FEA TUR ES /R

357

CANADIAN ONCOLOGY NURSING JOURNAL � VOLUME 25, ISSUE 3, SUMMER 2015

REVUE CANADIENNE DE SOINS INFIRMIERS EN ONCOLOGIE

FEATURES/RUBRIQUES

ABstrAct

Family members have multiple roles when

caring for someone diagnosed with can-

cer. The burden associated with these roles

can result in family members experienc-

ing elevated levels of emotional distress

including depression, anxiety, and physical

complaints. For comprehensive psychoso-

cial care to be all inclusive, the well-being

and distress levels of family members must

also be addressed. To date, little is known

about the speci c sources of distress for

family members.

The purpose of this research study was

to ll this gap. Speci cally, the researchers

developed a unique screening tool to iden-

tify sources contributing to family mem-

bers’ emotional distress. The study was

conducted in three phases: 1) a compre-

hensive literature review was done to elicit

a rst set of items, 2) two separate focus

groups of health care professionals and

family members were held to obtain their

feedback on possible items that would com-

prise the tool and, 3) a sample of family

members was invited to speak to the rele-

vancy of the proposed items. Results from

these analyses led to a tool comprising 46

items. Family member responses on these

items suggested that they are often con-

fronted with unique sources of distress

including those related to self-care, patient

care, and relational.

Cancer a ects the entire family.

While emotional distress experi-

enced by cancer patients is widely

studied (Graves et al., 2007; McLean

& Jones, 2007; Sellick & Edwardson,

2006; Zabora, BrintzenhofeSzoc,

Curbow, Hooker, & Piantados, 2001),

the distress of the family members is

often overlooked. Yet, the rates of dis-

tress experienced by family members

of oncology patients have been shown

to be elevated. For instance, using

the Distress Thermometer, a team of

researchers reported that 29.2% and

18% of family members of oncology

patients experienced moderate and high

levels of distress respectively (Zwahlen,

Hagenbuch, Carley, Recklitis, & Buchi,

2008).

Additionally, research suggests that

family members’ distress tends to

increase during speci c time points

across the disease trajectory (Murray

et al., 2010). Finally, a patient’s overall

coping is said to be positively related to

the well-being of the family members

(Northouse, 2012). Based on the

population of family members seen in

our psychosocial oncology program, we

argue that comprehensive patient care

must also take into account addressing

the needs of family members who are

directly involved in the cancer experience

of their loved one. At present, all new

patients and family members who

are seen by a clinician in the program

are invited to complete the Canadian

Problem Checklist (CPC) (Cancer

Journey Action Group, 2009) to help

identify the sources of their distress.

While the CPC was not speci cally

designed for family members, we were

using it to obtain some information on

what they identi ed as sources of distress

for them. Family members had noted

and provided us with feedback that they

felt the tool was not entirely applicable

to them. They felt that not all of their

sources of distress were identi ed, or

they felt the sources of distress listed

were very patient-speci c. In order to

address this concern, we recognized that

the development of a screening tool for

these family members was a necessary

rst step in the provision of optimal care

to these family members.

The purpose of the present study was

to develop a screening tool designed

to identify the distress level of family

members with a list of their speci c con-

cerns. The study was completed in three

phases. First, a comprehensive litera-

ture review was conducted on sources

contributing to emotional distress in

family members. Second, separate

focus groups of health care profession-

als in oncology and family members of

cancer patients were conducted. Goals

of these focus groups were to: 1) review

the preliminary items generated from

the literature review, 2) solicit sugges-

tions of additional or removal of items

and, 3) provide feedback on the Family

BrieF communicAtion

Comprehensive psychosocial care of cancer

patients: Screening for distress in family members

by Anita Mehta and Marc Hamel

ABout tHe AutHors

Anita Mehta, RN, PhD, Clinical Nurse Specialist and Co-Director, McGill University

Health Centre, Montreal, QC

Marc Hamel, PhD, Clinical Director, Psychosocial Oncology Program, McGill

University Health Centre, Montreal, QC

Correspondence: Anita Mehta, 1650 Cedar Avenue T6-301, Montreal, QC

Tel: 514 934-1934 ext 44815; Fax: 514 934-8593; Email: [email protected]

FundinG AcKnoWledGement

The Nursing Research Development Fund, with the generous support of the Newton Foundation and

matching funds provided by the Montreal General Hospital, Royal Victoria Hospital and Montreal Children’s

Hospital Foundations (McGill University Health Centre).

358 Volume 25, Issue 3, summer 2015 • CanadIan onCology nursIng Journal

reVue CanadIenne de soIns InfIrmIers en onCologIe

FEATURES/RUbRiqUES

Member Problem Checklist (FMPC).

These focus groups were audio-taped

and transcribed. The content of these

groups were coded and relevant themes

were extracted. Finally, a sample of

N=106 family members recruited from

oncology clinics were asked to rate the

relevancy of the FMPC items to their

overall experience.

