1

REVIEW PAPER

Tourism and climate change: a review of threats and adaptation strategies for Africa

Gijsbert Hoogendoorna* and Jennifer M. Fitchettb

a Department of Geography, Environmental Management and Energy Studies, University of

Johannesburg, P.O. Box, 524, Auckland Park, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2006; email:

[email protected] b Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand,

Private Bag x3, Wits, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2050; email:

Funding

This work was conducted while JF was employed as a postdoctoral fellow funded by the

DST/NRF Centre of Excellence for Palaeosciences.

2

REVIEW PAPER

Tourism and climate change: a review of threats and adaptation strategies for Africa

Abstract

The intersection of tourism and climate change has seen significant research over the past

two decades, focusing particularly on issues of mitigation and adaptation in the global

North. Research output has predominantly been centred on the Mediterranean and Nordic

countries and number of localities in North-America. The global South has seen

significantly less investigation, despite having significantly lower adaptive capacity to the

impacts of climate change, and numerous countries with rapidly growing tourism sectors.

The African continent specifically has seen appreciably less research than other countries

in the global South, despite arguably having the lowest adaptive capacity and projections of

severe impacts of climate change to the tourism sector from temperature increases, changes

in precipitation volume and sea level rise. This paper therefore presents a review of the

existing literature on adaptation strategies of tourism sectors and participants in African

countries. The crucial argument of this paper is in highlighting the need for an increase in

research into the threats of climate change to tourism in African countries, identifying

future research trajectories. The development of such knowledge would assist in the

development of adaptation and mitigation strategies for these most vulnerable tourism

economies.

Keywords: tourism; climate change; Africa; adaptation; future research.

3

1. Introduction

Climate affects the seasonality of tourism, tourists’ selection of destinations, available tourist

activities and attractions, and the overall satisfaction of a vacation (Becken, 2005; Gössling,

Scott, Hall, Ceron & Dubois, 2012; Kyriakidis & Felton, 2008; Morabito, Crisci, Barcaioli &

Maracchi, 2004; Richins & Scarinci, 2009). Climate change, therefore, has the potential to

reduce the sustainability and long-tern viability of global tourism. As climate plays a

significant role in the comparative selection of a tourist destination, climate change has the

potential to alter the popularity of tourism localities and regions (Rosselló & Waqas, 2015).

Furthermore, progressive changes in the climate of a location and increasing threats of

associated natural hazards including storms, flooding and sea-level rise, can result in

destinations becoming progressively unsuitable for tourism (C. Rogerson, 2016). The ability

of tourism destinations to mitigate and adapt to climate change is hampered by the competing

requirements of the more immediate development of a destination’s tourism sector and

infrastructure (Mohan & Morton, 2009). Long-term planning for the consequences of climate

change is often believed to be unnecessary due to the delay until such affects are experienced,

and the probability of them occurring (Hoogendoorn, Grant & Fitchett, 2016). While for

developed countries it could be argued that the threats and opportunities to tourism of climate

change may be relatively well balanced (Perch-Nielsen, Amelung & Knutti, 2010), the

competing challenges of economic development and social uplift in the developing countries

of the African continent result in a lowered adaptive capacity such that threats to the tourism

sector are the most likely, and a highly critical, outcome of climate change (C. Rogerson,

2016).

Kaján and Saarinen’s (2013) review in Current Issues in Tourism explores major global

issues around tourism, climate change and adaptation which emphasises the need for

community specific studies. However, we would argue that despite the significant

contribution by Kaján and Saarinen (2013), the relationships between climate change and

tourism are complex, inter-related and often location specific. The threats of climate change

to tourism, are heightened in developing countries (C. Rogerson, 2016). Therefore, this

review paper critically explores the scant existing literature on tourism and climate change

for the African continent, and argues for a greater research focus on the continent to improve

the understanding of these relationships and to facilitate improved adaptation strategies. This

is particularly true for countries, which have additional immediate policy and developmental

4

concerns. The lack of available capital, proactive policies, and expert knowledge on climate

change reduces the adaptive capacity of developing countries, and in turn their tourism

sectors. Moreover, this paper highlights the shortage of academic research on climate change

and tourism in Africa (Njoroge, 2015), and points towards future research trajectories. The

