, Vol. , No. , .

© Donald Critchlow and Cambridge University Press

doi:./S

e . a ttila a ytekin

Tax Revolts During the Tanzimat Period

(–) and Before the Young Turk

Revolution (–): Popular Protest and

State Formation in the Late Ottoman Empire

e Ottoman Empire underwent a slow but decisive transformation from the

early eighteenth century onward. e societal change observed during the

eighteenth century was accompanied by change in state structures during

the reign of Selim III (–) and Mahmud II (–). e most com-

prehensive transformation of the Ottoman polity, however, took place during

the so-called Tanzimat period (–). While the subsequent long reign of

Abdulhamid II (–) put a halt to some of the trends for reform, the

society and the state continued to evolve. e Hamidian period came to an

end with the Revolution of , which made the empire a constitutional

monarchy.

e question of taxation was one of the issues the policymakers had to

deal with throughout the entire process of transformation. Tax-related

problems became especially pressing during two particular periods, rst a er

the declaration of the Tanzimat edict in , and then during the last years of

Abdulhamid’s reign. State policies regarding taxation and the popular

reaction to them became one of the most important aspects of state formation

during the Tanzimat and pre- periods.

is is not surprising given the signi cance of taxation for modern states.

First, the balance of state nances, therefore many of its capacities, depends

on the state’s ability to tax the population. A large tax base, a sound taxation

Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030613000134

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Fribourg ARCHIVE use - do not de-dupe, on 28 Jan 2019 at 15:12:50, subject to the

e . a ttila a ytekin |

system, and of course a quiescent population are therefore critical for any

modern state to function properly. Second, the ability to tax also re ects a

state’s legitimacy in the eyes of the people. Coercion might not be su cient in

itself for taxation if the state does not enjoy a certain amount of legitimacy at

the societal level. ird, taxation is a class issue. Who is taxed how much and

who enjoys the bene ts of the tax collected are questions that speak not only

to state structure, but also to the relations between upper classes and lower

classes. e latter o en have a sharp sense of what is fair and what is not, and

that does in uence their attitudes toward state attempts at taxation.

is article is roughly divided into two sections. In the rst section,

I focus on the tax revolts that took place during the Tanzimat period; the

second section is about the tax revolts that preceded the Revolution of .

In both sections, I describe the general characteristics of the period and the

most signi cant revolts and discuss the rebels and their demands. I also

analyze the Ottoman state’s responses to the two waves of revolt. e rst

section also includes a theoretical discussion about the state-formation

approach. e Tanzimat period and pre- revolts are comparatively

discussed in the Conclusion.

t ax r evolts in the

t anzimat

p eriod: t hree p erspectives on

l ate o ttoman h istory

e Tanzimat is the name historians give to the period that began with the

declaration of the Imperial Rescript of Gülhane on November , , and

ended with the promulgation of the rst Ottoman constitution in . e

reform program initiated and implemented by the Ottoman state in this

period is also known as the Tanzimat .

e Gülhane Rescript had a quite conventional preamble that attributed

the recent problems of the Ottoman polity to deviation from sacred law.

However, despite the traditional beginning and wording, the document was

indeed a radically original one, which set forth guarantees ensuring Ottoman

subjects security of life, honor, and property; called for a regular system of

taxation and speci cally the abolition of the tax-farming system; a regular

system for military service that would include non-Muslim subjects of the

empire; and equality between Muslim and non-Muslims.

e rescript turned out to be the beginning of a great series of reform. In

the subsequent decades, a new, modern bureaucracy replaced the old one

and the number of state servants increased dramatically. Decision-making

processes were gradually democratized; a number of quasi-legislative councils

Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030613000134

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Fribourg ARCHIVE use - do not de-dupe, on 28 Jan 2019 at 15:12:50, subject to the

| Tax Revolts During the

Tanzimat

Period

with real powers were constituted at the center as well as in the provinces. e

principle of equality before law was recognized, along with a new notion of

citizenship. ere was a massive codi cation campaign in which either original

laws were enacted or foreign laws were adapted in the elds of civil law, penal

law, commercial law, procedural law, and citizenship law. A gradual but

decisive process of secularization began, seen most clearly in the religious

courts’ loss of jurisdiction to secular ones. As we shall see, not all of these

steps taken as part of the Tanzimat reform program were successful; yet the

Tanzimat as a whole irreversibly changed the nature of Ottoman polity. It was

in fact the most comprehensive attempt at modern state formation in the

Ottoman Empire to date. Scholarship, therefore, has shown a high interest in

the period. In contrast, despite such interest, the Tanzimat reform program in

particular and the late Ottoman reforms in general have not been adequately

analyzed.

is is partly related to the in uence of modernization theory, which

has, until recently, dominated the eld of Ottoman studies. e proponents

of this theory have seen in the emergence of modern Turkey a success story.

All the changes that took place in di erent spheres of life in the period,

from the late eighteenth to early twentieth centuries, have been reduced to

“modernization,” according to which a couple of reformist sultans and a

handful of Western-minded bureaucrats tried to save the empire from collapse

by emulating the successful European model and restructuring its state along

those lines. In this story, the history of the Ottoman Empire from the late

eighteenth century onward becomes one of struggle between modernizers

and forces of reaction.

1 Dependency theory has been developed as an alterna-

tive to the modernization approach. An o shoot of dependency theory,

the world-system perspective, produced by Immanuel Wallerstein and his

colleagues at SUNY Binghamton from s, has had a short-lived, yet

important, impact on Ottoman studies.

