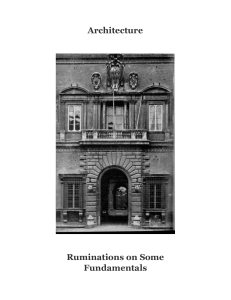

Architecture

Ruminations on Some

Fundamentals

Architecture

One of the chapters of Le Corbusier’s seminal work ‘Vers Une

Architecture’ is entitled ‘Architecture, Pure Creation of the Mind’.

Many, have perhaps interpreted this statement as a support for the

idea that ‘anything goes’ in architecture, particularly in a time

when technology allows almost limitless possibilities in this regard.

What Le Corbusier actually said on the subject is as follows:

‘You employ stone, wood and concrete, and with these materials you build houses

and palaces; that is construction. Ingenuity is at work.

But suddenly you touch my heart, you do me good, I am happy and I say : “This is

beautiful”. That is Architecture. Art enters in.

My house is practical. I thank you, as I might thank Railway engineers or the

telephone service. You have not touched my heart.

But suppose that walls rise towards heaven in such a way that I am moved. I perceive

your intentions. Your mood has been gentle, brutal, charming or noble. The stones

you have erected tell me so. You fix me to the place and my eyes regard it. They

behold something which expresses a thought. A thought which reveals itself without

word or sound, but solely by means of shapes which stand in a certain relationship to

one another. These shapes are such that they are clearly revealed in light. The

relationships between them have not necessarily any reference to what is practical or

descriptive. They are a mathematical creation of your mind. They are the language

of Architecture. By use of inert materials and starting from conditions more or less

utilitarian, you have established certain relationships which have aroused my

emotions. This is Architecture.’

Pevsner was of course paraphrasing this when he said:

‘A BICYCLE shed is a building. Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture’

What is curious about both quotes however, is the extent to which

they seem to take for granted the architect’s ability to fulfil the

utilitarian demands of ‘shelter’. Well, since the time ‘Vers Une..’

the world has experienced roughly 80 years of cold, leaky,

overheated and ‘badly maintained’ (for which we should really read

badly designed) modernist (Corb’s creations included) and varying

hues of Post-Modernist buildings that would suggest the faith

placed by Pevsner and Corb in the architect’s practical abilities has

perhaps more often than not been misplaced.

This reminds us that in fact ‘the practical house’, for which Corb

would thank his architect as he thanked a railway engineers has

throughout history been the building type that architect have had

least to do with. More often than not, such houses have been

planned and built by the simple people who lived in them with

succeeding generations learning from their forefathers by osmosis.

Today, the existence of specialist house builders continues this

separation between architects and mass housing (after a brief and

disastrous attempt at bringing them together in the 60’s and 70’s)

Figure 1. Park Hill Flats, Sheffield, 1961.

The higher building types; Palaces, temples, art galleries and the

like, have always been a different matter. In Ancient Egypt, the

high priest was responsible for the planning and erection of such

structures for which the inherent ability to inspire awe, love, hope

and fear was perhaps more important than the kinds of utilitarian

concerns mentioned earlier. The rain and sun of course had to be

kept out, but craftsman would see to that rather than the high

priest. It’s easy to see how the high priest eventually became the

architect. The thing about a high priest of course, is that he can tell

you what is good architecture and what isn’t, and you have to

listen!

Figure 2. Ancient Egyptian Temple at Karnak.

But, as I sit here 4 months unemployed having recently qualified

after 13 yrs of hard slog (almost twice the length of time it takes to

become a GP), I can tell you that there are far too many architects

in the market today to justify having ‘temple or palace design’ as

the be all and end all of your skill-set. The replacement of skilled

craftsmen by ‘operatives’ in conjunction with the practicable

measurable outcomes that the’ sustainability agenda’ demands of

modern building practice has also meant that architects have in

recent years had to learn the art of the practical and the utilitarian,

and the rise of real proficiency in this area is to my mind very

recent, emerging, with few exceptions from that generation of

architects, at least in the UK, who were training during the fall out

from the ill-fated housing experiments of the 60’s and 70’s.

Jonathan Sergison and Stephen Bates were both born in 1964,

which means they were 20 yrs old when Prince Charles made his

famous ‘Carbuncle’ speech to the RIBA. At the turn of the 21st

Century, about 70 yrs after Corb had talked about it, Sergison

Bates architects produced a series of designs for mass housing that

you could thank them for as you would thank a railway engineer.

Figure 3. Sergison Bates unbuilt entry for the 2001 Circle 33 Innovation in Housing competition,

Bow east London.

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

38

38

39

39

40

40

1

/

40

100%