Cardiac Surgery Site Infections: Epidemiology & Prevention

Telechargé par

rabiakhouildi

Please

cite

this

article

in

press

as:

Lepelletier

D,

et

al.

Epidemiology

and

prevention

of

surgical

site

infections

after

cardiac

surgery.

Med

Mal

Infect

(2013),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.003

ARTICLE IN PRESS

+Model

MEDMAL-3432;

No.

of

Pages

7

Disponible

en

ligne

sur

www.sciencedirect.com

Médecine

et

maladies

infectieuses

xxx

(2013)

xxx–xxx

General

review

Epidemiology

and

prevention

of

surgical

site

infections

after

cardiac

surgery

Épidémiologie

et

prévention

des

infections

du

site

opératoire

après

chirurgie

cardiaque

D.

Lepelletier a,∗,d,

C.

Bourigault a,

J.C.

Roussel b,

C.

Lasserre a,

B.

Leclère a,

S.

Corvec a,d,

S.

Pattier b,

T.

Lepoivre e,

O.

Baron b,c,

P.

Despins b,c

aService

de

bactériologie

et

d’hygiène

hospitalière,

unité

de

gestion

du

risque

infectieux,

CHU

de

Nantes,

bâtiment

Le

Tourville,

5,

rue

du

Pr-Yves-Boquien,

44093

Nantes

cedex

01,

France

bService

de

chirurgie

thoracique

et

cardiovasculaire,

CHU

de

Nantes,

44000

Nantes,

France

cInserm

UMR

S

1087,

université

de

Nantes,

institut

du

thorax,

44000

Nantes,

France

dUFR

médecine,

université

de

Nantes,

EA

3826,

Nantes,

France

eDépartement

d’anesthésie-réanimation,

44000

Nantes,

France

Received

14

September

2012;

received

in

revised

form

20

June

2013;

accepted

19

July

2013

Abstract

Deep

sternal

wound

infection

is

the

major

infectious

complication

in

patients

undergoing

cardiac

surgery,

associated

with

a

high

morbidity

and

mortality

rate,

and

a

longer

hospital

stay.

The

most

common

causative

pathogen

involved

is

Staphylococcus

spp.

The

management

of

post

sternotomy

mediastinitis

associates

surgical

revision

and

antimicrobial

therapy

with

bactericidal

activity

in

blood,

soft

tissues,

and

the

sternum.

The

pre-,

per-,

and

postoperative

prevention

strategies

associate

controlling

the

patient’s

risk

factors

(diabetes,

obesity,

respiratory

insufficiency),

preparing

the

patient’s

skin

(body

hair,

preoperative

showering,

operating

site

antiseptic

treatment),

antimicrobial

prophylaxis,

environmental

control

of

the

operating

room

and

medical

devices,

indications

and

adequacy

of

surgical

techniques.

Recently

published

scientific

data

prove

the

significant

impact

of

decolonization

in

patients

carrying

nasal

Staphylococcus

aureus,

on

surgical

site

infection

rate,

after

cardiac

surgery.

©

2013

Elsevier

Masson

SAS.

All

rights

reserved.

Keywords:

Cardiac

surgery;

Surgical

site

infection;

Risk

factors;

Prevention

Résumé

Les

infections

du

site

opératoires

profondes

représentent

la

complication

infectieuse

majeure

de

la

chirurgie

cardiaque.

Essentiellement

staphy-

lococciques,

elles

nécessitent

une

reprise

chirurgicale

précoce

et

une

antibiothérapie

rapidement

bactéricide

au

niveau

du

sang,

des

tissus

mous

et

du

sternum.

Leurs

conséquences

sont

sévères

en

termes

de

morbidité

et

d’allongement

de

la

durée

de

séjour

hospitalier.

Les

stratégies

de

prévention

pré,

per-

et

postopératoire

associent

le

contrôle

des

facteurs

liés

aux

patients

(obésité,

diabète,

insuffisance

respiratoire),

la

préparation

cutanée

corporelle

(traitement

des

pilosités,

douche

préopératoire,

antisepsie

du

site

opératoire),

l’antibioprophylaxie,

la

maîtrise

de

l’environnement

du

bloc

opératoire

et

des

dispositifs

médicaux

mais

aussi

les

indications

et

la

qualité

des

techniques

opératoires.

