Perinatal Mental Health Teams & Outcomes in Pregnant Women: England Study

Telechargé par

ghivi15

174

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 11 March 2024

Articles

Community perinatal mental health teams and associations

with perinatal mental health and obstetric and neonatal

outcomes in pregnant women with a history of secondary

mental health care in England: a national population-based

cohort study

Ipek Gurol-Urganci*, Julia Langham*, Emma Tassie, Margaret Heslin, Sarah Byford, Antoinette Davey, Helen Sharp, Dharmintra Pasupathy,

Jan van der Meulen†, Louise M Howard†, Heather A O’Mahen†

Summary

Background Women with a pre-existing severe mental disorder have an increased risk of relapse after giving birth. We

aimed to evaluate associations of the gradual regional implementation of community perinatal mental health teams

in England from April, 2016, with access to mental health care and with mental health, obstetric, and neonatal

outcomes.

Methods For this cohort study, we used the national dataset of secondary mental health care provided by National Health

Service England, including mental health-care episodes from April 1, 2006, to March 31, 2019, linked at patient level to

the Hospital Episode Statistics, and birth notifications from the Personal Demographic Service. We included women

(aged ≥18 years) with an onset of pregnancy from April 1, 2016, who had given birth to a singleton baby up to

March 31, 2018, and who had a pre-existing mental disorder, defined as contacts with secondary mental health care in the

10 years immediately before pregnancy. The primary outcome was acute relapse, defined as psychiatric hospital admission

or crisis resolution team contact in the postnatal period (first year after birth). Secondary outcomes included any

secondary mental health care in the perinatal period (pregnancy and postnatal period) and obstetric and neonatal

outcomes. Outcomes were compared according to whether a community perinatal mental health team was available

before pregnancy, with odds ratios (ORs) adjusted for time trends and maternal characteristics (adjORs).

Findings Of 807 798 maternity episodes in England, we identified 780 026 eligible women with a singleton birth, of

whom 70 323 (9·0%) had a pre-existing mental disorder. A postnatal acute relapse was found in 1117 (3·6%) of

31 276 women where a community perinatal mental health team was available and in 1745 (4·5%) of 39 047 women

where one was unavailable (adjOR 0·77, 95% CI 0·64–0·92; p=0·0038). Perinatal access to any secondary mental

health care was found in 9888 (31·6%) of 31 276 women where a community perinatal mental health team was

available and 10 033 (25·7%) of 39 047 women where one was not (adjOR 1·35, 95% CI 1·23–1·49; p<0·0001). Risk of

stillbirth and neonatal death was higher where a community perinatal mental health team was available (165 [0·5%]

of 30 980 women) than where it was not (151 [0·4%] of 38 693 women; adjOR 1·34, 95% CI 1·09–1·66; p=0·0063), as

was the risk of a baby small for gestational age (2227 [7·2%] of 31 030 women vs 2542 [6·6%] of 38 762 women;

adjOR 1·10, 1·02–1·20; p=0·016), whereas preterm birth risk was lower (3167 [10·1%] of 31 206 women vs 4341 [11·1%]

of 38 961; adjOR 0·86, 0·74–0·99; p=0·032).

Interpretation The regional availability of community perinatal mental health teams reduced the postnatal risk of

acute relapse and increased the overall use of secondary mental health care. Community perinatal mental health

teams should have close links with maternity services to avoid intensive psychiatric support overshadowing obstetric

and neonatal risks.

Funding The National Institute for Health and Care Research.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article under the CC BY 4.0 license.

