The exclusion of pregnant women from an Ebola vaccine trial in Boende,

western DRC: Perceptions of female participants who became pregnant and

community members

Maha Salloum

a,b,*

, Ynke Larivi`

ere

a,b

, Freddy Bikioli Bolombo

a,b,c

, Tr´

esor Zola Matuvanga

a,b,c

,

Gwen Lemey

a,b

, Vivi Maketa

c

, Hypolite Muhindo-Mavoko

c

, Pierre Van Damme

a

,

Patrick Mitashi

c

, Hilde Bastiaens

b,d

, Jean-Pierre Van Geertruyden

b

, Antea Paviotti

a,b

a

Centre for the Evaluation of Vaccination, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Institute, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

b

Global Health Institute, Department of Family Medicine and Population Health, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

c

Tropical Medicine Department, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo

d

Primary & interdisciplinary Care, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Pregnant women

Exclusion

Vaccine trials

DRC

Ebola

ABSTRACT

Pregnant women are often underrepresented in clinical trials. However, there is a growing push for more in-

clusion after multiple disease outbreaks, like COVID-19, Zika, and Mpox disproportionately affected them.

Qualitative research has primarily focused on the experiences of pregnant women who choose to participate or

decline participation in trials. To our knowledge, there has been no research on the perspectives of those who

were excluded from trials upon becoming pregnant. To address this gap, we explored the views of women

excluded from a phase 2 Ebola vaccine trial, as well as those of the broader community in Boende, Democratic

Republic of the Congo. Through individual interviews and focus group discussions, we found that protecting the

foetus was paramount for the women, leading to general acceptance of their exclusion from the trial. Trust in

trial organisers’ knowledge, and the absence of an active Ebola outbreak at the time of the trial, may have

supported this acceptance. Community perceptions generally aligned with those of the excluded women inter-

viewed. However, the exclusion seemed to have impacted the decision to participate for a proportion of women

of reproductive age. This was observed when some interviewed women reported declining participation in the

trial due to their desire to conceive during the trial period. This study illustrates how women made pragmatic

decisions regarding trial participation within the decision space available to them. Our ndings seem to support

established norms of special care for safety during pregnancy and echo sentiments described elsewhere in the

literature. These results, coupled with the growing demands for the inclusion of pregnant women, highlight the

necessity of nding a balance between prioritising the safety of women and their foetuses, and the autonomy of

pregnant women, enabling them to make informed choices through comprehensible informed consent processes.

1. Introduction

Pregnant women have traditionally been excluded from the majority

of clinical trials [1–3]. The primary reason for this exclusion is the

concern for the safety of foetuses exposed to potential side effects of the

investigational products. Incidents such as the teratogenic effects

observed with drugs like Thalidomide and Diethylstilbesterol in the

1960s and 1970s have played an important role in the elaboration of

stringent guidelines for the inclusion of (pregnant) women in trials

[4,5]. In the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines of 1977,

the exclusion from participation in early-stage clinical trials targeted all

women of reproductive age who were able to get pregnant. Later, the

recommendations slowly became more permissive, and in 1993, the

FDA published new guidelines recommending more gender equality in

clinical trials. However, the lack of inclusion of pregnant women per-

sisted. For example, a 2014 study demonstrated that less than 6 % of US-

approved pharmaceuticals had human pregnancy data [6]. Recent

studies continue to indicate a low percentage of inclusion of pregnant

* Corresponding authors at: Global Health Institute, University of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium.

E-mail address: [email protected] (M. Salloum).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Vaccine

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2025.127000

Received 23 September 2024; Received in revised form 17 February 2025; Accepted 6 March 2025

Vaccine 55 (2025) 127000

Available online 22 March 2025

0264-410X/© 2025 Published by Elsevier Ltd.

women in both vaccine and therapeutic trials. For example, around 80 %

of trials registered for COVID-19 non-biological treatments in July 2020,

and over 90 % of late-stage overall vaccine trials between 2018 and

2023 excluded pregnant women [7,8]. Outbreaks of diseases like Mpox

and Zika further underscored the need for tested drugs and vaccines for

pregnant women, as these infections can lead to severe complications,

including congenital anomalies and adverse pregnancy outcomes

[9,10]. However, there seems to be promising progress in this issue, with

advocacy groups and academic researchers sharing actionable recom-

mendations for increased involvement of pregnant women [11,12].

