Pediatric Pneumonia: Diagnosis, Investigation & Treatment Guide

Telechargé par

tyamoune

Paediatric pneumonia: a

guide to diagnosis,

investigation and

treatment

Ellen Crame

Michael D Shields

Patrick McCrossan

Abstract

Community-acquired pneumonia remains the leading cause of death

in children under 5 years of age throughout the world. Community ac-

quired pneumonia can include bacterial, viral and fungal causes but it

is very difficult to clinically differentiate between them. Whilst viral

pathogens have been identified as the most common aetiology, bac-

terial infections are considered the more likely to cause severe dis-

ease. It is important that the clinician has the ability to safely

differentiate between those that may require further treatment or

admission to hospital and those that can be managed at home. With

a wide range of presenting symptoms and potential complications,

pneumonia poses a challenge for paediatricians. This article aims to

guide physicians in the management, diagnosis and follow up of chil-

dren with suspected pneumonia, as well as discuss future develop-

ments in this field.

Keywords chest infection; childhood; lower respiratory tract infec-

tion; paediatric; pneumonia

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia remains the leading cause of

death in children between the ages of 28 days and 5 years.

1

Pneumonia affects children globally, although is most prevalent

with highest mortality in sub-Saharan Africa and lower socio-

economic regions where vaccines are less accessible.

2

Vaccina-

tion is a cost-effective strategy in preventing death from pneu-

monia

2

and the introduction of the primary childhood vaccine

program in the United Kingdom (UK) significantly reduced the

incidence of pneumonia.

3

Pneumonia has a marked seasonal pattern, with a much

higher prevalence throughout the winter due to the preponder-

ance of infections such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV),

influenza and pneumococcus.

1

With so many children affected,

pneumonia presents a significant risk to child health and a

burden on healthcare resources. With a wide range of presenting

symptoms and potential complications, pneumonia poses a

challenge for paediatricians. This article aims to guide physicians

in the management, diagnosis and follow up of children with

suspected pneumonia, as well as discuss future developments in

this field.

What is pneumonia?

Currently, no single definition of pneumonia exists that is uni-

versally accepted. Pneumonia is essentially an infection in the

lower respiratory tract (bronchi to alveoli) in which the inflam-

matory process leads to accumulation of fluid in the airspaces

which interferes with gas exchange, leading to the typical

symptoms of tachypnoea, increased work of breathing, hypoxia

and cough.

Traditional pathological studies reported that there are four

pathological stages of pneumonia:

1. Congestion: Over the first 24 hours there is alveolar oedema

and vascular congestion.

2. Red hepatisation: In days 2e4, exudate, containing red blood

cells, neutrophils and fibrin fill the airspaces making them

more solid.

3. Grey hepatisation: In days 5e7, the red cells in the exudate are

beginning to break down.

4. Resolution: From day 8 up to 3 weeks the exudate is broken

down by enzymes, digested by macrophages or coughed up as

sputum.

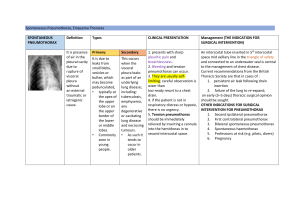

Pneumonia can be classified based on the radiographic

appearance although this does not necessarily correlate with

severity or aetiology of the disease. Bronchopneumonia (see

Figure 1) appears as bilateral multifocal consolidative patches.

This can progress to lobar pneumonia (see Figure 2) where there

is a large and continuous consolidation of an entire lobe within

the lung. Round pneumonia (see Figure 3) is a phenomenon of

children whereby the radiograph depicts a round, well-

circumscribed opacity most commonly in the lower lobes.

Round pneumonia is thought to be due to underdevelopment of

the pores of Kohn and canals of Lambert, which in adults, allows

dissemination of infection throughout a lobe.

What causes pneumonia?

Community-acquired pneumonia can have bacterial, viral and

fungal causes (see Table 1). Viral pathogens have been identified

as the most common aetiology.