Introduction

Women with a pre-existing mental disorder are at

increased risk of a recurrence or exacerbation of their

mental health problems during the perinatal period.1

For example, a 2016 systematic review2 showed women

with pre-existing bipolar disorder had more than

20% risk of relapse in the postnatal period. A previous

study3 that we carried out in England, which included

all women giving birth between 2014 and 2018, also

showed an increased risk of adverse obstetric, neonatal,

and maternal outcomes in women who had a

pre-pregnancy secondary mental health-care contact,

Lancet Psychiatry 2024;

11: 174–82

Published Online

January 23, 2024

https://doi.org/10.1016/

S2215-0366(23)00409-1

*Joint first authors

†Joint senior authors

Department of Health Services

Research and Policy, London

School of Hygiene & Tropical

Medicine, London, UK

(I Gurol-Urganci PhD,

J Langham PhD,

Prof J van der Meulen PhD);

King’s Health Economics

(E Tassie MSc, M Heslin PhD,

Prof S Byford PhD) and Section

of Women’s Mental Health

(Prof L M Howard PhD),

Institute of Psychiatry,

Psychology and Neuroscience,

and Department of Women

and Children’s Health

(Prof D Pasupathy PhD), King’s

College London, London, UK;

Department of Primary Care

and Mental Health, University

of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

(Prof H Sharp PhD);

Reproduction and Perinatal

Centre, Faculty of Medicine and

Health, University of Sydney,

Sydney, NSW, Australia

(Prof D Pasupathy); Washington

Singer Laboratories, University

of Exeter, Exeter, UK

(A Davey PhD,

Prof H A O’Mahen PhD)

Correspondence to:

Prof Jan van der Meulen,

Department of Health Services

Research and Policy, London

School of Hygiene & Tropical

Medicine, London WC1H 9SH,

UK

jan.vandermeulen@lshtm.

ac.uk

Articles

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 11 March 2024

175

with higher risks in women who had more recent

mental health-care contacts and in women who had a

contact that reflected a more severe mental health

disorder.

A guideline for the National Health Service (NHS) in

England, which was published in 2014, recommends that

women who have pre-existing complex and severe mental

illness should be referred to specialist mental health

services during pregnancy and the postnatal period,

preferably to a specialist community perinatal mental

health team for timely assessment and treatment.4,5 These

teams can counsel women planning a pregnancy and give

medication advice, oer psychological therapies, facilitate

bonding with the baby, and provide support for partners.6

Community perinatal mental health teams are also

expected to facilitate referral to the most appropriate

professionals in emergency situations. In 2016, NHS

England announced a 5-year investment of £365 million to

increase the overall availability of perinatal mental health

services, improve the treatment of women with new

mental health problems, and reduce the risk of relapse of

women with pre-existing mental disorders, particularly in

women at risk of severe acute relapses needing hospital

admission or the input of a mental health crisis resolution

team who provide intensive support in the community.7

The implementation initially prioritised areas that had

existing services that were not fully staed or areas that

already had robust service plans in place. Further

investment followed in 2019 with an aim to increase the

number of women for whom community perinatal

mental health teams are available during the perinatal

period and for pre-conception counselling.

We aimed to assess whether this gradual imple-

mentation of community perinatal mental health teams

was associated with an increase in the overall use of

secondary mental health-care services and a reduction

in the risk of acute relapse in the postnatal period.

Individuals are eligible to receive secondary mental

health care provided by NHS England if they have

complex, moderate, or severe mental health problems

that require a more intensive and specialist intervention

than primary care sta can provide. To access secondary

mental health care, patients typically need a referral from

a general practitioner or to be seen as part of urgent or

emergency psychiatric care.8 Because of the increased

obstetric and neonatal risk in women with at least

one pre-pregnancy contact with secondary mental

health-care services,3 we also evaluated associations of

this gradual implementation with the risk of adverse

obstetric and neonatal outcomes.

Research in context

Evidence before this study

There is little evidence on the effectiveness of different models

to deliver perinatal mental health care. Many countries do not

have mental health-care practitioners who are specifically

trained for delivering care during the perinatal period, and

delivery models vary widely. We searched MEDLINE from

inception to Aug 7, 2023, for evidence on the effectiveness of

specialist community perinatal mental care or equivalent

initiatives, using the following search terms (“perinatal” AND

[“mental disorders” OR “mental illness”] AND “community”

AND [“team” OR “centre” OR “center”]) without language

restrictions. We did not find any studies directly comparing

mental health or obstetric and neonatal outcomes in women

with pre-existing mental disorders who did or did not have

support from specialist perinatal mental health teams located

in the community. A UK study of 24 women with emotional

dysregulation in the perinatal period, published in 2018,

suggested that behavioural therapy delivered by a community

perinatal team could reduce stress. Another UK study of

32 women suggested that recommendations from a specialist

perinatal mental health service were followed around 80% of

the time. Qualitative research has found that women prefer the

tailored care available in specialist perinatal mental health

services compared with generic care.

