RF Theory and Design Notes - Resonator Theory & Electromagnetic Cavities

Telechargé par

richard.trimaud

RF Theory and Design - Notes

Jeremiah Holzbauer Ph.D.

USPAS - Grand Rapids

June 2012

1 Introduction

This document is a short summary of the theory covered in the USPAS class Applied

Electromagnetism for Accelerator Design. This is a living document, and will be expanded

at a future date, please excuse small errors and sudden transitions. This document is

Version 1.

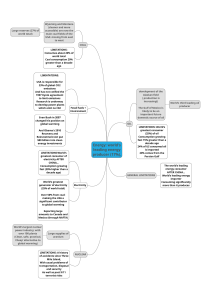

2 Resonator Theory

This section will provide insights for use in further sections by producing a generic formal-

ism to describe resonators with the explicit goal of treating resonating cavities with the

same mathematical treatment. Starting from the simple harmonic oscillator, damping and

driving terms will be added, and their effects derived. The treatment of electromagnetic

resonators by this formalism with then be justified, and a special case of interest will be

presented.

2.1 The Ideal Harmonic Oscillator

The ideal, linear oscillator is the most basic starting point for solving many problems in

physics. This is especially true in accelerator physics because so many of the phenomena of

accelerator physics can be treated as purely classical and having few confounding effects.

The harmonic oscillator, without damping, has the form

d2x

dt2+ω2

0x= 0 (1)

where x(t) is the oscillating position at time t, and ω0is the oscillation frequency. The

general solution for this is characterized by an amplitude A and a phase ϕ

x(t) = Acos (ω0t+ϕ).(2)

1

2.2 The Driven, Damped Harmonic Oscillator

For this to be a useful model we must consider damping. The form of damping that is of

interest to us (because it is the form of the losses in a resonator), is damping proportional

to the change in “position”, which has a form of

d2x

dt2+γdx

dt +ω2

0x= 0,(3)

where the damping coefficient γhas the dimension of frequency. This type of equation has

different forms of solution depending on the strength of the damping. If we choose the

damping to be weak, the general solution to this equation has the form

x(t) = Ae−γ1tcos (ω1t+ϕ) (4)

where

ω1=ω01−γ2

4ω2

0

(5)

and

γ1=1

2γ. (6)

Note that adding damping shifts the resonator frequency based on how strong the damp-

ing is. From this we can define a “quality factor” Qwhich is related to the rate at which

the resonator loses energy. Qis defined by the equation Q=ω0/2γwith weak damping

characterized by Q≫1. For a typical superconducting cavity, Qis generally ∼5×109,

justifying the assumption of weak damping.

The effects of a driving term must also be considered. For an arbitrary driving term of

the form f(t), the differential equation becomes

d2x

dt2+γdx

dt +ω2

0x=f(t),(7)

with the solution (for γ= 0)

x(t) = x0cos ω0t+˙x0

ω0

sin ω0t+1

ω0t

0

sin ω0t−t′f(t′)dt′(8)

where x0and ˙x0are the initial position and velocity. The third term of this solution gives

the contribution from the driving term, and it is worthwhile to notice that a harmonic

driving term with frequency equal to the resonant frequency of the oscillator will produce

the largest oscillations, as expected.

2

2.3 Oscillator Behavior Near Resonance

It is most useful to examine the response of the weakly damped oscillator to driving near

its resonant frequency because this is the desired case for resonator operation. Assuming

a driving term that is purely harmonic (f(t) = f0cos ωt) and ignoring transient behav-

ior yields a solution with a relatively simple form. These assumptions are very justified

in almost every accelerator application; most changes made to the driving term of the

cavity have a time scale much larger than the RF period (which is usually on the order

of nanoseconds). This type of differential equation is solved quite simply by assuming a

complex solution and writing

d2Ξ

dt2+γdΞ

dt +ω2

0Ξ = f0e−iωt (9)

with x(t) = ℜΞ(t). We are seeking a solution of the form Ξ(t) = Ξ0e−iωt where Ξ0is also a

complex number of the form Ξ0=|Ξ0|eiϕ. Solving for the real variable of interest xgives

x(t) = ℜΞ(t) = ℜ(|Ξ0|e−iωt+iϕ) = |Ξ0|cos (ωt −ϕ). Plugging this form of the solution into

the differential equation gives

−ω2−iωγ +ω2

0Ξ0=f0(10)

simplifying to

Ξ0=f0

ω2

0−ω2−iωγ (11)

with squared amplitude of

|Ξ0|2=f2

0

(ω2

0−ω2)2+ω2γ2.(12)

