a v a i l a b l e a... j o u r n a l h o m...

Epidemiology, Staging, Grading, and Risk Stratification of

Bladder Cancer

Marc Colombel

a,

*, Mark Soloway

b

, Hideyuki Akaza

c

, Andreas Bo

¨hle

d

, Joan Palou

e

,

Roger Buckley

f

, Donald Lamm

g

, Maurizio Brausi

h

, J. Alfred Witjes

i

, Raj Persad

j

a

Department of Urology, Claude Bernard University, Ho

ˆpital Edouard Herriot, Lyon, France

b

Department of Urology, University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, Florida, USA

c

Department of Urology, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

d

Department of Urology, HELIOS Agnes Karll Hospital, Bad Schwartau, Germany

e

Department of Urology, Fundacio

´Puigvert, Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

f

Department of Urology, North York General Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

g

Department of Surgery, University of Arizona; BCG Oncology, Phoenix, Arizona, USA

h

Department of Urology, AUSL Modena Estense and B Ramazzini Hospitals, Modena, Italy

i

Department of Urology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

j

Department of Urology/Surgery, Bristol Royal Infirmary and Bristol Urological Institute, Bristol, United Kingdom

european urology supplements 7 (2008) 618–626

available at www.sciencedirect.com

journal homepage: www.europeanurology.com

Article info

Keywords:

Bladder cancer risk factors

Epidemiology

Grading

Non–muscle invasive

bladder cancer

Risk stratification

Staging

Please visit

www.eu-acme.org/

europeanurology to read and

answer questions on-line.

The EU-ACME credits will

then be attributed

automatically.

Abstract

Context: Understanding the epidemiology and risk factors for non–muscle invasive blad-

der cancer (NMIBC) can assist in the prevention and early detection of the disease.

Furthermore, staging, grading, and risk stratification are critical for determining the most

appropriate management strategies for NMIBC based on risk of recurrence and progres-

sion.

Objective: To provide community urologists with an overview of the epidemiology of

NMIBC as well as current approaches to staging, grading, and risk stratification.

Evidence acquisition: A committee of internationally renowned leaders in bladder cancer

management, known as the International Bladder Cancer Group (IBCG), identified current

key influencing guidelines and published English-language literature related to the

epidemiology, staging, and grading of NMIBC available as of March 2008. The IBCG met

on four occasions to review the main findings of the identified literature and the current

clinical practice guidelines of the European Association of Urology (EAU), the First

International Consultation on Bladder Tumors (FICBT), the National Comprehensive

Cancer Network (NCCN), and the American Urological Association (AUA).

Evidence synthesis: Based on this review, the IBCG provided a summary on the epidemiol-

ogy of NMIBC and recommendations for the staging, grading, and risk stratification of the

disease.

Conclusions: Urologists should record the smoking habits of patients and monitor for

possible occupational exposure to urothelial carcinogens. The tumour-node-metastases

(TNM) classification for tumour staging and both the World Health Organization (WHO)

1973 and 2004 grading systems should be applied for appropriate staging and grading of

NMIBC. Urologists should also consider the use of the European Organisation for Research

and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk tables for risk stratification of NMIBC based on risk

of disease recurrence and progression.

#2008 European Association of Urology. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author. Service D’Urologie – CHU Edouard Herriot, 5 place d’Arsonval,

cedex 03, 69437 Lyon, France. Tel. +33 472 11 62 89; Fax: +33 472 11 05 82.

E-mail address: [email protected] (M. Colombel).

1569-9056/$ – see front matter #2008 European Association of Urology. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.eursup.2008.08.002

1. Introduction

A thorough understanding of the epidemiology of

bladder cancer can assist in the prevention and early

detection of the disease. In addition, staging, grading,

and risk stratification are essential for determining

the most appropriate management strategies for

non–muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) based

on risk of recurrence and progression. Therefore, a

committee of internationally renowned leaders in

bladder cancer management, known as the Interna-

tional Bladder Cancer Group (IBCG), identified current

key influencing guidelines and published English-

language literature related to the epidemiology,

staging, and grading of NMIBC available as of March

2008. The IBCG met on four occasions to review the

main findings of the identified literature and the

current clinical practice guidelines of the European

Association of Urology (EAU), the First International

Consultation on Bladder Tumors (FICBT), the

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),

and the American Urological Association (AUA). This

article provides a summary of the epidemiology of

NMIBC and the IBCG’s recommendations for staging,

grading, and risk stratification of the disease based on

currently available guidelines and evidence.