Additionally, the FDA has issued a guidance document on optimal

practices when including pregnant women in clinical research [13].

Public health emergencies like the Ebola Disease (EBOD) outbreaks

in West and Central Africa highlighted the challenges and importance of

including pregnant women in clinical trials. EBOD is a viral haemor-

rhagic illness with a Case Fatality Rate (CFR) that could reach 90 %, and

is caused by either the Ebola virus (EBOV) -previously known as Zaire

Ebola Virus- or a closely related ortho-ebolavirus species [14]. The rst

ortho-ebolavirus species was identied in 1976 in the Democratic Re-

public of the Congo (DRC), which has witnessed since then 15 EBOD

outbreaks, becoming the country most affected by Ebola worldwide

[15]. Treatment of the disease consists of supportive care and rehydra-

tion uids; recently, two monoclonal antibody treatments against EBOV

have been approved by the FDA [16]. In terms of prophylactic in-

terventions, two vaccines (rVSV-ZEBOV, and Ad26.ZEBOV, MVA-BN-

Filo) have been prequalied for use by the World Health Organisation

(WHO) [17].

Despite contrasting reports on EBOD’s association with the possi-

bility of increased disease severity and mortality risk for pregnant

women, there is a consensus that pregnant women experience “an

increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including foetal loss and

pregnancy-associated haemorrhage” [18]. Nonetheless, the inclusion of

pregnant women in clinical research for Ebola vaccines has been delayed

due to concerns over the unknown potential risks of the investigational

products to pregnant women and their foetuses [19]. This has sparked

numerous debates and calls for their inclusion, especially during the

rollout of the approved rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine in response to the

2018–2020 EBOV outbreak in eastern DRC [20,21]. Eventually, in early

2019, the DRC’s national ethics committee (Comit´

e National d’Ethique de

la Sant´

e) supported including pregnant women in Ebola vaccination

activities in outbreak areas, a decision endorsed by the WHO’s Strategic

Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) [22]. Later in 2019,

a Phase 3 vaccine clinical trial of the Ad26.ZEBOV, MVA-BN-Filo in

DRC’s outbreak-affected regions also included pregnant women [23].

Besides documenting the inclusion of pregnant women in trials and

advocating to increase their participation, researchers have also been

looking into pregnant women’s perceptions of their involvement in

clinical trials [8,24]. Many studies show that pregnant women’s main

fear when considering participating in a clinical trial is the potential

impact on the health of their foetuses [25,26]. However, reports show

that pregnant women’s willingness to participate in clinical trials is, in

most cases, positively correlated with their risk perception of the disease

in question: the more dangerous and locally prevalent a disease or a

medical condition is perceived to be, the more inclined women would be

to enrol in a clinical trial [27,28].

Studies exploring pregnant women’s perceptions mostly interviewed

the ones who chose to participate or declined participation in clinical

trials or asked them questions about hypothetical participation in clin-

ical trials. However, to our knowledge, no existing study attempted to

understand the perceptions of female trial participants who were

excluded from receiving vaccine/drug doses based on their pregnancy

status. To tackle this, our study aimed to explore the perceptions of

women who were excluded from receiving further doses of the Ad26.

ZEBOV, MVA-BN-Filo Ebola vaccine when they became pregnant during

a Phase 2 Ebola vaccine trial in the DRC. The objective is to provide

insight from pregnant women in a remote area of a low-income country

on their motivations for trial participation (before becoming pregnant),

and their perception of their exclusion after a positive pregnancy test.