The resulting behavior can be see in Figure 1 for a variety of damping coefficients γ[1].

Again, it is easy to see that the maximum response will be shifted slightly depending on

the strength of the damping. This shift can be neglected for γ≪ω0, and as demonstrated

earlier, this is a very good approximation for superconducting resonators. Another impor-

tant feature of these curves is the characteristic width of each curve. This width (∆ω),

defined as the width at the level that is 3 dB below the maximum response, is equal to 2γ

where γis the damping parameter. An alternative and equivalent definition of the Quality

Factor is Q=ω/∆ω.

The phase response of Ξ is also of interest. This phase ϕcan be interpreted as the

difference in phase between the driving term and the response of the resonator, and is an

important quantity for resonator control.

tan (ϕ) = ℑΞ0

ℜΞ0

=ωγ

ω2

0−ω2=ω

ω01

1−ω

ω02γ

ω0(13)

3

Figure 1: Resonant curves for damped, driven harmonic oscillator with γ= 0.5, 0.2, 0.1, 0

A plot of ϕcan be seen in Figure 2. The most important feature of this behavior is the

nearly linear region near resonance. Most cavity control systems treat the cavity response

as linear and must operate in this region to remain stable.

2.4 Special Case: The Duffing Equation

As we shall see, certain non-linear behavior in superconducting resonators in operation can

be well modeled by the Duffing Equation. The Duffing Equation adds a weakly non-linear

term to the restoring force such that

d2x

dt2+γdx

dt +ω2

0x+αx3=f0cos ωt. (14)

For the purposes of this application, it can be assumed both the damping, driving, and

non-linear terms are small compared to the frequency ω0. Additionally, we will only look

for solutions where ω≃ω0. Using the standard van der Pol transformation [2], seen in

Figure 3, we transform into a rotating coordinate frame. Using the transformations

u=xcos ωt −˙x

ωsin ωt (15)

4

Figure 2: Oscillator phase shift compared to driving term versus detuning. Note the nearly

linear region near resonance.

and

v=−xsin ωt −˙x

ωcos ωt, (16)

we arrive at the following differential equations for uand v:

˙u=1

ω[−(ω2−ω2

0)(ucos ωt −vsin ωt)−ωγ(usin ωt +vcos ωt)

+α(ucos ωt −vsin ωt)3−f0cosωt] sin ωt (17)

˙v=1

ω[−(ω2−ω2

0)(ucos ωt −vsin ωt)−ωγ(usin ωt +vcos ωt)

+α(ucos ωt −vsin ωt)3−f0cosωt] cos ωt. (18)

Because we are assuming small non-linearities and constant frequency (ω), we are only

interested in the average behavior of these functions. Averaging over a period of 2π/ω, we

get

˙u=1

2ω−ωγu + (ω2−ω2

0)v−3

4α(u2+v2)v(19)

and

˙v=1

2ωωγv −(ω2−ω2

0)u+3

4α(u2+v2)u−f0.(20)

5

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

38

38

39

39

40

40

41

41

42

42

43

43

44

44

45

45

46

46

47

47

48

48

49

49

50

50

51

51

52

52

53

53

54

54

55

55

56

56

57

57

58

58

59

59

60

60

61

61

62

62

63

63

64

64

65

65

66

66

67

67

68

68

69

69

70

70

71

71

72

72

73

73

74

74

75

75

76

76

77

77

78

78

79

79

1

/

79

100%