264 Chapter 7

For most patients who are moderately to seriously

depressed, including those with persistent depressive disor-

der, the drug treatment of choice from the 1960s to the early

1990s was tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs; called this

because of their chemical structure) such as imipramine.

TCAs increase neurotransmission of the monoamines, pri-

marily norepinephrine and to a lesser extent serotonin

(Thase & Denko, 2008). The ecacy of TCAs in significantly

reducing depressive symptoms has been demonstrated in

hundreds of studies where the response of patients with

depression who were given these drugs has been compared

with the response of patients given a placebo. However,

only about 50 percent show what is considered clinically

significant improvement, and many of these patients still

have significant residual depressive symptoms. Fortunately,

about 50 percent of those who do not respond to an initial

trial of medication will show a clinically significant response

when switched to a dierent antidepressant or to a combi-

nation of medications (Hollon, Thase, & Markowitz, 2002).

Unfortunately, TCAs have unpleasant side eects for

some people (e.g., dry mouth, constipation, sexual dys-

function, and weight gain). Although these side eects

often diminish over time, they are so unpleasant to many

patients that they stop taking their medications before the

side eects go away. In addition, because these drugs are

highly toxic when taken in large doses, there is some risk in

prescribing them for suicidal patients, who might use them

for an overdose.

The side eects and toxicity of TCAs have led physi-

cians to increasingly prescribe selective serotonin reup-

take inhibitors (SSRIs) (Olfson & Marcus, 2009). SSRIs are

generally no more eective than the tricyclics; indeed some

findings suggest that TCAs are more eective than SSRIs

for severe depression. However, the SSRIs tend to have

many fewer side eects and are better tolerated by patients,

as well as being less toxic in large doses. The primary nega-

tive side eects of the SSRIs are problems with orgasm and

psychosocial risk factors for mood disorders operate across

cultures, and there is some initial evidence that factors like

rumination, hopelessness, and pessimistic attributional

style (Abela et al., 2011) are associated with risk for depres-

sion in other countries, such as China (Hong et al., 2010).

Treatments and Outcomes

7.7 Describe and distinguish between dierent

treatments for mood disorders.

Many patients with mood disorders (especially unipolar

disorders) never seek treatment. Even without formal

treatment, the great majority of individuals with mania and

depression will recover (often only temporarily) within less

than a year. However, given the enormous amount of personal

suering and lost productivity that these individuals endure,

and given the wide variety of treatments that are available

today, more and more people who experience these disorders

are seeking treatment. There was a rapid increase in the

treatment of depression from 1987 to 1997, and there has been

a more modest increase since 1998 (Marcus & Olfson, 2010).

Interestingly, between 1998 and 2007, there was a decline in

the reported use of psychotherapy, although the use of

antidepressant medication remained relatively stable. These

changes are happening in an era in which there is greatly

increased public awareness of the availability of eective

treatments and during a time in which significantly less

stigma is associated with experiencing a mood disorder.

Nevertheless, only about 40 percent of people with mood

disorders receive minimally adequate treatment, with the

other 60 percent receiving no treatment or inadequate care

(Wang, Lane, et al., 2005). Fortunately, the probability of

receiving treatment is somewhat higher for people with

severe unipolar depression and with bipolar disorder than for

those with less severe depression (Kessler et al., 2007).

Pharmacotherapy

Antidepressant, mood-stabilizing, and antipsychotic drugs

are all used in the treatment of unipolar and bipolar disor-

ders (see Chapter 16 for further information about these

medications). The first category of antidepressant medica-

tions—developed in the 1950s—is the monoamine oxidase

inhibitors (MAOIs) because they inhibit the action of mono-

amine oxidase, the enzyme responsible for the breakdown

of norepinephrine and serotonin once released. The MAOIs

can be as eective in treating depression as other categories

of medications, but they have potentially dangerous (even

potentially fatal) side eects if certain foods rich in the amino

acid tyramine are consumed (e.g., red wine, beer, aged

cheese, salami). Thus, they are not used very often today

unless other classes of medication have failed. Depression

with atypical features is the one subtype of depression that

seems to respond preferentially to the MAOIs. Illustration of serotonin.