Added value of this study

In England, specialist community perinatal mental health teams

were rolled out from 2016. This initiative, which is unique in the

world, aimed to improve access to specialist treatment for

women with perinatal mental health problems and improve

mental health outcomes. We found that where a community

perinatal mental health team was available, there was an

increase in access to secondary mental health care (a psychiatric

hospital admission, a crisis resolution team contact, or

community care) during pregnancy and in the first year after

birth and a decrease in the risk of an acute relapse

(a hospital admission or crisis resolution team contact) in the

first year after birth. However, we also found an increase in the

risk of stillbirth and neonatal death, and birth of a baby small for

gestational age where a community perinatal mental health

team was available, and a decrease in the risk of preterm birth.

Implications of all the available evidence

The improved access to mental health services and reduction in

acute postpartum relapse suggests that other countries could

consider developing such specialist community perinatal

mental health services. Further research on whether adverse

obstetric outcomes are associated with community perinatal

mental health teams is urgently needed. Based on our evidence,

however, specialist perinatal mental health-care practitioners

working in the community should ensure that they work closely

with other health and social care professionals to minimise the

risk that more intensive psychiatric support available in a region

negatively affects the midwifery and obstetric support that

women with severe mental disorders receive during pregnancy

and childbirth.

Articles

176

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 11 March 2024

Methods

Study design and participants

This cohort study used three consecutive versions of the

national dataset of secondary mental health care provided

by NHS England, which together included mental health-

care episodes from April 1, 2006, to March 31, 2019, linked

at patient level to Hospital Episode Statistics, which is the

administrative database of all care episodes in general

NHS hospitals,9,10 and birth notifications from the

Personal Demographic Service, which is the national

master database of all NHS patients in England

containing patient details such as name, address, date of

birth, and NHS number.11 Records of mental health-care

episodes between Dec 1, 2015, and March 31, 2016, were

not available for technical reasons.

Records from the Hospital Episode Statistics database

included patient demographics, admission dates, diag-

noses coded according to ICD-10, and procedures coded

according to OPCS Classification of Inter ventions and

Procedures version 4 (OPCS-4) codes (appendix pp 2, 4).12

Each record of a maternity episode in the Hospital

Episode Statistics database contains a set of additional

data fields, often referred to as the maternity tail, which

contain specific information, including birthweight,

gestational age, and mode of delivery.9 Birth records from

the Personal Demographic Service contained additional

information on stillbirth, gestational age, sex of the baby,

and birthweight, which was used if Hospital Episode

Statistics data were missing. Ethics approval was provided

by the NHS Health Research Authority (19/SW/0218) and

data were provided by the NHS Data Access Request

Service (DARS-NIC-376141-W5D3L-v0.9).

For this study, from Hospital Episode Statistics records

and Personal Demographic Service birth notifications, we

identified maternity episodes of all women eligible for

inclusion (aged ≥18 years) with a recorded gestation

(≥24 completed weeks) with an onset of pregnancy from

April 1, 2016, and a singleton birth up to March 31, 2018.

This inclusion period was chosen because it allowed us to

determine the mental health outcomes according to the

most recent version of the secondary mental health

services dataset for all included women (appendix p 2).

Women who had multiple births were excluded for

practical reasons; first, their number was small, and

second, including them would have made the statistical

analysis more complex because it cannot be assumed

that the outcomes of babies of a multiple birth are

independent observations. If there were multiple

maternity episodes for the same woman during the study

period, one maternity episode was selected using a

random number generator to be included in the study to

minimise selection bias and, again, to avoid the need to

use more complex statistical methods appropriate for the

analysis of non-independent outcomes.

To determine the onset of pregnancy, we subtracted the

gestational age at birth minus 2 weeks (or 38 weeks if

gestational age was not available) from the date of birth.