4

These include Respiratory

Syncytial Virus (RSV), Rhinovirus, Influenza, Parainfluenza,

Human Metapneumovirus (hMPV) and Adenovirus. Cytomega-

lovirus (CMV) related pneumonia also needs to be considered in

immunosuppressed patients, particularly those with underlying

HIV infection.

Although viral infections are the more common cause, bac-

terial infections are considered the more likely to cause severe

disease and are responsible for up to 64% of pneumonia-related

deaths.

5

Globally, Streptococcus pnuemoniae and Haemophilus

Ellen Crame MB ChB MRCPCH Paediatric Registrar, Royal Belfast

Hospital for Sick Children (Belfast HSC Trust), UK. Conflicts of

interest: none declared.

Michael D Shields MB ChB MD FRCPCH Professor of Child Health,

Queen’s University Belfast and Consultant Paediatrician, Royal

Belfast Hospital for Sick Children (Belfast HSC Trust), UK. Conflicts

of interest: none declared.

Patrick McCrossan MB BCh BAO MRCPCH MD MSc Academic Clinical

Lecturer, Queen’s University Belfast and Paediatric Registrar, Royal

Belfast Hospital for Sick Children (Belfast HSC Trust), UK. Conflicts

of interest: none declared.

PERSONAL PRACTICE

PAEDIATRICS AND CHILD HEALTH 31:6 250 Ó2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

influenzae remain the most common pathogens. In areas with

good pneumococcal conjugate (PCV) and H. influeznae B (Hib)

vaccine coverage, Staphylococcus aureus and H. influenzae non-B

type are the most prolific. Atypical pneumonias such as Myco-

plasma and Chlamydia account for 27e36% of children admitted

with bacterial pneumonia admitted to hospital

5

(Atypical pneu-

monia is caused by organisms which are difficult to detect on

traditional gram stain and culture methods). This may be due to

the higher rates of hospital admission in the atypical subtypes

due to failure of first line antibiotics. In areas where there are

higher rates of tuberculosis (TB), or travel and immigrations

from these areas, TB needs to be considered as a potential cause.

Fungal causes are particularly important to keep in mind when

assessing immunosuppressed patients, Pneumocystis (PCP)

being the most common cause in HIV infected children.

How does pneumonia in children present?

The symptoms of pneumonia are often nonspecific and can be

very wide ranging, making it a potentially challenging condition

to diagnose. Symptoms also vary with age, although the most

accepted common presenting features of pneumonia in all age

groups include fever, cough, rhinorrhoea, dyspnoea, malaise and

lethargy. Symptoms in infants can include reduced feeding,

grunting breathing and apnoea.

1

Conversely, in older children

more common symptoms are breathlessness, pleuritic chest pain,

abdominal pain and headache.

Clinical examination signs include decreased breath sounds

and focal crepitations on auscultation. These are very sensitive

markers of disease but have a low specificity and are at times

subjective depending on the examiner. Tachypnoea and hypo-

xaemia also have high sensitivity for predicting the presence of a

pneumonia in children of all ages and respiratory rate in partic-

ular can be a very valuable sign in guiding diagnosis and raising

suspicion of disease.

3

Conversely, children with wheeze and low-

grade fever typically do not have pneumonia.

3

Where the diag-

nosis of pneumonia is being considered it is very important to

carefully percuss the chest. Whilst a dull note alone will be often

heard (or felt) in a child with a localised pneumonia, a stony dull

note should alert the clinician to the possibility of a pleural

effusion or empyema.

As seen in Table 1, pneumonia can be caused by bacteria,

fungus and viruses and it is very difficult to clinically differen-

tiate between the underlying causes. However, a higher index of

suspicion for bacterial infection should be considered in children

presenting with persistent fever, breathlessness and increased

work of breathing in the absence of wheeze.

