Collaboration entre le cœur et le cerveau : la réadaptation cardiaque

Avant-propos

Collaboration entre le cœur et le cerveau : la réadaptation

cardiaque complète pour la prise en charge des maladies

vasculaires chroniques et la prévention secondaire suivant

un AIT ou un AVC léger non débilitant

Peter L. Prior, PhD1,4 Neville Suskin, MD1,4 Vladimir Hachinski, DSc.2,4

Richard Chan, MD2,4 Karen Unsworth, MSc1 Sharon Mytka, M.Ed.3,4

Dinesh Kabra, MD5 Cheryl Mayer, MScN2,4 Christina O’Callaghan, B.App.Sc.(PT)6

1Programme de réadaptation cardiaque et de prévention secondaire; 2Clinical Neurological Sci-

ences et 3Southwestern Ontario Stroke Strategy au London Health Sciences Centre; 4Université

Western Ontario; London (Ontario); 5Central India Institute of Medical Sciences, Nagpur,

Inde; 6Ontario Stroke Network

Les accidents vasculaires cérébraux (AVC) sont

responsables de 15 000 à 20 000 admissions à

l’hôpital en Ontario et étant donné leur taux

de récurrence annuel qui varie de 4 à 14 %, la

prévention secondaire devient alors une priorité1-3.

Les accidents ischémiques transitoires (AIT),

événement semblable aux AVC, se résorbent en

moins de 24 heures1.

Les maladies cérébrovasculaires et les

coronaropathies ont en commun des facteurs

importants en ce qui concerne la pathophysiologie

et leurs résultats. Il arrive souvent que les patients

qui présentent un AIT ou un AVC non débilitant

d’intensité légère soient atteints d’athérosclérose

dans tout l’appareil vasculaire ou d’une maladie

cardiovasculaire comorbide et qu’ils soient

exposés à un risque plus élevé de présenter un AVC

récurrent ou un événement cardiovasculaire2,4-7.

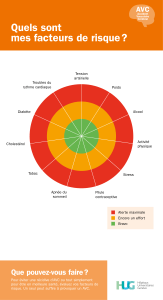

Les coronaropathies, les AIT ou les AVC ont

en commun de nombreux facteurs de risque

modiables au niveau de l’appareil vasculaire, y

compris l’inactivité physique, l’hypertension, le

bilan lipidique anormal, l’usage du tabac, l’obésité

ou le surpoids, le diabète sucré, le stress et la

dépression2,8-15.

Or, il n’est pas étonnant de constater que dans les

lignes directrices actuelles, fondées sur la médecine

factuelle et ciblant la prévention secondaire après

un AVC ou à un AIT, le syndrome coronarien

aigu et la réadaptation cardiaque se chevauchent

de façon considérable16-18. Un examen des méta-

analyses de la prévention secondaire a conclu

qu’au moins 4/5 des événements vasculaires

récurrents chez les patients souffrant d’une

maladie cérébrovasculaire pourraient être évités

moyennant une stratégie multifactorielle intégrale,

y compris les interventions pharmacologiques et

comportementales19.

Le traitement de réadaptation cardiaque

complète des patients souffrant d’une maladie

cardiaque est souvent rentable à la suite d’un

événement cardiaque. Les patients atteints d’une

maladie cérébrovasculaire pourraient bénécier

potentiellement d’une approche multifactorielle

intégrée; il pourrait y avoir des raisons

convaincantes d’ordre scientique, clinique et

économique pour envisager la réadaptation

cardiaque comme stratégie de prévention

secondaire suivant un AIT ou un AVC d’intensité

légère. En effet, une étude antérieure portant sur

des patients ayant subi un AVC complet d’un à 12

ans auparavant, ont démontré une amélioration

des facteurs de risque et de l’état psychologique

au terme d’un traitement de réadaptation

cardiaque complète20. À notre connaissance,

cependant, il n’y a pas eu d’investigations sur

le déploiement de la réadaptation cardiaque

relativement tôt après un AIT ou un AVC non

débilitant d’intensité légère. Nous avons admis

comme hypothèse qu’un programme complet de

réadaptation cardiaque, en collaboration avec la

clinique de prévention des AVC, pourrait offrir

une prévention secondaire rentable et efcace

suivant un AIT ou un AVC d’intensité légère,

sans redoublement des infrastructures et des

expertises.