Timonina/Shutterstock

M07_BUTC4568_18_GE_C07.indd 264 24/09/2020 14:15

Mood Disorders and Suicide 265

medication because about 50 percent of those who do not

respond to the first drug prescribed do respond to a second

one. Also, discontinuing the drugs when symptoms have

remitted may result in relapse. Recall that the natural

course of an untreated depressive episode is typically 6 to 9

months. Thus, when depressed patients take drugs for 3 to

4 months and then stop because they are feeling better, they

are likely to relapse because the underlying depressive epi-

sode is actually still present, and only its symptomatic

expression has been suppressed (Gitlin, 2002; Hollon,

Thase, & Markowitz, 2002; Hollon et al., 2006). Because

depression is often a recurrent disorder, physicians have

increasingly recommended that patients continue for very

long periods of time on the drugs (ideally at the same dose)

in order to prevent recurrence (Nutt, 2010). Thus, these

medications can often be eective in prevention, as well as

treatment, for patients subject to recurrent episodes (Hollon

et al., 2006; Thase & Denko, 2008). Nevertheless, approxi-

mately 25 percent of patients continuing to receive medica-

tion during the maintenance phase of treatment show

recurrence of MDD (Solomon et al., 2005). Patients showing

residual symptoms are most likely to relapse, indicating the

importance of trying to treat the patient to full remission of

symptoms (Keller, 2004; Thase & Denko, 2008).

LITHIUM AND OTHER MOOD-STABILIZING DRUGS

Lithium therapy has now become widely used as a mood

stabilizer in the treatment of both depressive and manic

lowered interest in sexual activity, although insomnia,

increased physical agitation, and gastrointestinal distress

also occur in some patients (Thase, 2009b).

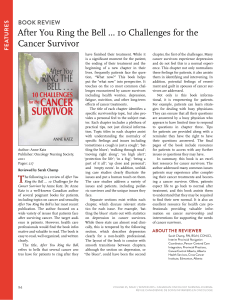

SSRIs are used not only to treat severe depression but

also to treat people with mild depressive symptoms (Git-

lin, 2002). Importantly, recent research has shown that anti-

depressant medication is superior to placebo only for

patients with very severe depressive symptoms, with neg-

ligible treatment eects observed for those with less severe

symptoms (Fournier et al., 2010; see Figure 7.9).

In the past decade, several new atypical antidepres-

sants (neither tricyclics nor SSRIs) have also become

increasingly popular, each with its own advantages

( Marcus & Olfson, 2010). For example, bupropion

( Wellbutrin) does not have as many side eects (especially

sexual side eects) as the SSRIs and, because of its activat-

ing eects, is particularly good for depression involving

significant weight gain, loss of energy, and oversleeping. In

addition, venlafaxine (Eexor) seems superior to the SSRIs

in the treatment of severe or chronic depression, although

the profile of side eects is similar to that for the SSRIs.

Several other atypical antidepressants have also been

shown to be eective (see Chapter 16).

THE COURSE OF TREATMENT WITH ANTIDEPRESSANT

DRUGS Antidepressant drugs usually require at least 3 to

5 weeks to take eect. Generally, if there are no signs of

improvement after about 6 weeks, physicians try a new

HRSD change

0

810121416182022242628303234363840

4

8

12

16

20

24

28

32

HRSD scores at intake

Observed placebo change

Observed ADM change

Estimated placebo change

Estimated ADM change

Figure 7.9 Eectiveness of Antidepressants Based on Severity of Depression

This figure shows the amount of change in depressive symptoms, as measured by the Hamilton Rating

Scale for Depression (HRSD), from treatment intake to the end of treatment for those receiving antidepres-

sant medication (ADM; dark circles) relative to placebo (light circles). The size of the circle represents the

number of data points that contributed to that mean. The two lines represent the estimated change in

depressive symptoms. Note that the circles (and lines) are overlapping for those with low and moderate

depressive symptoms at intake (the left half of the figure), and a dierence between ADM and placebo

only emerges for those with high depressive symptoms at intake (the right half of the figure). The take-

home message: Antidepressants appear to be most eective for severe depression, but are no more

eective than placebo for mild or moderate depression.