Les

données

récentes

de

la

littérature

scientifique

montrent

un

impact

significatif

de

la

décolonisation

des

patients

porteurs

de

staphylocoques

doré

au

niveau

nasal

sur

le

taux

d’infection

du

site

opératoire

après

chirurgie

cardiaque.

©

2013

Elsevier

Masson

SAS.

Tous

droits

réservés.

Mots

clés

:

Chirurgie

cardiaque

;

Infection

du

site

opératoire

;

Facteurs

de

risque

;

Prévention

∗Corresponding

author.

E-mail

address:

didier[email protected]

(D.

Lepelletier).

1.

Introduction

More

than

40,000

cardiac

surgery

procedures

are

performed

every

year

in

France.

Deep

sternal

wound

infection

(mediastini-

tis)

is

the

most

severe

complication

and

surgical

site

infection

0399-077X/$

–

see

front

matter

©

2013

Elsevier

Masson

SAS.

All

rights

reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.003

Please

cite

this

article

in

press

as:

Lepelletier

D,

et

al.

Epidemiology

and

prevention

of

surgical

site

infections

after

cardiac

surgery.

Med

Mal

Infect

(2013),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.003

ARTICLE IN PRESS

+Model

MEDMAL-3432;

No.

of

Pages

7

2

D.

Lepelletier

et

al.

/

Médecine

et

maladies

infectieuses

xxx

(2013)

xxx–xxx

(SSI)

in

cardiac

surgery

performed

mainly

by

median

ster-

notomy

[1].

Its

incidence

is

relatively

low

and

has

remained

for

several

years,

but

it

concerns

4000

to

8000

increasingly

fragile

patients

every

year,

whose

risk

of

mortality

is

increased

from

10

to

40%

[2–4].

All

cardiac

surgery

units

in

France

are

concerned

by

the

occurrence

of

mediastinitis

and

confronted

to

its

severity

at

short

or

long

term,

to

its

difficult

management,

and

to

significant

over-cost

[5].

The

surgical

teams

in

these

units

have

developed

SSI

prevention

strategies

in

collaboration

with

hygienists,

anesthesiologists,

and

critical

care

specialists,

based

on

recent

recommendations,

particularly

those

concerning

antibiotic

prophylaxis

[6]

and

patient

preparation

[7].

Besides

these

recommendations,

choosing

preventive

measures

relies

on

the

knowledge

and

management

of

risk

factors

related

to

patients,

to

the

surgery,

and

to

the

operating

room

environment

[8].

The

prognosis

depends

on

the

delay

before

diagnosis

and

treatment,

on

the

therapeutic

method,

and

on

the

effectiveness

of

antibiotherapy.

The

definition,

the

incidence,

and

the

risk

fac-

tors

for

SSI

after

cardiac

surgery

are

presented

in

this

review.

We

have

summarized

the

main

strategic

orientations

currently

recommended

for

the

prevention

of

these

sometimes

devastating

infectious

complications.

2.

Definition

and

classification

of

surgical

site

infection

after

cardiac

surgery

SSI

include

superficial

infections

of

the

postoperative

scar

and

deep

wound

infections

such

as

sternal

osteitis,

mediastini-

tis,

and

endocarditis.

The

definitions

of

postoperative

SSI

are

adapted

from

those

issued

by

the

National

Technical

Committee

on

Nosocomial

Infections

and

Care

Related

Infections

(French

acronym

CTINILS

2007)

[9],

which

had

been

adapted

from

those

issued

by

the

centers

for

disease

control

and

prevention

(CDC)

[10].

2.1.

Superficial

wound

infections

Superficial

wound

infections

concern

the

skin

and

subcuta-

neous

tissue.

The

signs

(redness,

fluid

collection,

disunion)

are

always

local.

The

sternum

is

not

involved,

stable,

and

painless

on

bi-manual

palpation.

Most

of

the

time,

it

requires

only

local

(disinfection,

warm

pads)

and

oral

(antibiotics)

treatment.

But

it

may

extend

to

deeper

layers

at

any

time.

2.2.

Deep

infection

Deep

infection

includes

the

previously

mentioned

lesions

and

is

defined

by

the

involvement

of

tissue

below

the

subcutaneous

layer

with

at

least

one

of

the

following

criteria:

•

positive

culture

of

tissue

samples

or

mediastinal

fluid;

•

typical

presentation

of

mediastinitis

on

revision

surgery

or

anatomopathological

examination;

•

presence

of

one

of

the

following

elements:

fever

superior

to

38 ◦C,

thoracic

pain

or

sternal

instability,

with

either

pus

in

the

mediastinum,

or

positive

culture

of

peroperative

samples

or

of

hemoculture

(or

both

in

case

of

germs

commensal

of

the

cutaneous

flora).

