms of

International Journal of Lexicography, Vol. 18 No. 4

ß2005 Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For permissions,

please email: [email protected]

doi:10.1093/ijl/eci042

the whole, and the whole in terms of the instance (cf. Hunston 2001: 31); taking

this a bit further, we might say that not only is each pattern necessary for

comprehending the sum total of similar patterns, but each pattern is

also a miniature version of that sum total, as shown by the fact that the

meaning of individual patterns (e.g. German ‘sonniges Gemu

¨t’ [‘sunny

disposition’ ¼irrepressible high spirits] vs ‘sonnige Lage’ [sunny location]),

even if shorn of any context, is evident to the native speaker.

This relatively recent view of meaning creation (Hoey 1991, 1998, 2000,

Feilke 1994, 1996) seems much more in keeping with speakers’ intuitive

knowledge about language than was the case in earlier structuralist theories.

The latter tended to assume that expressions such as ‘sonnige Lage’ have

both a compositional, literal meaning and a non-compositional, figurative

meaning (Feilke 1996: 128). In an intertextual or socially-based view of

meaning creation, the compositional meaning is exposed for what it is, namely

an abstraction of the linguist which has no base in the native speaker’s

mental lexicon; the expression ‘sonnige Lage’ is then considered to be a

‘holistic’ sign that is irreducible to the sum of its parts. In a related

development, computational and cognitive linguists have used corpus-linguistic

insights to work out models of language grounded in actual usage rather

than abstract general rules (Chandler 1993, Croft and Cruse 2003, Skousen

1989). In these models word or clause formation is by analogy with existing

exemplars, and it will be seen that such models can also be applied to

collocation.

This article reviews, one by one, the various defining criteria that have in

the last half century been called upon to define the notion of collocation,

pursuing a dual objective: (a) to show that none of these criteria apply in

all cases, so that we can at best give a prototypical definition of collocation,

and (b) to demonstrate that the problems associated with the definition

of collocation stem from the mechanistic, old-paradigm view of language

embodied in structuralist theories which try to impose theoretical abstractions

on an infinitely complex reality arising from communicative interaction and

the institutional practices such interaction puts in place. This will then allow

us to provide a more secure and more broadly based underpinning for the

treatment of colligation and collocation in lexicography. With the exception

of Steyer (2000), no such model has as yet been proposed.

The subject of collocation has been approached from two main angles:

on one side are the semantically-based approaches (e.g. Benson 1986, Mel’c

ˇuk

1998, Gonza

´lez-Rey 2002, Hausmann 2003, Grossmann and Tutin 2003) which

assume a particular meaning relationship between the constituents of a

collocation; on the other is the frequency-oriented approach (e.g. Jones and

Sinclair 1974, Sinclair 1991, Sinclair 2004, Kjellmer 1994) which looks at

statistically significant cooccurrences of two or more words. This theoretical

distinction is paralleled by a geographical divide: the semantic approach has its

410 Dirk Siepmann

origins in continental European research into phraseology, while the frequency

approach is firmly rooted in British contextualism. There has until now been

surprisingly little exchange between the two groups, and when the semanticist

Hausmann (2003) claims to have won the war over collocation, one wonders if

that war has ever been fought.

A third, more recent approach to phrasemes and collocations (Feilke 1996,

2003) might be termed ‘pragmatic’, since it claims that the structural

irregularities and non-compositionality underlying such expressions are

diachronically and functionally subordinate to pragmatic regularities deter-

mining the relationship between the situational context and linguistic forms.

In this view, collocation can best be explained via recourse to contextualisation

theory (Fillmore 1976).

In what follows, I shall argue that there is no reason to resort to the military

metaphor, let alone go to war on matters of collocation. It is much wiser to

unify the three approaches. Tersely stated, I shall argue the following theses:

(1) Only the frequency-based approach can provide a heuristic for discovering

the entire class of co-occurrences; in a way, it is safe from refutation, but

empty – it gives us all the raw material, but tells us nothing about how this

material came to be or how it is to be structured; it has also resulted in

lexicographic products of doubtful value, such as Kjellmer (1994) and

Sinclair (1995) (cf. Hausmann 2003: 319–320, Siepmann 1998).

(2) By contrast, the semantically-based approach is fragmentary – it cannot

account for all possible cases. It would nevertheless seem absurd to

abandon such an intuitively appealing approach at the first appearance of a

counterexample, since it has given rise to reliable collocational dictionaries

such as Langenscheidts Kontextwo

¨rterbuch Franzo

¨sisch-Deutsch.