3

Investigations

There are no investigations recommended for children with

pneumonia who can be safely managed in the community. For

those requiring secondary care assessment and admission to

hospital, the physician may consider the following:

Microbiological tests

Sputum gram stain and culture is a useful test to determine the

underlying bacterial causative organism. However, sputum

samples are notoriously difficult to obtain in younger children

and take several days to culture. They are particularly useful for

the child who is severely unwell or not responding to treatment,

in order to target antimicrobial therapy. Also, if admitted to the

Intensive Care Unit, a bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) sample is

readily attainable via their endotracheal tube.

Nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) can be sent for viral poly-

merase chain reaction (PCR). NPA are sensitive for detecting the

presence of viruses but are not adequate for determining bacte-

rial causes as the presence of normal nasal bacterial flora affects

the interpretation.

Rapid detection of the capsular polysaccharide (CPS) antigen

of Streptococcus pneumoniae from urine samples has shown

some promise with a high sensitivity and negative predictive

value for detecting pneumococcal infection. However, its low

specificity undermines its clinical utility.

6

Imaging

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines state that,

‘children with symptoms and signs suggesting pneumonia

who are not admitted to hospital should not routinely have a

chest X-ray’.

3

Chest radiographs should not be considered a

routine investigation for children with suspected pneumonia,

nor is it necessary to make the diagnosis. Reviewing the

literature on studies of chest x-rays, there can be no

Figure 1 Bronchopneumonia.

Figure 2 Lobar pneumonia.

PERSONAL PRACTICE

PAEDIATRICS AND CHILD HEALTH 31:6 251 Ó2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

significant links made between radiological findings and

aetiology.

3

The finding on chest x-rays also play no signifi-

cant role in guiding the management of the pneumonia when

the decision whether to treat with antibiotics is based on

clinical findings and the response of symptoms to treatment.

7

In addition, chest x-rays can be challenging to interpret, and

findings are often subjective. The interpretation of x-rays is

limited by the quality of the film and dependant on the

expertise of the reader.

8

Many studies have demonstrated

significant variability and discrepancy between chest X-ray

findings when interpreted by both radiologists and clinicians.

8

However, chest x-rays do play a role when complications of

pneumonia are suspected. Chest X-ray should be considered

where symptoms are persistent and where there is an inad-

equate response to treatment within 72 hours.

8

Blood tests

Collating the data from multiple studies, the BTS concluded that,

‘acute phase reactants are not of clinical utility in distinguishing

viral from bacterial infections and should not routinely be

tested’.

5

Both viral and bacterial infections can cause a rise in C

Reactive Protein (CRP) and as a result the CRP should not in-

fluence the decision to treat for bacterial illness. However, CRP

does play a role when complications are suspected, and a rising

CRP may be an indication for more complex disease not

improving with existing treatment. Neither a raised white cell

count (WCC) nor erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) has been

proven to differentiate between viral and bacterial aetiologies.

9

Procalcitonin (PCT) is released as part of the proinflammatory

response of the innate immune system. It reaches detectable

leaves at a faster rate than other inflammatory markers such as

CRP and is not raised by viruses or collagen vascular diseases. A

study by Baumann et al. suggests the elevated PCT is a good

marker for pneumococcal infection and as a result, elevated PCT

could be used to guide the treatment with antibiotics in children

with a suspected diagnosis of pneumonia.

10

Management

The first step in managing children with pneumonia is deciding

whether or not they can be managed safely in the community, or

whether they need referring to a hospital. A thorough assessment

of disease severity is needed on first presentation, with the

premise that previously well children with mild disease are best

managed at home. An assessment of severity will also influence

the decision to investigate and initiate treatment, as well as guide

the duration of treatment and level of medical and nursing care

required in the hospital setting.

The initial assessment of a child presenting with infective

symptoms will normally take place in the primary care or

emergency department setting. Doctors will assess children

based on their clinical presentation but will also need to consider

associated risk factors. Underlying health conditions and the

social background of the child can impact on the ability for the

condition to be well managed in the community. Children with

complex needs and chronic underlying lung conditions may be

more vulnerable to severe disease and may have a lower respi-

ratory reserve. As a result, there is a lower threshold for initiation

of antibiotic treatment and admission to hospital.