(Based on Fournier J. C., DeRubeis R. J., Hollon S. D., Dimidjian S., Amsterdam J. D., Shelton R. C., and Fawcett J.

(2010). Antidepressant drug eects and depression severity: A patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA, 303, 47-53.)

M07_BUTC4568_18_GE_C07.indd 265 24/09/2020 14:15

266 Chapter 7

signs of psychosis (hallucinations and delusions) may also

receive treatments with antipsychotic medications (see

Chapters 13 and 16) in conjunction with their antidepres-

sant or mood-stabilizing drugs (Keck & McElroy, 2002;

Rothschild et al., 2004).

Alternative Biological Treatments

In addition to the use of pharmacotherapy, there are sev-

eral other biologically oriented approaches to the treat-

ment of mood disorders. These approaches have been the

subject of empirical study in recent years, and they appear

to be promising treatment options.

ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY Because antidepres-

sants often take 3 to 4 weeks to produce significant

improvement, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is often

used with patients who are severely depressed (especially

among the elderly) and who may present an immediate

and serious suicidal risk, including those with psychotic or

melancholic features (Goodwin & Jamison, 2007). It is also

used in patients who cannot take antidepressant medica-

tions or who are otherwise resistant to medications

(Heijnen et al., 2010; Mathew et al., 2005). When selection

criteria for this form of treatment are carefully observed, a

complete remission of symptoms occurs for many patients

after about 6 to 12 treatments (with treatments adminis-

tered about every other day). This means that a majority of

patients with severe depression can be vastly better in 3 to

5 weeks (George et al., 2013). The treatments, which induce

seizures, are delivered under general anesthesia and with

muscle relaxants. The most common immediate side eect

is confusion, although there is some evidence for lasting

adverse eects on cognition, such as amnesia and slowed

response time (Sackeim et al., 2007). Maintenance dosages

of an antidepressant and a mood-stabilizing drug such as

lithium are then ordinarily used to maintain the treatment

gains achieved until the depression has run its course

(Mathew et al., 2005; Sackeim et al., 2009). ECT is also very

useful in the treatment of manic episodes; reviews of the

evidence suggest that it is associated with remission or

marked improvement in 80 percent of patients with mania

(Gitlin, 1996; Goodwin & Jamison, 2007). Maintenance on

mood-stabilizing drugs following ECT is usually required

to prevent relapse.

TRANSCRANIAL MAGNETIC STIMULATION Although

transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has been available

as an alternative biological treatment for some time now,

only in the past decade has it begun to receive significant

attention. TMS is a noninvasive technique allowing focal

stimulation of the brain in patients who are awake. Brief but

intense pulsating magnetic fields that induce electrical

activity in certain parts of the cortex are delivered (Goodwin

& Jamison, 2007; Janicak et al., 2005). The procedure is

episodes of bipolar disorder. The term mood stabilizer is

often used to describe lithium and related drugs because

they have both antimanic and antidepressant eects—that

is, they exert mood-stabilizing eects in either direction.

Lithium has been more widely studied as a treatment of

manic episodes than of depressive episodes, and estimates

are that about three-quarters of those in a manic episode

show at least partial improvement. In the treatment of

bipolar depression, lithium may be no more eective than

traditional antidepressants (study results are inconsistent),

but about three-quarters show at least partial improve-

ment (Keck & McElroy, 2007). However, treatment with

antidepressants is associated with significant risk of pre-

cipitating manic episodes or rapid cycling, although the

risk of this happening is reduced if the person also takes

lithium (Keck & McElroy, 2007; Thase & Denko, 2008).

