Original Research

A School- and Home-Based Intervention

to Improve Adolescents’ Physical Activity

and Healthy Eating: A Pilot Study

Lorraine B. Robbins, PhD, RN, FNP-BC, FAAN

1

, Jiying Ling, PhD, RN

1

,

Kimberly Clevenger, MS

2

, Vicki R. Voskuil, PhD, RN, CPNP

3

,

Elizabeth Wasilevich, PhD, MPH

1

, Jean M. Kerver, PhD, RD

4

,

Niko Kaciroti, PhD

5,6

, and Karin A. Pfeiffer, PhD

2

Abstract

This study evaluated feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a 12-week Guys/Girls Opt for Activities for Life (GOAL)

intervention on 10- to 13-year-old adolescents’ body mass index (BMI), percent body fat, physical activity (PA), diet quality, and

psychosocial perceptions related to PA and healthy eating. Parent–adolescent dyads from two schools were enrolled. Schools

were assigned to either GOAL (38 dyads) or control (43 dyads) condition. The intervention included an after-school club for

adolescents 2 days/week, parent–adolescent dyad meeting, and parent Facebook group. Intervention adolescents had greater

autonomous motivation for PA and self-efficacy for healthy eating than control adolescents (both p< .05). Although between-

group differences were not significant, close-to-moderate effect sizes resulted for accelerometer-measured moderate-to-

vigorous PA and diet quality measured via 24-hr dietary recall (d¼.46 and .44, respectively). A trivial effect size occurred

for percent body fat (d¼.10). No differences emerged for BMI. Efficacy testing with a larger sample may be warranted.

Keywords

diet, exercise, nutritional status, obesity, overweight, parent, social media, social support, school nursing

Health-promoting interventions are particularly needed for

underserved (minority and/or low income) adolescents in

urban areas who have a higher risk for becoming overweight

(OW) or obese (OB) due to greater barriers practicing a

healthy lifestyle compared to other adolescents (O’Haver,

Jacobson, Kelly, & Melnyk, 2014). Although schools are

an ideal setting for reaching at-risk adolescents (Nordin,

Solberg, & Parker, 2010) to promote physical activity

(PA) and improve diet quality, evidence remains insufficient

for determining the efficacy of school-based interventions,

particularly those that can be broadly disseminated, in

improving these behaviors among underserved adolescents,

especially for those who are Black, in order to reduce

the high OW/OB prevalence (Barr-Anderson, Singleton,

Cotwright, Floyd, & Affuso, 2014; Kornet-van der Aa,

Altenburg, van Randeraad-van der Zee, & Chinapaw,

2017). Although targeting schools is important for reaching

these at-risk adolescents (Nordin et al., 2010), some

researchers are recommending that school-based interven-

tions also extend into the home to actively involve parents/

guardians (further referred to as parents) to help underserved

young adolescents increase their PA and diet quality (D. K.

Wilson, Van Horn, et al., 2011).

Background

In a review of the literature, we found five school-based

studies that focused on improving body mass index (BMI)

and included young adolescents in economically disadvan-

taged communities. Only two of the five significantly

improved BMI and BMI z-score with small-to-moderate

1

College of Nursing, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

2

Department of Kinesiology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI,

USA

3

Nursing Department, Hope College, Holland, MI, USA

4

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Michigan State University,

East Lansing, MI, USA

5

Center for Human Growth and Development, University of Michigan,

Ann Arbor, MI, USA

6

Department of Biostatistics, Center for Computational Medicine and

Bioinformatics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Corresponding Author:

Lorraine B. Robbins, PhD, RN, FNP-BC, FAAN, College of Nursing,

Michigan State University, Bott Building for Nursing Education and

Research Room #C245, 1355 Bogue Street East Lansing, East Lansing, MI

48824, USA.

Email: [email protected]

The Journal of School Nursing

1-14

ªThe Author(s) 2018

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

DOI: 10.1177/1059840518791290

journals.sagepub.com/home/jsn

effect sizes ranging from 0.31 to 0.70 (Lazorick, Fang,

Hardison, & Crawford, 2015; Lubans, Morgan, Aguiar, &

Callister, 2011). The remaining three studies reported very

small effect sizes on BMI or BMI z-score ranging from

0.07 to 0.04 (Foster et al., 2008; Franckle et al., 2017;

Hollis et al., 2016). However, the two studies with signifi-

cant results had relatively smaller sample sizes than the

remaining three studies (N¼100, 362 vs. 1,150, 1,349,

219,762). Furthermore, one of the two studies, which was

conducted in the United States, did not include randomiza-

tion of the schools to intervention or control conditions and

provided US$20,000 dollars to each school for intervention-

related expenses; the other study, which was conducted out-

side the United States, involved boys only and did not blind

assessors to group assignment.

