Colorectal cancer screening: strategies to select populations with

ABSTRACT

Objective: to analyse the association between rectal bleeding

or a family history of colorectal cancer (CRC) and the results ob-

tained in two rounds of a CRC screening pilot programme per-

formed in L’Hospitalet, Barcelona, Spain.

Subjects: males and females (50-69 years) were the target

population. Together with the invitation letter, they received a

questionnaire in which they were asked about rectal bleeding,

family history of CRC and related neoplasms. The screening test

was a guaiac-based faecal occult blood test (FOBT), and

colonoscopy for positive tests.

Results: 25,829 FOBT were performed in 18,405 individu-

als. Information on rectal bleeding and a family history of CRC

were obtained for 9,849 and 9,865 cases, respectively. Male sex

(OR = 1.32), 60-69 years of age (OR = 1.48), rectal bleeding (OR

= 1.84) and history of CRC (OR = 1.54) were independent pre-

dictors of positive FOBT. With regard to colonoscopy, a greater

risk of diagnosing advanced neoplasm was observed among men

(OR = 2.47) and subjects with a family history of CRC (OR =

1.98).

Conclusions: CRC screening programmes must have instru-

ments that make it possible to select the candidate population and

the possibility of offering a study suited to the risk of individuals

who are not susceptible to population screening by means of

FOBT.

Key words: Colorectal cancer screening. Fecal occult blood test.

Rectal bleeding. Family history of CRC. Risk assessment.

INTRODUCTION

Early diagnosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) remains cru-

cial to the outcome of surgery, which is the cornerstone op-

tion for cure. The incidence and mortality of CRC in the

European Union is considered so disturbing that the Euro-

pean Union Commissioner on Health has recommended

screening programmes with faecal occult blood test

(FOBT) to be considered in all member states (1).

Population screening programmes target individuals

above 50 years old without additional risk factors (symp-

toms suggestive of the existence of CRC, chronic inflam-

matory disease, personal history of adenomas, CRC or

family risk of CRC) (2-4). Clinical guidelines exist for

screening high-risk patients, including those with a histo-

ry of familial polyposis or hereditary non-polyposis col-

orectal cancer (5,6). The possibility of investigating

whether the individuals to be screened have additional

risk factors constitutes an added difficulty in the context

of screening programmes on large populations due to the

significant cost entailed by carrying out exhaustive med-

ical histories in participating subjects who may be sus-

pected to belong to higher-risk groups.

We present the prospective results of the questionnaire

included in the first two rounds performed in a pilot CRC

screening programme based on FOBT performed in

L'Hospitalet, Barcelona. The study endpoint is to evalu-

ate the efficacy of this questionnaire by analysing screen-

ing results and the presence of rectal bleeding or family

Colorectal cancer screening: strategies to select populations with

moderate risk for disease

M. Navarro1,2, G. Binefa1,2, I. Blanco1,2, J. Guardiola3, F. Rodríguez-Moranta3, M. Peris1,2; and the Catalan

Colorectal Cancer Screening Pilot Programme Group*

1Cancer Prevention and Control Unit. Catalan Institute of Oncology. L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona. Spain.

2Bellvitge Institute for Biomedical Research (IDIBELL). L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona. Spain . 3Digestive

Endoscopy Unit. Gastroenterology Department. University Hospital of Bellvitge. Barcelona, Spain

1130-0108/2009/101/12/855-860

REVISTA ESPAÑOLA DE ENFERMEDADES DIGESTIVAS

Copyright © 2009 ARÁN EDICIONES,S. L. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

Vol. 101. N.° 12, pp. 855-860, 2009

Received: 18-05-09.

Accepted: 10-07-09.