Furthermore, the article incorporates the views of community members

and healthcare workers, including midwives and nurses, as women’s

choices to (not) participate could be (strongly) inuenced by the per-

ceptions of their families and social circles.

2. Methods

2.1. Study setting

Boende is the capital of Tshuapa province, western DRC. From 26

July until 7 October 2014, an Ebola outbreak took place in the Boende

Health Zone, with a total of 69 suspected, probable, and conrmed cases

reported [29]. At that time, no vaccines or treatments were available. To

prepare for potential future EBOV outbreaks, a Phase 2 Ebola vaccine

trial was conducted between 2019 and 2022 in Boende. The trial tar-

geted the recruitment of 700 healthcare and frontline workers (males

and females) to determine the safety and immunogenicity of the two-

dose Ad26.ZEBOV, MVA-BN-Filo vaccine regimen, followed by a

booster dose of Ad26.ZEBOV one or two years after the administration of

the rst vaccine (clinical trial.gov identier: NCT04186000) [30].

Serious adverse events were recorded from the rst dose until six months

after the booster dose.

Alongside the clinical trial, different qualitative sub-studies were

conducted to explore the acceptance of different aspects of the trial. The

vaccine trial and the qualitative study discussed in this paper are part of

the EBOVAC3 project. Led by an international consortium of academic

institutions, research organisations, and private industry partners, the

project aimed to support an essential part of the remaining clinical and

manufacturing activities required for the licensure of an Ebola vaccine

[31].

Recruitment for the Ebola vaccine trial started in December 2019

and excluded pregnant and breastfeeding women from enrolment. This

exclusion aligns with common practices in Phase 2 clinical trials, where

pregnant women are often not included due to limited safety data. In this

case, the trial organisers chose to exclude because the trial involved a

booster dose, and there was insufcient data on the safety of the

(boosted) vaccine regimen yet. Additionally, the initial trial protocol

stated that every participant who became pregnant during the trial

would immediately be excluded. However, this did not consider the fact

that women who became pregnant between dose 2 and their booster

vaccination (administered one to two years later) were not necessarily

still pregnant or breastfeeding at the time of the booster vaccination. The

protocol was therefore amended to ensure that women who became

pregnant between dose 2 and their booster dose could be vaccinated

with a booster if they were no longer pregnant or breastfeeding at the

time of vaccination. Furthermore, if the pregnancy occurred between

dose 1 and dose 2 of the vaccination regimen, women remained in the

study for safety follow-up until delivery; if the pregnancy occurred after

the administration of the two-dose vaccination regimen, women

remained in the study for both safety and immunogenicity follow-up

until the end of the trial. The trial aspired to cover expenses for

related and non-related (serious) adverse events during the entire trial

period but excluded childbirth expenses, as female trial participants

were advised not to become pregnant during trial participation [32].

Female participants were not offered any contraceptives, but they were

informed before trial enrolment that they could not receive the vaccine

while pregnant or breastfeeding and should use adequate contraceptives

from 28 days prior to the rst dose up to one month after the second dose

and from 14 days before the booster dose until 3 months after the

booster dose. If a participant became pregnant during a pre-dened (and

vaccine-dependent) vaccination window, this would be reported as a

protocol deviation [30]. Pregnancies were followed up until the end of

pregnancy period and the pregnancy outcomes were noted (delivery,

still birth, miscarriage). Hereafter, we use the terms ‘excluded’ and

M. Salloum et al.

Vaccine 55 (2025) 127000

2

‘pregnant women’ to refer to female participants who became pregnant

during the trial and therefore did not receive one of the scheduled

regimen doses, even if they remained in the trial for safety (and

immunogenicity) follow-up visits.

