Self-Cleaning Nanofiltration Membranes: Mineralized Interlayer Engineering

Telechargé par

ayoub.belcaid2

Crosslinking mineralized interlayer engineering of in situ self-cleaning

nanoltration membranes based on polyethylene substrates

Yunhuan Chen , Xinyue Liu , Weier Wang , Xiaoxiao Duan

*

, Yongsheng Ren

*

State Key Laboratory of High-efciency Utilization of Coal and Green Chemical Engineering, College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Frontier Science

and Technology, Ningxia University, Yinchuan 750021, PR China

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Nanoltration

Hydrophilic modication

Catalytic self-cleaning

Interfacial polymerization

ABSTRACT

Conventional nanoltration (NF) membranes are limited by their greater thickness and less stable ultraltration

substrates, as well as the signicant challenges posed by membrane fouling. In this work, we developed com-

posite NF membranes with a multifunctional mineralized interlayer through metal polyphenol network (MPN)

precursor-mediated cross-linking mineralization on hydrophobic polyethylene (PE) substrates. The incorporation

of a mineralized layer enhanced the wettability of PE and optimized the structure of polyamide (PA) via an

interlayer modulation strategy, resulting in PA-Fe

3

O

4

-PE membranes exhibiting water permeance up to 21.9

LMH bar

−1

and selectivity up to 68.8 for Cl

-

/SO

4

2-

. Furthermore, PA-Fe

3

O

4

-PE displayed a highly polarized

surface that signicantly improved its antifouling properties. The conned space within PA-Fe

3

O

4

-PE enabled

efcient regeneration through in situ self-cleaning, achieving ux recovery above 95% during all three fouling-

regeneration cycles while maintaining high stability and recoverability under extreme real-world wastewater

conditions. This study provides novel insights into the preparation of multifunctional composite NF membranes

and their sustainable application in water treatment.

1. Introduction

Reversed osmosis (RO) and nanoltration (NF) technologies have

experienced a surge in popularity following the launch of polyamide

(PA) thin lm composite (TFC) membranes [1,2]. These membrane

technologies have rapidly emerged as the dominant players in water

treatment, particularly desalination, due to their numerous advantages

including high energy efciency, treatment efcacy, and small footprint

[3]. In comparison to RO membranes, NF membranes exhibit a slight

compromise in solute rejection capacity while achieving higher water

permeability. However, the combined mechanism of size exclusion and

electrostatic effects endows NF membranes with the capability to

selectively separate charged solutes [4,5]. Despite the promising appli-

cation prospects of NF membranes in material concentration, selective

solute separation, and water purication, their permeability-selectivity

trade-off and inevitable membrane fouling issue pose signicant chal-

lenges to further advancements [6–8]. Consequently, the development

of NF membranes with enhanced permselectivity and antifouling/self-

cleaning properties is crucial for their ideal utilization in water

treatment.

To date, the majority of industrially useful NF membranes have been

obtained by preparing PA layers on porous supports by interfacial

polymerization (IP) [9,10]. Common substrates for preparing TFC

membranes using IP include ultraltration (UF) membranes such as

polysulfone (PSF), polyacrylonitrile (PAN), and polyethersulfone (PES),

which are chosen due to their suitable hydrophilicity and porosity [11].

However, the higher thickness of these UF membranes results in longer

water transport paths and higher transmembrane resistance for the

prepared NF membranes, leading to undesired permeability outcomes

[12–14]. In this case, the utilization of a thin and tough porous substrate

such as commercially available polyethylene (PE) membranes as an

alternative to UF substrates is anticipated to enhance water permeability

[15]. However, despite addressing the issue of inadequate water

permeability caused by thickness and porosity, hydrophobic PE mem-

branes encounter challenges in establishing a continuous water layer on

their surface during IP, thereby rendering the preparation of PA layers

based on PE substrates nearly unattainable [16,17]. Consequently,

enhancing the hydrophilicity of the PE substrate becomes a fundamental

prerequisite for conducting the IP reaction. Hydrophilic treatment of

hydrophobic substrates has been extensively documented, including

plasma-induced grafting of polyethylene glycol (PEG) onto poly(vinyl-

idene uoride) (PVDF) and polypropylene (PP), as well as oxidization of

* Corresponding authors at: No.539, Helanshan West Road, Xixia District, Yinchuan, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, 750021, PR China.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (X. Duan), [email protected], [email protected] (Y. Ren).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Chemical Engineering Journal

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cej

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2024.158926

Received 4 October 2024; Received in revised form 20 December 2024; Accepted 22 December 2024

Chemical Engineering Journal 504 (2025) 158926

Available online 24 December 2024

1385-8947/© 2024 Elsevier B.V. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies.