Correspondence: Gemma Binefa. Cancer Prevention and Control Unit. Cata-

lan Institute of Oncology. Av. Gran Via de l'Hospitalet, 199-203. 08907 Hos-

pitalet de Llobregat. Barcelona, Spain. e-mail: gbinefa@iconcologia.net

Navarro M, Binefa G, Blanco I, Guardiola J, Rodríguez-Moran-

ta F, Peris M; and the Catalan Colorectal Cancer Screening Pi-

lot Program Group. Colorectal cancer screening: strategies to

select populations with moderate risk for disease. Rev Esp En-

ferm Dig 2009; 101: 855-860.

*The Catalan Colorectal Cancer Pilot Screening Programme Group are: M.

Peris, G. Binefa, M. Navarro, J. A. Espinàs, J. M. Borràs, I. Blanco, A. Clo-

pes, V. Moreno, G. Capellá (Catalan Institute of Oncology). J. M. Miquel,

J. M. Nogueira, G. García Mora, J. Martí-Ragué, X. Sanjuán (University

Hospital of Bellvitge). S. Calero (Catalan Institute of Health, Primary He-

alth Care Division).

08. OR 1601 NAVARRO:Maquetación 1 28/12/09 08:04 Página 855

history of colorectal cancer in the participating popula-

tion in the two rounds performed.

METHODS

The CRC pilot screening programme was directed at

the 50-to-69-year-old population in L’Hospitalet, a city of

239,000 inhabitants in the metropolitan area of Barcelona

(Catalonia), Spain. Demographic data on this population

was gathered from the Primary Healthcare Information

System. A hospital cancer registry covering the city was

linked to exclude subjects with a diagnosis of colorectal

cancer. Two screening rounds were successively per-

formed. The first round involved 11,011 of the 63,880

people invited to participate. The second round involved

14,818 of the 66,534 people invited (7).

The population regarded as subject to screening were

sent a letter inviting them to participate in the pro-

gramme, including information on the prevention of CRC

and a questionnaire in which they were asked about any

episodes of rectal bleeding, previous diagnosis of haem-

orrhoids, adenomas, colorectal cancer or inflammatory

bowel disease, having had a colonoscopy in the previous

5 years, as well as the existence of a family member with

CRC or other neoplasms associated with CRC (endome-

trial and kidney). The questionnaire was sent to the whole

target population in the first round, and to the new sub-

jects invited to take part in the second round. Since in

some cases the participants returned the questionnaire

unanswered, the requested information is not available

for all of them.

All subjects with CRC, adenomas or chronic inflam-

matory bowel disease were definitely excluded from the

screening program. Subjects with a previous colonoscop-

ic examination were considered candidates for screening

after 5 years of colonoscopy.

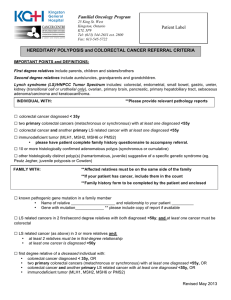

When the questionnaire reported two or more relatives

with cancer, they were phoned through the programme to

check the information and evaluate whether the subject

was eligible for population screening with FOBT or met

the criteria for hereditary colorectal cancer (5,6). If a high

risk family history was confirmed, the subject was ex-

cluded from the programme and was offered to be coun-

selled for a more detailed assessment. The programme al-

lowed the screening of subjects with a family history of

CRC or other non-colonic neoplasms as long as they did

not meet the criteria for hereditary cancer. Rectal bleed-

ing was not considered an exclusion criterion.

The screening test was a guaiac-based faecal occult

blood test every 2 years. Participants were asked to collect

two stool samples from three bowel movements. Dietary

restriction was indicated when a repetition of the test was

necessary. If 5 or 6 samples were positive at initial testing,

or any of the samples under dietary restriction, a

colonoscopy with sedation was indicated. Any polyps

found were removed and biopsies of any masses were ob-

tained. If a patient had more than 1 polyp, the most ad-

vanced pathologic lesion was included in the analysis. The

histological classification of polyps and cancers was based

on World Health Organisation criteria (8). High-risk ade-

noma (HRA) was defined as adenoma with severe dyspla-

sia, adenoma bigger than 10 mm, more than 2 adenomas,

or any adenoma with tubulovillous or villous histology.