Pour vérier si un programme complet de

réadaptation cardiaque pour la prévention

secondaire chez les patients atteints d’un AIT

ou d’un AVC d’intensité légère est rentable et

efcace, une étude pré-pilote et post-pilote

a été effectuée. Les critères d’admissibilité

comprenaient la présence d’un AIT ou d’un AVC

Description de la méthode de l’étude

pilote

ACRC ACRC ACR

Aspects psychosociaux de la réadaptation cardiaque 13

non débilitant d’intensité légère au cours des

12 derniers mois et d’au moins un facteur de

risque vasculaire. De janvier 2005 en avril 2006,

des sujets ayant donné leur consentement ont été

recrutés consécutivement au sein de la population

de patients des cliniques d’urgence spécialisées

dans les AIT afliées aux cliniques de prévention

secondaire du centre hospitalier London Health

Sciences Centre (LHSC). Les sujets ont reçu les

soins médicaux de routine proposés par la clinique

de prévention secondaire. Les soins de routine

ont observé les lignes directrices de la Fondation

des maladies du cœur du Canada concernant

la stratégie coordonnée relative aux pratiques

optimales de soins de l’AVC et les participants à

l’étude et leur médecin de famille recevaient des

conseils sur la prévention secondaire normale

visant l’adhésion à des facteurs de risque ciblés,

y compris la pratique de l’exercice physique. De

plus, on a inscrit les sujets à l’Université Western

Ontario et au programme de réadaptation

cardiaque et de prévention secondaire du LHSC,

lequel intègre la prise en charge médicale à

des services structurés d’exercices, de régime

alimentaire et de consultation psychologique

(gestion du stress, traitement 1:1, cessation

du tabac), sous un contrôle de 6 mois pris en

charge par un inrmier / une inrmière. Au

stade initial et nal du programme, on a effectué

une mesure normalisée des facteurs suivants

: capacité aérobique, prol lipidique, tension

artérielle, glycémie, indice de masse corporelle,

tour de la taille, cessation du tabac, dépression,

anxiété et la qualité de vie associée à la santé.

Nous avons également évalué la fonction

cognitive à l’aide d’une courte batterie de tests

neuropsychologiques.

Dans l’ensemble, cet échantillon de sexe mixte

nous a permis d’obtenir des améliorations

importantes tant sur le plan statistique que

clinique au niveau de la capacité d’exercice

physique, du prol lipidique, de l’anthropométrie,

des scores liés aux paramètres psychologiques et

à la qualité de vie, à l’exception toutefois de la

tension artérielle. Le risque de mortalité, calculé

d’après les résultats de l’épreuve d’effort sur tapis

roulant Duke (Duke Treadmill Score), a baissé

de façon signicative. Nous avons constaté des

regains importants dans l’exécution de tests

neuropsychologiques sensibles à la vélocité

psychomotrice, à l’apprentissage verbal, à la

mémorisation et à la facilité verbale. Les résultats

de l’étude pilote ont été présentés plus tôt cette

année lors du congrès mondial sur les AVC et sont

maintenant en préparation pour être publiés21.

Cet essai nous permet de conclure qu’une

réadaptation cardiaque complète est à la fois

rentable et efcace comme stratégie de prévention

secondaire suite à un AIT / AVC d’intensité

légère. Nous avons fait le rapprochement efcace

entre deux services cliniques différents. Nous

avons obtenu des améliorations importantes

sur le plan clinique et statistique relativement

à des facteurs de risque vasculaire clé. Même

si la réplication et le contrôle sont nécessaires,

nous avons également obtenu des preuves

préliminaires intéressantes selon lesquelles la

réadaptation cardiaque est en mesure d’améliorer

les résultats neuropsychologiques suite à un AIT

ou un AVC d’intensité légère, ce qui recèle une

pertinence potentiellement importante pour le

pronostic et la capacité fonctionnelle.