Unlike the CURB 65 score in adults, there is no reliable

assessment tool for scoring severity of disease in children.

3

As a

result, clinical markers of severity (see Table 2) remain the gold

standard for assessing children that need hospital care. One of

the most important measures to guide the need for admission to

hospital is oxygen saturations, with hypoxaemia being a sensi-

tive indicator of disease severity and prognosis.

11

Also, tachyp-

noea correlates with hypoxaemia and so the respiratory rate

requires careful assessment.

The severely unwell child may require admission to the Pae-

diatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU). The two main scenarios where

PICU is indicated are when the pneumonia is severe enough to

cause respiratory failure, requiring ventilatory support, or when

the pneumonia is complicated by septicaemia. The diagnosis of

respiratory failure is made following blood gas analysis. In chil-

dren outside of the PICU setting, capillary or venous blood gases

are most commonly used as arterial sampling is painful and very

challenging in smaller children who do not have an arterial

catheter. Respiratory failure would be indicated by low PaO

2

readings and a high PaCO

2

which may indicate the need for

respiratory support and thus referral to a high dependency unit.

Septicaemia may present as tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypo-

xaemia, signs of shock or recurrent apnoea with irregular

breathing patterns.

Treatment

For children that do not warrant hospital admission, robust

safety netting advice should be implemented to ensure that

parents are aware of the signs of worsening disease, as discussed

above.

The mainstay of hospital treatment is supportive manage-

ment. This may involve oxygen therapy if pulse oximetry reveals

oxygen saturations lower than 92%.

3

Intravenous fluids may be

indicated when the child is struggling to maintain oral input due

to breathlessness and fatigue, to prevent dehydration. Nasogas-

tric tubes, although useful for providing hydration in many sce-

narios, should be avoided where possible in smaller children as

Figure 3 Round pneumonia.

20

Source: reproduced from reference 20

with permission of Springer-Verlag 2010.

PERSONAL PRACTICE

PAEDIATRICS AND CHILD HEALTH 31:6 252 Ó2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

they can cause further breathing compromise by obstructing the

smaller nasal passages.

3

With the use of intravenous fluids

comes the risk of electrolyte imbalance, made more pronounced

in pneumonia by the potential development of the syndrome of

inappropriate anti-diuretic hormone (SIADH). Therefore, elec-

trolyte and sodium monitoring are required to prevent hypona-

traemia in instances where prolonged intravenous fluids are

administered.

Chest physiotherapy is not felt to be beneficial in children

with uncomplicated pneumonia. Chest physiotherapy may

potentially prolong fever duration and exacerbate breathing dif-

ficulties

12

and is not recommended as part of management for

children with pneumonia by the British Thoracic Society. Chest

physiotherapy, along with the use of mucolytic agents, continues

to play a role in airway clearance in some children with complex

needs who may struggle to independently clear secretions. In

addition, where acute airway collapse is secondary to mucoid

secretions causing plugging in the bronchi, assisted airway

clearance will again be an important part of the management

strategy.

The world health organisation (WHO) defines pneumonia as,

‘the presence of either fast breathing or lower chest wall in-

drawing where the child’s chest moves in or retracts during

inhalation.

1

’ The WHO states that due to the high mortality and

morbidity rates worldwide, a child with suspected pneumonia

should be treated with antibiotic therapy. This WHO definition of

pneumonia was developed in order to be easily implemented by

primary health care workers in the developing world to guide their

use of prescribing antibiotics and thus prevent the serious

sequelae of what is the most common cause of serious illness and

death in young children worldwide. This was successful and

resulted in a significant reduction in all-cause mortality for chil-

dren. However, such high sensitivity comes at the cost of speci-

ficity, failing to distinguish between bacterial and viral causes.

Indeed, research into use of the WHO guidelines in low-income

countries has identified overdiagnosis of pneumonia in cases of

wheezing, with consequent underdiagnosis of asthma, leading to

significant respiratory morbidity and, perhaps, even mortality.