Carcinoma in situ was classified as HRA. Low-risk adeno-

ma (LRA) was defined as that of smaller size, tubular type

and low-grade dysplasia. Advanced neoplasms included

invasive cancer or high-risk adenoma.

In the analysis we have taken into account only one

FOBT result for each individual. Hence in participants of

both rounds with a positive FOBT in the second round

we used the results of the questionnaire sent in the first

round.

Differences in categorical variables were compared

with the Chi-square test. In the multivariate analysis, the

association between a positive FOBT or an advanced

neoplasm with the presence of rectal bleeding or a family

history of colorectal cancer was analysed using logistic

regression, adjusting by sex and age. The variables in-

cluded in the multivariate analysis were sex, age and

those with a significant result in the bivariate analysis.

The results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95%

confidence intervals (95%CI). Differences were consid-

ered statistically significant when p < 0.05. All analyses

were performed with the Stata software, version 9.2

(StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS soft-

ware (version 13.0 for Windows).

RESULTS

A total of 1,691 individuals were excluded (986 from

the first round and 705 from the second round), 592

(35.0%) of whom were excluded by means of the assess-

ment of risk factors included in the questionnaires and

considered not eligible for population screening: 262

CRCs, 33 inflammatory bowel diseases, 44 previously

diagnosed colon adenomas, 243 had undergone colono-

scopies in the previous 5 years, and 10 subjects were ex-

cluded due to meeting the criteria for hereditary CRC.

Table I describes the data of participants in both

rounds. A total of 25,829 FOBTs were performed in

18,405 individuals, 7,424 of whom participated in both

rounds. The results of the study have recently been

analysed (7,9). The uptake of colonoscopy among sub-

jects with a positive test was 89% (442/495).

Colonoscopy results were: without findings in 229 sub-

jects, 36 invasive cancers, 121 HRA (33.1% of whom had

an in situ carcinoma), 29 LRA and 27 non-neoplastic

polyps. Of the 18,405 people screened, 14,740 question-

naires were received with some of the requested data.

From these, information was obtained on the presence of

blood in faeces and a family history of CRC in 9,849 and

in 9,865 cases, respectively.

856 M. NAVARRO ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2009; 101 (12): 855-860

08. OR 1601 NAVARRO:Maquetación 1 28/12/09 08:04 Página 856

Table II analyses these two factors in greater detail. It

can be observed that rectal bleeding was more frequent in

participants with a positive result in FOBT (41.8%), in

men (31.7%), in the 50 to 59 age group (30.6%), and in

those presenting haemorrhoids (43.2%). The cases that

most frequently reported the presence of rectal bleeding

were those diagnosed with an invasive cancer (64.3%);

42.9% of individuals without neoplasms (cancer or adeno-

mas) on colonoscopy had haemorrhoids. It can also be ob-

served in table II that the presence of a family history was

more frequent among positive FOBTs (11.0%), in men

(7.6%), and in the 50 to 59-year age group (7.8%). People

with high-risk adenoma detected followed by invasive

cancer were those with the highest frequency of family his-

tories of CRC with 15.9 and 13.9%, respectively.

In the bivariate analysis, the positive result of FOBT

was statistically significant with the variables studied ex-

cept for the presence of haemorrhoids (Table III). Signifi-

cance was maintained in the multivariate model for each

one of the variables, so that a positive FOBT was related

to the male gender (OR = 1.32, 95% CI, 1.08-1.62), be-

longing to the 60 to 69-year age group (OR = 1.48, 95%

CI, 1.21-1.81), the presence of rectal bleeding (OR =

1.84, 95% CI, 1.50-2.26), and having a family history of

CRC (OR = 1.54, 95%CI, 1.11-2.14).