For the three studies that did not yield significant results,

intervention duration was 12 months in one (Hollis et al.,

2016) and 2 years in the remaining two studies (Foster et al.,

2008; Franckle et al., 2017), and parents were either not

involved or had minimal involvement (e.g., newsletters

about PA sent home; at school meetings, parents encouraged

to assist their children to engage in healthy behaviors). The

12-month intervention was theory based, but focused on PA

only; whereas the other two interventions were not theory

based and involved varied curricular and policy changes to

improve PA and diet quality.

For the two studies that had significant results, the inter-

ventions were theory based, focused on PA and diet quality,

andrangedindurationfrom14weeksto6months.Both

interventions had no parental involvement and included cur-

ricula delivered by teachers during the school day that

involved education, skill development (e.g., self-

monitoring, goal setting), and opportunities for PA. While

both studies demonstrated that school-based interventions

can be successful, altering the curricula during the school day

to promote PA and healthy eating may not be feasible in all

schools due to pressure perceived by administrators and

teachers to improve students’ academic performance (Beets

et al., 2016). Interventions that occur in conjunction with

schools, but take place after school, may be a necessary and

ideal solution for addressing these issues because most ado-

lescents attend school (D. K. Wilson, Van Horn, et al., 2011).

Although participation by adolescents in an after-school

program at their school to increase PA and healthy eating is

convenient and provides an opportunity for acquiring

knowledge and building skills, it may not be sufficient for

assisting them to adequately achieve both behavioral objec-

tives. Although active involvement of parents along with

their adolescents (Bradley et al., 2011) in interventions may

also be important, involving parents has been a challenge

(Smith, Wohlstetter, Kuzin, & De Pedro, 2011), indicating a

need to test novel approaches.

In a systematic review of PA and dietary mobile applica-

tions, Brannon and Cushing (2015) found that apps targeting

health promotion by focusing on improving both adolescent

PA and diet quality are sparse with limited incorporation of

strategies to strengthen theoretical constructs, such as social

support, that have already been identified as important pre-

dictors of positive behavior change. Another limitation is

that technology for promoting healthy behaviors is usually

designed for the individual who needs to change as opposed

to the one who can offer support for the process (Ferrer &

Ellis, 2017). Due to pervasive use among adults, social net-

working platforms, such as Facebook, may have the poten-

tial to address these limitations and bolster parents’ support

for their adolescents to make positive behavioral changes.

Despite the promise of this approach, we found no interven-

tion to empower parents via Facebook to assist their adoles-

cents with increasing PA and diet quality, indicating that the

capability of social networking for achieving this objective

remains basically untapped (Cavallo et al., 2014; Hammers-

ley, Jones, & Okely, 2016).

To address these issues, we conducted a pilot study to test

a 12-week, three-component Guys/Girls Opt for Activities

for Life (GOAL) intervention that involved parents via Face-

book, as an adjunct to a single parent–adolescent dyad meet-

ing and also an after-school club (2 days/week) for urban,

underserved adolescents. To our knowledge, no study

including an intervention combining these three components

has been conducted with parents and adolescents of low

socioeconomic and minority status. Based on this informa-

tion, the primary purpose of this study was 2-fold: (1) to

evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of our school- and

home-based intervention and (2) to examine the preliminary

efficacy of the intervention versus a control condition on

fifth- to seventh-grade adolescents’ accelerometer-

measured moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA);

diet quality; and psychosocial variables including motiva-

tion, self-efficacy, and perceived social support for PA and

healthy eating. A secondary aim was to explore any effect of

the intervention on adolescents’ percent body fat and BMI.