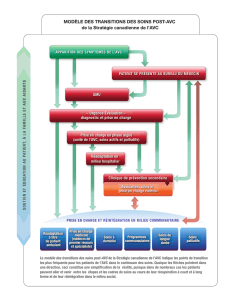

Nous croyons que ce projet novateur

exemplie les principes clé du modèle des

maladies chroniques de Wagner Chronic Disease

Model22. Le centre de prévention secondaire et

le programme de réadaptation cardiaque et de

prévention secondaire du LHSC ont collaboré

avec succès à la prestation de soins intégrés

complets pour les maladies vasculaires chroniques

et la prévention. La restructuration du mode

d’administration des soins, ce qui nous a permis

de transcender les structures traditionnelles,

inue sur la coordination interprofessionnelle

entre les services cliniques et soutient la prise en

charge autonome du patient. Les fournisseurs

de soins de santé ont pu proter d’un soutien

décisionnel grâce à la disponibilité de lignes

directrices fondées sur la médecine factuelle,

qui servait également à informer notre stratégie

d’évaluation. À partir de notre expérience avec

le présent essai, nous avons pu enregistrer

dorénavant dans notre système électronique de

gestion des patients des facteurs de risque ciblés

et des recommandations factuelles relatives à la

médication requise pour les AIT / AVC. L’essai

a su exploiter les ressources communautaires par

la tenue de ses programmes d’exercices au centre

local du YMCA. Notre liaison avec les soins

primaires s’est exprimée sous forme de résumés

des progrès du patient à son entrée et à sa sortie

du programme et ce, pour les facteurs

Résultats de l’étude pilote

Pertinence pour la pratique médicale

14 Aspects psychosociaux de la réadaptation cardiaque

ACRC ACRC ACR

Recherche en cours

de risque ciblés engendrés et documentés par

notre système électronique de gestion des

patients.

À notre avis, les facteurs de succès clé

comprenaient les éléments suivants : 1)

coordination inter-service dévouée et réunions

mensuelles du personnel du centre de prévention

secondaire et du programme de réadaptation

cardiaque et de prévention secondaire avec les

chercheurs; 2) processus systématique formel

de références; 3) mesure rigoureuse et stratégie

d’évaluation, intégrée dès le stade initial au plan

du programme; et 4) surveillance des progrès

des patients en temps réel orientée vers des

cibles thérapeutiques factuelles et l’adhésion des

praticiens aux lignes directrices actuelles fondées

sur la médecine factuelle.

À partir du présent essai sur la rentabilité et

l’efcacité, nous sommes actuellement en train

d’effectuer deux essais bicentriques contrôlés,

à répartition aléatoire, de concert avec nos

collaborateurs de l’Institut de cardiologie de

l’Université d’Ottawa (Dr Neville Suskin et Dr

Robert Reid, co-investigateurs principaux à

London et à Ottawa, respectivement), nancés

par la Fondation des maladies du cœur du Canada.

Dans cet essai, les sujets ont été répartis de façon

aléatoire à recevoir, soit les soins de routine

offerts par le centre de prévention secondaire

de chaque centre, soit les soins de routine avec

6 mois de réadaptation cardiaque complète à

l’instar de l’intervention proposée dans l’étude

sur la rentabilité et l’efcacité.

Financement: Le nancement de la présente

étude provient entièrement du Ministère de la

Santé et des Soins de longue durée de l’Ontario

par le biais de la Stratégie ontarienne de l’AVC

moyennant une subvention accordée aux co-

investigateurs principaux le Dr V. Hachinski et le

Dr N. Suskin.

Références :

Pertinence pour la pratique médicale

1.

2.

3.

4.

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. To-

wards an Integrated Stroke Strategy. 2000;45-48.

Wolf PA, Clagett GP, Easton JD, et al. Preventing isch-

emic stroke in patients with prior stroke and transient

ischemic attack : a statement for healthcare profession-

als from the Stroke Council of the American Heart As-

sociation. Stroke 1999;30:1991-4.