PP using a chromic acid solution [12,18]. However, these methods are

typically complex and require high energy consumption, potentially

leading to damage to the pore structure of the membrane. Therefore, it is

imperative to explore a gentle and easily controllable method of modi-

cation that is suitable for large-scale applications, thereby enabling its

implementation in industrial manufacturing.

When seeking strategies to overcome this challenge, mussel

chemistry-directed biomimetic coatings offer a glimpse of the solution.

Natural polyphenols possess high interfacial activity and can form

continuous coatings on inert substrates, which have been demonstrated

to gently modify hydrophobic substrates [12,19]. Moreover, metal-

polyphenol networks (MPNs) show great promise in constructing

multifunctional interfacial coatings due to the strong coordination be-

tween metal ions and polyphenols [20–22]. The combination of

different compounds with excellent electronic properties results in new

composite materials, which have attracted great technological interest

in recent years [23]. For instance, MPN can facilitate the mineralization

of metal ions (such as complex iron oxides) to achieve fenton-like cat-

alytic oxidation function [24–27]. Additionally, the mineralized inter-

layer mediated by MPN enhances aqueous-phase monomer storage

capacity and retards monomer diffusion, thereby regulating the IP

process [28]. Distinguished by its deviation from conventional catalyst

preparation methods, this mild mineralization process obviates the need

for intricate procedures, especially for iron spinel compounds [29–31].

In addition, the potential of spinel is conrmed by its biomedical ap-

plications [32]. Therefore, guided by mussel chemistry, MPN deposition

and mineralization may realize our vision of gently modifying PE sub-

strates to construct a multifunctional mineralized coating that includes

hydrophilic modication of PE membranes, interlayer modulation

strategies for optimizing IP reactions, as well as achieving in situ cata-

lytic self-cleaning.

To demonstrate the aforementioned concept, a multifunctional

mineralized coating was fabricated on a hydrophobic PE substrate

through MPN-mediated crosslinking mineralization (Fig. 1a), which

serves three purposes: (i) hydrophilicization of the PE substrate to be

appropriate for the IP reaction; (ii) mineralized interlayer to regulate

the diffusion of monomers in the IP reaction; and (iii) efcient in situ

catalytic self-cleaning via conned spaces constructed by composite

membranes. The resulting NF membranes exhibit exceptional water

permeability, solute separation selectivity, and high surface polarity,

effectively breaking the permeability-selectivity trade-off while

demonstrating excellent antifouling properties. Moreover, due to their

conned space, these composite NF membranes can be regenerated

through rapid in-situ catalytic self-cleaning even under extreme real-

world wastewater conditions while maintaining remarkable stability

and recyclability.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

Commercial PE microporous membranes with a thickness of ~ 20

μ

m

were obtained from SK geo centric Ltd. (Korea). Polysulfone (PSF) ul-

traltration (UF) membranes (MWCO: ~20 kDa) provided by Xiamen

Xuwu Membrane Technology Co. Tris-HCl buffer (1 M, pH =8.8) was

purchased from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology Co. Tannic acid (TA),

FeCl

2

⋅4H

2

O, FeCl

3

⋅6H

2

O, LiCl, NaCl, MgCl

2

, Na

2

SO

4

and MgSO

4

are all

analytically pure (AR) provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co.

Piperazine (PIP, 99.5 %), hexane (AR), ethylene glycol (AR), poly-

ethylene glycol (PEG, WM: 200, 300, 400, and 600 Da, chemically pure

(CP) and sodium alginate (SA, CP) were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin

Biochemical Sci & Tech Co. Trimesoyl chloride (TMC, >98 %) are

purchased from Shanghai McLean Biochemical Technology Co.

2.2. Membrane preparation

The preparation of composite nanoltration (NF) membranes is

divided into two distinct stages: the mineralization process of the

polyethylene (PE) substrate and the subsequent formation of a poly-

amide (PA) layer, as elaborated in Supplementary Information.

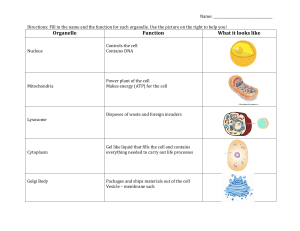

Fig. 1. MPN-mediated in situ cross-linking mineralization. a) Schematic illustration of MPN coating fabrication and in situ cross-linking mineralization inspired by

mussel biochemistry. b-e) Surface SEM images of PE, MPN-PE, and Fe

3

O

4

-PE substrates, and f) cross-section and EDS mapping images of Fe

3

O

4

-PE substrate,

indicative the elemental distribution of C, O, and Fe.

