The Evolving Relationship of Social Class to Tobacco Smoking

jnci.oxfordjournals.org JNCI |Editorials 285

The article by Menvielle et al. ( 1 ) in this issue of the Journal fits into

the epidemiological tradition of testing how well one scourge

explains another. Its goal is to quantify the extent to which educa-

tional and socioeconomic differences in smoking in Western

Europe account for social class differences in lung cancer occur-

rence. Complicating this effort, however, is that the relationships

between social class, smoking, and lung cancer have not been static

but have evolved over the last 50 years, following historical trends

in the dissemination of manufactured cigarettes ( 2 ). In Europe,

dependence on manufactured cigarettes spread from men to

women, from North to South, and from higher to lower social

classes ( 2 – 4 ).

Vestiges of this demographic progression can be seen in

studies conducted early in the 20th century that showed no

association between low socioeconomic status and higher risk of

lung cancer ( 5 ). No disparity in lung cancer was seen among

men in England and Wales in 1910 – 1912 and 1930 – 1932,

The Evolving Relationship of Social Class to Tobacco Smoking

and Lung Cancer

Michael J. Thun

Affiliation of author: American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA.

Correspondence to: Michael J. Thun, MD, MS, American Cancer Society,

Atlanta, GA 30303-1002 (e-mail: [email protected] ).

DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djp005

© The Author 2009. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

For Permissions, please e-mail: [email protected].

among women in Sweden in the 1960s, or in older birth cohorts

in Finland from 1971 to 1985. Not until the 1970s were lung

cancer incidence and death rates consistently higher among

men with lower social status ( 2 , 5 ), especially in Northern

Europe ( 2 , 5 ).

Very different socioeconomic patterns in cigarette smoking

and lung cancer are still seen in Southern Europe, where the

social class gradient is reversed among women and much

weaker among men than in the North. Menvielle et al. observe

this among participants in the European Prospective

286 Editorials |JNCI Vol. 101, Issue 5 | March 4, 2009

Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Men and women from

the five countries representing Northern Europe (United

Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands)

were more likely to smoke if they had completed college than if

their education had stopped at primary school. In contrast,

women from Southern Europe (Spain, Italy, and Greece) were

more likely to smoke if they had progressed further in their

education. For men, the educational gradient was in the same

direction, but weaker in Southern Europe than in Northern

Europe.

In this context, it is extremely diffi cult for Menvielle et al. to

disentangle the historical and birth cohort effects of lifetime smok-

ing on lung cancer risk from any other factors that may have con-

tributed to risk. The authors ’ conclusion that “self-reported

differences in smoking consistently explain approximately 50%” of

the educational inequalities in lung cancer is contingent on the

quality of the individual measurement of lifetime smoking and the

ability of the study to distinguish fi xed relationships from those

that are dynamic and evolving.

The design of the study is straightforward. The analyses are

based on approximately 391 000 men and women recruited in nine

countries (excluding France) in Western Europe between 1992

and 1994. At enrollment, respondents 40 – 65 years of age were

asked to report their highest level of education, smoking status

(current, former, never), number of cigarettes currently smoked

per day, age at starting, years of smoking, and various dietary fac-

tors including fruit and vegetable consumption. A total of 1631

incident cases of lung cancer were identifi ed in follow-up through

2004 or 2006.

Although the study design is simple, its results are diffi cult to

compare with those of cohort studies in North America because

educational levels are defi ned differently in Europe and because

the educational gradient in lung cancer risk is expressed in

terms of relative index of inequality (RII). In Europe, a primary

school education corresponds to the fi rst 5 – 9 years of educa-

tion. This varies slightly among countries, ranging from grades

1 – 5 in Germany and Italy to grades 1 – 9 in the United Kingdom.

The RII approach is useful in comparing these countries

because it allows for the different distributions of educational

attainment that exist among these countries. However, the

results cannot be compared with related fi ndings in the United

States because the RII compares risk at the very bottom of the

educational hierarchy (zero percentile) with that for the very

top (100th percentile). These values are approximately 30%

larger than the educational gradients typically reported in the

United States, which compare the average risk in the lowest

educational category to the average risk in the highest educa-

tional category ( 6 ).

The strengths of the study are its size, the availability of pro-

spectively collected information on smoking and diet for each

participant, and the quality of the follow-up information, which

includes data on histological subtypes of lung cancer. The analyses

provide strong evidence that variations in the consumption of

fruits and vegetables, at least as measured by food frequency ques-

tionnaires, account for almost none of the educational gradient in

lung cancer risk.