Women were included if they had a pre-existing mental

illness, defined as a contact with any form of secondary

mental health care, within a look-back period of 10 years

before the onset of pregnancy.8 This 10-year look-back

period was chosen on pragmatic grounds, because the

historical mental health services data were available from

April 1, 2006.

Procedures

We distinguished three levels of secondary mental health

care as a proxy for the severity of the mental disorder.

The first level (hospital admission) was an admission to a

psychiatric ward, including generic psychiatric wards,

mother–baby units, or secure wards. The second level

(crisis resolution team) was the involvement of a mental

health crisis resolution team providing intensive

treatment at home for an acute mental health crisis

otherwise needing hospital admission. The third level

(community care) was any other secondary mental

health-care contact, including day care and outpatient or

community-based care. More information can be found

in a previous paper.3

We did not use recorded diagnostic information to

distinguish the nature or severity of the women’s mental

illness because of the high rate of missingness of

diagnostic information, especially in records of the crisis

resolution team or community care. It has been widely

recognised that mental health diagnoses are often not or

incompletely recorded in administrative datasets of

mental health care.13

Information on the regional availability of community

perinatal mental health teams was collected at the level of

the Clinical Commissioning Groups.14 These groups

were NHS bodies responsible for the planning and

commissioning of health-care services for their local

area between April 1, 2013, and July 31, 2022. Initially,

211 Clinical Commissioning Groups were established

in 2013; this number decreased to 135 in 2020 because of

mergers between groups. In this study, we define the

regions according to the 207 Clinical Commissioning

Groups present in July, 2017, given that these reflect as

accurately as possible the situation for the women

included in our study. Typically, these regions cover areas

with a population of 250 000 people. We surveyed the

Clinical Commissioning Groups to determine the date of

community perinatal mental health team implementation

for each region, defined as the earliest date that at least a

dedicated psychiatrist, psychologist, and specialist nurse

were in place. We considered a community perinatal

mental health team to be available to women if the date

of implementation in their Clinical Commissioning

Group region was before the onset of pregnancy.

Outcomes

The primary mental health outcome was acute relapse

(psychiatric hospital admission or crisis resolution

team contact) in the postnatal period (the first year after

See Online for appendix

Articles

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 11 March 2024

177

birth). The secondary mental health outcome was any

secondary care contact, defined as at least one secondary

mental health-care contact during the perinatal

period (during pregnancy and the first year after

birth), also including a community mental health-care

contact.

The study also examined obstetric and neonatal

outcomes, which were stillbirth or neonatal death within

7 days of birth, preterm birth (birth before 37 completed

weeks of gestation), birth of a baby born small for

gestational age (birthweight less than the tenth centile

using the UK WHO gestationally corrected growth

charts),15 and two composite adverse outcome indicators

that capture neonatal and maternal morbidity. The

English Neonatal Adverse Outcome Indicator for

liveborn babies is derived from the presence of 15 ICD-10

diagnoses and seven OPCS-4 procedure codes present in

the babies’ Hospital Episode Statistics records before

inpatient discharge after birth (appendix p 4).16 The

English Maternal Morbidity Outcome Indicator is derived

from 17 ICD-10 diagnoses and nine OPCS-5 procedure

codes in Hospital Episode Statistics records of the

maternity episode (appendix p 4).17 For the purpose of

this study, acute psychosis was not included in the

English Maternal Morbidity Outcome Indicator because

mental illness is an inclusion criterion for this study.

Although maternal mortality data were available, we did

not include maternal mortality as an outcome in this

study because of the low statistical power.18

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was not specified in a pre-

published study protocol given that there is little

experience with the English national mental health

services datasets. However, the definitions of levels and

timing of secondary mental health care are the same as

those in a previous study by our team.3 All obstetric and

neonatal outcomes follow accepted definitions.

Hospital Episode Statistics records provided data on

maternal age, parity and previous caesarean section,

maternal ethnicity, pre-existing hypertension, pre-existing

diabetes, pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, and gestational

diabetes (appendix p 4). Socioeconomic deprivation was

derived from the quintiles of the national ranking of the

Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 of the women’s area

of residence.19 The pre-pregnancy secondary mental

health-care contacts were grouped according to the

highest level of care received and according to the timing

of the most recent contact.