Lithium is often effective in preventing cycling

between manic and depressive episodes (although not nec-

essarily for patients with rapid cycling), and patients with

bipolar disorder frequently are maintained on lithium

therapy over long time periods, even when not manic or

depressed, simply to prevent new episodes. Unfortunately,

several large studies recently have found that only about

one-third of patients maintained on lithium remained free

of an episode over a 5-year follow-up period. Neverthe-

less, patients on lithium maintenance do have fewer epi-

sodes than patients who discontinue their medication

(Keck & McElroy, 2007).

Lithium therapy can have some unpleasant side eects

such as lethargy, cognitive slowing, weight gain, decreased

motor coordination, and gastrointestinal diculties. Long-

term use of lithium is occasionally associated with kidney

malfunction and sometimes permanent kidney damage,

although end-stage renal disease seems to be a very rare

consequence of long-term lithium treatment (Goodwin &

Jamison, 2007; Tredget et al., 2010). Not surprisingly, these

side eects, combined with the fact that many patients with

bipolar disorder seem to miss the highs and the abundance

of energy associated with their hypomanic and manic epi-

sodes, sometimes cause patients to refuse the drug.

In the past several decades, evidence has emerged for

the usefulness of another category of drugs known as the

anticonvulsants (e.g., carbamazepine, divalproex, and val-

proate) in the treatment of bipolar disorder. These drugs

are often eective in patients who do not respond well to

lithium or who develop unacceptable side eects from it,

and they may also be given in combination with lithium.

However, a number of studies have indicated that risk for

attempted and completed suicide was nearly two to three

times higher for patients on anticonvulsant medications

than for those on lithium (Goodwin et al., 2003; Thase &

Denko, 2008), suggesting one major advantage of giving

lithium to patients who can tolerate its side eects. Both

people with bipolar or unipolar depression who show

M07_BUTC4568_18_GE_C07.indd 266 24/09/2020 14:15

Mood Disorders and Suicide 267

BRIGHT LIGHT THERAPY In the past decade an alterna-

tive nonpharmacological biological method has received

increasing attention: bright light therapy (see Pail et al.,

2011, for a review). This was originally used in the treat-

ment of seasonal aective disorder, but it has now been

shown to be eective in nonseasonal depressions as well

(Golden et al., 2005; Lieverse et al., 2011).

Psychotherapy

Several forms of specialized psychotherapy, developed

since the 1970s, have proved eective in the treatment of

unipolar depression, and the magnitude of improvement

of the best of these is approximately equivalent to that

observed with medications. Considerable evidence also

suggests that these same specialized forms of psychother-

apy for depression, alone or in combination with drugs,

significantly decrease the likelihood of relapse within a

2-year follow-up period (Hollon & Dimidjian, 2009; Hollon

et al., 2005). Other specialized treatments have been devel-

oped to address the problems of people (and their families)

with bipolar disorder.

COGNITIVE-BEHAVIORAL THERAPY One of the two

best-known psychotherapies for unipolar depression with

documented eectiveness is cognitive-behavioral therapy

(CBT) (also known as cognitive therapy), originally devel-

oped by Beck and colleagues (Beck et al., 1979; Clark, Beck,

& Alford, 1999). It is a relatively brief form of treatment

(usually 10 to 20 sessions) that focuses on here-and-now

problems rather than on the more remote causal issues that

psychodynamic psychotherapy often addresses. For exam-

ple, cognitive therapy consists of highly structured, sys-

tematic attempts to teach people with unipolar depression

to evaluate systematically their dysfunctional beliefs and

negative automatic thoughts. They are also taught to iden-

tify and correct their biases or distortions in information

processing and to uncover and challenge their underlying

depressogenic assumptions and beliefs. Cognitive therapy

relies heavily on an empirical approach in that patients are

taught to treat their beliefs as hypotheses that can be tested

through the use of behavioral experiments.