Table IV presents the results of the analysis of the as-

sociation between the diagnosis of advanced neoplasm

and the presence of rectal bleeding or family history of

CRC. In the bivariate analysis, the diagnosis of advanced

neoplasm was significantly associated with the male gen-

der and the presence of a family history. No association

was found with the presence of rectal bleeding or haem-

orrhoids. In the multivariate model, it was observed that

Vol. 101. N.° 12, 2009 COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING: STRATEGIES TO SELECT 857

POPULATIONS WITH MODERATE RISK FOR DISEASE

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2009; 101 (12): 855-860

Table I. Results of the first and second rounds

n %

People screened

18,405

Sex

Female 10,016 54.4

Male 8,389 45.6

Age group (years)

50-59 10,201 55.4

60-69 8,204 44.6

FOBT results

Positive 495 2.7

Negative 17,304 94.0

Not assessable 606 3.3

Colonoscopies

442 89.3

Colonoscopy result

Normal 229 51.8

Invasive cancer 36 8.1

High risk adenoma 121 27.4

Low risk adenoma 29 6.6

Non-neoplastic polyp 27 6.1

Questionnaires

14,740 80.1

Rectal bleeding

No 6,997 47.5

Yes 2,852 19.3

Unanswered 4,891 33.2

Family history of CRC

No 9,134 62.0

Yes 731 4.9

Unanswered 4,875 33.1

Haemorrhoids

No 4,780 32.4

Yes 5,249 35.6

Unanswered 4,711 32.0

Tabla II. Characteristics of people with rectal bleeding or family history of CRC who answered the questionnaire

Rectal bleeding Family history of CRC

No Yes No Yes

n% n%p-value n%n%p-value

FOBT result

Positive 234 58.2 168 41.8 < 0.001 372 89.0 46 11.0 < 0.005

Negative 6,763 71.6 2,684 28.4 8,762 92.7 685 7.3

Sex

Female 3,851 73.5 1,392 26.5 < 0.001 4,863 92.7 381 7.3 0.585

Male 3,146 68.3 1,460 31.7 4,271 92.4 350 7.6

Age group (years)

50-59 3,877 69.4 1,705 30.6 < 0.001 5,152 92.2 440 7.8 0.051

60-69 3,120 73.1 1,147 26.9 3,982 93.2 291 6.8

Screening-detected lesions

Invasive cancer 10 35.7 18 64.3 0.016 31 86.1 5 13.9 0.669

High risk adenoma161 62.9 36 37.1 90 84.1 17 15.9

Low risk adenoma 21 80.8 5 19.2 22 88.0 3 12.0

Non-neoplasic polyp 14 58.3 10 41.7 21 91.3 2 8.7

Without lesions 108 57.1 81 42.9 174 92.1 15 7.9

Haemorrhoids

No 4,058 86.5 631 13.5 < 0.001 4,344 92.6 345 7.4 0.952

Yes 2,923 56.8 2,220 43.2 4,761 92.6 381 7.4

1Carcinomas in situ are included.

08. OR 1601 NAVARRO:Maquetación 1 28/12/09 08:04 Página 857

the risk of presenting an advanced neoplasm was greater

among men (OR = 2.47, 95% CI, 1.59-3.83) and among

people with a family history of CRC (OR = 1.98, 95%

CI, 1.02-3.84).

DISCUSSION

Our findings from the two first rounds of the Colorec-

tal Cancer Screening Programme show the higher risk of

a diagnosis of advanced colorectal neoplasm among male

participants (OR = 2.47, 95% CI, 1.59-3.83) and in those

with a family history of CRC (OR = 1.98, 95% CI, 1.02-

3.84). The results according to age group and presence of

rectal bleeding were not significant.

Currently, there are published guidelines on the differ-

ent strategies of CRC screening according to the risk in

the population (5,10). An annual or biennial FOBT is cur-

rently recommended for people above 50 with average

risk. A meta-analysis has suggested that the magnitude of

the relative reduction in mortality rate by FOBT screen-

ing is 16% overall and 23% after adjustment for screen-

ing attendance (11).