13

As previously discussed, viral aetiology is more frequent than

bacterial and there is no evidence to support that either chest X-

ray findings or inflammatory markers can reliably distinguish

between the two. There has been much consideration given to

the extensive use of antibiotics and the economic and health

burden that results.

14

BTS guidelines state that in a child under

two years with mild symptoms, the cause is most likely to be

viral in nature.

3

Where the child appears acutely unwell, im-

mediate administration of antibiotics is recommended, however

it may be reasonable to carefully consider the use of antibiotics in

mild disease.

14

If deciding upon prescribing antibiotics, Amoxicillin is recom-

mended as first line treatment of lower respiratory tract infection,

as it has effective coverage against the most common pathogens in

children.

3

BTS guidance states that oral amoxicillin should be used

in the first instance though there may be local microbiological

guidelines in place depending on the prevalence of antibiotic

Common pathogens causing pneumonia in children

Age Bacteria Viruses

<20 days E. coli, Group B Streptococcus,Listeria Herpes simplex virus, Cytomegalovirus

3 weekse3 months Chlamydia trachomatis,Streptococcus

pneumoniae,Pertussis,Haemophilus

influenzae,Staphylococcus aureus,Moraxella

catarrhalis

Adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus,

parainfluenza, influenza

4 monthse5 years Streptococcus pneumoniae,Mycoplasma,

Haemophilus influenzae,Staphylococcus

aureus

Adenovirus, rhinovirus, influenza,

parainfluenza, varicella zoster, respiratory

syncytial virus

>5 years Streptococcus pneumoniae,Mycoplasma,

Staphylococcus aureus,Tuberculosis

Adenovirus, Epstein Barr virus, influenza,

rhinovirus

Table 1

Clinical indicators of severity in childhood pneumonia

5

Mild/moderate Severe

Infants Temp <38.5C

RR <50 breaths/minute

Mild recession

Taking full feeds

Temp >38.5C

RR >70 breaths/minute

Moderate/severe recession

Cyanosis

Intermittent apnoea

Poor feeding

Capillary refill time

>2 second

Tachycardia

Older children Temp <38.5C

RR <50 breaths/minute

Mild breathlessness

No vomiting

Temp >38.5C

RR >50 breaths/minute

Severe difficulty in

breathing

Nasal flaring

Grunting

Cyanosis

Signs of dehydration

Tachycardia

Capillary refill time

>2 seconds

Table 2

PERSONAL PRACTICE

PAEDIATRICS AND CHILD HEALTH 31:6 253 Ó2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

resistant pathogens. Enteral administration of antibiotics is as

effective as intravenous. This reduces the need for cannulation

and can be continued in the community effectively.

3

Intravenous

antibiotics may be required where complications are suspected or

when the enteral route is poorly tolerated.

3

Macrolide antibiotics

(e.g. azithromycin, clarithromycin) are second line treatment if

there is an unsatisfactory response to amoxicillin or in instances

where an atypical pneumonia is suspected. Co-amoxiclav may be

a better first line antibiotic in children with complex needs asso-

ciated with a poor cough and swallowing dysfunction for whom

anaerobic bacteria may be easily aspirated.

Figure 4 illustrates a suggested stepwise approach to the

diagnosis and management of children with suspected

pneumonia.

Complications

Most children with community-acquired pneumonia go on to

make a full recovery. However, both pulmonary and systemic

complications occur in around 3%,

5

resulting in significant

morbidity and mortality. Regular reassessment of a child with

pneumonia is recommended, including for children managed in

the community. Increased effort of breathing, agitation and

persistent or swinging fevers should prompt parents to return for

further assessment and it is important that this information is

provided. Pulmonary complications include parapneumonic

effusion, empyema and lung abscess. Systemic complications can

include multi organ failure, metastatic infection, bacteraemia and

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS).

Empyema and pleural effusion

A pleural effusion is a collection of fluid in the space between the

lungs and the chest wall (the pleural space) (see Figure 5). When

this pleural fluid is pus or infective then it is termed an empyema.

