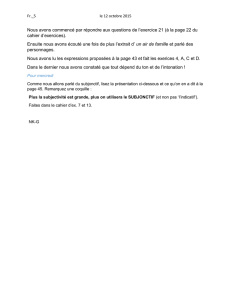

br@rh@Carlut/Meiden Vocabulaire, Chap

Page 1 sur 5

Version du lundi, 5 août, 2002 841060006

Le Vocabulaire du Carlut/Meiden, chap. 11

1

Le subjonctif (a)

1 a ball (i.e., an inflatable ball used in games) un ballon

2

2 a (solid) ball (e.g., a golf ball) une balle

3 a bullet une balle

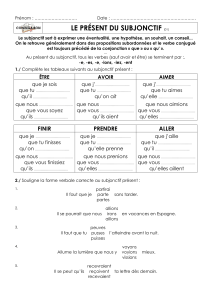

4 a subjunctive un subjonctif

5 an indicative un indicatif

6 to suggest suggérer

7 a stadium un stade

8 demanding exigeant

9 responsible responsable

10 an emotion une émotion

11 a certainty une certitude

3

12 it will rain (use the future tense) il pleuvra

13 to be in a hurry être pressé

Le subj. et l’indicatif (b)

14 in the negative au négatif

15 a creditor un créancier

16 to be astonished (reflexive verb) that he finished it s’étonner qu’il l’ait fini

4

17 to be in retirement être à la retraite

18 in Mexico au †Mexique

5

19 a doubt un doute

6

20 a baby un bébé

7

21 She is a judge. C’est un juge.

8

22 to Australia en †Australie

23 this guy ce {type|gars|mec}

9

24 I saw her the day before yesterday. Je l’ai vue avant-hier.

_______________

1

List compiled by John Robin Allen, St. John’s College, University of Manitoba, to be used in conjunction with Carlut &

Meiden, French for Oral and Written Review (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1993). Words in boldface type in the English are the

major parts of a given item, with the remaining words supplied for context, usually to clarify the meaning intended. Underlined

text in French then translates the corresponding boldface type expressions from the English side. Something bold and

underlined on the French side emphasises something you might overlook, such as that un exercice uses a “c” where English uses

an “s”. Braces and vertical lines, e.g., {alb}, indicate two or more valid answers to a question. One should learn at least one of

them, preferably the first, but the other answer(s) in the braces are equally acceptable, and one should be able to recognize them

and be able to translate them back into English. Answers in parentheses, e.g., « vivre (habiter, demeurer) » are either valid

expressions that do not fulfill the specific requirements of the question or are alternate forms that you may want to learn after you

have memorized the primary form. Words preceded by a dagger (e.g., « le †quartier †latin ») require the specific capitalization

shown. An arrow pointing down (↓) in the English indicates that the question did not fit into the line so it continues onto the next

line. Abbreviations used when space is a problem: « qqch » = quelque chose. « qqun » = quelqu’un.

Comments on this list are welcome and should be sent to [email protected]anitoba.ca.

2

Pour traduire «a (hot air) balloon», dites «un mongolfier». [En 1783, les frères Mongolfier réussirent la première ascension

d’un aérostat (ballon à air chaud).]

3

La terminaison «-tude» indique le féminin.

4

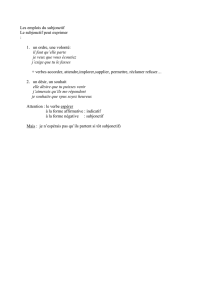

Les verbes qui expriment une émotion sont suivis du subjonctif.

5

En général, les pays dont le nom se terminent par un «-e» sont féminins (la France, la Suède, etc., en contraste avec le

Danemark, le Canada), mais le Mexique, le Cambodge et le Zaïre sont des exceptions à cette règle-là, et depuis la fin du 1997, le

Zaïre s’appelle «la République démocratique du Congo».

Si l’on dit «Mexico» en français, cela désigne ce qu’on appelle «Mexico City» en anglais.

6

«Sans doute»: ‘no doubt’.

7

Ce mot est masculin, même s’il s’agit d’un bébé fémelle. Par contre, «un/e enfant» peut être masculin ou féminin, selon le

cas.

8

«Un juge» est toujours masculin, même si c’est une femme. C’est le même cas avec «un auteur», «un bébé», «un notaire»,

«un prodige» et «un rat». Par contre, «une personne», «une vedette», «une star», «une souris» (‘a mouse’) et «une sentinelle» (‘a

sentry’) sont toujours féminines, même quand on parle d’un être masculin. Pour distinguer le sexe on emploie des adjectifs: «un

rat femelle» ou «une souris mâle».