Few data have examined the prevalence of inappropriate

CRC screening (12,13). Fisher et al. (13) investigated a

sample of 500 consecutive patients who had a FOBT. Over-

all, 35% of patients received inappropriate screening, 20%

because of signs or symptoms of gastrointestinal blood loss

or a higher-than-average risk of CRC. If we take into ac-

count the progressive increase in the screening of the low-

858 M. NAVARRO ET AL. REV ESP ENFERM DIG (Madrid)

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2009; 101 (12): 855-860

Table III. Analysis of positive FOBT

Bivariate analysis Multivariate analysis

n (%) OR (95% CI) p-value OR (95% CI) p-value

Sex

Men 272 (54.9) 1.47 (1.22-1.77) < 0.001 1.32 (1.08-1.62) < 0.001

Women 223 (45.1) 11

Age (years)

60-69 243 (49.1) 1.61 (1.35-1.95) < 0.001 1.48 (1.21-1.81) < 0.001

50-59 252 (50.9) 11

Rectal bleeding

Yes 168 (41.8) 1.81 (1.47-2.23) < 0.001 1.84 (1.50-2.26) < 0.001

No 234 (58.2) 11

Family history of CRC

Yes 46 (11.0) 1.58 (1.14-2.19) 0.0041 1.54 (1.11-2.14) < 0.001

No 372 (89.0) 11

Haemorrhoids

Yes 219 (55.2) 0.92 (0.75-1.12) 0.443 ––

No 178 (44.8) 1

Table IV. Analysis of participants in which screening detected an advanced neoplasm

Bivariate analysis Multivariate analysis

n (%) OR (95% CI) p-value OR (95% CI) p-value

Sex

Men 106 (67.5) 2.41(1.57-3.70) < 0.001 2.47(1.59-3.83) < 0.001

Women 51 (32.5) 11

Age (years)

60-69 79 (50.3) 1.14 (0.85-1.40) 0.5062 1.10 (0.72-1.69) 0.650

50-59 78 (49.7) 11

Rectal bleeding

Yes 54 (43.2) 1.13 (0.71-1.80) 0.5767 ––

No 71 (56.8) 1

Family history of CRC

Yes 22 (15.4) 1.97 (0.99-3.94) 0.0366 1.98 (1.02-3.84) 0.043

No 121 (84.6) 11

Haemorrhoids

Yes 58 (50.4) 1.34 (0.86-2.10) 0.211 ––

No 57 (49.6) 1

08. OR 1601 NAVARRO:Maquetación 1 28/12/09 08:04 Página 858

risk population, it is important to apply the quality mea-

sures required to guarantee that the screening is performed

in individuals with eligibility criteria. The questionnaires

may provide sufficient information to make it possible to

detect individuals at higher risk, even although this entails

an increase in difficulty and cost when dealing with screen-

ing programmes for large populations.

One of the important points to be investigated is if

some symptoms may suggest the presence of CRC and

because of that a diagnosis procedure should be indicated

instead of a population screening. However, it is difficult

to diagnose CRC because symptoms may be diffuse

(3,14), and associated gastrointestinal distress is frequent

in the general population (15,16). Rectal bleeding is a

nonspecific symptom and may be due to different condi-

tions, most of them benign, such as haemorrhoids or anal

fissures (the most frequent), and also malignant, such as

colorectal cancer. Although 40% of patients with CRC

report rectal blood loss, the risk of CRC in a patient with

rectal bleeding is low (17-19). On assessing the symp-

toms, gender and age differences in risk of CRC must be

taken into account. In the study of Lawrenson and associ-

ates (16) men with symptoms were more likely to be di-

agnosed with CRC than women.

There are few published studies that investigate the pres-

ence of symptoms in the population subjected to screening.

Although rectal bleeding is a predictive symptom of col-

orectal cancer in the population with screening sigmoi-

doscopy, a majority of cancers and adenomas in this group

were detected in individuals who were asymptomatic (20).