Hill MD, Yiannakoulias N, Jeerakathil T, et al. The high

risk of stroke immediately after transient ischemic attack:

a population-based study. Neurology 2004;62:2015-20.

Adams RJ, Chimowitz MI, Alpert JS, et al. Coronary

risk evaluation in patients with transient ischemic attack

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

and ischemic stroke: a scientic statement for health-

care professionals from the Stroke Council and the

Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart

Association/American Stroke Association. Circulation

2003;108:1278-90.

Roth EJ. Heart disease in patients with stroke: inci-

dence, impact, and implications for rehabilitation. Part

1: Classication and prevalence. Arch Phys Med Reha-

bil 1993;74:752-60.

Gordon NF, Gulanick M, Costa F, et al. Physical activ-

ity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors:

an American Heart Association scientic statement

from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Subcommit-

tee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention;

the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; the Council on

Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the

Stroke Council. Circulation 2004;109:2031-41.

van Wijk I, Kappelle LJ, van Gijn J, et al. Long-term

survival and vascular event risk after transient isch-

aemic attack or minor ischaemic stroke: a cohort study.

Lancet 2005;365:2098-104.

Mouradian MS, Majumdar SR, Senthilselvan A, et al.

How well are hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes,

and smoking managed after a stroke or transient isch-

emic attack? Stroke 2002;33:1656-9.

Suskin N, MacDonald S, Swabey T, et al. Cardiac re-

habilitation and secondary prevention services in On-

tario: recommendations from a consensus panel. Can

J Cardiol. 2003;19:833-8.

Goldstein LB, Adams, R, Appel L, et al. Primary pre-

vention of ischemic stroke: A statement for healthcare

professionals from the Stroke Council of the Ameri-

can Heart Association. Circulation 2001;103:163-82.

Pearson TA, Blair SN, Daniels SR, et al. AHA Guide-

lines for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Dis-

ease and Stroke: 2002 Update: Consensus Panel Guide

to Comprehensive Risk Reduction for Adult Patients

Without Coronary or Other Atherosclerotic Vascu-

lar Diseases. American Heart Association Science

Advisory and Coordinating Committee. Circulation

2002;106:388-91.

Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Association

of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocar-

dial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from

52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control

study. Lancet 2004;364:953-62.

Barnett PA, Spence JD, Manuck SB, Jennings JR. Psy-

chological stress and the progression of carotid artery

disease. J Hypertens 1997;15:49-55.

Lichtman JH, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, et al.

Depression and coronary heart disease: recommenda-

tions for screening, referral, and treatment: a science

advisory from the American Heart Association Pre-

vention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular

Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on

Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary

Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research:

endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Cir-

culation 2008;118:1768-75.

Everson SA, Roberts RE, Goldberg DE, Kaplan GA.

Depressive symptoms and increased risk of stroke

mortality over a 29-year period. Arch Intern Med

1998;158:1133-8.

Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. Guidelines for

ACRC ACRC ACR

Aspects psychosociaux de la réadaptation cardiaque 15

17.

18.

prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke

or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare

professionals from the American Heart Association/

American Stroke Association Councilon Stroke: co-

sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiol-

ogy and Intervention: the American Academy of Neu-

rology afrms the value of this guideline. Circulation

2006;113:409-449.

Smith SC Jr, Allen J, Blair SN, et al. AHA/ACC guide-

lines for secondary prevention for patients with coro-

nary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006

update: endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and

Blood Institute. Circulation 2006;113:2363-72.

Stone JA, Arthur HM, Second Edition. Canadian

Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Cardiovas-

cular Disease Prevention: Enhancing the Science, Re-

ning the Art, 2004. Canadian Association of Cardiac

Rehabilitation 2004; Winnipeg, Manitoba.

19.

20.

21.

22.

Hackam DG and JD Spence. Combining multiple

approaches for the secondary prevention of vascu-

lar events after stroke: a quantitative modeling study.

Stroke 2007;38:1881-5.

Lennon O, Carey A, Gaffney N, et al. A pilot ran-

domized controlled trial to evaluate the benet of the

cardiac rehabilitation paradigm for the non-acute isch-

aemic stroke population. Clin Rehabil. 2008;22:125-33.