2.2. Qualitative data collection and sampling

This article builds on individual interviews and Focus Group Dis-

cussions (FGDs) conducted in Boende in July/August 2022. In total, 24

women became pregnant during the trial according to pregnancy tests

taken prior to administering any of the vaccine doses. Eight women lived

outside of Boende town. For logistic reasons, we conducted interviews

with 14 women who lived in Boende and had become pregnant during

the vaccine trial. Three of them were excluded from the trial because

they became pregnant before the second dose of the vaccine regimen,

whilst the other 11 became pregnant after the second dose of the vaccine

regimen. Among the latter, 10 women did not receive the booster dose

because they were still pregnant or breastfeeding, while one woman

received the booster dose because pregnancy and breastfeeding ended

before the administration of the booster dose. To enrich the analysis

with broader community perspectives, the study also benetted from

data from four FGDs with nurses and midwives working in Boende who

were sampled by convenience and contacted by the vaccine trial local

study coordinator. Additionally, we drew from secondary data from 30

interviews and FGDs conducted with community members (journalists,

restaurant and hotel managers, and representatives of local human

rights organisations) in Boende who did not participate in the Ebola

vaccine trial. These participants were asked one or two relevant ques-

tions about pregnancy and the Ebola vaccine trial in Boende as part of a

study about the disease and trial perceptions in the community and were

also sampled by convenience. Table 1 shows the gender and profession

of the participants who took part in the interviews and FGDs. Interviews

with the excluded women and FGDs with nurses and midwives were

conducted by MS together with a Lingala-French interpreter, while FB

and AP conducted interviews in Lingala and French with other com-

munity members. The semi-structured interview guide focused on the

perceptions and experiences related to the exclusion decision and

opinions about the trial in general. Some interview questions were

adjusted after the rst three interviews (e.g. changing some probes to

make them clearer to the interviewees). The main interview guide is

uploaded in the supplementary materials. During the data collection

period, peer briengs took place daily to discuss eld notes. The in-

terviews and FGDs were recorded and then transcribed in French with

the support of a translator. All participants provided oral informed

consent. Oral informed consent was chosen for this qualitative study to

accommodate participants with low literacy levels, ensuring compre-

hension and minimising barriers to participation. This approach and the

study protocol received ethics approval from the National Ethics Com-

mittee in DRC (Avis n◦368/CNES/BN/PMMF/2022 du 5/07/2022),

which included approval for the use of oral consent. The data collection

process also involved informal discussions about the study topic with the

interpreter, who was a female doctor living in Boende. We employed the

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ)

checklist to guide our reporting [33].

2.3. Data analysis

French transcripts were uploaded to QSR NVivo V.1.5.1., which was

used to perform the coding. MS and AP used a thematic analysis

approach to analyse and inductively code the data [35,36]. The rst

round of analysis generated initial codes with annotations and a pre-

liminary coding tree. During the second round, codes were rearranged,

renamed, and merged resulting in three main themes. AP and MS

regularly discussed the codes and the major themes identied. Below is a

schematic overview of the three main themes and related subthemes

identied. The quotes reported in the result section of this paper aim to

illustrate the following themes and subthemes.

1. Acceptance of the exclusion rule

a. Foetal safety is paramount

b. Trust in the trial organisers

c. Community trust and concerns

2. Pregnancy concerns

a. Inuence of past experiences

b. Marriage and parenthood options

3. Us and them: trial participants’ sense of superiority

a. Vaccines and sterilisation rumours

b. Medical knowledge and rule acceptance

2.4. Positionality

It is important to look at our results while reecting on the circum-

stances that could have affected the data collected. As the interviewers

were afliated with the trial and the EBOVAC3 project, interviewees’

and participants’ trust in the decision of the trial organisers might have

been emphasised due to desirability bias. Additionally, the fact that two

of the interviewers were (perceived as) white Europeans (MS and AP)

could have encouraged a more positive or accepting sentiment towards

the trial; this was sometimes explicitly mentioned by interviewees and

FGD participants. For example, one participant said: “A white person can

never make a product that can kill people, no. You [white interviewer]

already know how we are, we are suspicious”. The convenience sampling

of participants in community interviews and focus groups may have

introduced some bias, but we tried to mitigate this by conducting a large

number of interviews and focus groups with individuals who live and

work in different parts of Boende.