Ahmed et al. (21) demonstrated, in a CRC screening pilot

study, that lower gastrointestinal symptoms are common

among individuals who have a positive FOBT. However,

symptoms were not related to colonoscopy findings. In our

study, approximately 42% of patients with no findings at

colonoscopy or with non-neoplastic polyps reported rectal

bleeding. According to the authors, possible explanations

for the high prevalence of symptoms may include that these

patients respond to screening more than those actually

asymptomatic, or else that intestinal symptoms are frequent

in the general population. Our data, in agreement with the

literature, show that rectal bleeding was present in 43.2% of

those diagnosed with an advanced neoplasm, was more fre-

quent in men than in women, and in people aged between

50 and 59 years more than among those between 60 and 69

years. However, rectal bleeding was not associated with a

higher risk of advanced neoplasm (OR = 1.13, 95% CI,

0.71-1.80). As reported by Ahmed et al. (21), the presence

of rectal bleeding alone, as investigated in our screening

programme questionnaire, without taking into account the

actual characteristics of this or whether there were other

symptoms present, may increase the sensitivity of the test

without significantly predicting the diagnosis of advanced

neoplasm.

Individuals with a family history of CRC have a high

risk of developing the disease (5), which increases when

it is associated with early age of onset or multiple affect-

ed relatives (22-24). Colonoscopy surveillance has been

shown to reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal

cancer, not only in families with a history of hereditary

nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) (5,23) but also

in individuals with a moderate risk due to a family histo-

ry but not fulfilling any of the Amsterdam or Bethesda

criteria (23-25). In families at moderate risk, it is recom-

mended that colonoscopy surveillance be initiated at the

age of 45-50 years, since the likelihood of detecting an

advanced neoplasm in people under the age of 45 is very

small (23,24,26-28). In our study, the presence of a fami-

ly history of CRC without HNPCC criteria is associated

both with a positive result of FOBT and a diagnosis of

advanced neoplasm.

Although our results are similar to others already pub-

lished in the literature (21-24,28), they must be assessed

within the context of a prospective study of a question-

naire with some limitations. In the first place, as the ques-

tionnaires were only sent once to participants in both

rounds, it was implicitly assumed that the responses

would be the same after two years. Secondly, no other

symptoms other than rectal bleeding were considered. In

the third place, the questionnaire investigated the exis-

tence of relatives with three types of cancer, allowing the

screening of individuals with family history without tak-

ing into account that the risk of CRC varies according to

age at diagnosis, type of relative, and number of relatives

affected. These data suggest that the characteristics of our

questionnaire probably allowed the screening of individ-

uals with a greater risk of developing colorectal disease.

In fact, and as a result of the findings of this study, we

have modified the questionnaire to be sent to the candi-

date individuals in coming rounds. In addition to rectal

bleeding, the presence of other symptoms in the previous

3-6 months will be evaluated, such as changes in bowel

habit, abdominal pain and anaemia due to iron depletion.

In terms of family history, the number, age and the degree

of relationship of family members with CRC will be in-

vestigated. Depending on the response, we will exclude

non-candidates from the screening programme and refer

them to more specific measures.

The complexity involved in the development of

screening programmes in CRC in large populations com-

pels us to ascertain all the factors into which the popula-

tion may be grouped for different types of screening or

age of onset according to the risk of developing the dis-

ease. Among these factors, mention may be made of the

higher incidence of CRC in males and at an earlier age

(29), and the greater risk in the presence of a history of

CRC in first-degree relatives (27,28,30). These results

may therefore have important implications for the offer

of CRC screening programmes and their optimisation in

terms of cost effectiveness (31).

In summary, CRC population screening programmes

should be offered to eligible individuals using appropri-

ate instruments that make it possible to adapt the type of

screening to the risk of individuals to be screened. The

Vol. 101. N.° 12, 2009 COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING: STRATEGIES TO SELECT 859

POPULATIONS WITH MODERATE RISK FOR DISEASE

REV ESP ENFERM DIG 2009; 101 (12): 855-860

08. OR 1601 NAVARRO:Maquetación 1 28/12/09 08:04 Página 859

6

6

1

/

6

100%