One example of challenging a negative automatic

thought through a behavioral experiment can be seen in

the following interchange between a cognitive therapist

and a patient with depression.

Therapy Session: “My Husband Doesn’t Love Me

Anymore”

PATIENT: My husband doesn’t love me anymore.

THERAPIST: That must be a very distressing thought. What makes you

think that he doesn’t love you?

PATIENT: Well, when he comes home in the evening, he never wants

to talk to me. He just wants to sit and watch TV. Then he goes

straight o to bed.

THERAPIST: OK. Now, is there any evidence, anything he does, that

goes against the idea that he doesn’t love you?

PATIENT: I can’t think of any. Well, no, wait a minute. Actually it was my

birthday a couple of weeks ago, and he gave me a watch which

is really lovely. I’d seen them advertised and mentioned I liked it,

and he took notice and went and got me one.

THERAPIST: Right. Now how does that fit with the idea that he doesn’t

love you?

PATIENT: Well, I suppose it doesn’t really, does it? But then why is he

like that in the evening?

THERAPIST: I suppose him not loving you any more is one possible

reason. Are there any other possible reasons?

painless, and thousands of stimulations are delivered in

each treatment session. Treatment usually occurs 5 days a

week for 2 to 6 weeks. Many studies have shown it to be

quite eective—indeed in some studies quite comparable

to unilateral ECT and antidepressant medications (George

& Post, 2011; Janicak et al., 2005; Schulze-Rauschenbach et

al., 2005). In particular, research suggests that TMS is a

promising approach for the treatment of unipolar depres-

sion in patients who are moderately resistant to other treat-

ments (George & Post, 2011). Moreover, TMS has

advantages over ECT in that cognitive performance and

memory are not aected adversely and sometimes even

improve, as opposed to ECT, where memory-recall deficits

are common (George et al., 2013). Finally, TMS appears

to be safe for use with children and adolescents, with

only low rates of mild and transient side eects such as

headaches (12 percent) and scalp discomfort (3 percent)

(Krishnan et al., 2015).

DEEP BRAIN STIMULATION In recent years, deep brain

stimulation has been explored as a treatment approach for

individuals with refractory depression who have not

responded to other treatment approaches, such as medica-

tion, psychotherapy, and ECT. Deep brain stimulation

involves implanting an electrode in the brain and then stimu-

lating that area with an electric current (Mayberg et al., 2005).

Although more research on deep brain stimulation is needed,

initial results suggest that it may have potential for treatment

of unrelenting depression (see Chapter 16 for more details).

Neuroimaging has played a pivotal role in identifying some deep brain

stimulation targets.

Triff/Shutterstock

M07_BUTC4568_18_GE_C07.indd 267 24/09/2020 14:15

268 Chapter 7

Teasdale, 2004). The logic of this treatment is based on find-

ings that people with recurrent depression are likely to

have negative thinking patterns activated when they are

simply in a depressed mood. Perhaps rather than trying to

alter the content of their negative thinking as in traditional

cognitive therapy, it might be more useful to change the

way in which these people relate to their thoughts, feelings,

and bodily sensations. This group treatment involves train-

ing in mindfulness meditation techniques aimed at devel-

oping patients’ awareness of their unwanted thoughts,

feelings, and sensations so that they no longer automati-

cally try to avoid them but rather learn to accept them for

what they are—simply thoughts occurring in the moment

rather than a reflection of reality. A recent meta-analysis of

findings from six randomized controlled trials of individu-

als in remission from depression suggests that mindful-

ness-based cognitive therapy is an eective treatment for

reducing risk of relapse in those with a history of three or

more prior depressive episodes who have been treated

with antidepressant medication (Piet & Hougaard, 2011).