3. Results

3.1. Acceptance of the exclusion rule

3.1.1. Foetal safety is paramount

Most women who participated in our qualitative study argued that it

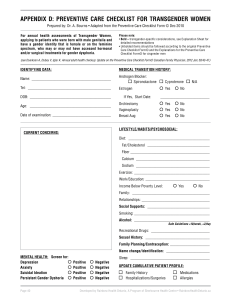

Table 1

Gender and profession of the participants of the interviews and FG

a,b

.

Individual interviews

Trial participants who became pregnant 14

School teachers (men) 2

School teachers (women) 2

Hotel and restaurant managers (men) 2

Hotel and restaurant managers (women) 5

Religious leaders (men) 3

Pharmacists (men) 4

Members of a local citizen movement 4

Total 36

Focus Group Discussions

Vendors (men) 1

Vendors (women) 2

Taximen 1

Relais communautaires (RECO)

a

(women) 1

CODESA

b

(men) 1

Journalists (men) 1

Human rights non-governmental organisation representatives (men) 1

Nurses and midwives (women) (non-participants in the vaccine trial) 4

Total

c

12

a

Relais communautaires are community members who received training in

health communication and volunteer to inform the rest of the community on

different health topics like (non)communicable diseases and vaccination [34].

b

CODESA are committees for the development of the Health Area (sub-divi-

sion of the Health Zone) and represent the institutional link between the health

system and the community.

c

Categories like vendors, restaurant managers, etc.. were identied as

members of relevant social categories to interview to explore how community

members who were not study participants perceived the topic.

M. Salloum et al.

Vaccine 55 (2025) 127000

3

was an appropriate decision to exclude pregnant women from the Ebola

vaccine trial out of concern for the safety of the foetus. During an initial

brieng by the trial team, trial participants were informed that pregnant

and breastfeeding women would not be enrolled in the trial “due to a

lack of sufcient information on the vaccine’s effects on the foetus”.

Therefore, the preventive exclusion of pregnant women seemed

acceptable. As one woman described:

“It was a good decision because the vaccine was [supposed to be] for me

only; we do not know how the baby lives in the womb, and if I take the vaccine

while pregnant, there is a risk that the baby develops malformations”

(interview, trial participant, excluded after becoming pregnant).

3.1.2. Trust in the trial organisers

However, when asked whether they would participate in a vaccine

trial while pregnant if the trial organisers said that pregnant women

could be included, 12 out of 14 of the interviewed excluded women

declared that they would accept to participate. The majority of the fe-

male healthcare workers who did not participate in the trial had the

same view. Their main explanation for this attitude was the desire to be

protected from the disease: “If they invite everybody, without any criteria,

and I happen to be pregnant, I will come to get vaccinated. If they exclude

[pregnant women], I will not come,” one woman concluded (focus group,

non-participant).

These two attitudes -agreeing on the exclusion rule in the Ebola

vaccine trial and accepting to participate in future trials, if allowed-

indicate a signicant degree of trust in the trial organisation. A partic-

ipant excluded from the trial stated that her decision to enrol in future

studies “will depend on the researchers themselves: if they say I can partic-

ipate in their study, then I will participate”.

3.1.3. Community trust and concerns

Among men and women living in Boende who did not participate in

the trial, many saw the decision to exclude pregnant women as appro-

priate out of concern for the safety of the foetus, similar to what was

voiced by the women excluded from the trial after becoming pregnant.