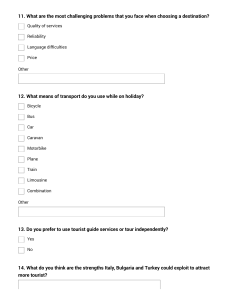

themes discussed in this paper are the climate change threats to tourism relating to increasing

temperatures, precipitation changes, sea level rise, increased concentration of pollution,

followed by a discussion of the findings of location-, attraction-, and severity-dependant

adaptation requirements. These themes were identified by the authors during the analysis of

existing literature as those which pose the most critical threats to tourism, and which have

seen preliminary investigation but requires deeper research focus due to the severity of

projected future impacts. In terms of literature consulted, the authors conducted a wide-

ranging search, cross checked through Google Scholar, Science Direct, Ebscohost, Springer

and Web of Knowledge, across any disciplines that specifically made reference to climate

change and tourism in Africa. No time period was specified during searches given the paucity

of research. A number of key words and phrases were used in this study, too numerous to

mention here, but some of the key ones were ‘climate change + tourism + Africa’, ‘climate

threats to tourism in Africa’, ‘global environmental change + tourism + Africa’. As well as

the key words ‘climate change + tourism’ with each of the 54 African countries entered

separately.

2. The relationship between global climate change and tourism

Globally, tourism is one of the fastest growing global economic sectors, contributing

considerably to the national and local economies of countries around the world (Scott &

Lemieux, 2010). Weather and climate are important determinants of the success of tourism in

a given location, and arguably the predominant factor controlling tourist flows on a global

scale (Moreno, 2010; Scott and Lemieux, 2010). Despite the important role of climate on

tourism activities, research into the relationship between climate and tourism has evolved

relatively recently, emerging only in recent decades (March, Sauri & Llurdes, 2014; Scott,

McBoyle & Schwartzentruber, 2004). This research highlights recognition by state

governments and tourism stakeholders that climate change threatens to significantly

detriment tourism (Hamilton, Maddison & Tol, 2005; Moreno, 2010).

5

Climate change impacts on tourism are already being observed, and are gradually influencing

decision-making within the tourism sector (Simpson, Gössling, Scott, Hall & Gladin, 2008).

The United World Tourism Organisation (UNTWO) has identified climate change impacts on

tourist destinations, their competitiveness and sustainability (UNWTO, UNEP & WTO,

2008). The redistribution of climatic resources between different tourism destinations is of

particular concern (Ehmer and Heymann, 2008; N. Marshall, P. Marshall, Abdulla, Rouphael

& Ali, 2011). Due to the changes in the length and quality of climate-dependent tourism

seasons, the competitive advantage of certain destinations will be altered, ultimately affecting

the viability of tourism businesses globally (UNWTO, 2009). The indirect impacts of climate

change include changes to a destination’s environment in response to the altered climate

(Agnew and Viner, 2001). These environmental changes can include changes in the local

biodiversity, landscape aesthetics, a decrease in wildlife, increased coastal erosion, and

damage to tourism infrastructure (Agnew & Viner, 2001; Reddy, 2012).

The combined direct and indirect impacts of climate change will have significant

ramifications on tourism destinations, businesses and infrastructure (March et al., 2014;

Simpson et al., 2008). The effects of climate change on the tourism sector will vary

significantly based on the type of tourism market and the geographic region of a tourist

destination (Simpson et al., 2008). The threats of climate change on winter tourism,

specifically on skiing destinations, includes reductions in the depth of snow and in the

duration of the winter season (c.f. Harrison, Winterbottom & Johnson, 2001; Scott, McBoyle

& Mills, 2003; Whetton, Haylock & Galloway, 1996). Beach tourism faces threats of

intolerably high temperatures, more frequent precipitation, changes in wave dynamics and sea

level rise (Ehmer and Heymann, 2008; Fitchett, Grant & Hoogendoorn, 2016; Moreno and

Amelung, 2009; Sagoe-Addy & Addo, 2013). Mediterranean regions, in particular, are

projected to experience hotter climatic conditions which may result in significant discomfort

for tourists during peak summer tourist period (Amelung et al., 2007). By contrast, the

warming trend projected for countries in northern Europe is likely to be beneficial to tourism,

as it will result in a more ameliorable climate better suited to outdoor activities (Amelung et

al., 2007). The geography of a particular location, the nature of the tourist attractions, and the

regionally-specific climate change projections for different temporal periods are thus of vital

importance.

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

1

/

28

100%