cahier de recherche

1

Cahier de Recherche 21

CAHIER DE

RECHERCHE

N°21

Décembre 2014

Institut de Recherche en Management et en

Pratiques d’Entreprise

The Groupe ESC PAU Institute for Research in

Management and Best Practices

2

Cahier de Recherche 21

Sommaire

TRANSFERTS DE FONDS, CAPACITE D’ABSORPTION ET SYNDROME

HOLLANDAIS : CAS DU MAROC

PAR FARID MAKHLOUF

P.3

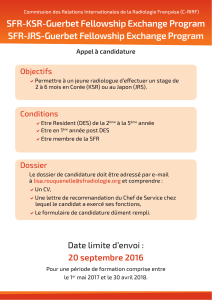

THE IMPACT OF EXCHANGE RATE POLICY ON REMITTANCES IN

MAROCCO : A THRESHOLD VAR ANALYSIS

PAR FARID MAKHLOUF P.25

DOES EDUCATION MATTER FOR THE ADOPTION OG

INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES (ICT) IN

DEVELOPING COUNTRIES? EVIDENCE FROM SENEGAL

PAR MAZHAR MUGHAL, BARASSOU DIAWARA P.45

3

Cahier de Recherche 21

Transferts de fonds, capacité

d’absorption et syndrome

hollandais : cas du Maroc

Farid MAKHLOUF

Professeur Groupe ESC Pau

IRMAPE

4

Cahier de Recherche 21

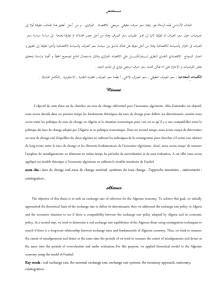

RESUME

Pour le Maroc, les transferts de fonds des migrants augmentent de manière continue

et constituent une source non négligeable de financement. Ce papier diagnostique

la présence du syndrome hollandais au Maroc. Pour ce faire, il examine la relation

entre les transferts de fonds et le taux de change réel effectif. En utilisant la

technique bayésienne, nous avons trouvé que les transferts de fonds n’engendrent

pas une appréciation du taux de change effectif.

Mots clés : Maroc, Transferts de fonds, Syndrome hollandais, Analyses bayésiennes

ABSTRACT

Migrant remittances are a steadily rising external source of capital for Morocco, and

constitute a large source of income. This paper studies the empirical relationship

between remittances and Dutch disease in Morocco. To do this, it examines the

relationship between remittances and the real effective exchange rate. Using the

Bayesian technique, we found that remittances do not cause the appreciation of

Morocco’s real exchange rate.

Keywords: Morocco, Remittances, Dutch Disease, Bayesian analysis

5

Cahier de Recherche 21

INTRODUCTION

Les transferts de fonds représentent un phénomène complexe. Ce qui a suscité un foisonnement

d’études et de recherches ces dernières années. De plus, les transferts de fonds effectués par les

migrants vers leur pays d’origine constituent une source de financement importante pour un bon

nombre de pays en développement, le Maroc en fait partie (Makhlouf, 2013). Cette manne financière

peut être utilisée dans les pays en développement comme un substitut à d’autres flux financiers afin

de promouvoir leurs institutions économiques et financières. A cet égard, beaucoup de pays en

développement utilisent cette source pour financer leur développement local (Grabel, 2008).

Cependant, les effets des transferts de fonds sur les économies des pays d’origine restent ambigus.

Pour certains économistes, ces transferts ont un impact positif sur la balance des paiements (Chami

et al., 2005). Pour d’autres, ils peuvent avoir des effets inflationnistes et apprécient le taux de change

en causant ce que l’on appelle le « syndrome hollandais

1

» (Bourdet et Falck, 2006). Les effets macro-

économiques des transferts de fonds des migrants sont donc complexes (Grabel ,2008) et diffèrent

d’un pays à l’autre. Ceci est dû principalement aux politiques économiques mises en place dans les

pays d’origine des migrants, mais aussi à la manière selon laquelle ces transferts sont utilisés. De

plus, la plupart des gouvernements des pays en développement interviennent de manière fréquente

sur le marché des changes

2

(Krugman et Obstfeld, 2011, p.492).

La littérature économique souligne les risques d’appréciation du taux de change suite aux transferts

de fonds, puisque cela peut provoquer des pertes de compétitivité prix pour les pays bénéficiaires. Par

exemple, Amuedo-Dorantes et Pozo (2004) montrent en utilisant les données de panel pour 13 pays

d’Amérique Latine et des Caraïbes, qu’une augmentation de 100% des envois de fonds engendre une

appréciation de 22% du taux de change réel. Ce risque peut être plus important dans les petits pays

(Kapur, 2004).

Dans ce papier, nous allons étudier, nous vérifierons l’hypothèse selon laquelle les transferts de fonds

provoquent le syndrome hollandais, en étudiant leur impact sur le taux de change effectif et sur la

réallocation des ressources.

La suite de travail sera organisée comme suit : la deuxième section traite la revue de la littérature

selon deux approches; dans la troisième section, nous testerons l’hypothèse selon laquelle les

transferts de fonds engendrent le syndrome hollandais dans le cas du Maroc en utilisant deux types

d’estimations (fréquentiste et baysésienne) ; enfin dans la dernière section nous conclurons ce travail.

1

Le syndrome hollandais se réfère à l’appréciation de la monnaie suite à une entrée massive de capitaux.

2

Il est à signaler que dans un système de change flexible, le taux de change corrige le déséquilibre de la balance courante.

Dans un régime de taux de change fixe, la variation de la balance courante engendre une variation de la masse monétaire.

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

38

38

39

39

40

40

41

41

42

42

43

43

44

44

45

45

46

46

47

47

48

48

49

49

50

50

51

51

52

52

53

53

54

54

55

55

56

56

57

57

58

58

59

59

60

60

61

61

62

62

63

63

64

64

65

65

66

66

67

67

68

68

69

69

70

70

71

71

72

72

73

73

74

74

75

75

76

76

77

77

78

78

79

79

1

/

79

100%