Likewise, many community members explained that their opinion on

whether pregnant women should participate in future trials would

depend on the recommendations of the medical professionals organising

clinical trials as one restaurant manager stated: “Only you doctors know if

pregnant women should not take [the vaccine]. Me, I do not know a lot”

(interview, non-participant). This level of trust, among community

members, may derive from the perception of medical doctors as persons

who are highly educated in matters of health [37]. Nevertheless, some

expressed the concern that pregnant women, if excluded, would not be

protected in the face of possible future Ebola epidemics. For example, a

pharmacist argued that pregnant and breastfeeding women should be

given the vaccine after the end of their pregnancy or breastfeeding

period: “If they are not immunised, when there will be another outbreak, they

will be the rst victims.” He hoped that a vaccine would be developed and

made accessible to everyone, as “the disease does not spare anybody.”

Similarly, an activist working for a human rights organisation under-

lined that pregnant women also deserve a chance at protection: “They

are human beings like us! We were recommended the vaccine, but when is it

going to be recommended for them as well?”. Both quotes show the

importance of pregnant women’s health and protection for the

community.

3.2. Pregnancy concerns

3.2.1. Inuence of past experiences

Whilst most of the interviewed women indicated that they would

have enrolled if pregnant and given the possibility, three women

declared that they would not participate in a future vaccine trial if they

were pregnant. In particular, these women expressed concerns about the

potential effects of the vaccine on the foetus’s health. Two of these three

were trial participants who became pregnant and had complications or

miscarriages during the trial. Following this, they suspected that the

vaccine may have caused their complications. As one woman explained:

“This time, when I became pregnant, I had too many [health issues] […]

and I told myself that it was maybe because of the vaccine. [I had taken] two

doses already, it might have been what has brought me these issues. Then, I

told myself that if there will be another study, if I will be pregnant, I will not

accept any more.” (interview, trial participant, excluded after becoming

pregnant).

Nevertheless, these three women, like the rest of the women inter-

viewed, explicitly stated that if there were an Ebola outbreak, they

would take the risk of participating in the trial even if they were preg-

nant. The search for protection seemed to prevail in the context of an

active outbreak, which is much more fearsome than normal circum-

stances, and thus changed these women’s decision-making process. As

one woman who did not participate in the trial summarised: “Well,

everybody is afraid of dying; if there is an outbreak, I will accept to receive the

vaccine, to be protected!” (focus group, non-participant).

3.2.2. Marriage and parenthood options

The “out if pregnant” exclusion criterion at enrolment, in combina-

tion with the relatively long duration of the trial (two years and 6

months), did not only automatically exclude pregnant women at the

time of recruitment, it also inuenced the decision-making process of

certain non-pregnant women who attended the introductory brieng

sessions of the trial. Certain women explained that they decided not to

participate in the trial because it would have prevented them from

getting pregnant for two years:

“I [decided not to participate] because I saw that I am still young. I do not

know, I might get pregnant during these two years; I am a woman, [and] I can

get married. If my husband demands that we make a child… this is what made

me take a step back and not enrol” (focus group, non-participant).

Meanwhile, other women argued that despite their husbands’

opposing opinions, they chose to enrol and possibly withdraw from the

trial if they became pregnant:

“My husband said: ‘You are a married woman, you want to have children;

why would you want to participate in a study that advises against preg-

nancy?’. But I answered: ‘If I will ever get pregnant, I will stop [participating

in] this study” (interview, trial participant, excluded after becoming

pregnant).

These views demonstrate that the exclusion criterion not only

inuenced women’s decisions regarding trial participation but also

showed their ability to make pragmatic choices that best suited their

circumstances. Rather than being passive, women exercised agency—-

whether by opting out to prioritise future pregnancies or enrolling with

a plan to withdraw if necessary—demonstrating autonomy in balancing

personal goals with trial requirements.