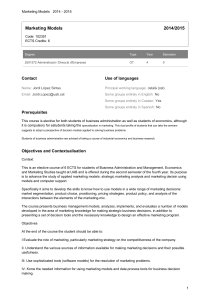

Theoretical Framework

The intervention was guided by self-determination theory

(SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000) and the information–motiva-

tion–behavioral skills (IMB) model (Fisher, Fisher, Bryan,

& Misovich, 2002). The SDT identifies the following three

basic needs that promote intrinsic motivation to drive beha-

vior: competence (self-efficacy), autonomy (choice), and

relatedness (social support). The IMB model indicates that

making a positive change in behavior is increased when an

individual has information, motivation, and behavioral skills

for accomplishing the task. Self-efficacy (Fitzgerald, Heary,

Kelly, Nixon, & Shevlin, 2013), social support from others

(e.g., parents, peers, and instructors or teachers; Glozah &

Pevalin, 2015; Lytle et al., 2009), and motivation (Dwyer

et al., 2017; Huffman, Wilson, Van Horn, & Pate, 2017)

are related to MVPA and healthy eating among adolescents.

All three components of GOAL were designed to increase

2The Journal of School Nursing XX(X)

the latter three modifiable psychosocial variables among

adolescents, including motivation, self-efficacy, and

perceived social support for PA and healthy eating (see

Figure 1; Table 1).

Method

Study Design

The Michigan State University Biomedical Institutional

Review Board approved the study, and administrators pro-

vided approval to conduct it in their respective schools. A

pretest–posttest quasi-experimental design was used. After

adolescents completed baseline data collection, a statistician

not involved in the study randomly assigned one of the two

kindergarten to eighth-grade public schools located in the

same low-socioeconomic status (SES), large urban school

district in the Midwestern United States to receive the

GOAL intervention. The remaining school served as a con-

trol condition with participants receiving usual activities that

were similar to those of the intervention school.

Recruitment

All adolescents in the selected academic grades were called

to an assembly at each school so researchers could describe

the study protocol and invite them to participate. Adoles-

cents were told that, after baseline data were collected, their

school would be randomly assigned by a statistician to

receive either GOAL or usual school activities, and then

they would be contacted to hear the randomization status

of their school. The researchers distributed a packet contain-

ing study information, consent, and assent forms, and a

screening tool to determine eligibility to all adolescents.

Researchers told adolescents to share the packet of informa-

tion with their parents and to return the packets, including

completed forms indicating whether they are interested in

participating or not, to researchers present at their school

during the next 2 days. Researchers informed adolescents

that written parental consent and adolescent assent would

be required prior to participation.

Participants and Setting

Participants were included if they were 10–13 years of age;

in fifth to seventh grade; able to read, understand, and

speak English; agree to random assignment; available to

participate in GOAL, including after-school program 2

days/week, if offered at their school; and able to identify

one parent who is willing and able to serve as a support

person by (a) assisting the adolescent to attain adequate PA

and eat healthy, (b) participating with the adolescent in one

face-to-face meeting occurring during the first intervention

week, and (c) completing weekly healthy habit-forming

tasks to help the adolescent increase PA and healthy eating

and posting in a private Facebook group. Participants were

excluded if they had a mental or physical health condition

precluding safe participation or were involved in school or

community sports or other organized programs (e.g., dance

lessons) that involved MVPA and required participation

after school 4 or more days per week during the school

year. Thirty-nine adolescents and 38 parents in the inter-

vention school and 45 adolescents and 43 parents from the

control school enrolled (N¼81 dyads total). One twin in

each of three families was randomly selected for inclusion

in data analysis. A median sample size of 30 per group is

adequate for a pilot study (Billingham, Whitehead, &

Julious, 2013). With regard to overall student enrollment

in the selected grades in each school (n¼115 intervention,

n¼173 control), compared to the control school, the inter-

vention school had a lower percentage of female (59.5%vs.

41.7%), White (18.5%vs. 13.9%), and Hispanic students

(19.1%vs. 12.2%), and a higher percentage of Black

(41.0%vs. 62.6%) and disadvantaged students (66.5%vs.

75.7%; Michigan’s Center for Educational Performance

and Information, 2018). Figure 2 depicts the flow diagram

of participants.

