Chapter 9 – Sallustius: Mind, Body, & Glory — Latinitium

CHAPTER 9 – SALLUSTIUS: MIND,

BODY, & GLORY

2000 YEARS OF LATIN PROSE

A 21st Century Anthology of Latin Prose

A LATIN ANTHOLOGY FOR THE 21ST

CENTURY

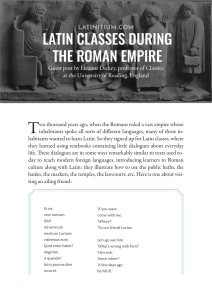

Two thousand years of Latin Prose is a digital anthology of

Latin Prose. Here you will be able to find texts from two

millennia of gems in Latin. In this nineth chapter, we will

learn more about Sallustius, known to many as Sallust. We will

also read a passage from his most famous work Bellum Catilinae.

If you want to learn more about the anthology, you will find the

preface here.

CHAPTER 9: SALLUSTIUS

CONTENTS

1.

The Life and Works of Sallustius

2.

Audio & Video

3. Latin Text

4. Keywords & Commentary

5. English Translation

Chapter 9 – Sallustius: Mind, Body, & Glory — Latinitium

❶

LIFE AND WORKS

In this section you will learn about the life and works of

Sallustius.

SALLUSTIUS

(86-35 B.C)

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, or simply Sallust, was a Roman

politician and historian, probably born in Amiternum in

central Italy.

LIFE OF SALLUSTIUS

Of Sallustius' early years we know very little, hardly anything.

It is not until the 50s B.C. that we have more than speculation

to go on.

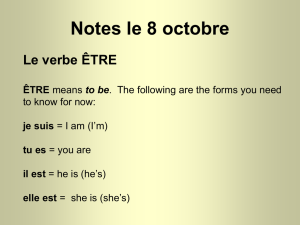

PORTAIT OF SALLUSTIUS BY LOUIS-GABRIEL

MONNIER, 1777

Chapter 9 – Sallustius: Mind, Body, & Glory — Latinitium

Prior to 52 B.C. Sallustius might have been a quaestor, though

this has been disputed. In 52 B.C. he became a Tribune of the

Plebs. However, two years later in 50 B.C. he was, along with

some others, driven from the senate. This was perhaps (but

nothing is certain) due to his sympathies towards Julius Caesar,

a man he would support and later thank for his life.

Caesar later appointed Sallustius commander of a legion. Even

though he did not stand out militarywise, he was rewarded for

his support and loyalty by being appointed governor of the

province Africa Nova (the old Kingdoms of Numidia and

Mauretania in northwestern Africa).

Sallustius was not a good governor. If we are to believe historian

Dio Cassius (155-235 A.D.), he was a terrible, oppressive

governor. According to Cassius (lib 43.9), he harassed and

plundered his subjects, confiscated property and took bribes to

line his own pockets. When he returned to Rome, sometime

around 45 or 44 B.C., it was only thanks to Julius Caesar that he

escaped charges.

Sallustius turned away from public life, perhaps after Caesar's

death, though the exact time for his withdrawal is uncertain. He

then spent the rest of his days writing historical literature and

developing his gardens, the Horti Sallustiani.

LIEBIG CARD SET: "GRANDS HISTORIENS ET EPISODES DE LEUR VIE", CA 1900

Sallustius life was a little bit of a contradiction:

On the one hand, we have an active politician whose writings,

that we soon shall turn to, are (amongst other things) famous

for their stern critique of the loose morality of the Roman

aristocracy, and for their concern about Rome's moral

Chapter 9 – Sallustius: Mind, Body, & Glory — Latinitium

.

decline.

On the other hand, we have a man who oppressed the region he

was supposed to govern and was infamous for his loose living.

As an example: Aulus Gellius relates a story from Varro about

the time when Sallustius was caught, red-handed, by Titus

Annius Milo (known from Cicero's speech Pro Milone)

committing adultery. Rumour has it that the woman Sallustius

was sleeping with was none other than Milo's own wife Fausta

Cornelia, daughter of Sulla. Gellius does not point her out;

however, Milo's reaction to Sallustius' indiscretion speaks for

itself: he beat the author with thongs and refused to let him

leave until Sallustius had paid him a sum of money.

"in adulterio deprehensum ab Annio Milone

loris bene caesum dicit et, cum dedisset

pecuniam, dimissum. "

– Aulus Gellis, lib. XVII.xviii

Dio Cassius, though not a contemporary, harshly remarks that

Sallustius did not practice what he preached. (Dio Cass. 43. 9)

WORKS OF SALLUSTIUS

Three of Sallustius' works remain today; Fragments of

the Historiae, Bellum Iugurthinum, and Bellum Catilinae.

The Historiae was a continuation of Cornelius Sisenna's (120-67

B.C.) now lost work, also called Historiae. Sisenna's work was a

history covering the years 90 B.C. to 78 B.C.

Sallustius' Historiae began where Sisenna's work ended, 78 B.C.

and continued to the year 67 B.C. It would have continued

onwards, but Sallustius died before he could finish it.

Today we have parts left from the Historiae; four speeches, two

letters and about 500 fragments.

Bellum Iuguthinum was written around 40 B.C. and deals with

the Jugurthine War (111-105 B.C.) fought between Jugurtha, king

of Numidia and Rome.

Chapter 9 – Sallustius: Mind, Body, & Glory — Latinitium

Bellum Catilinae is the most famous of Sallustius' works and

was perhaps written around 42 B.C. as his first

published work. It is also to this work we shall turn in today's

chapter to sample his writings.

Bellum Catilinae goes through the Catiline Conspiracy of 63 B.C.

that we have already heard a little bit about in this digital

Anthology's Chapter 5: Cicero and his De Catilina.

The conspiracy was that of a plot to

overthrow the Roman Republic and

has been named after the main

conspirator, Lucius Sergius Catilina.

Though the conspiracy happened

during SallustiusÕ life, it is most

likely that he was not in Rome at the

time, but instead was in the service

of the military. His Bellum Catilina is

THE BEGINNING OF SALLUST’S

BELLUM IUGURTHINUM, IN MS.

BIBLIOTECA APOSTOLICA

VATICANA, VATICANUS PALATINUS

LAT. 883, FOL. 21R., 12TH CENTURY.

DE CONJURATIONE CATILINAE,

MANUSCRIPT FROM 1475 not written around the time of the

conspiracy in the 60's B.C. but between 44 and 40 B.C. Thus,

ca. 20 years had passed in between the actual events and the

book.

The passage we shall be looking at today is the beginning

of Bellum Catilina. Sallustius is not one to go straight to the

point, but instead sets the tone of his work with this passage

with thoughts on the mind, body, and glory.

written by Amelie Rosengren, M.A.

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

1

/

16

100%