Only

surgical

exploration

can

document

the

true

nature,

the

extent,

and

the

prognosis

of

infection.

Despite

the

helpfulness

of

these

definitions,

the

use

of

dif-

ferent

terms

to

define

SSI

may

account

for

the

difficulty

to

clearly

define

and

measure

its

incidence

[11].

Sternal

wound

complications

range

from

sterile

dehiscence

to

suppurative

mediastinitis,

and

the

terms

of

sternitis

or

sternal

osteitis

(surgi-

cal

revision

without

sternal

opening)

and

mediastinitis

(surgical

revision

with

sternal

opening)

are

used

to

define

deep

infection.

Some

definitions

published

in

the

2000s

are

author

specific

such

as

El

Oakley’s

or

Gardlund’s

[12,13].

Furthermore,

the

repro-

ducibility

of

SSI

diagnosis

may

vary

according

to

the

depth

of

infection

[11,14];

the

medical

specialty

of

the

physician

also

has

an

impact

(surgeon,

anesthesiologist,

infectious

dis-

ease

specialist,

bacteriologist,

hygienist),

stressing

the

need

for

a

multidisciplinary

approach

[14].

3.

Incidence

of

surgical

site

infection

in

cardiac

surgery

The

rate

of

SSI

varies

according

to

the

quality

of

the

local

epidemiological

surveillance

[15]

or

of

surveillance

networks,

of

the

SSI

definition

used

(superficial,

deep),

of

the

patient’s

profile,

and

of

the

type

surgical

procedure

[16,17].

The

true

global

incidence

of

infection

in

cardiac

surgery

is

thus

difficult

to

assess.

In

France,

the

alert,

investigation,

and

surveillance

of

nosocomial

infections

(French

acronym

RAISIN)

network

data

concerning

cardiac

surgery

is

made

on

too

small

samples

to

be

representative

[16].

According

to

some

authors

and

to

simplify

data

collection,

the

surveillance

of

patients

reviewed

surgically

(with

or

without

sternal

re-opening)

from

the

operating

room

and

onward,

would

allow

measuring

reliably

and

easily

the

incidence

of

deep

SSI

[3].

The

incidence

of

mediastinitis

after

the

1990s

has

not

decreased

compared

to

the

1970–1980s,

ranging

between

0.5%

and

4.4%

[18].

Various

scores

have

been

built

and

used

to

stratify

the

incidence

of

postoperative

SSI

according

to

risk

fac-

tors.

The

American

score

of

the

National

Nosocomial

Infections

Surveillance

(NNIS)

System

integrates

the

ASA

physical

status

score,

the

Altemeier

contamination

classification,

and

the

length

of

surgery

[19].

Other

scores

have

been

proposed

for

predic-

tion

based

on

factors

more

specifically

associated

to

the

risk

of

mediastinitis

identified

by

comparatives

studies

in

multivariate

analysis

[20–22].

4.

Physiopathology

of

surgical

site

infection

after

cardiac

surgery

The

contamination

of

the

operative

site

may

be

due

to

the

patient’s

endogenous

flora

or

to

the

surgical

team’s

or

operating

room

exogenous

flora,

and

is

often

peri-operative.

Some

factors

promote

the

occurrence

of

SSI

from

this

contamination,

such

as

tissue

necrosis,

hematoma,

foreign

body,

of

a

prosthesis

or

of

an

implant,

and

bad

vascularization.

Please

cite

this

article

in

press

as:

Lepelletier

D,

et

al.

Epidemiology

and

prevention

of

surgical

site

infections

after

cardiac

surgery.

Med

Mal

Infect

(2013),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.003

ARTICLE IN PRESS

+Model

MEDMAL-3432;

No.

of

Pages

7

D.

Lepelletier

et

al.

/

Médecine

et

maladies

infectieuses

xxx

(2013)

xxx–xxx

3

4.1.

The

impact

of

endogenous

flora

The

impact

of

endogenous

flora

is

essential

in

the

phys-

iopathology

of

SSI.

Since

the

late

1990s

it

was

acknowledged

that

nasal

colonization

by

Staphylococcus

aureus

was

a

risk

fac-

tor

for

S.

aureus

SSI

after

cardiac

surgery

[23,24]

with

a

great

similitude

of

colonization

and

infection

strains.