2. Incidence

Bladder cancer ranks ninth in worldwide cancer

incidence. It is the 7th most common cancer in men

and the 17th most common cancer in women [1].

Globally, the incidence of bladder cancer varies

significantly, with Egypt, Western Europe, and North

America having the highest incidence rates, and

Asian countries the lowest rates (see Fig. 1)[2].

Although the disease may occur in young persons,

>90% of new cases occur in persons 55 yr of age [3].

3. Risk factors

Thetwomostwell-establishedriskfactorsfor bladder

tumours are cigarette smoking and occupational

exposure to urothelial carcinogens [4,5]. Cigarette

smoking is the most important riskfactor, accounting

for 50% of cases in men and 35% in women [5]. In fact,

cigarette smokers have a 2- to 4-fold increased risk of

bladder cancer compared to non-smokers [6],and

the risk increases with increasing intensity and/or

duration of smoking [7]. Upon cessation of cigarette

smoking, the risk of bladder cancer falls >30% after

1–4 yr and >60% after 25 yr [7,8] but never returns to

the level of risk of non-smokers.

Occupational exposure to urothelial carcinogens

is the second most important risk factor, accounting

for 5–20% of all bladder cancers [9,10]. The relative

risk of occupational exposure to carcinogens is likely

underestimated and varies from country to country.

Current or historical exposure to aromatic amines

(eg, benzidine, 2-naphthylamine, 4-aminobiphenyl,

o-toluidine, and 4-chloro-o-toluidine) used in the

chemical, rubber, and dye industries [11–13] and

polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) used in the

aluminum, coal, and roofing industries [14] have all

been associated with the development of bladder

cancer. An increased risk of bladder cancer has also

been reported in painters, varnishers, and hair-

dressers [15].

Other environmental exposures that have been

associated with bladder cancer include chronic

urinary tract infections [16], cyclophosphamide

use [17], and exposure to radiotherapy [18]. Recently,

the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic

Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) group found an

increased incidence of bladder cancer in men with

prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy [19].

Inadequate consumption of fruits, vegetables,

and certain vitamins may also play a role in the

development of bladder cancer. A meta-analysis by

Steinmaus et al [20] found that increased risks of

bladder cancer were associated with diets low in

fruit intake (relative risk [RR], 1.40; 95% confidence

interval [CI], 1.08–1.83), and slightly increased risks

were associated with diets low in vegetable intake

(RR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.01–1.34). Evidence also suggests

that garlic [21] and vitamin A [22] have chemo-

protective effects in bladder cancer. Furthermore, a

small randomised study of 65 patients with transi-

tional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the bladder found that

megadoses of vitamins A, B6, C, and E plus zinc

decreased bladder tumour recurrence in patients

receiving bacillus Calmette-Gue

´rin (BCG) immu-

notherapy [23]. Large-scale prospective, randomised

trials are required to clarify the role of vitamins in

bladder cancer prevention.

Although it has been suggested that coffee

consumption and artificial sweeteners may be asso-

ciated with an increased risk of bladder cancer,

results from epidemiologic studies investigating

these agents have been inconclusive. A major

problem in evaluating the independent effect of

coffee consumption on the development of bladder

cancer is its relationship to cigarette smoking [1].To

avoid the residual confounding effect of cigarette

smoking, a pooled analysis of studies examining non-

smokers in Europe was performed. Although the

study was limited by bias in control selection, the

investigators observed a significant increased risk of

european urology supplements 7 (2008) 618–626 619

bladder cancer only in subjects consuming 10 cups

of coffee per day (odds ratio [OR], 1.8; 95% CI, 1.0–3.3)

[24]. Furthermore, most epidemiologic studies have

failed to show any evidence of bladder carcinogeni-

city with saccharin and other sweeteners [1]. In 1999,

the International Agency for Research on Cancer

(IARC) concluded that saccharin and its salts were not

classifiable as carcinogenic in humans, despite

evidence suggesting that sodium saccharin causes

urothelial bladder tumours in experimental animals

[25].