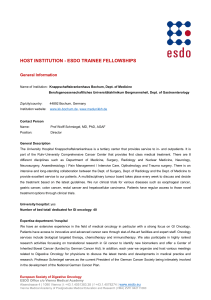

The screening tool resulted in 46

items (see Figure 1). The results of

this research indicated that, like can-

cer patients, family members reported

sources of distress related to practi-

cal (e.g., transportation/parking), emo-

tional (e.g., anxiety/worry), social/

family (e.g., lack of support), informa-

tional (e.g., about prognosis) and spir-

itual domains (e.g., faith). However,

family members also reported unique

sources of distress relevant to them

including those related to relational

(e.g., relationship with the patient),

self-care (e.g., managing one’s own

time) and patient-care (e.g., managing

patient’s symptoms).

The study also asked participants to

respond to qualitative questions pertain-

ing to their experience in completing

the screening items. Many felt strongly

that the new “checklist covers most con-

cerns a family member might have” and

that it was “clear” and “easy to read.”

The average time of completion was 7.6

minutes and a range of time needed to

complete the FMPC, from 30 seconds to

20 minutes was noted by reading their

qualitative responses. These responses

on the qualitative questions suggested

that the FMPC was easy for them to

complete and they found to be a mean-

ingful tool for them.

Family members are often consid-

ered the “hidden patient” in oncology

settings. They are often required to

deliver dierent types of care to patients,

without any former training and recog-

nition, and are expected to be continu-

ously supportive during the patient’s

illness. As a result, family members can

become easily overwhelmed, anxious

and/or depressed. The development of

this clinical tool specically designed to

screen for the sources of distress expe-

rienced by family members is the rst

step towards a more comprehensive

assessment of their distress and, likely,

that of the patient. This assessment/

screening places nurses, and all health

care professionals, in a stronger posi-

tion to provide optimal support and

appropriate family interventions in the

future.

reFerences

Cancer Journey Action Group (2009). Guide

to implementing screening for distress, the

6th vital sign: Moving towards person-

centered care. Retrieved from www.

canadianpartnershipagainstcancer.ca

Graves, K.D., Arnold, S.M., Love, C.L.,

Kirsh, K.L, Moore, P.G., & Passik,

S.D. (2007). Distress screening in a

multidisciplinary lung cancer clinic:

Prevalence and predictors of clinically

signicant distress. Lung Cancer, 55(2),

215–224.

McLean, L.M., & Jones, J.M. (2007). A

review of distress and its management in

couples facing end-of-life cancer. Psycho-

Oncology, 16(7), 603–617.

Murray, S.A., Kendall, M., Boyd, K., Grant,

L., Highet, G., & Sheikh, A. (2010).

Archetypal trajectories of social,

psychological, and spiritual wellbeing

and distress in family care givers of

patients with lung cancer: Secondary

analysis of serial qualitative interviews.

British Medical Journal, 340, 2581.

Northouse, L.L. (2012). Helping patients

and their family caregivers. Oncology

Nursing Forum, 39(5), 500–506.

Sellick, S.M., & Edwardson, A.D. (2006).

Screening new cancer patients for

psychological distress using the hospital

anxiety and depression scale. Psycho-

Oncology, 16(6), 534–542.

Zabora. J., BrintzenhofeSzoc, K., Curbow,

B., Hooker, C., & Piantadosi, S. (2001).

The prevalence of psychological distress

by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology, 10(1),

19–28.

Zwahlen, D., Hagenbuch, N., Carley, M.I.,

Recklitis, C.J., & Buchi, S. (2008).

Screening cancer patients’ families

with the distress thermometer (DT): a

validation study. Psycho-Oncology, 17(10),

959–66.

Figure 1

Family Member Problem Checklist:

Please check all of the following items that

have been a concern or problem for you in the

past week, including today

Practical

Finances

Legal Issues

Transportation/Parking

Household duties

Taking care of others

Work/Studies

Managing my own time

Information

About the disease

About the treatment

About prognosis

About supportive resources

Communication

Acting as a spokesperson

Difficulty talking about certain topics

Emotional

Sadness

Anger/frustration

Anxiety/worry

Guilt

Feeling overwhelmed

Helplessness

Shock

Resentment

Mehta & Hamel, 2015

Social

Feeling alone

Lack of support

Expectations from others

Relational

Change in social roles

Relationship with patient

Relationship with health care team

Family dynamics

Spiritual

Faith

Meaning and purpose

Hope

Death/Dying

Self-Care

Sleep

Appetite

Concentration/Memory

Fatigue/Weakness

Intimacy/Sexuality

My own physical health problems

My own mental health problems

Finding time for myself

Coping

Patient Care

Managing patient symptoms

Managing patient medications

Organising patient appointments

Caring for the patient at home

Self-confidence as a caregiver

1

/

2

100%