4.2.

The

exogenous

contamination

The

exogenous

contamination

of

the

operative

site

is

either

handborne

or

airborne.

The

airborne

contamination

requires

two

associated

phenomena,

the

presence

of

microorganisms

(air

bio-

contamination)

and

of

inert

particles

(air

contamination)

some

of

which

are

used

as

support

by

bacteria.

The

microorganisms

often

come

from

the

usual

saprophyte

flora

of

air

(rarely

pathogenic)

and

from

the

commensal

human

flora

(mostly

S.

aureus,

coagu-

lase

negative

staphylococci,

sometimes

Gram-negative

bacteria)

released

by

human

bodies

(patients

and

surgical

team)

[8,25].

The

particles

are

released

by

individuals

(cutaneous

squamous

cells,

skin

appendages,

respiratory

droplets,

and

droplet

nuclei),

and

textiles

(surgical

team’s

clothes

and

operative

field

drapes);

the

quantity

is

proportional

to

the

number

of

individuals

present

in

the

room

and

to

their

movements

and

moving

around,

as

well

as

to

the

quality

of

textiles

used

(no-woven

and

polycoton

drapes

emit

less

particles

than

cotton

drapes

and

more

parti-

cle

proof)

[26].

The

surgical

team’s

flora

is

rarely

the

cause.

Contamination

by

soiled

material,

very

rare,

has

now

become

exceptionally

rare

because

of

the

recent

strengthening

of

steril-

ization

and

disinfection

guidelines

for

materials,

and

the

use

of

disposable

sterile

material.

Other

rare

modes

of

postoperative

contamination

may

be

mentioned,

particularly

hematogenous

ones

from

an

infection

occurring

in

postoperative

critical

care

(catheter

bacteremias

[27]

or

pneumonia)

or

by

direct

bacterial

inoculation

of

the

operative

site

when

changing

wound

dressing

in

patients

presenting

with

scarring

abnormalities.

Three

major

hypotheses

can

be

considered

concerning

the

chronology.

The

infection

is

localized

after

contamination,

responsible

second-

arily

for

localized

sternal

osteomyelitis,

inducing

the

disunion

of

fasciae.

Other

authors

believe

there

is

first

a

separation

of

sternal

margins

leading

to

the

disunion

of

fasciae

secondarily

colonized

by

bacteria.

The

last

admitted

hypothesis

is

that

of

the

poor

drainage,

with

a

large

stagnant

collection,

favoring

bacterial

development

[28].

5.

Microbiology

Staphylococci

are

the

main

bacteria

responsible

for

post-

operative

SSI,

even

if

their

proportion

may

vary

according

to

reports.

S.

aureus

accounts

for

40

to

60%

of

strains

causing

mediastinitis.

Coagulase

negative

staphylococci

are

involved

in

20

to

30%

of

cases

(Table

1).

20

to

30%

of

mediastinitis

cases

are

caused

by

Gram-negative

bacilli

and

rarely

by

yeasts

[28].

Some

authors

have

described

various

types

and

times

of

bacte-

rial

contamination

(pre-,

per-,

and

postoperative)

according

to

microbiological

documentation

[13].

Table

1

Microbiological

documentation

of

mediastinitis

after

cardiac

surgery.

Documentation

microbiologique

des

médiastinites

après

chirurgie

cardiaque.

Microbiology

of

mediastinitis

Gram

positive

Cocci

Staphylococcus

aureus

40%

Coagulase

negative

Staphylococcus

30%

Gram

negative

Bacilli

Escherichia

coli

5%

Enterobacter

spp.

10%

Klebsiella

spp.

3%

Proteus

spp.

2%

Pseudomonas

spp.

2%

Other

Candida

<

2%

Polymicrobial

10–40%

From

[29].

6.

Risk

factors

associated

with

mediastinitis

Many

authors,

over

the

last

20

last

years,

have

well

described

the

risk

factors

for

mediastinitis,

especially

in

patients

having

undergone

coronary

bypass,

which

often

overlap.

The

patients

may

be

contaminated

before,

during,

or

after

surgery,

and

any

re-

operation

exposes

to

the

risk

of

SSI.

The

risk

factors

are

related

to

the

patient

(age,

sex,

obesity,

diabetes,

respiratory

insufficiency),

to

surgery

(context

of

emergency,

type

of

surgery,

operative

time,

early

surgical

revision

for

bleeding)

and

to

hospitalization

and

its

environment

(duration

of

preoperative

stay,

patient

preparation)

[8,29,30].