Prior P, Suskin N, Hachinski V, Chan R, et al. Compre-

hensive cardiac rehabilitation for secondary prevention

after TIA/mild stroke: update on vascular risk factors,

psychological and neurocognitive outcomes. Interna-

tional Journal of Stroke 2008;3:s66.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving

chronic illness care: translating evidence into action.

Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20:64-78.

Le Canada compte de 40 000 à 50 000 cas

d’accidents vasculaires cérébraux (AVC) par

année1. Jusqu’à 75 % des victimes d’AVC ont des

antécédents de maladie cardiaque2. Les AVC et

les maladies cardiaques, tout particulièrement la

coronaropathie, ont en commun un grand nombre

de mécanismes pathophysiologiques sous-

jacents. Presque tous les facteurs de risque connus

sont communs à ces deux pathologies, à savoir,

l’hypertension, le tabagisme, l’hyperlipidémie,

le diabète, l’obésité, l’inactivité physique et le

stress2. Une maladie cardiaque sous-jacente, telle

que la brillation auriculaire, la cardiomyopathie

ou une cardiopathie valvulaire peuvent provenir

d’une cardioembolie responsable de jusqu’à 15 %

de tous les cas d’AVC.

La plupart des patients atteints d’un AVC

répondent aux critères de sélection pour la

réadaptation cardiaque, y compris l’éducation sur

la réduction du risque semblable à celle offerte

par les programmes bien établis de réadaptation

cardiaque auxquels participent de nombreux

patients cardiaques. De récentes études

démontrent qu’il est raisonnable de conclure que

les patients atteints d’un AVC peuvent participer

en toute sécurité à la réadaptation cardiaque3.

Un essai clinique, à répartition aléatoire, révèle

que les exercices aérobiques sur tapis roulant

améliorent la mobilité fonctionnelle ainsi que

la santé cardiovasculaire en présence d’un AVC

chronique plus efcacement que la réadaptation

cardiaque conventionnelle relativement aux

améliorations dans l’apport maximal en oxygène

et les épreuves de marche de 6 minutes4.

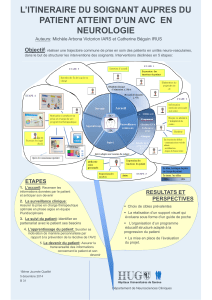

Actuellement, les victimes d’AVC ne sont pas

admises systématiquement à un programme de

réadaptation cardiaque à moins qu’ils présentent

une maladie cardiaque concomitante.

Les patients atteints d’un AVC ont des

restrictions uniques qui leur sont imposées par leur

état; les professionnels en réadaptation cardiaque

devraient reconnaître ce fait. Quoique les

principes classiques de la réadaptation cardiaque

demeurent, une adaptation individualisée de

ces programmes pourrait s’avérer nécessaire

pour maximiser la participation du patient au

programme de réadaptation cardiaque.

Étude de cas – AVC de l’artère cérébrale

droite centrale et réparation de la valvule mitrale

Monsieur T.M. est un professionnel âgé de 44

ans qui a souffert d’un AVC ischémique grave de

l’artère cérébrale droite centrale. Simultanément,

il présentait une endocardite bactérienne au

niveau de la valvule mitrale et, par conséquent, il

a dû subir la réparation de la valvule. Il a pris part

à un traitement considérable de réadaptation

Les maladies cardiaques et les AVC : Est-il possible de

combler les lacunes? – Observation de cas Les maladies

cardiaques et les AVC : Est-il possible de combler les

lacunes? – Observation de cas

Peter Ting, MBBS 1, 2; Carmen Catherine Tuchak, MD3,4; William Dafoe, MD 1,2

1Northern Alberta Cardiac Rehabilitation Program, Edmonton, AB; 2University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, AB; 3

University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB; 4Adult Stroke Program, Glenrose Rehabilitation Hospital, Edmonton, AB

16 Aspects psychosociaux de la réadaptation cardiaque

ACRC ACRC ACR

1

/

4

100%