9

On emploie « ce type » plus que « ce gars ». « Mon mec » : ‘my man’; « un beau mec » : ‘a gorgeous guy’.

Le Vocabulaire du Carlut/Meiden, chapter 11 Page 2 sur 5

Le subj. et l’infinitif

25 instead of me au lieu de moi

26 downtown en ville

10

27 to be astonished to do {être étonné|s’étonner} de faire

28 to be astonished that he is coming {être étonné|s’étonner} qu’il vienne

11

29 a watch tells me the time une montre m’indique l’heure

12

30 to fear danger [3-word answer] craindre le danger (avoir peur du danger)

31 Italian (the language; show gender) l’†italien (m.)

13

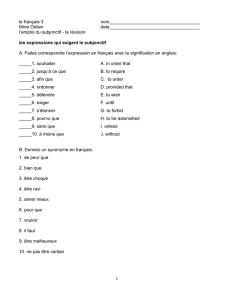

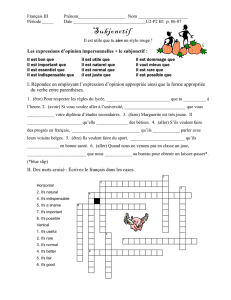

Les express. impers. et le subj

32 It is unlikely that Il est peu probable que

33 a reflection, thought (not «p..») une réflexion

14

34 to reflect on life [6-word answer] faire des réflexions sur la vie

35 imaginary imaginaire

36 to justify justifier

37 the subjunctive mood le mode subjonctif

15

38 Things are not all rosy. Les choses ne sont pas toutes roses.

39 to support (i.e., to help; give two translations) soutenir, appuyer

16

40 the troops la troupe

17

41 a diplomat un/e diplomate

42 a position une position

43 it is high time that il est grand temps que

44 the United Nations les †Nations unies

45 I am pleased to inform you about that matter. J’ai le plaisir de vous informer de cette

affaire.

18

46 to assure assurer

19

47 a peace une paix

48 to oblige obliger

49 to compromise compromettre

50 the Olympic games les Jeux Olympiques

Des phrases à traduire

51 a wife (not «f..») une épouse

52 a husband (not « m.. ») un époux

53 It is important that [3-word answer] Il importe que

20

54 a treaty un traité

55 surprising surprenant

56 hateful (4 possible answers; how many can you get?) {odieux|détestable|haissable|méchant}

21

57 a mirror reflects light un miroir reflète de la lumière

22

_______________

10

«A city center»: «un centre-ville».

11

«Vienne» est le subjonctif du verbe «venir», mais avec une majuscule (‘capital letter’) c’est aussi le nom de la capitale

d’Autriche (‘Vienna’).

12

Je donne cette question parce que le prochain exercice a le mot «watch», mais notez en passant que le verbe «indiquer»

traduit «to tell» quand il s’agit d’une montre, d’un livre, d’un manuel, d’un jauge (‘a gauge’), etc.

13

«L’Italien(ne)» (avec la majuscule «I») est une personne qui vient d’Italie.

14

«A reflection» dans un miroir est «un reflet», car le miroir peut «refléter» des images.

15

«Un mode» est un terme grammatical. «Une mode» traduit ‘a style’, ‘fashion’.

16

To second a motion: «appuyer une motion». To table a motion: «déposer une motion». To pass a motion: «adopter une

motion». To defeat a motion: «rejeter une motion».

Le verbe « supporter » s’emploie pour ‘to support [a weight]’ : « les colonnes du temple en supportent le toit ».

17

Plural in English, singular in French.

18

Pour traduire «to inform you that», dites «vous renseigner que».

19

«To reassure»: «rassurer».

20

Cette expression exige le subjonctif: «Il importe que vous fassiez cela.»

21

«Méchant/e» ne s’emploie pas beaucoup dans ce sens. Toutefois (‘in any event’) vous allez le voir employé ainsi dans le

prochain exercice: «It is surprising that he is so hateful».