2 With their stress on economic relations,

world-system scholars have shown that the late Ottoman Empire cannot be

understood solely in terms of political modernization. eir works that focus

on the incorporation of the Ottoman lands into world capitalism have pointed

out those aspects of the transformation of Ottoman polity that had hitherto

been in the dark. In contrast, using world-system theory to analyze late

Ottoman history has its problems, some of which are related to its basic

concepts. e concepts of “incorporation” of the Ottoman Empire into the

world capitalist system, or, even more so, the “penetration” of capitalism into

the Ottoman territories, suggest that the process was essentially external to the

Ottoman social formation. us, the contribution of the studies in uenced

Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030613000134

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Fribourg ARCHIVE use - do not de-dupe, on 28 Jan 2019 at 15:12:50, subject to the

e . a ttila a ytekin |

by the world-system approach to Ottoman studies has been overshadowed by

the implicit assumption on which they are based: the internal dynamics of the

empire was not strong enough to create a profound change by themselves.

Although the world-system approach by and large lost its appeal among

Ottomanist historians, terms such as “incorporation” became staples especially

in the analyses of the nineteenth-century Ottoman economy.

In contrast to the world-system approach that made a strong entrance to

the eld yet le the scene largely unnoticed,

3 the modernization approach

has been subject to sustained criticism. As a result, the more open forms of

the modernization approach have been largely abandoned in the last two

decades. Many of its less-explicit assumptions, however, continue to exert

their in uence on the study of the Tanzimat period. e Tanzimat is still

seen as just another step in a series of reform attempts that stretched from

(the accession of Selim III) to (the establishment of Republic of

Turkey). Moreover, it is still common to consider the Tanzimat reform pro-

gram as a state initiative formulated and implemented top-down by state

o cials.

4 In a similar vein, the social unrest that followed the declaration of

reforms is seen as mere reactions to it.

5 Balkan nationalist historiographies,

by contrast, have tended to see the post- Tanzimat uprisings in the Balkans as

part of, or prelude to, the “national awakening” led by nationally-conscious

urban intellectuals and middle classes. Both approaches have relegated

cultivators to being passive recipients of (national or central) state-building

projects of the elite.

e modernization approach, therefore, has refused to look into the

social dynamics of late Ottoman reform. e world-system perspective, on

the other hand, has conducted the analysis at too high a level of abstraction

and failed to address the internal dynamics of development. In this article,

I discuss the outlines of an alternative approach to late Ottoman history,

derived from the state-formation approach developed by sociologist Derek

Sayer (with his colleague Philip Corrigan and also Harvey Ramsay) based on

a close reading of the works of Marx and Engels as well Weber and Durkheim.

eir approach is particularly suitable for the empirical study of historical

phenomena as it assumes that concepts are empirically open-ended and

necessarily historical. is means that to de ne a social phenomenon, in the

nal analysis, is to write its history.

6 ere is no ground for excluding any

kind of social relation from being a relation of production, or for assigning,

a priori , some social relations to “base” and others to “superstructure.”

7

According to Sayer, the question of what is a relation of production could

only be resolved for particular historical forms using empirical criteria.

Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030613000134

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Fribourg ARCHIVE use - do not de-dupe, on 28 Jan 2019 at 15:12:50, subject to the

| Tax Revolts During the

Tanzimat

Period

eir approach contravenes both the liberal notion of state, which views

it structurally separate from the (civil) society, and the Marxian views that see

the state either as an instrument in the hands of the ruling class or super-

structural. e state-formation approach stipulates that the state, instead, is

necessarily and internally related to capitalist economy. Although state forms

appear separate from the economy and above the society, the former appear-

ance is a result of the fetishized nature of social relations under capitalism,

and the latter is related to the organizing role of the state under the capitalist

mode of production: “ e State within capitalist production, regulates and

orchestrates—in short, organizes— in such a way that the de ning material

characteristics of capitalist production relations (individualization, formal

equality, and a host of social forms) are made to appear the only way those

social activities could be conducted and arranged.”

8 In fact, the state could

organize only by appearing outside economy and above sectional interests in

society.

In their major historical study, e Great Arch , Corrigan and Sayer apply

this perspective, which sees the state not as a thing but as a rei ed, organized,

imposed, and regulated form of social relations of production to English state

formation.

9 ey underline that English state formation did not consist only

of repression. Legal regulation, that is, the law, and moral regulation also

played a signi cant part in the long process of English state formation from

medieval to modern times. Legal and moral regulation reduces all people

to individuals and delegitimizes and even criminalizes alternative forms of

existence. ey create a sense of sameness and commonness while keeping

deep social divisions intact. During state formation, the nation as a politically

de ned entity is also created. On the one hand, nationalism disintegrates

other identities and subjectivities.

10 On the other hand, those who are deemed

worthy to be included in the political nation are included and those who are

considered unworthy or dangerous are excluded or disciplined through

jurisdiction.

11 In the English case, this double process of inclusion-exclusion

was imposed most importantly on the working class and women.

Corrigan and Sayer show that state forms are extremely exible and, as

such, they are constructed through struggle and contention between actors.

One aspect of this contentious process is “the constant ‘rewriting’ of history

to naturalize what has been, in fact, an extremely changeable set of State rela-

tions, to claim that there is, and has always been, one ‘optimal institutional

structure’ which is what ‘any’ civilization needs.”

12 To turn to the Ottoman

case, the preamble of the Tanzimat rescript is quite revealing in this respect.

e authors of the text are at pains to argue that they are o ering nothing new

Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030613000134

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Fribourg ARCHIVE use - do not de-dupe, on 28 Jan 2019 at 15:12:50, subject to the

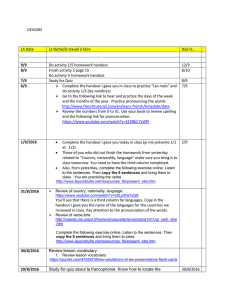

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

1

/

26

100%