Measures

Demographics. Each parent responded to survey questions

about the parent’s and adolescent’s age, sex, and race/ethni-

city; parent’s marital status and SES (employment,

Proximal

Outcomes

•Minutes of MVPA

(accelerometer-

measured)

•Diet quality

Distal

Outcomes

•BMI

•% body

fat

Demographics

•Age, sex,

race/ethnicity,

academic grade,

SES

Intervention - Information, Motivational Messages, & Behavioral

(IMB Model) Strategies underpinning the following 3 intervention

components delivered to increase three modifiable psychosocial

variables, including adolescents’ Self-Efficacy, Social Support,

and Motivation (SDT: Competence, Relatedness, & Autonomy):

1) After-school GOAL Club, including MVPA

& healthy eating and cooking skill development (targeting self-

efficacy, social support, and motivation)

2) Parent-adolescent dyad meeting (targeting self-efficacy, social

support, and motivation)

3) GOAL social networking app for parents (with their adolescent;

targeting self-efficacy, social support, and motivation)

Figure 1. Theoretical framework.

Robbins et al. 3

educational level, and annual family income); and adoles-

cent’s academic grade.

Minutes of MVPA. Minutes of MVPA were assessed via

ActiGraph GT3Xþ(Version 3.2.1), a triaxial acceler-

ometer (http://www.theactigraph.com) that is reliable and

valid for assessing MVPA (Ha¨nggi, Phillips, & Rowlands,

2013). Monitors were worn at the hip on an elastic belt and

were set to begin data collection at 5 a.m. on the day after

monitors were given to adolescents at school. To remind

adolescents to wear it (Trost, McIver, & Pate, 2005), each

received a text message (and/or phone call at home if

preferred) every morning. Monitors were returned to

school after the seventh day of data collection (Trost, Pate,

Freedson, Sallis, & Taylor, 2000). Data were collected in

raw mode and reintegrated into 15-s epochs (Evenson,

Catellier, Gill, Ondrak, & McMurray, 2008). The follow-

ingsegmentsofthedaywhenmost participants would be

asleep or not wearing their monitor were filtered out: 9

p.m.to7a.m.onweekdaysand9p.m.to11a.m.on

weekends (Catellier et al., 2005). Nonwear time (defined

as periods with at least 60 consecutive zeros) was

removed, allowing for 2-min disruptions up to 100

counts/min (Troiano et al., 2008). Participants with at least

480 min/day of wear time on at least 3 days, including 1

weekend day, were included in subsequent analysis

(Penpraze et al., 2006). Age appropriate cut points were

used to identify mean minutes per hour of MVPA via

ActiLife 6 (Version 6.13.2) software. MVPA was classi-

fied as 574 counts/15 s (Evenson et al., 2008).

Diet quality. At baseline and postintervention, adolescents

completed the web-based Automated Self-Administered

24-Hour (ASA24) Dietary Assessment Tool, which is

reported to be valid for 24-hr dietary recall (Subar et al.,

2012; Thompson et al., 2015). Using a laptop computer at

each time period, adolescents individually reported their

dietary intake for the previous day. Data with caloric intake

less than 600 kcal/day were removed (Automated Self-

Administered 24-Hour Dietary Assessment Tool: Reviewing

and Cleaning ASA24

®

Data, 2017). Based on the ASA24

results, a Healthy Eating Index (Guenther et al., 2014) was

computed (possible scores 0–100), indicating the degree to

which an individual meets dietary guidelines. Fruit intake

was scored from 0 (no fruit)to5(0.4 cup equivalents/

1,000 kcal) and vegetable intake was scored from 0 (no

vegetables)to5(1.1 cup equivalents/1,000 kcal).

BMI and percent body fat. Two research assistants (RAs)

measured each adolescent’s height and weight behind a pri-

vacy screen at school. Height without shoes was measured to

the nearest 0.10 cm with a Shorr Board (Weigh and Measure,

Table 1. Description of the Three Intervention Components and Weeks of Delivery.

Weeks Intervention Components

1Parent–Adolescent Dyad Meeting (120 min) conducted at adolescents’ school to assist parents in supporting adolescents’ MVPA and

healthy eating included:

Discussion of information, behavioral strategies to assist parents in helping their adolescent increase healthy eating and PA

Chef conducted healthy eating and cooking session and distributed bag of groceries to facilitate preparation of the

demonstrated recipe by dyads at home

2–12 After-school GOAL Club began for adolescents, including PA and healthy eating and cooking skill building (18 events; 2 days/week; not

offered during winter/spring school breaks or no-school days)

50-min PA session included:

5-min discussion of the week’s PA theme plus information and behavioral strategies that parents were receiving via

Facebook, followed by a motivational message;

5 min of warm-up/stretching;

20 min of sport skill building;

15 min of fun games or game to apply learned sports skills; and

5 min of cooldown/stretching.