22

Le verbe «refleter» se conjugue comme «préférer», avec les mêmes changements orthographiques. Notez, cependant, la

Le Vocabulaire du Carlut/Meiden, chapter 11 Page 3 sur 5

58 an energy une énergie

59 energetically [1-word answer] énergiquement

60 energetically [2-word answer] avec énergie

61 doubtful (give the masculine and feminine forms) douteux, douteuse

62 fantastic (not «for…») fantastique (formidable)

63 to go to the moon aller {dans|sur} la lune

64 This number is correct Ce chiffre est exact.

65 That is correct (not necessarily referring to a number) {Ça c’est |C’est} correct.

23

66 a foolish expression on his face une expression stupide au visage

67 a beast, animal une bête

24

68 a foolish personne une personne bête

69 a profession, trade (not «p..») un métier (une profession)

70 No profession is without merit [proverb] Il n’y a pas de sots métiers [proverbe]

71 a foolish (misguided) choice un choix idiot

72 to insult insulter

73 an airport un aéroport

Après «croire», «penser», etc

74 This colour suits her well. Cette couleur lui va bien.

75 That date suits me well. Cette date me convient bien.

25

76 to be worth valoir

77 That is not worth very much (not «... beaucoup») Cela ne vaut pas grand-chose

Les conjonctions du subjonctif

78 in order that Paul come (give two translations) afin que Paul vienne; pour que Paul

vienne

26

79 provided that we are (give two translations) pourvu que / à condition que nous soyons

80 without knowing it sans le {savoir|connaître}

81 without him knowing it sans qu’il le {sache|connaisse}

82 before he does it avant qu’il (ne) le fasse

27

83 until I understand him jusqu’à ce que je le comprenne

84 a penny {un sou|un centime}

28

85 to be hard of hearing être dur d’oreille

86 a lecturer (give masc. and feminine forms un conférencier; une conférencière

87 to take place avoir lieu

88 an optional course; an optional activity un cours facultatif; une activité facultative

29

89 whatever I do quoi que je fasse

30

90 a half (i.e., one of two parts) une moitié

31

91 three and a half (i.e., the fraction) trois et demi

32

différence entre le nombre d’accents en «refléter» et en «réfléchir».

23

D’autres traductions seraient «C’est bon» ou «C’est exact».

24

«Une bête à Bon Dieu»: ‘a ladybug’. «Chercher la petite bête»: ‘to nitpick’.

25

Pour traduire le verbe «to suit» en parlant des couleurs, des vêtements, etc., employez une forme du verbe «aller». Pour

les dates, le climat, les arrangements, etc. employez plutôt une forme de «convenir».

26

«That Paul come» est le subjonctif en anglais.

27

Après «à moins que» et «avant que» on peut employer un «ne» pléonastique qui ne se traduit pas.

28

En principe il y avait vingt sous (ou cent centimes) dans un franc, mais les centimes, les sous et les francs n’existent plus.

29

Employez «au choix» pour traduire «optional» quand il s’agit de couleurs, de taille, de vêtements.

30

Ne confondez pas la conjunction «quoique» (‘although’) avec le pronom indéfini «quoi que» (‘whatever’): «Quoi que je

fasse, je ne gagne rien aux T.L.V.» (‘Whatever I do, I win nothing at the V.L.T.’). [T.L.V.: «Terminus lotto et vidéo».]

31

Les noms abstraits qui se terminent par «-té» ou «tié» sont féminins: « la bonté ». «la pitié», «une amitié», etc.

«Travailler en collaboration, cela veut dire prendre la moitié ce son temps à expliquer à l’autre que ses idées sont stupides.»

(Wolinski)

32

Le mot «demi» s’accorde avec un substantif qui le précède: «trois heures et demie», mais si l’on attache «demi» avec un

trait d’union devant le substantif, il n’y a pas d’accord: «une demi-heure».

Le Vocabulaire du Carlut/Meiden, chapter 11 Page 4 sur 5

Des phrases à traduire

92 to go away s’en aller

93 Beat it! {Va t’en|Allez-vous en}!

94 to anger someone (4 possible answers; how many can you get?) {vexer|fâcher|irriter|enrager} quelqu’un

95 How can we leave? [2-word answer] Comment partir ?

96 truly (not «s..») vraiment

97 sincerely, truly sincèrement

Le subjonctif du doute

98 a dentist un/e dentiste

99 to be willing vouloir bien

100 to sacrifice oneself for an ideal se sacrifier pour un idéal

101 to interest you {vous intéresser|t’intéresser}

Des phrases à traduire

102 capable capable

103 to solve a problem résoudre un problème

104 to type [4-word answer] taper à {la machine|l’ordinateur}

105 near here près d’ici

106 a shopping center un centre commercial

107 to risk one’s life to save someone from a danger risquer sa vie pour sauver qqun d’un danger