Although the vast majority of research on CBT has

focused on unipolar depression, recently there have been

indications that a modified form of CBT may be quite useful,

in combination with medication, in the treatment of bipolar

disorder as well (Lam et al., 2003, 2005; Miklowitz, 2009).

There is also preliminary evidence that mindfulness-based

PATIENT: Well, he has been working very hard lately. I mean, he’s late

home most nights, and he had to go in to the oce at the

weekend. So I suppose it could be that.

THERAPIST: It could, couldn’t it? How could you find out if that’s it?

PATIENT: Well, I could say I’ve noticed how tired he looks and ask him

how he’s feeling and how the work’s going. I haven’t done that.

I’ve just been getting annoyed because he doesn’t pay any

attention to me.

THERAPIST: That sounds like an excellent idea. How would you like to

make that a homework task for this week?

(From Fennell, M. J. V. (1989). Depression. In K. Hawton, P. M. Salkovskis, J. Kirk,

& D. M. Clark (Eds.), Cognitive behaviour therapy for psychiatric problems: A

practical guide. Oxford University Press.)

The usefulness of cognitive therapy has been amply

documented in dozens of studies, including several stud-

ies on hospital patients with unipolar depression and on

patients diagnosed with depression with melancholic fea-

tures (Craighead et al., 2007; Hollon, Haman, & Brown,

2002; Hollon et al., 2006). When compared with pharmaco-

therapy, it is at least as eective when delivered by well-

trained cognitive therapists. It also seems to have a special

advantage in preventing relapse, similar to that obtained

by staying on medication (Hollon, 2011; Hollon & Ponniah,

2010). Moreover, evidence is beginning to accumulate that

it can prevent recurrence several years following the epi-

sode when the treatment occurred (Craighead et al., 2007;

Hollon & Dimidjian, 2009). Perhaps not surprisingly, some

recent interesting brain-imaging studies have

shown that the biological changes in certain brain

areas that occur following effective treatment

with cognitive therapy versus medications are

somewhat dierent, suggesting that the mecha-

nisms through which they work are also dierent

(Clark & Beck, 2010; Hollon & Dimidjian, 2009).

One possibility is that medications may target the

limbic system, whereas cognitive therapy may

have greater eects on cortical functions.

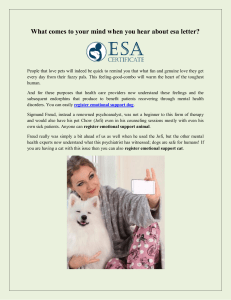

CBT and medications have been found to be

equally eective in the treatment of severe depres-

sion (DeRubeis et al., 1999; Hollon et al., 2006). For

example, one important two-site study of moderate

to severe depression found that 58 percent

responded to either cognitive therapy or medica-

tion (DeRubeis et al., 2005). However, by the end of

the 2-year follow-up, when all cognitive therapy

and medications had been discontinued for 1 year,

only 25 percent of patients treated with cognitive

therapy had had a relapse versus 50 percent in the

medication group (Hollon & Dimidjian, 2009;

Hollon et al., 2005). This is illustrated in Figure 7.10.

Another variant on cognitive therapy, called

mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, has been devel-

oped in recent years to be used with people with

highly recurrent depression (Segal et al., 2002,;

Prior CT Group (n = 20)

Prior ADM Group (n = 14)

161412 2018 22 24

Percentage of patients with no recurrence

Time following the end of continuation (months)

0

120

100

80

60

40

20

Figure 7.10

Survival curve illustrating how many months following the end of treatment it

took patients from the two groups before they had another episode of depres-

sion (recurrence). One group had previously received cognitive therapy (CT) and

the other group had received antidepressant medication (ADM).

(Based on Hollon, et al. (2005, April). Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy

vs. medications in moderate to severe depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiat., 62(4), 417–26.

American Medical Association.)

M07_BUTC4568_18_GE_C07.indd 268 24/09/2020 14:15

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

1

/

15

100%