Odds ratios with risk adjustment (adjORs) and their

95% CI were estimated with logistic regression. Models

were fitted with robust standard errors to account for

clustering of outcomes within regions. We estimated

three models: model 1 provided the unadjusted estimates;

model 2 included adjustment for time trends (monthly,

assuming constant relative change in the outcome in

each subsequent month); and model 3 also included risk

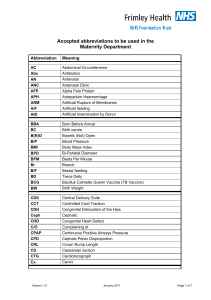

Figure 1: Trial profile

*Numbers do not add up to total excluded due to episodes excluded for more than one criterion above.

31

276 women in regions with a community

perinatal mental health team available

at onset of pregnancy

70

323 women with a mental health-care

contact before pregnancy

709

703 excluded women without secondary mental

health-care contact in 10 years before pregnancy

39

047 women in regions without a

community perinatal mental health

team available at onset of pregnancy

780

026 eligible women with one maternity

episode

Of 5105 women with multiple maternity episodes,

one episode was chosen at random

785

131 eligible maternity episodes

807

798 maternity episodes in England,

with onset of pregnancy between

April 1, 2016, and March 31, 2018

22

667 excluded maternity episodes*

1665 residing in Wales, Northern Ireland, or

unknown residential region

5646 maternal age <18 years

14

323 multiple births

1312 gestational age <24 weeks

Figure 2: Regional availability of community perinatal mental health teams in 207 regions defined according

to regions covered by NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups between 2013 and 2019

Each horizontal bar represents a region.

June, 2013 June, 2014 June, 2015 June, 2016 June, 2017 June, 2018 June, 2019

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

No community perinatal mental health

team available

Community perinatal mental health

team available

Number of community perinatal mental health teams

Calendar time (month, year)

Articles

178

www.thelancet.com/psychiatry Vol 11 March 2024

adjustment for all maternal characteristics defined above

and the level and timing of pre-pregnancy secondary

mental health-care contacts.

In response to results of the analysis of obstetric and

neonatal adverse outcomes in women with pre-existing

mental disorders, we used the same methods to

compare these outcomes according to whether a

community perinatal mental health team was available

in women without a pre-existing mental disorder

(ie, without a secondary mental health-care contact in

the 10 years before pregnancy). We also carried out two

sub-group analyses: the first included only women who

had a pre-pregnancy psychiatric hospital admission or

crisis resolution team contact, and the second included

women who had any secondary mental health-care

contact in the year immediately before the pregnancy.

Data were missing on perinatal mortality for maternal

records with missing mortality records for the babies (650

[0·9%] of 70 323), on small for gestational age for maternal

records with incomplete information on birthweight, sex

of the baby, or gestational age (531 [0·8%] of 70 323), on

preterm births for maternal records with incomplete

information on gestational age (0·2% [150 of 70 323]), and

on neonatal and maternal adverse outcomes for unlinked

maternal records (2·6% [1797 of 70 096]) or those

identified from Personal Demographic Service records

only (5·1% [3589 of 70 323]). For all regression analyses,

missing outcomes and risk factors were imputed using

chained equations generating ten datasets with estimates

across imputed datasets pooled using Rubin’s rules.20

Stata (version 17) was used for all analyses. A p value of

less than 0·05 was considered to represent statistical

significance.

Role of the funding source

The funder had no role in study design, data collection,

data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

Of 807 798 maternity episodes in England with an onset

of pregnancy after April 1, 2016, and a birth before

April 1, 2018, we identified 780 026 eligible women with a

singleton birth, of whom 70 323 (9·0%) had a pre-existing

mental disorder (figure 1).