Y. Chen et al.

Chemical Engineering Journal 504 (2025) 158926

2

2.3. Characterization methods

The membrane surface wettability and surface free energy (SFE)

were characterized by measuring the water contact angles (WCAs) and

ethylene glycol contact angles (ECAs) on the membrane surface. Raman

spectroscopy, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, X-ray

photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and energy-dispersive X-ray spec-

troscopy (EDS) were employed to analyze the chemical composition of

the membrane. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force

microscopy (AFM) were utilized for observing the morphology of the

membrane. A comprehensive introduction to membrane characteriza-

tion is provided in Supplementary Information.

2.4. Membrane separation assay

The membrane separation and fouling/regeneration experiments

were conducted using a at plate cross-ow device with a membrane

cell effective area of 24 cm

2

in this study. Supplementary Information

provides detailed information on the experimental process and meth-

odology related to membrane separation, fouling, and regeneration.

2.5. Computational simulation

The Gaussian 09 software was employed for structure optimization

and binding energy calculations, based on Density Functional Theory

(DFT) with the B3LYP exchange–correlation functional [33]. For main

group elements, the 6-311G** basis set was utilized, while for the

transition metal element iron (Fe), the SDD pseudopotential basis set

was employed to enhance calculation accuracy. Additionally, Multiwfn

software was used to perform electrostatic potentials and differential

charge densities analysis [34].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Mpn-mediated cross-linking mineralization

The process of mineralization/hydrophilic modication of the

polyethylene substrate is depicted in Fig. 1a, and the entire minerali-

zation process was conducted under mild room temperature conditions.

Importantly, conventional metal oxide preparation involves oxidative

processes where excess and deciency of oxygen can increase or

decrease the degree of oxidation of the 3d-metal [35]. In contrast, the

MPN-mediated mineralization process has no complex reaction steps,

and the entire mineralization process relies on a single control variable,

time, and is therefore easily manageable in an industrial manufacturing

process. According to the proposed scheme, MPN is deposited onto the

polyethylene substrate as the initial mineralization precursor, thereby

providing a plethora of reaction sites for subsequent crosslinking

mineralization reactions. A brous structure was observed for the

nascent PE substrate (Fig. 1b), while EDS mapping of its surface and

cross-section only revealed the distribution of elemental C (elemental H

could not be detected by EDS). The loading of MPN resulted in the

emergence of randomly dispersed nano-dots on the surface of MPN-PE

(Fig. 1c), accompanied by the presence of elemental O and Fe, which

were absent in the PE substrate, as observed through both surface and

cross-section mapping (Fig. S2b). Upon completion of crosslinking

mineralization, uniform and dense nanoparticles formed on the surface

of Fe

3

O

4

-PE (Fig. 1d–e), leading to a certain degree increase in surface

roughness (Fig. S3). It is well known that the electronic properties for

the complex oxides strongly depend on the average crystallite size and

crystallite size distribution [36]. Thus, the dense nanoparticles on

Fe

3

O

4

-PE potentially allow for superior electronic properties. According

to Wenzel’s model [37]. the nanoscale surface protrusions can signi-

cantly augment the hydrophilicity of the membrane surface, thereby

rendering the Fe

3

O

4

-PE substrate amenable for implementation in the IP

process. Moreover, uniform distribution of O and Fe elements was

observed on both the surface and cross-section of Fe

3

O

4

-PE membranes

through membrane surface and cross-section morphology analysis and

EDS mapping (Fig. 1f and Fig. S2). This nding suggests that MPN-

mediated cross-linking mineralization not only occurs on the mem-

brane surface but also within its pores. Due to the abundance of hydroxyl

groups in MPN, the MPN-mediated cross-linking mineralization process

not only yields compact nanoparticles but also introduces a signicant

number of hydrophilic functional groups onto the PE substrate, thereby

substantially enhancing its water wettability. In accordance with the

dissolution-diffusion model, hydrophilic membranes exhibit a steeper

concentration gradient for water during operation, facilitating efcient

water transport [3].

To gain further insights into the mineralization process of cross-

linking, Raman spectra were acquired for the three substrates (Fig. 2a).

