Fiscal Havens: Just a Matter of

Harmful Tax Competition?

A Literature Review

Camilla FIORINA

M2 IMPF – 2019/2020

2

Index

INDEX 2

1. INTRODUCTION 3

2. TAX HAVENS 4

2.1 Definitions and formal lists of Tax Havens 4

2.3 Determinants of Tax Havens 5

3. WHO ARE THE USERS OF TAX HAVENS? 6

3.1 Multinational companies and tax avoidance 7

3.2 Methods of avoidance and evasion by individuals 9

4. TAX HAVENS AND ECONOMIC GROWTH 10

4.1 Economic growth in tax havens 11

4.2 The impact of preferential tax regimes in developed countries 11

4.3 The impact of preferential tax regimes in developing countries 12

5. CONCLUSIONS 13

6. REFERENCES 14

6.1 Main references 14

6.2 Other empirical evidences 14

3

1. Introduction

In recent years tax havens have earned a place of honor at the center of international scandals and

controversies, so much so that they are now very familiar terms even to non-economists.

The growing integration of the financial markets and the development of new technologies that

have made capital mobility faster and more convenient have allowed the proliferation of these

financial realities.

Their huge success, and the disproportionate amount of international capital that is drawn into their

financial systems, have attracted the attention of scholars and policymakers, mainly because of the

concern that the success of tax havens occurs at the expense of non-havens, in particular through

the erosion of the tax base of the latter. Also, thanks to their policy of bank secrecy, they could

potentially be the home to many illegal activities.

The international interest in tax havens becomes a collective reaction in 1998 when the OECD

introduces for the first time what is now known as its Harmful Tax Practices initiative. The objective

was to “develop measures to counter the distorting effects of harmful tax competition on

investment and financing decisions and the consequences for national tax bases” (OECD, 1998).

The initiative criticized some of the most important features of tax havens, namely the use of

preferential tax regimes that offer very low tax rates exclusively to non-residents and the limited

availability to exchange financial information with the rest of countries. To discourage countries

from making use of policies which enhance harmful tax competition, the OECD tracked down all the

countries which were considered to be tax havens and created a “black-list” of those which didn’t

agree to commit to exchange information.

This list, which in 2000 included 35 jurisdiction, is updated every time a country agrees to cooperate

and in 2015 it only counted 3 countries: Andorra, Lichtenstein and Monaco (Gravelle, 2015).

Although this may seem to indicate a progress in the fight against tax havens, evidence do not show

a reduction in their activity. On the contrary, they continue to attract huge flows of foreign capital

undisturbed.

The aim of this literature review is to provide a general overview, yet quite comprehensive, of the

controversial reality of tax havens.

The work is structured as follows: session 2 serves as an introduction to the general concept of tax

havens. Session 3 provides some insights about how multinational corporations and wealthy

individuals make use of tax havens most of the time to, respectively, avoid and evade taxes. Findings

are supported with empirical evidence. Session 4 reports the different points of view of scholars

about the impact of tax havens on world’s economic growth. Session 5 concludes.

4

2. Tax havens

2.1 Definitions and formal lists of Tax Havens

International regimes, intended as the set of rules and governance structures established together

by nation states, have always helped to maintain and preserve the delicate balances between

countries, and to manage their conflicts.

With the arise of globalization and spread of multinational enterprises, international tax regimes

have been established, to manage the complex issue of taxation of income produced by

multinational corporations worldwide.

In this context, the Organization for the Economic Development and Cooperation (OECD) considers

tax havens as “renegade states”, intended as countries whose “tax practices are salient to the

regime but whose behavior does not comply with the regime’s descriptive norms and practices”,

thus weakening regime effectiveness (Eden & Kurdle (2005)).

In 1998, in its report “Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue”, the OECD provided some

practical guidelines for helping the governments to identify tax havens and came up with the key

factors which characterize tax havens:

1. No or only nominal taxes

2. Lack of effective exchange of information

3. Lack of transparency

4. The absence of a requirement that the activity needs to be substantial

As reported by Hines (2010) scholars generally agree on the fact that tax havens are countries and

territories that offer low tax rates and favorable regulatory policies to foreign investors.

On the other hand, the relative importance of the other features strictly depends on the context.

Some authors have tried to include them in their definition of tax havens. For example, Eden &

Kurdle (2005) claim that tax havens can be grouped according to the type of taxation and financial

services offered and according to the type of activities which are privileged.

For example, when low tax rates attract capital which induces changes in the real added value of

the tax haven, they can be categorized as production haven – for example Ireland. On the other

hand, when tax havens specifically design taxes rates to induce firms to incorporate in their

jurisdictions, regardless of the physical location of shareholders, are called headquarters haven – as

Belgium and Singapore. To conclude, sham havens – group which includes most of Caribbean and

Pacific tax havens, Switzerland, Luxembourg and Austria – serve as headquarters havens but offer

also high secrecy and specialize in allowing personal income-tax evasion.

However, boundaries of these categorizations are quite fuzzy and variable over time, especially due

to some efforts by OECD and national governments to fight bank secrecy.

Because of the lack of an agreed-upon definition of tax havens, many different lists have been

formulated by scholars and institutions over time.

5

The OCED created an initial list of tax havens in 2000 which changed much over the years. However,

the list did not include some low-tax member of the OECD, as Ireland, Switzerland and Luxembourg.

Moreover, it created a “black-list” of those which didn’t agree to commit to exchange information.

Currently, the OECD divides countries in three lists: a white list of countries implementing an agreed-

upon standard, a gray list of countries that have committed to such a standard, and a black list of

countries that have not committed. However the lists of the OECD can sometimes be biased by

some political pressure.

The Tax Justice Network proposes a very large list of tax havens, including some specific cities and

areas, as New York, the City of London, Trieste and many others. However, not everyone agrees on

this categorization.

Hines (2010) proposes a quite comprehensive list of 52 jurisdictions which can be recognized as tax

havens, based on their low business tax rates, the self-promotion as financial centers and whether

they were included in the list of other authorities sources, as other scholars, national governments

or international organization as the OECD.

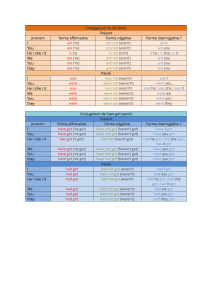

Table 1 – List of Tax Havens

2.3 Determinants of Tax Havens

By looking at the list proposed by Hines (2010), it immediately stands out that the countries and

territories included in the list are not randomly distributed but share some common characteristics.

Dharmapala and Hines (2009) empirically investigate what are the determinants of becoming or not

a tax haven.

From their work it emerges that tax havens are generally small countries (or territories) with the

population not exceeding one million. This happens because small jurisdictions can only be price-

taker when it comes to international tax competition, meaning that any of their tax burden cannot

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

1

/

14

100%