They occur in 1% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia.

However, in patients needing hospital admission this may be up

to 40%.

5

Empyema should be suspected if fevers are persisting

on adequate treatment for 48 hours, or there has been 7 days of

persistent fever. The investigation of choice is a chest X-ray to

identify fluid in the pleural space and ultrasound to estimate the

volume of the fluid present.

Intravenous antibiotic therapy is necessary in these patients to

provide a broader coverage and higher penetrance of the pleural

space.

3

Local microbiology advice should be sought to guide the

antimicrobial treatment but should ensure cover for S. pneumo-

niae. These children often require a prolonged course of enteral

antibiotics (1e4 weeks), even once the intravenous antibiotics

have been discontinued.

Effusions which compromise respiratory function should not be

managed by antibiotics alone and early insertion of a chest drain

should be considered. Chest drains should be placed under ultra-

sound guidance and a small bore (including pig tail) drain should be

considered ahead of large bore surgical drains where possible.

Intrapleural fibrinolytics shorten hospital stay and are rec-

ommended for any complicated parapneumonic effusion. Pa-

tients should be considered for surgical treatment (including

video assisted thoracoscopy (VATS)) if they have persistent

sepsis in association with a pleural collection despite chest tube

drainage and antibiotics.

15

Necrotising pneumonia and lung abscess

Lung abscess is a collection of pus within the lung tissue and is

considered a very rare but significant complication in children,

due to its high rates of mortality and long-term implications. This

occurs when there is liquefactive necrosis (in which the lung

tissue is digested by hydrolytic enzymes resulting in a circum-

scribed lesion containing pus) of lung tissue (secondary to

infection) causing the formation of a cavity containing inflam-

matory cells, bacteria and frank pus.

Lung abscess may be identified on chest X-ray by the presence

of a cavity with an air-fluid level. A bronchopleural fistula may

form, leading the abscess into the pleural space with subsequent

formation of an empyema or pneumothorax.

Treatment includes a prolonged course of intravenous anti-

biotics. Percutaneous CT guided drainage of the abscess may be

required and in cases where there is progressive lung paren-

chymal necrosis, segmental or lobar resection may be necessary.

Long term complications of these conditions can occur

causing bronchiectasis, scarring and chronic cough.

16

Pneumatocoele

Pneumaotocoeles are intrapulmonary air-filled cysts. As a

consequence of pneumonia, the bronchus may become narrowed

by inflammatory exudates, leading to the formation of a ball

valve that causes distal dilatation of the alveoli as air is able to

enter the cystic space but not leave it.

Pneuomatocoeles appear as thin-walled cystic spaces con-

taining air (see Figure 6). If they are imaged during the early

stage of the infection, they may have surrounding consolidation

which makes it difficult to distinguish from an abscess.

The main significance of pneumatocele is that it must be distin-

guished from other cavitary pulmonary lesions such as an abscess in

order to avoid unnecessary invasive interventions. Most pneuma-

tocoeles spontaneously resolve over time (usually by six weeks)

following appropriate treatment of the underlying infection.

Decompression is considered when the pneumatocoele is large

enough to compress adjacent lung and mediastinal structures.

Follow up

BTS guidelines do not recommend routine follow up imaging in

uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia. If complica-

tions arise such as empyema or persistent lobar collapse, then

this may warrant follow up X-ray.

5

Interestingly, children with a

round pneumonia who respond to antibiotics do not require

follow up radiograph (unlike the management of this phenome-

non in adults).

17

Future developments

Bedside ultrasound

Ultrasound is diagnostic tool currently used in many paediatric

intensive care settings and could reduce the need for radiation

exposure and chest x-rays in the future. The benefits of ultra-

sound include the absence of radiation and also high

PERSONAL PRACTICE

PAEDIATRICS AND CHILD HEALTH 31:6 254 Ó2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

6

6

7

7

8

8

1

/

8

100%