In the case of MPN-PE and Fe

3

O

4

-PE, evidence of catechol coordination

with Fe

3+

(Fe-O resonance) was observed within the range of approxi-

mately 530–640 cm

−1

, while novel peaks arising from C-OH vibrations

and C-O-Fe

3+

coordination were detected at 1342 and 1472 cm

−1

[19,38]. These ndings provide conrmation regarding the incorpora-

tion of TA and MPN networks onto PE substrates. Additionally, a weak

peak at 680 cm

−1

is observed for Fe

3

O

4

-PE, which can be attributed to

the formation of Fe

3

O

4

minerals [39]. Normally, it would be necessary to

determine the atomic positions of the cations in the initial Fe

3

O

4

singlet,

or whether other phases and composites would form [40]. However, in

this paper the source of the iron in Fe

3

O

4

can be clearly identied as Fe

2+

and Fe

3+

, thus discharging the possibility of forming other composites.

As depicted in Fig. 2b, with respect to atomic composition, MPN-PE

exhibits a lower Fe content (0.22 %) on its surface, while Fe

3

O

4

-PE

demonstrates higher loading of Fe (8.86 %) and O (32.21 %), attributed

to the continuous crosslinking mineralization process. The O 1 s and Fe

2p XPS spectra of MPN-PE and Fe

3

O

4

-PE were analyzed to investigate

the chemical compositional shifts during the mineralization process

(Fig. 2c). Deconvolution of the O 1 s spectrum revealed the presence of

–OH, C =O, and C-O peaks in MPN-PE, while the Fe 2p spectrum

exhibited a characteristic peak corresponding to Fe (III) [41]. For Fe

3

O

4

-

PE (Fig. 2d), the signal of Fe-O from metal oxides was additionally

detected in the deconvolution of its O1s, as well as its Fe 2p was shown

to be a mixed valence of Fe (II) and Fe(III) [42]. By combining different

types of polymer with oxides and carbon-based materials the new

composites with increased and attractive electronic properties could be

fabricated[43]. It is noteworthy that the high abundance of Fe

2+

in-

dicates the presence of signicant oxygen vacancies in the Fe

3

O

4

coating, which effectively facilitates the activation of H

2

O

2

and the

generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) components [44]. More-

over, oxygen vacancies effect on exchange interactions [45]. This in situ

degradation/mineralization process of pollutants based on the Fenton

reaction is exactly the mechanism of action of catalytic self-cleaning in

this work.

The thickness of the Fe

3

O

4

coating can be estimated by determining

the average pore diameter before and after mineralization. As depicted

in Fig. 2e, the virgin PE membrane had an average pore diameter of

121.5 nm, whereas that of Fe

3

O

4

-PE was reduced to 108.4 nm, indi-

cating a mineralized coating thickness of approximately 6.6 nm

(Fig. S4). Although a reduction in pore size may reduce the water

transport channels within the membrane[46], this change in ux due to

the change in pore size is negligible since the pristine PE substrate has no

water ux at low pressures (2 bar) (Fig. 2f). The pristine PE substrate

exhibited a water contact angle (WCA) of 104.1◦, indicating complete

hydrophobicity and resulting in a high liquid breakthrough pressure

(LEP) of 19.3 bar at 2 bar[47]. In contrast, the Fe

3

O

4

-PE membrane with

inside-out hydrophilic modication showed a reduced WCA of 50.5◦and

LEP decreased to 0.7 bar, leading to a dry membrane ux of 19.7 LMH

and an impressive wet membrane ux as high as 102.9 LMH under an

operating pressure of 2 bar. In conclusion, the afore mentioned char-

acterization results conrm that MPN-mediated crosslinking minerali-

zation enables the formation of a Fe

3

O

4

mineralized layer on

Y. Chen et al.

Chemical Engineering Journal 504 (2025) 158926

3

Fig. 2. Physicochemical properties of the original and modied substrates. a) Raman spectroscopy and b) XPS analysis of PE, MPN-PE and Fe

3

O

4

-PE substrates. XPS

O1s and Fe 2p spectra of c) MPN-PE and d) Fe

3

O

4

-PE. e) Pore size distribution and f) WCA, LEP, and water ux (2 bar) of PE and Fe

3

O

4

-PE (where the wet membrane

was obtained by pre-soaking for 1 h in DI).

Fig. 3. Interaction mechanism of MPN precursors. a1-a2) Optimized structure of TA molecule (substituted with a gallate branch) and its spatial arrangement of

electron cloud. b1, c1) Equilibrium conguration of Fe

3+

interacting with the ester group /phenolic hydroxyl group (b/c), b2, c2) Corresponding electron cloud

arrangement, b3, c3) The 3D isosurfaces depicting electron density difference and b4, c4) 2D contour maps near the ester group /phenolic hydroxyl group. The blue

and yellow surfaces in the 3D isosurfaces represent values equivalent to 0.001 and −0.001, respectively. The dashed blue and solid red lines in the 2D contour maps

correspond to regions where there is a decrease and an increase in electron density, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this gure legend,

the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Y. Chen et al.

