Licence « Economie Gestion » 3 année – Parcours Magistère

Licence « Economie Gestion » 3

ème

année – Parcours Magistère

Développement économique

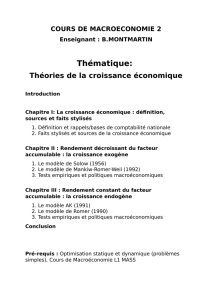

Macrodynamique – Chapitre V

P. Combes Motel

Macro-économie dynamique. Deuxième partie : le postulat des rendements non décroissants : la croissance

endogène.

15 déc. 09

© P. Combes Motel

i

Chapitre V.

L’équilibre avec différenciation des biens : l’équilibre à la

Chamberlin

I. L’équilibre à la Chamberlin

II. Le fonctionnement décentralisé de l’économie

III. Les défaillances des marchés

Encadré 1 ................................................................................................................................................................ 1

Encadré 2. Le caractère délibéré de la recherche développement........................................................................... 1

Encadré 3. Allyn Abbott Young.............................................................................................................................. 1

Encadré 4. Effet externe inter-temporel de la connaissance.................................................................................... 2

Tableau 1. Typologie des biens selon leur degré d’exclusivité ............................................................................... 1

Tableau 2. Les caractéristiques de la fonction de production de connaissances ..................................................... 2

Aghion, P. & P. Howitt, 1992 “A Model of Growth through Creative Destruction” Econometrica, vol. LX, pp.

323-51

Aghion, P. & P. Howitt, 1997 Endogenous Growth Theory, MIT Press.

Brasseul, J. 2004 Histoire des faits économiques et sociaux, Armand Colin.

Darreau, P. 2003 Croissance et politique économique, De Boeck. Ouvertures Economiques, Balises.

Dixit, AK. & JE. Stiglitz, 1977 “Monopolistic Competition and Optimum Product Diversity” The American

Economic Review, vol. 67, n° 3, June, pp. 297-308.

Foray, D. 2000 L’économie de la connaissance, La Découverte. Repères #302.

Griliches, Z. 1979 “The Search for R&D Spillovers” Scandinavian Journal of Economics, vol. 94, pp. 29-47.

Grossman, GM. & E. Helpman, 1995 Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy, 5

th

edition, MIT Press.

Guarino ; A. & M. Iacopetta 2002 « A conversation with Will Baumol on Capitalism, Innovation and Growth »

disponible en ligne : www.prism.gatech.edu/~mi26/int_baumol.pdf

Hall, RE. & CI. Jones, 1999 “Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others” The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 114, n° 1, February, pp. 83-116.

Jones, CI. & J.C. Williams, 1998 “Measuring the Social Return to R&D” The Quarterly Journal of Economics,

vol. 113, n° 4, November, pp. 1119-35.

Jones, CI. 1995 “R & D-Based Models of Economic Growth” The Journal of Political Economy, vol. 103, n° 4,

August, pp. 759-784

Bibliographie

Sommaire

Macro-économie dynamique. Deuxième partie : le postulat des rendements non décroissants : la croissance

endogène.

15 déc. 09

© P. Combes Motel

ii

Jones, CI. 2000 Théorie de la croissance endogène, De Boeck. Ouvertures Economiques, Prémisses.

Koyama, M. 2006 “Increasing returns and the division of labour” Oxonomics, vol. 1, pp.21-24

Laïdi, Z. 2004 La grande perturbation, Flammarion. Champs Sciences Humaines.

Lucas, RE. 1988 “On the Mechanics of Economic Development” Journal of Monetary Economics, vol. 22, n° 1,

July, pp. 3-42.

Porter, M. E. & S. Stern 2000 “Measuring the ‘Ideas’, Production Functions: Evidence from International Patent

Output” NBER Working Papers #7891.

Romer, D. 1997 Macroéconomie approfondie, Ediscience et Mac Graw Hill.

Romer, PM. 1990 “Endogenous Technical Change” Journal of Political Economy, vol. 98, n° 5, part II, S71-

S102.

Young, A. 1928 “Increasing Returns and Economic Progress” Economic Journal, vol. 38, n° 152, December, pp.

527-42.

Macro-économie dynamique. Deuxième partie. Le postulat des rendements non décroissants : les théories de la

croissance endogène. Chapitre V : l’équilibre à la Chamberlin

15 déc. 09

© P. Combes Motel

1

Encadré 1

« Virtuellement, tout l’accroissement de la production, survenu depuis le 18

ème

siècle peut en fin de compte être

attribué à l’innovation. Sans elle, le processus de croissance aurait été insignifiant »

Source : Guarino ; A. & M. Iacopetta 2002

Encadré 2. Le caractère délibéré de la recherche développement

“Growth in this model is driven by technological change that arises from intentional investment decisions made

by profit-maximizing agents. The distinguishing feature of the technology as an input is that it is neither a

conventional good nor a public good; it is a nonrival, partially excludable good. Because of the nonconvexity

introduced by a nonrival good, price-taking competition cannot be supported. Instead, the equilibrium is one with

monopolistic competition.