3.3. Us and them: trial participants’ sense of superiority

3.3.1. Vaccines and sterilisation rumours

Contrary to other settings where sterilisation rumours strongly

accompanied vaccine trials and vaccination activities [38], this type of

rumour did exist but did not seem to be widespread in Boende. After

having decided to participate in the trial, women dismissed rumours that

the vaccine could sterilise them. As one participant explained: “Those

who speak are rather those who do not know. But we, who are in the study, we

know that it is not what they say” (interview, trial participant, excluded

after becoming pregnant). Another participant described her reaction to

rumours of sterilisation: “I told them: ‘I told you that the vaccine was not

made to prevent pregnancies. The proof? I got pregnant. So, your rumours are

not true’” (interview, trial participant, excluded after becoming

pregnant).

This goes to show that the participants regarded themselves as more

knowledgeable about the trial compared the rest of the population

which could be the reason why they dismissed some rumours.

M. Salloum et al.

Vaccine 55 (2025) 127000

4

3.3.2. Medical knowledge and rule acceptance

During our conversations with nurses and midwives, we observed a

sense of relative epistemic superiority regarding how their medical

knowledge compared to the rest of the population. This perceived su-

periority may have facilitated their acceptance of the trial’s “pregnancy

exclusion rule”, as adhering to it reinforced their alignment with the

professional standards upheld by the trial staff and organisers. The trial

staff included local doctors and nurses from Boende, professors from

Kinshasa, and international researchers who were only intermittently

present over the course of the study. By accepting the rule, the in-

terviewees might have thought that they could signal their inclusion

within the broader medical community, which contributed to enhancing

the local community’s preparedness for potential lethal healthcare

threats like Ebola. It could also explain the relative scarcity of rumours

surrounding pregnancy and the trial vaccine among this category of trial

participants. One interviewee articulated this sentiment by saying: “It is

important to realise that as a healthcare worker, my reasoning has to be

different from other people’s” (Interview, trial participant, excluded after

becoming pregnant). The same feeling of having different knowledge

levels was expressed by some healthcare providers who did not partic-

ipate in the trial: “I think they [community members] were scared, but as

healthcare workers we have always told them that these people [trial orga-

nisers] do not take blood for [no reason], they are here to protect us.” (focus

group, non-participant).

4. Discussion

The exclusion of pregnant women from the Ebola vaccine trial in

Boende did not seem to face signicant local controversy. Participants

and residents of Boende largely viewed this decision as appropriate,

reecting established social and historical norms regarding the unique

physiology of pregnancy and the potential risks of introducing new in-

terventions during this period [39,40]. Additionally, the absence of an

active Ebola outbreak at the time of the trial may have facilitated the

acceptance of the exclusion rule. All the women interviewed agreed that

in the case of an active Ebola outbreak, they would take the risk of

participating in the trial, even if they were pregnant. This seems to be in

line with the concerns raised by pregnant women in Beni, DRC, excluded

from the Ebola vaccine roll-out during the rst months of the Kivu

outbreak, who claimed that depriving pregnant women of the vaccine

would mean “sending them to death” [41]. Some pharmaceutical com-

panies, however, are beginning to acknowledge and respond to calls for

greater inclusion of pregnant women in clinical trials. While systematic

change remains slow, isolated efforts show growing attention to this

issue. In Rwanda, for instance, where no outbreak exists at the moment,

the pharmaceutical company manufacturing the Ad26-ZOBOV, MVA-

BN-Filo is sponsoring a trial to examine the safety of the vaccine in

pregnant women [42].

Our results also highlighted a great reliance on what trial organisers

allow or suggest. This emerged clearly in answers like “if they say yes, I

participate; if they say no, I do not” that we most often received when

asking about participation in a future hypothetical vaccine trial. This

showed an important externalisation of decision-making and risk man-

agement, within which no other factors like the type of vaccine, the

pregnancy trimester, or other types of information seemed to be taken

into account. Noteworthy is the fact that many of the interviewees were

nurses and midwives, who have a relatively high degree of medical

education and knowledge of women’s health. This could suggest that

other participants who have lower (medical) literacy levels -compared

to the ones we interviewed- could practice even higher levels of

decision-making externalisation. This was observed in a study by Hol-

lander et al. in Accra (Ghana), where pregnant women without a med-

ical background showed reliance on medical doctors’ advice or religious

factors (God’s will) when deciding to participate in clinical trials [43].