Chemical Engineering Journal 504 (2025) 158926

4

hydrophobic PE substrate. Simultaneously, this process effectively en-

hances the hydrophilicity of the PE substrate, thereby facilitating the

preparation of composite NF membranes via IP.

3.2. Mechanism of MPN-mediated cross-linking mineralization

As proposed, MPN precursors serve as both modiers of membrane

surfaces and crucial agents in the formation and stabilization of Fe

3

O

4

coatings. The MPN with Fe

3+

as a cross-linking center provides reaction

sites and nucleation sites necessary for achieving the mineralization

transformation of Fe

3

O

4

[24]. Furthermore, it is imperative to consider

that the strength of the interaction between Fe

3+

and TA exerts a sub-

stantial inuence on the process of mineralization [39,48]. Therefore, it

is imperative to analyze the molecular interactions between Ta and

Fe

3+

. The interaction between TA molecules and Fe

3+

in aqueous solu-

tion was assessed using density-functional theory (DFT). To streamline

the calculations, gallic acid branches were employed as a simplied

representation of TA. The optimised molecular structure of TA and its

electron cloud arrangement are depicted in Fig. 3a1-a2, where the ester

group and phenolic hydroxyl group are predicted to interact strongly

with Fe

3+

. Specically, the O-Fe bond formed by the ester group exhibits

a binding energy of −3.79 eV at a distance of 2.02 Å from Fe

3+

(Fig. 3b1). On the other hand, the phenolic hydroxyl group forms an O-

Fe bond with a relatively longer distance (2.44 Å) from Fe

3+

, resulting in

a binding energy of −3.03 eV (Fig. 3c1). In comparison, the binding

energy of Fe

3+

to the phenolic hydroxyl group was slightly lower than

that of the ester group, probably due to the more distant spatial location.

However, it should be noted that chelating coordination among neigh-

boring hydroxyl groups may lead to a more signicant interaction than

what is calculated [25]. The electron cloud distributions before and after

TA binding to Fe

3+

(Fig. 3a2, b2, and c2) exhibit a pronounced

augmentation in the electron density surrounding Fe

3+

, thereby indi-

cating the occurrence of electron transfer from the ester group/phenolic

hydroxyl group to the adjacent Fe

3+

ion, which facilitates the binding of

Fe

3+

. To gain further insights into the variations in electron density

during the action of MPN precursors, the different charge densities of

ester groups and phenolic hydroxyl groups before and after their inter-

action with Fe3 +were investigated. As shown in Fig. 3b3 and c3

(representing ±0.001 isosurfaces; other scenarios are illustrated in

Fig. S5 and S6), the interaction between TA and Fe

3+

results in a sphe-

roidal electron-rich (blue) structure encompassing the iron nucleus,

irrespective of the Fe

3+

site of action. From the 2D contour maps

(Fig. 3b4 and c4), the center of this electron-rich structure surrounding

the Fe nucleus exhibits an electron-decient blue dashed line, indicating

an electron-integration interaction between TA and Fe

3+

. Furthermore,

the O-Fe interaction leads to enhanced electron density around Fe

3+

,

Fig. 4. Morphological characteristics, compositional analysis, and inherent properties of polyethylene-based composite NF membranes. a) Surface SEM, b) Surface

AFM and c) Separation layer thickness characterization of PA- Fe

3

O

4

-PE membrane. d) Surface XPS spectra of PE substrate and PA-Fe

3

O

4

-PE membrane. e) WCA and

SFE of several substrates and PA- Fe

3

O

4

-PE membrane. f) Repulsion curves of PA- Fe

3

O

4

-PE towards uncharged solute (PEG) and its pore diameter distribution. g)

Comparison of pore size ranges (All apertures with a probability density greater than 0.005 in the PDF curve were counted) of conventional PA-PSF and PA- Fe

3

O

4

-PE

membranes prepared by IP on PSF and Fe

3

O

4

-PE substrates. h) WP and rejection of prepared PA- Fe

3

O

4

-PE membranes for treatment of inorganic salt solutions (2000

ppm, 7 bar). i) Comparative analysis of permeability and separation selectivity (Cl

-

/SO

4

2-

) between PA- Fe

3

O

4

-PE membranes and NF membranes on

different substrates.

Y. Chen et al.

Chemical Engineering Journal 504 (2025) 158926

5

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

1

/

10

100%