[…] technological change arises in large part because of intentional actions taken by people who respond to

market incentives. Thus the model is one of endogenous rather than exogenous technological change. This does

not mean that everyone who contributes to technological change is motivated by market incentives. An academic

scientist who is supported by government grants may be totally insulated from them. The premise here is that

market incentives nonetheless play an essential role in the process whereby new knowledge is translated into

goods with practical value. Our initial understanding of electromagnetism arose from research conducted in

academic institutions, but magnetic tape and home videocassette recorders resulted from attempts by private

firms to earn a profit.”

Source: Romer, PM. 1990, p. S71

Encadré 3. Allyn Abbott Young

Allyn A. Young (1876-1929) a enseigné, notamment à Harvard. Il est le premier américain à obtenir un poste de

professeur dans une université anglaise, en l’occurrence à la London School of Economics. Il meurt en 1929,

quelques mois après la publication de l’article intitulé « Increasing returns and economic progress » dans

l’Economic journal (1928, volume 38, p. 527-542) que dirigeait à l’époque Keynes. Schumpeter tient Young en

très haute estime : « Voici un grand économiste, un théoricien brillant, qui est en passe d’être oublié », écrit-il

dans Histoire de l’analyse économique (1954, tome III, Gallimard, 1983, p.177). De fait, à quelques mois de la

crise de 1929, son analyse arrive un peu à contretemps. Surtout, la subtilité de son propos le rend impropre à la

formalisation, ce qui lui vaudra d’être rejeté (par exemple par Romer, in « Increasing returns and long term

growth », Journal of Political Economy, 1986, vol. 94, n°5, qui regrette que ses idées ne puissent donner de

modèle mathématique).

Source : Idées, n° 131, mars 2003, pp. 1-8

Tableau 1. Typologie des biens selon leur degré d’exclusivité

Exclusivité élevée Exclusivité faible

Rivalité Services rendus par

un avocat, balladeur,

disquette

Ressources

maritimes (eaux

territoriales)

Pesticides, pâturages

communs, ressources

maritimes (eaux

internationales)

Non rivalité Chaînes TV codées,

autoroutes à péage

Accès salle

informatique,

principe actif de

médicaments

protégés par brevet

Manuel d’économie

dans une

bibliothèque

universitaire

Défense et sécurité

nationales, R&D

fondamentale,

Algèbre, couche

d’ozone

Source : Jones, CI. 2000

Macro-économie dynamique. Deuxième partie. Le postulat des rendements non décroissants : les théories de la

croissance endogène. Chapitre V : l’équilibre à la Chamberlin

15 déc. 09

© P. Combes Motel

2

Encadré 4. Effet externe inter-temporel de la connaissance

“The first substantive assumption is that devoting more human capital to research leads to a higher rate of

production of new designs. The second is that the larger the total stock of designs and knowledge is, the higher

the productivity of an engineer working in the research sector will be. According to this specification, a college-

educated engineer working today and one working 100 years ago have the same human capital, which is

measured in terms of years of forgone participation in the labor market. The engineer working today is more

productive because he or she can take advantage of all the additional knowledge accumulated as design problems

were solved during the last

100

years.”

Source: Romer, PM. 1990, p. S83

Tableau 2. Les caractéristiques de la fonction de production de connaissances

Agents privés Planificateur central

Fonction de production des

connaissances

(

)

A

LA ⋅=− µψ1

&

(

)

A

LA ⋅=− µψ1

& avec

φ1λ

µµ AL

A−

=

c’est-à-dire :

(

)

φλ

µψ

1

ALA A⋅⋅=−

&

Effet marginal travail

L

A

sur la

création de connaissances

µ

µ

λ

λ

> 1 : rendement

social > rendement

privé

Evolution de l’effet marginal de

L

A

sur la création de

connaissances

0

(

)

A

L

1

µ1λλ −

λ

< 1 : rendement

social décroissant

Effet marginal de

A

sur la

création de connaissances

0

A

L

A

µφ

φ

> 0 : rendement

social > rendement

privé

Evolution de l’effet marginal de

A

sur la création de

connaissances

0

( )

2

µ1φφ A

L

A

− φ < 1 : rendement

social décroissant

1

/

5

100%