Familial bladder cancer is rare compared to the

familial occurrence of cancer in other tumour sites.

However, there does appear to be an increased risk

Fig. 1 – Worldwide age-standardised incidence rates (per 100 000) for bladder cancer in (a) males and (b) females [2].*

* Reprinted from Ferlay et al [2].

european urology supplements 7 (2008) 618–626620

of bladder cancer in individuals with a family history

of cancer, particularly in those with first-degree

relatives who developed bladder cancer at age 60 yr

or earlier [26]. A population-based, family case-

control study by Aben et al [27] found an almost

2-fold increased risk among first-degree relatives of

patients with urothelial cell carcinoma, which could

not be explained by smoking. A segregation analysis

of >1100 families could not find strong evidence of

inheritance of bladder cancer through a single major

gene. However, the investigators could not exclude

the possibility of an inherited subtype of bladder

cancer. A major gene may segregate in some

families, but this effect may have been masked in

a background of high sporadic incidence [28].

4. Major pathologic subtypes

TCC is the most common primary pathologic

subtype of bladder cancer and is observed in >90%

of tumours [29]. Squamous cell carcinoma and

adenocarcinoma are less common and occur in

approximately 5% and 1% of bladder cancers,

respectively [30,31]. Secondary carcinomas can

appear in the colon, uterus, ovaries, and prostate,

as well as lymphomas.

In certain regions of the world where schistoso-

miasis (also known as bilharziasis) infection is

endemic, squamous cell carcinoma can account for

up to 75% of bladder cancers [32,33]. Schistosomiasis

is a parasitic disease caused by various species of

flatworm. It typically affects agricultural commu-

nities, particularly those dependent upon irrigation

to support their agriculture. Areas with a high

prevalence of schistosomiasis include Africa, the

Caribbean, South America, East Asia, and the

Middle East.

Recently, variants of TCC (nested and micropa-

pillary) have been noted that may have prognostic

and therapeutic significance [34,35]. Results from a

recent study suggest that intravesical therapy may

be ineffective in patients with the micropapillary

variant, and that radical cystectomy may be the

preferred treatment option for patients with this

form of TCC [36]. However, Gaya et al [37] recently

noted good results with intravesical BCG in patients

with a micropapillary pattern and without conco-

mitant carcinoma in situ (CIS).

5. Staging and grading

Stage and grade are significant prognostic factors for

recurrence, progression, and survival and, therefore,

are critical for the appropriate treatment and

management of NMIBC.

5.1. Staging

The most widely used and universally accepted

staging system is the tumour-node-metastases

(TNM) system shown in Table 1 [38]. Under this

system, NMIBC includes (1) papillary tumours

confined to the epithelial mucosa (stage Ta); (2)

tumours invading the subepithelial tissue (ie,

lamina propria; T1); and (3) Tis (CIS).

5.2. Grading

Traditionally, bladder carcinomas have been graded

according to the World Health Organization (WHO)

1973 grading of urothelial papilloma: well differ-

entiated (G1), moderately differentiated (G2), or

poorly differentiated (G3). In 2004, the WHO and

Table 1 – 2002 TNM classification of urinary bladder

cancer [38]

T: Primary tumour

TX Primary tumour cannot be assessed

T0 No evidence of primary tumour

Ta Non-invasive papillary carcinoma

Tis Carcinoma in situ: ‘‘flat tumour’’

T1 Tumour invades subepithelial

connective tissue

T2 Tumour invades muscle

T2a: Tumour invades superficial muscle

(inner half)

T2b: Tumour invades deep muscle

(outer half)

T3 Tumour invades perivesical tissue:

T3a: Microscopically

T3b: Macroscopically

T4 Tumour invades any of the following:

prostate, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall,

abdominal wall

T4a: Tumour invades prostate, uterus,

or vagina

T4b: Tumour invades pelvic wall or

abdominal wall

N: Lymph nodes

NX Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0 No regional lymph node metastasis

N1 Metastasis in a single lymph node 2cm

in greatest dimension

N2 Metastasis in a single lymph node >2cm

but not >5 cm in greatest dimension, or

multiple lymph nodes, none >5cmin

greatest dimension

N3 Metastasis in a lymph node >5cmin

greatest dimension

M: Distant metastasis

MX Distant metastasis cannot be assessed

M0 No distant metastasis

M1 Distant metastasis

european urology supplements 7 (2008) 618–626 621

the International Society of Urological Pathology

(ISUP) published a new grading system that employs

specific cytologic and architectural criteria [39,40].