108 to be very up to date about these things être très {au courant|à la page} de ces choses

Des phrases avec superlatifs

109 a building (not «b..») un édifice

33

110 Whoever he is (not «Quel ..») Qui qu’il soit

111 Whoever / Whatever he is (not «Qui ..») Quel qu’il soit

112 However happy he may be Si {heureux|content} qu’il {puisse être|soit}

113 a preference une préférence

114 some young men {des|quelques} jeunes gens

34

115 to, in France en †France

116 a religion (e.g., catholic, protestant, etc.) une religion

117 a religion (e.g., Christianity, Islam, Judaism, etc.) une foi

35

118 Whatever your religion Quelle que soit {ta|votre} religion

119 lazy (give both the masculine and feminine singular forms) paresseux; paresseuse

120 However that may be Quoi qu’il en soit

121 Wherever he goes Où qu’il aille

122 a destiny (not «s..») {un destin|une destinée} (un sort)

123 against contre

124 on the contrary au contraire

125 a good (i.e., well-behaved) child un enfant sage

36

126 of the same opinion (not «.. opinion») du même avis

127 a copy; composition; paper une copie

128 He is artistic (refers to temperament, personality) Il est artiste.

129 He is artistic (refers to one’s ability in art or acting) Il est artistique.

130 a (male) Hungarian un †Hongrois (une Hongroise)

131 a fox un renard

132 a paper (i.e., a newspaper) un journal

_______________

33

An apartment building : « un immeuble ».

34

Pour exprimer le partitif (‘some’) quand un adjectif précède un substantif, on change le «des» en «de»: «J’ai des livres»,

«J’ai de bons livres.» Cependant, quelques expressions précédées par un adjectif sont si communes qu’on les considère comme

un simple substantif sans adjectif, et on garde le «des»: «des jeunes gens», «des jeunes filles», «des petits pois», «des grands

magasins».

35

On parle de «la foi chrétienne» ou «la foi musulmane», mais pour parler des différentes branches d’une religion, on parle

de «la religion catholique» ou «la religion protestante».

36

«Sage»: ‘wise’.

Le Vocabulaire du Carlut/Meiden, chapter 11 Page 5 sur 5

133 a tendency une tendance

37

134 liberal libéral

135 a possibility une possibilité

136 a leaf, sheet une feuille

137 an exit une sortie

138 to steal voler

38

«notice» à «people»

139 an uneasiness (not m..) une inquiétude (une malaise)

140 an opportuneness une opportunité

141 to print a book {imprimer|faire imprimer} un livre

142 to offend (not «b..») {offenser|offusquer}

39

143 a scruple un scrupule

144 full of people (not «.. g..») plein de monde (plein de gens)

145 an Italian [2-word answer] un †Italien (une †Italienne)

146 a very musical people un peuple très musicien

147 the snow la neige

148 a thesis une thèse

Des phrases à traduire

149 (light) purple mauve

150 crimson pourpre

40

151 dark (when referring to a color) foncé

152 a history une histoire

153 a briefcase une serviette

41

154 a (female) director of a firm une directrice d’une entreprise

155 the head of an organization le chef d’une organisation

156 a (film) director {un metteur en scène|un/e cinéaste}

157 a reception une réception

158 a composition, paper, essay (starts with «d..») une dissertation

159 a review un {compte rendu|compte-rendu}

42

_______________

37

Presque tout nom qui se termine par «-ance» ou en «-ence» est féminin: «une chance», «une connaissance», etc.

38

Une autre traduction du mot «voler» est «to fly».

39

J’attends le mot le plus simple, «offenser», mais j’accepte «offusquer» aussi. Une réaction plus forte serait «outrager». La

traduction qui commence par «b…» est «blesser».

40

Ne confondez pas le mot «pourpre» avec l’anglais «purple». Pensez au poème de Ronsard, « Ode à Cassandre » où, en

parlant d’une rose, le poète dit « [la rose] qui ce matin avait déclose, / sa robe de pourpre au soleil ». (He obviously did not write

that the rose had shown its dress of “purple” to the sun.) Pour traduire «purple», employez «violet» (‘dark purple’) ou «mauve»

(‘light purple’, ‘mauve’).

41

Connaissez-vous deux autres traductions du mot «serviette»?

42

On peut écrire cette expression avec ou sans un trait-d’union (‘hyphen’): «un compte-rendu» ou «un compte rendu».

1

/

5

100%