(3) Likewise, as I shall explain below, a purely pragmatic approach relying on

the extralinguistic context cannot explain a large number of co-occurrences

operating at the level of semantic features.

(4) It follows from this that the debate between the various approaches is a

more/less rather than a yes/no issue. What is needed is an extension of the

semantically-based approach that will take account of strings of regular

syntactic composition which form a sense unit with a relatively stable

meaning. ‘Lexical bundles’ (Biber et al. 1999) such as je sais que c’est or it’s

been will not be included among the class of collocations (cf. Siepmann

2003). Although such sequences may perform similar or identical functions

across a range of texts, they have no meaning ‘by themselves’. In sharp

contrast, there are good theoretical and practical reasons for subsuming

under the notion of collocation such colligational patterns as regarde ou

`tu

vas, dans les colonnes de (þname of newspaper or magazine) or si elle est

prise a

`temps (referring to an illness), which have so far been regarded as

free sequences of words subject only to general rules of syntax and semantics.

Collocation, Colligation and Encoding Dictionaries 411

For greater expository convenience, the various questions raised by the

discussion of the above theses will be broken down under five separate heads:

(1) How many elements make a collocation?

(2) What elements make a collocation?

(3) Are collocations arbitrary?

(4) Can we distinguish between collocations and phraseology on the one hand,

and collocations and free combinations on the other?

(5) Are collocations monosemous and monoreferential? Are there synonymic

collocations?

This will lead to a division of the collocational spectrum into four major

categories, all of which have their role to play in the making of dictionaries,

especially those aimed at the non-native speaker.

My theoretical arguments will be leavened with a large number of concrete

examples encountered during the ongoing compilation of three unabridged

bilingual thesauri intended mainly for non-native speakers of English, French

and German (the ‘Bilexicon’ project). All of these examples have been drawn

from the following authentic sources (for a detailed account of corpus

construction, see Siepmann 2005):

(a) electronic editions of wide-circulation quality newspapers and news

magazines (The Times, The Guardian, The Economist, Le Monde,

Le Monde Diplomatique, Su

¨ddeutsche Zeitung, Frankfurter Rundschau,

Der Spiegel );

(b) a large corpus of academic texts produced from reviews, journal articles,

doctoral theses and portions of books;

(c) 50-million-word corpora of fiction and fan fiction freely available on

the Internet;

(d) a 100-million word corpus of the language of motoring based mainly on

Internet sources.

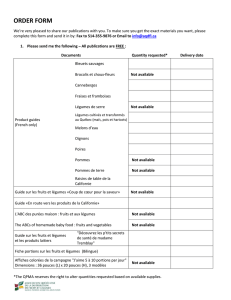

Table 1 gives a breakdown of the sources used by corpus type, content, size,

baseline year and analysis software.

2. How many elements make a collocation?

It is accepted wisdom among European researchers that collocations are

binary units, and this is probably true for the majority of the class. Thus, the

most common type of collocation is the combination of a noun with a verb,

and there are hundreds of thousands of examples which confirm this point

of view (e.g. take a step,launch an appeal ). Mel’c

ˇuk (most recently 2003)

argues that the constituents of such collocations tend to be linked by a

standard lexical function, such as Magn (rely on [Magn] ¼heavily, beautiful

412 Dirk Siepmann

Table 1: Corpora used in this study

Corpus (Abbreviation) Type Content Word Count Baseline Year

Corpus of Academic

English (CAE)

full-text reviews, journal articles, doctoral

theses and portions of books

30 million 1980 (less than 5% of texts

predate 1980)

Corpus of Academic

French (CAF)

full-text reviews, journal articles, doctoral

theses and portions of books

30 million 1980 (less than 5% of texts

predate 1980)

Corpus of Academic

German (CAG)

full-text reviews, journal articles, doctoral

theses and portions of books

30 million 1980 (less than 5% of texts

predate 1980)

Corpus of English

Fiction (FE)

full-text and samples reviews, journal articles and

portions of books from CAE

50 million 1980

Corpus of French

Fiction (FF)

full-text and samples reviews, journal articles and

portions of books from CAF

50 million 1980

Corpus of German

Fiction (FG)

full-text and samples reviews, journal articles and

portions of books from CAG

50 million 1980

Corpus of English

Motoring (CME)

full-text and samples Internet forums and chatrooms,

electronic magazines, transport

sites, encyclopaedia and

dictionary articles

100 million 1995

British Newspapers and

News Magazines (NE)

full-text Issues of The Times, The

Guardian and The Economist,

published in London

100 million 1990

(Continued)

Collocation, Colligation and Encoding Dictionaries 413

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

1

/

35

100%