The new WHO/ISUP classification differentiates

between papillary urothelial neoplasms of low

malignant potential (PUNLMP) and low-grade and

high-grade urothelial carcinomas. Comparisons of

the 1973 and 2004 classification systems are shown

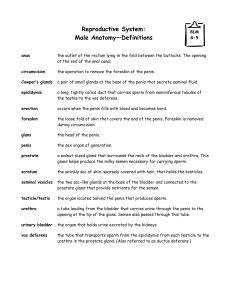

in Table 2 and Fig. 2 [41].

Use of the 2004 WHO/ISUP classification should

result in more uniform diagnoses of tumours that

are better stratified according to risk potential.

However, according to the EAU guidelines for non–

muscle invasive disease, both the 1973 and 2004

WHO classifications should be used for tumour

grading until the 2004 grading system is validated in

more clinical trials [42,43].

Evidence suggests that the WHO/ISUP 2004 classi-

fication does not increase the inter-observer repro-

ducibility of non–muscle invasive tumours compared

to the 1973 WHO classification. Reproducibility is

particularly low for the 2004 PUNLMP classification

(50%). However, differentiation between low-grade

and high-grade urothelial carcinoma using the 2004

classification does have a high inter-observer repro-

ducibility (84–90%) [44–46].

Urologists should interact with their pathologists

to determine which grading system they are using.

Regardless of the grading method utilised, it is

important that the urologist review the pathology

slides with the pathologist.

6. Risk stratification and progression

Approximately 75–80% of bladder tumours present

as non–muscle invasive disease and the remainder

present as muscle-invasive disease [47]. In NMIBC,

approximately 70% present as Ta lesions, 20% as T1

lesions and 10% present as CIS or Tis lesions [6].

NMIBC represents a heterogeneous group of

tumours with completely different oncologic

outcomes. Low-grade tumours, for example, have a

modest recurrence rate but are at low risk for

progression. High-grade tumours, on the other hand,

are associated with significant recurrence, progres-

sion, and mortality rates.

This heterogeneity in bladder tumours compli-

cates the ability to compare the efficacy of different

treatment modalities and thereby establish unified

treatment recommendations. Therefore, risk strati-

fication is imperative for classifying patients with

similar risks of recurrence and progression, and it

helps to determine the appropriate management

strategies for each risk category.

To date, the European Organisation for Research

and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk tables are

considered the most reliable tools for estimating

progression and/or recurrence of NMIBC. The EORTC

scoring system combines data on previous tumour

recurrence rate, number of tumours, tumour dia-

Table 2 – World Health Organization (WHO) grading of

urinary tumours in 1973 and 2004 [39,40]

WHO 1973

Urothelial papilloma

Grade 1: well differentiated

Grade 2: moderately differentiated

Grade 3: poorly differentiated

WHO 2004

Urothelial papilloma

PUNLMP

Low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

High-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma

PUNLMP = papillary urothelial neoplasms of low malignant

potential.

Fig. 2 – Comparison of the 1973 and 2004 World Health Organization (WHO) grading systems.

Some 1973 WHO grade 1 carcinomas are reassigned to the papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential

(PUNLMP) category and others to the 2004 WHO low-grade carcinoma category. Similarly, 1973 WHO grade 2 carcinomas

are reassigned, some to the low-grade carcinoma category and others to the high-grade carcinoma category. All 1973 WHO

grade 3 tumours are assigned to the 2004 WHO high-grade carcinoma category.

TCC = transitional cell carcinoma.

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier Inc [41].

european urology supplements 7 (2008) 618–626622

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

1

/

9

100%