The main limitations of the study are two: 1) the information

on smoking behavior is based on a single, relatively short ques-

tionnaire that covers only some of the parameters of lifetime

smoking, and 2) the study population is drawn from countries

that represent different phases of the changing relationship

between cigarette smoking and social class. Together, these

limitations leave considerable room for misclassifi cation of life-

time smoking behavior. For example, the analyses cannot con-

sider the number of cigarettes smoked per day at various points

in the past, the use of pipes or cigars instead of cigarettes, or

other product variations such as fi ltered vs nonfi ltered. The

intensity with which each cigarette was smoked cannot be mea-

sured adequately by questionnaires. One could hypothesize that

less affl uent smokers may smoke each cigarette more intensively

than those with more economic resources. Misclassifi cation of

smoking behavior may also be somewhat greater when question-

naires are administered to less educated subjects vs more edu-

cated subjects ( 7 ).

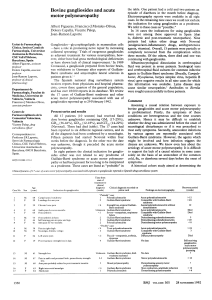

In some analyses, the authors combine data in a manner that

reduces the contrast in risk between never- and ever-smokers or

that aggregates geographic areas with very different relationships

between smoking and social class. For example, fi gure 1 combines

never-smokers with occasional smokers, light smokers, and “ex-

smokers who stopped a long time ago” to improve the precision of

the rate estimates among those considered to have minimal smok-

ing. This does add precision, but it infl ates the apparent risk among

never-smokers. Furthermore, Tables 3, 5, and 6 and Figure 1 com-

bine the data from Northern and Southern Europe. Although these

analyses control for the center at which participants were enrolled,

the consequence of combining regions with very different socio-

economic relationships is to underestimate the contribution of

smoking to the educational gradient in lung cancer.

In conclusion, it is extraordinarily diffi cult to quantify the

degree to which social class differences in tobacco smoking

account for the socioeconomic differences in lung cancer in a

setting in which all of these factors have changed dramatically

over time. Menvielle et al. are almost certainly correct that some

fraction of the socioeconomic differences in lung cancer are due

to factors other than smoking. Their efforts to quantify this

fraction are laudable, even if the collective impact of factors

other than smoking ultimately proves to increase lung cancer

risk by a lower factor (perhaps 1.4) rather than by 2.0 or more.

They are also correct that in the near term and for the foresee-

able future, the most effective approach to reducing both the

socioeconomic disparities and the overall burden of lung cancer

is to implement measures that we already know are effective in

reducing tobacco use.

References

1. Menvielle G , Boshuizen H , Kunst AE , et al . The role of smoking and diet in

explaining educational inequalities in lung cancer incidence . J Natl Cancer

Inst . 2009 ; 101 ( 5 ): 321 – 330 .

2. Mackenbach JP , Huisman M , Andersen O , et al . Inequalities in lung can-

cer mortality by the educational level in 10 European populations . Eur J

Cancer . 2004 ; 40 ( 1 ): 126 – 135 .

3. Huisman M , Kunst AE , Mackenbach JP . Educational inequalities in

smoking among men and women aged 16 years and older in 11 European

countries . Tob Control . 2005 ; 14 ( 2 ): 106 – 113 .

jnci.oxfordjournals.org JNCI |Editorials 287

4. Graham H . Smoking prevalence among women in the European com-

munity 1950 – 1990 . Soc Sci Med . 1996 ; 43 ( 2 ): 243 – 254 .

5. Faggiano F , Partenan T , Kogevinas M , Boffetta P . Socioeconomic differ-

ences in cancer incidence and mortality . In: Kogevinas NPM , Susser M ,

Boffetta P , eds. Social Inequalities and Cancer . Lyon: IARC Scientifi c

Publications; 1997:65 – 176 .

6. Kinsey T . Jemal A . Liff J . Ward E . Thun M . Secular trends in mortality

from common cancers in the United States by educational attainment,

1993 – 2001 . J Natl Cancer Inst . 2008 ; 100 ( 14 ): 1003 – 1012 .

7. Wagenknecht LE , Burke GL , Perkins LL , Haley NJ , Friedman GD .

Misclassifi cation of smoking status in the CARDIA study: a comparison of

self-report with serum cotinine levels . Am J Public Health . 1992 ; 82 ( 1 ): 33 – 36 .

1

/

3

100%