50-min “hands on” healthy eating and cooking skill-building session included:

5-min discussion of the week’s healthy eating and cooking theme plus information and behavioral strategies that parents

are receiving via Facebook, followed by a motivational message

45 min involving small groups working at mobile kitchens to prepare a healthy beverage, snack, or meal and then sample

what they prepared

Facebook Participation included the following weekly healthy eating and PA habit-forming tasks to assist parents in helping their

adolescents with MVPA and healthy eating and cooking:

Post a comment or picture about the healthy recipe you selected to make with your adolescent or about a strategy that

you used to help your adolescent eat healthy

Post a comment or picture about the PA that you helped your adolescent engage in or a strategy that you used to help your

adolescent get PA

Note. MVPA ¼moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; PA ¼physical activity; GOAL ¼guys/girls opt for activities for life.

4The Journal of School Nursing XX(X)

LLC, Olney, MD). RAs asked adolescents as needed to

remove hair accessories or change hairstyles. If an adoles-

cent refused, RAs obtained the measurement but also mea-

sured hairdo height (using a small plastic ruler) and recorded

all information on the data collection form. With the ado-

lescent in light clothing and no shoes, weight in kilograms to

nearest 0.10 kg and percent body fat to the nearest 0.1%

were measured using a Foot-to-Foot Bioelectric Impedance

Scale (Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Two measure-

ments were taken for height, weight, and percent body fat.

If differences between the two measurements were 0.5 cm

for height, 0.5 kg for weight, or 0.5%for percent body

fat, a third was taken. The two closest measures were

recorded on the data collection form and averaged. Adoles-

cent BMI for age and sex was determined using the online

SAS program for Centers for Disease Control and Preven-

tion (2015) Growth Charts. Healthy weight was defined as

<85th percentile, while OW/OB was defined as 85th per-

centile. Validity in percent body fat via bioelectric impe-

dance for adolescents has been demonstrated by

comparisons to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Barreira,

Staiano, & Katzmarzyk, 2013), the latter of which is not

feasible in schools.

At baseline, parents were invited to their respective

schools for height and weight measures. The procedure

was similar to the one employed for adolescents. BMI

Enrollment

Randomized schools to Intervention and Control conditions

Analyzed (n=34 adolescents)

•Excluded 1 adolescent from analysis

due to 1 parent/guardian having twins

(1 adolescent twin randomly selected

for inclusion in analysis)

Analyzed (n=43 adolescents)

•Excluded 2 adolescents from analysis

due to 2 parents/guardians having twins

(1 adolescent twin from each family

randomly selected for inclusion in

analysis)

Analysis

Of 288 enrolled students, 252 (87.5%) present at schools during time of recruitment received study enrollment packets.

school 1 (n=101 received packets of 115 enrolled students)

school 2 (n=151 received packets of 173 enrolled students)

Returned Packets (n=163)

school 1 (n=67)

school 2 (n=96)

Enrolled

school 1 (n=39 adolescents; 38 parents/guardians)

school 2 (n=45 adolescents; 43 parents/guardians )

Baseline Data Collection

school 1 (n=39 adolescents; 38 parents/guardians)

school 2 (n=45 adolescents; 43 parents/guardians)

• Declined (n=22 in school 1; n=43

in school 2)

• Excluded - not meeting

inclusion/exclusion criteria (n=1 in

school 1; n=8 in school 2)

• Unable to participate - personal

reasons (n=5 in school 1; 0 in

school 2)

Allocated to intervention (n=39 adolescents;

n=38 parents/guardians)

Allocated to control (n= 45 adolescents; n=43

parents/guardians)

Allocation

Lost to follow-up (n=4 adolescents [2

relocated; 1 refused; 1 removed for

misbehavior]); n=35 adolescents

completed post-intervention measures

Lost to follow-up (n=0 adolescents);

n=45 adolescents completed post-

intervention measures

Post-Intervention

Figure 2. Participant flow diagram.

Robbins et al. 5

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

1

/

14

100%