The

main

risk

factors

associated

with

postoperative

SSI

are

listed

in

Table

2.

6.1.

Risk

factors

related

to

patients

Obesity

was

identified

as

an

independent

risk

factor

for

mediastinitis

by

many

authors.

The

severely

obese

patients

Table

2

Main

risk

factors

for

mediastinitis

after

cardiac

surgery.

Principaux

facteurs

de

risque

pour

une

médiastinite

après

chirurgie

cardiaque.

Main

risk

factors

of

mediastinitis

References

Related

to

patients

Age

[31]

Sex

[29,31]

Obesity

[30–32]

Diabetes

[31,33]

COBP

[15,29,31]

Nasal

Staphylococcus

aureus

carriage

[24,34]

Related

to

hospitalization

Duration

of

preoperative

hospitalization

[30]

Related

to

surgery

Surgical

time

[1,33]

Coronary

bypass [15]

Use

of

internal

mammary

arteries

[1,15,35–38]

Early

revision

for

bleeding

[15]

Other

NNIS

infectious

risk

score

≥

2

[15]

Please

cite

this

article

in

press

as:

Lepelletier

D,

et

al.

Epidemiology

and

prevention

of

surgical

site

infections

after

cardiac

surgery.

Med

Mal

Infect

(2013),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.003

ARTICLE IN PRESS

+Model

MEDMAL-3432;

No.

of

Pages

7

4

D.

Lepelletier

et

al.

/

Médecine

et

maladies

infectieuses

xxx

(2013)

xxx–xxx

[BMI

>

35

kg/m2]

had

increased

risks

for

comorbidity

because

of

a

longer

hospital

stay

than

non-obese

patients,

and

a

lower

5-

year

survival

rate

with

a

Kaplan

Meier

analysis

and

multivariate

analysis

using

Cox’s

regression

model

[32].

The

peri-operative

antibiotic

doses

administrated

to

obese

patients,

not

adapted

to

their

distribution

volume,

and

the

difficulties

to

implement

an

operative

field

could

account

for

this

risk

[39].

Diabetes,

and

especially

peri-operative

hyperglycemia,

also

increases

the

infectious

risk

after

cardiac

surgery.

More

precisely,

elevated

glycemia

(>

200

mg/dL)

on

the

first

and

second

postoperative

days

could

be

associated

to

an

increase

of

sternal

infections

in

diabetic

patients

and

peroperative

control

of

glycemia

could

decrease

the

morbidity

[33].

6.2.

Risk

factors

related

to

the

procedure

Some

surgical

techniques

may

also

be

associated

with

the

risk

of

mediastinitis.

This

is

why

using

either

of

the

two

internal

thoracic

arteries

(ITA)

in

patients

for

coronary

bypass

remains

quite

controversial

[35].

Using

the

two

ITA

results

in

a

signif-

icant

improvement

of

survival

and

of

postoperative

outcome.

Man

authors

have

reported

a

decrease

revision

surgery

rate

for

revascularization

compared

to

patients

whose

bypass

was

made

with

the

great

saphenous

vein.

These

assets

are

counterbalanced

by

the

significantly

increased

risk

of

SSI,

especially

in

obese

and

diabetic

patients

who

should

benefit

the

most

from

the

dou-

ble

internal

thoracic

vascularization

[36].

There

are

alternative

procedures

for

these

patients

including

the

strict

control

of

peri-

operative

glycemia

[37]

and

the

skeletonization

of

arterial

grafts,

minimizing

sternal

devascularization

[38].

The

other

risk

factors

related

to

surgery

are,

early

revision

surgery,

the

more

often

for

postoperative

hemorrhage,

often

mentioned

as

a

risk

factor

for

sternal

infection,

especially

when

the

initial

surgery

was

long

and

complicated

[15,40].

A

mediastinal

hematoma

may

develop,

because

of

the

bad

hemostatic

quality

of

sternal

closure,

favoring

serous

fluid

collection

and

necrotic

material

in

which

bacteria

may

proliferate

[41].

7.

Prevention

strategy

The

occurrence

of

a

postoperative

SSI

is

due

to

several

factors

and

its

prevention

relies

on

the

control

of

risk

factors

related

to

patients,

to

the

procedure,

and

to

hospital

environ-

ment,

during

the

pre,

per,

and

postoperative

periods.