On the contrary, a study conducted in Canada reported different answers

to the question about participation in a future hypothetical vaccine trial,

with the majority of women indicating that they “would need to seek

information beyond what the researchers would provide” [26]. This

would put additional ethical responsibility on the researchers in settings

where trial participants regard them as the main source of health in-

formation, as was observed in our study. Women having less access to

health information, which might lead to medical decision externalisa-

tion, appears to be a phenomenon observed in many LMIC settings,

possibly due to connectivity and nancial accessibility challenges, as

well as other barriers [44]. For example, a 2014 survey of demographics

and health (DHS) in the Equateur province in DRC (now administra-

tively restructured into ve provinces including Tshuapa province with

Boende as its provincial capital) revealed that over 40 % of women aged

15–45 do not know how to read and over 80 % in the province do not

access media outlets (radio, newspaper, tv, etc.) for periods of at least

one week at a time [45]. Although these numbers have likely changed in

the past years with the increased reach of the internet and smartphones,

they still give an estimate of literacy and media access in the rural setting

of Boende and possibly in similar settings elsewhere in low-income

countries Such challenges would require trial organisers to pay further

attention, in these settings, to the informed consent and recruitment

process, particularly when recruiting pregnant women. Although the

Ebola vaccine trial in Boende did not include pregnant women, infor-

mation sessions on informed consent were organised in the local lan-

guage prior to inclusion, allowing all (potential) participants to ask

questions. Furthermore, and given the long duration of the trial, the

participants had to re-consent and take the test of understanding again

before getting the booster dose one or two years following the rst dose

[46].

When analysing pregnant women’s attitudes towards clinical trial

participation, we need to discern between trials for therapeutic medi-

cines and those for vaccines targeting healthy populations. Prior

research suggests that pregnant women might be more accepting of

therapeutic trials compared to vaccines [26,47]. This could be due to the

difference in perceived risks; therapeutic trials aim to alleviate existing

conditions and recruit patients already suffering from specic illnesses,

whereas vaccines aim to provide protection from possible future in-

fections and target healthy volunteers. However, the risk perception

may also be inuenced by the prevalence and lethality of the disease

against which the vaccine is being tested, and our ndings support this

argument. In Boende, an area with a history of Ebola and Mpox out-

breaks, most women indicated a willingness to participate in a hypo-

thetical vaccine trial. Conversely, interviews with women from

European countries revealed a general reluctance to participate in

maternal vaccine trials [25]; notably, these interviews were conducted

before the COVID-19 pandemic, when no large threat of active infectious

disease existed in Europe. On the other hand, a survey of 128 women in

the United States around the time of the Zika virus epidemic in South

America showed that over 77 % of pregnant women and new mothers

would accept to participate in a vaccine trial for the Zika virus [48].

These observations highlight that disease prevalence and risk perception

can inuence pregnant women’s decisions regarding clinical trial

participation. In some settings, pregnant women are more compelled or

have no other choice but to participate, due to higher disease risk. This

being said, the calls for more inclusion of pregnant women in vaccine

research do not assume that all pregnant women at serious risk of con-

tracting a prevalent disease would want to participate in clinical trials

[49]. Rather, the calls aim to provide these women with the tools and

opportunities necessary to make informed health decisions.

The Ebola vaccine trial in Boende excluded a priori pregnant women,

putting women of childbearing potential in front of the choice between

pregnancy and participation in the trial. Our ndings suggest that

women strategically utilised the limited “decision space” they had in the

way that they believed served them best. They made pragmatic choices

based on their understanding of the trial’s one-to-two-year no-preg-

nancy requirement. This involved weighing their desire for children in

the next two years against potential trial benets. For some women of

M. Salloum et al.

Vaccine 55 (2025) 127000

5

6

6

7

7

8

8

1

/

8

100%