Figure 2 shows that in April, 2016, the first month of

our cohort, a community perinatal mental health team

was available in 81 (39%) of 207 Clinical Commissioning

Group regions. The number of regions with a

community perinatal mental health team increased to

130 (63%) of 207 Clinical Commissioning Group regions

in June, 2017, just before the onset of pregnancy of

women who gave birth in March, 2018. Of 70 323 included

women, 31 276 (44·5%) gave birth where a community

perinatal mental health team was available in their

region at the onset of pregnancy and 39 047 (55·5%) gave

birth where one was not available. The characteristics of

women with and without a community perinatal mental

health team available were broadly similar (table 1), with

a lower proportion of White women in regions with a

community perinatal mental health team than in regions

without.

Of the 70 323 included women, 2862 4·1% had an

acute relapse in the postnatal period (table 2). The risk of

acute relapse varied according to regional community

perinatal mental health team availability; of 31 276 women

who gave birth in a region where a community perinatal

All women

(N=70 323)

No community perinatal

mental health team at

onset of pregnancy

(n=39 047)

Community perinatal

mental health team at

onset of pregnancy

(n=31 276)

Maternal age, years*

18–24 17 463 (24·8%) 9971 (25·5%) 7492 (24·0%)

25–34 40 031 (56·9%) 22 219 (56·9%) 17 812 (57·0%)

35–39 10 216 (14·5%) 5489 (14·1%) 4727 (15·1%)

≥40 2607 (3·7%) 1364 (3·5%) 1243 (4·0%)

Obstetric history†

Nulliparous 22 665 (32·2%) 12 749 (32·7%) 9916 (31·7%)

Multiparous, no previous

caesarean section

35 423 (50·4%) 19 558 (50·1%) 15 865 (50·7%)

Multiparous, with previous

caesarean section

8646 (12·3%) 4700 (12·0%) 3946 (12·6%)

Ethnicity‡

White 54 965 (78·2%) 31 199 (79·9%) 23 766 (76·0%)

South Asian 3244 (4·6%) 1622 (4·2%) 1622 (5·2%)

Black 1779 (2·5%) 692 (1·8%) 1087 (3·5%)

Mixed 1332 (1·9%) 661 (1·7%) 671 (2·1%)

Other stated 1160 (1·6%) 525 (1·3%) 635 (2·0%)

Socioeconomic deprivation§

Quintile 1 (least deprived) 7373 (10·5%) 4268 (10·9%) 3105 (9·9%)

Quintile 2 9765 (13·9%) 5528 (14·2%) 4237 (13·5%)

Quintile 3 12 560 (17·9%) 6820 (17·5%) 5740 (18·4%)

Quintile 4 16 522 (23·5%) 8492 (21·7%) 8030 (25·7%)

Quintile 5 (most deprived) 24 100 (34·3%) 13 937 (35·7%) 10 163 (32·5%)

Pregnancy risk factors¶

Pre-existing diabetes 1021 (1·5%) 502 (1·3%) 519 (1·7%)

Pre-existing hypertensive

conditions

488 (0·7%) 250 (0·6%) 238 (0·8%)

Gestational diabetes|| 4294 (6·4%) 2263 (6·1%) 2031 (6·8%)

Pre-eclampsia or eclampsia 1442 (2·1%) 779 (2·0%) 663 (2·1%)

Highest level of pre-pregnancy secondary mental health-care contact

Community care 53 098 (75·5%) 28 880 (74·0%) 24 218 (77·4%)

Crisis resolution team 13 832 (19·7%) 8242 (21·1%) 5590 (17·9%)

Hospital admission 3393 (4·8%) 1925 (4·9%) 1468 (4·7%)

Timing of most recent pre-pregnancy secondary mental health-care contact, years

>5 18 302 (26·0%) 10 219 (26·2%) 8083 (25·8%)

1–5 34 672 (49·3%) 19 770 (50·6%) 14 902 (47·7%)||

<1 17 349 (24·7%) 9058 (23·2%) 8291 (26·5%)

Data are n (%). *Missing n=6 (<1%). †Missing n=3589 (5·1%). ‡Missing n=7843 (11·2%). §Missing n=3 (<1%). ¶Missing

n=3589 (5·1%). ||For each characteristic, the percentages were calculated only in women with non-missing data, which

explains apparent discrepancies in percentages for gestational diabetes.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of women according to the regional availability of a community

perinatal mental health team

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

1

/

9

100%