The

French

Society

for

Hospital

Hygiene

(French

acronym

SFHH)

issued

recommendations

for

the

prevention

of

SSI

in

2004,

“Preop-

erative

management

of

the

infectious

risk”

in

partnership

with

all

surgery

learned

societies

[7],

“Air

management

in

the

oper-

ating

room”

[42],

and

more

recently

in

2010

“Monitor

and

prevent

care

related

infections”

in

collaboration

with

the

French

National

Authority

for

Health

(French

acronym

HAS)

[8].

The

2004

recommendations

are

currently

being

reviewed

to

take

into

account

the

evolution

of

published

scientific

data

on

nasal

S.

aureus

decolonization

to

decrease

the

rate

of

S.

aureus

SSI

and

on

the

patient’s

skin

preparation.

The

1999

CDC

recom-

mendations

[10]

in

the

USA

have

been

completed

more

recent

publications,

specifically

adapted

to

cardiac

surgery

[43],

espe-

cially

postoperatively

at

home

[44].

These

measures

are

classified

by

levels

of

recommendations

and

of

evidence

(Table

3).

They

especially

concern

the

preopera-

tive

period

and

include

the

patient’s

body

skin

preparation

(body

hair

removal,

preoperative

shower,

antisepsis

of

the

operative

site

with

an

alcohol

based

antiseptic),

preparation

and

dressing

of

the

surgical

team,

and

environment

control

of

the

operating

room

and

devices.

These

prevention

measures

were

completed

by

recommendations

on

surgical

antibioprophylaxis

issued

by

the

French

Society

of

Anesthesiology

and

Critical

Care

[6]

and

specific

cardiac

surgery

data

[45].

The

decolonization

of

nasal

S.

aureus

carriage

is

currently

the

most

debated

prevention

measure

related

to

the

patient.

Many

authors,

between

2000

and

2010,

reported

no

significant

impact

of

decolonization

on

the

rate

of

S.

aureus

SSI

because

of

differences

in

the

methodological

approach

of

decolonization

strategies

and

types

of

procedures

studied

[24,34].

The

authors

of

a

randomized,

double

blind,

placebo

controlled

study

made

in

2010,

in

the

context

of

a

multicentric

clinical

trial,

reported

the

effectiveness

of

rapid

S.

aureus

screening

on

admission

and

nasal

decolonization

with

mupirocine

only

in

patients

identi-

fied

as

S.

aureus

carriers,

associated

to

body

showering

with

chlorhexidine

gluconate

antiseptic

soap,

and

oro-pharyngeal

decolonization,

on

the

rate

of

deep

S.

aureus

infections,

essen-

tially

in

cardiac

surgery

(the

study

also

included

other

types

of

surgery

but

in

smaller

samples)

compared

to

the

placebo

con-

trol

group

including

patients

carrying

S.

aureus

(79%

decrease,

OR

0.21.

CI95% 0.07–0.62)

[46].

The

trial

results

will

soon

be

integrated

in

the

new

recommendations

of

the

French

Society

for

Hospital

Hygiene,

to

be

issued

in

2013.

Nevertheless,

the

implementation

mode

of

this

decolonization

strategy

(with

or

without:

prior

nasal

screening,

screening

method,

decoloniza-

tion

period)

must

still

be

evaluated

and

the

occurrence

of

SSI

due

to

other

microorganisms

must

be

monitored.

Using

a

sponge

impregnated

with

local

diffusion

antibiotics

on

the

operative

site

(gentamycin)

is

debated

as

a

peroperative

prevention

measure;

recent

scientific

publications

on

this

issue

are

often

contradic-

tory

[47,48].

This

measure

has

not

sufficiently

demonstrated

its

effectiveness,

even

if

some

cardiac

surgery

units

use

it

success-

fully.

The

authors

of

recent

studies

have

reported

the

contribution

of

education

programs

and

of

prevention

focusing

on

some

meas-

ures

grouped

as

“bundles”,

set

of

measures,

which

observed

and

assessed

at

the

same

time,

allow

obtaining

a

decrease

of

SSI

rates,

demonstrating

the

multimodal

aspect

of

prevention

strategies.

These

interventional

programs

include

some

meas-

ures

such

as

the

patient’s

skin

preparation,

nasal

screening

of

patients,

nasal

decolonization

with

mupirocine,

evaluation

and

switch

of

antibioprophylaxis,

especially

for

patients

carrying

methicillin

resistant

S.

aureus

(MRSA),

barrier

measures

in

the

operating

room

(gloves),

and

compression

devices

to

prevent

mechanical

postoperative

scar

disunion

(obese

patients,

patients

presenting

with

chronic

bronchitis),

[49,50].

A

prevention

pro-

gram

implemented

at

the

Nantes

hospital

center

during

more

than

10

years,

allowed

to

decrease

the

rate

of

mediastinitis

100

cardiac

surgery

procedures

from

2.1%

in

2001

to

1.1%

in

Please

cite

this

article

in

press

as:

Lepelletier

D,

et

al.

Epidemiology

and

prevention

of

surgical

site

infections

after

cardiac

surgery.

Med

Mal

Infect

(2013),

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.medmal.2013.07.003

ARTICLE IN PRESS

+Model

MEDMAL-3432;

No.

of

Pages

7

D.

Lepelletier

et

al.

/

Médecine

et

maladies

infectieuses

xxx

(2013)

xxx–xxx

5

Table

3

Prevention

of

surgical

site

infections

(level

and

proof

of

guidelines

2004

and

number

of

recommendation

2010).

Principales

mesures

de

prévention

des

infections

du

site

opératoire

(niveau

de

recommandation

et

de

preuve

2004

et

référence

de

la

recommandation

2010).

Prevention

measures

Recommendations

2004

[7]

Recommendations

2010

[8]

Preoperative

Surveillance

of

surgical

site

infections –

R91

Delayed

surgery

in

case

of

intercurrent

infection

Yes

(A2)

Nasal

Staphylococcus

aureus

decolonization

No

(E-2)a

No

shaving

or

hair

removal

Yes

(B-1)

At

least

one

preoperative

shower

with

antiseptic

soap

Yes

(A-1)aR94

Mouthwash

with

antiseptic

solution

Patient

dressed

with

no-woven

or

micro-fiber

fabric

Yes

(B-1)

Yes

(B-3)

R93

Peroperative

(intra-operating

room)

Disinfection

of

hands

with

hydro-alcoholic

gel

–

Detergence

with

antiseptic

soap

followed

by

broad

disinfection

of

the

operative

site

Yes

(A-1)aR96

Brushing

with

an

alcoholic

antiseptic

solution

Yes

(B-3)aR94

100%

cotton

patient

drapes

No

(E-3)

Adequate

surgical

garb,

operating

room

discipline

and

use

of

a

check-list

–

R97

Quality

of

air

the

operating

room

–

R98

Postoperative

Maintaining

glycemia

<

2

g/L

Yes

(A-1)

Mouthwash

with

antiseptic

solution

Yes

(B-1)

Traceability

of

the

following

Yes

(B-3)

Surgical

program

planning

R97

Antibioprophylaxis

R95

Patient’s

cutaneous

preparation

Identification

of

operators

Elements

of

the

NNIS

infectious

risk

score

Medical

material

and

devices

used

Cleaning

procedures

Chronology

of

events

aUnder

revision

2013.

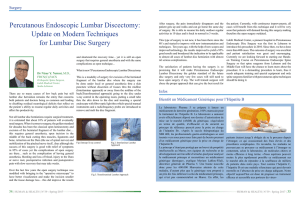

2011

(P

=

0.05)

(Fig.

1).

During

this

period,

the

number

of

pro-

cedures

in

adults

with

extra

corporeal

circulation

increased

from

1100

to

1486,

including

590

coronary

bypass

and

780

valvular

surgery

procedures.

This

prevention

program

chronologically

integrated

several

measures:

retrospective

analysis

of

SSI

and

direct

observation

of

the

patient’s

skin

preparation

(2001),

prospective

surveillance

of

SSI

(2002),

drafting

and

implemen-

tation

of

a

new

operating

mode

for

the

patient’s

skin

preparation

Fig.

1.

Incidence

of

mediastinitis/100

cardiac

surgery

procedures

and

chronology

of

key

prevention

measures

implemented

from

2001

to

2011

at

the

Nantes

university

hospital.

Évolution

du

taux

d’incidence

des

médiastinites/100

interventions

en

chirurgie

cardiaque

et

chronologie

des

principales

mesures

de

prévention

implémentées

sur

une

période

de

11

ans

(2001–2011)

au

centre

hospitalier

universitaires

de

Nantes.

6

6

7

7

1

/

7

100%