French Presidential Candidates' Websites Interactivity Analysis

Telechargé par

Houda Bachisse

http://ejc.sagepub.com/

Communication

European Journal of

http://ejc.sagepub.com/content/25/1/25

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/0267323109354231

2010 25: 25European Journal of Communication

Darren G. Lilleker and Casilda Malagón

Levels of Interactivity in the 2007 French Presidential Candidates' Websites

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

can be found at:European Journal of CommunicationAdditional services and information for

http://ejc.sagepub.com/cgi/alertsEmail Alerts:

http://ejc.sagepub.com/subscriptionsSubscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.navReprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.navPermissions:

http://ejc.sagepub.com/content/25/1/25.refs.htmlCitations:

at Universite du Quebec a Montreal - UQAM on September 15, 2011ejc.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Levels of Interactivity in the

2007 French Presidential

Candidates’ Websites

Darren G. Lilleker and Casilda Malagón

Bournemouth University, UK

Abstract

Amid many discussions of disengagement between the public and political sphere, the Internet is offered

as a potential solution capable of bridging the gap between elected and elector. E-communication tools

have been increasingly prominent during recent election campaigns, and much attention was given to

the 2007 French presidential candidates’ use of the Internet. It was suggested they had moved beyond

simply providing information and were opening up a dialogue with the electorate. This interactivity

has the capacity to reduce disengagement and revitalize democracy. However, in defining interactivity,

the trend online is to think of participatory open dialogue as opposed to closed sender–receiver

feedback loops. In order to assess the role interactivity played within this contest, and to gain some

sense of the future use of interactive tools, this study tested a sample of pages from the websites

of Nicolas Sarkozy and Ségolène Royal, the two main challengers in the contest, against a six-part

interactivity model, and analysed the discourse and language in terms of its encouraging interaction.

While some shifts in behaviour were found, the campaign retained the caution that is normal for

electoral candidates, which reduced the extent to which participatory interactivity took place.

Keywords

elections, interactivity, Internet, political campaigning, Web 2.0

In 2001, Manuel Castells opened his book The Internet Galaxy with simple news: ‘the

internet is the fabric of our life’ (Castells, 2001: 1); this comment hints at two important

issues raised in this article. First, it is argued that the Internet has a potentially revolution-

ary impact upon society and its communication. Second, the Internet has the capacity to

also reshape political communication and campaigning. However, while the citizens

explore the virtual world of the Internet as nomads shaping the contours as they surf;

political communication remains fixed within boundaries and parameters prescribed by

Article

Corresponding author:

Darren G. Lilleker, The Media School, Bournemouth University, Fern Barrow, Poole BH12 5BB, UK.

Email: [email protected]

European Journal of Communication

25(1) 25–42

© The Author(s) 2010

Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermission.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0267323109354231

http://ejc.sagepub.com

at Universite du Quebec a Montreal - UQAM on September 15, 2011ejc.sagepub.comDownloaded from

26 European Journal of Communication 25(1)

electoral goals. Perhaps because of the differing goals of elected and electors, studies of

the Internet offer highly mixed predictions (Bimber and Davis, 2003; Margolis and

Resnick, 2000); and often these prove unfounded. However, incrementally we find the

Internet playing an increasingly important role within political campaigning and possi-

bly demonstrating a shift towards a more interactive, multidirectional form of communi-

cation taking place within both candidate and media websites during elections in order to

try and adapt to social developments in Internet use.

The majority of studies focus on Anglo-American campaigners’ use of Internet tools

during election campaigns, with less focus being given to other democracies. While

French politics has not seen new media strategists become an integral part of campaign

planning and execution, as in the US in 2004 (Howard, 2006), French parties were quick

to build websites in time for the 1997 general election and it became a necessary elec-

toral tool. While Villalba’s study of the use of the Internet before and during the 2001

presidential election found that the majority of parties offered a range of information to

visitors to websites, true interaction was limited and most communication was unidirec-

tional (Villalba, 2003). This is fairly common of Internet use by political parties, and is a

trend mirrored across most of northern Europe (Jankowski et al., 2005).

However, facilitated by the use of video sharing sites like YouTube and social networking

tools to communicate with voters, it is suggested that we have reached a turning point in

political communication (Castells, 2007: 255). The French presidential campaign of 2007

seemed to offer evidence to support Castells’ claim. While public interest and participation

remained high throughout the contest, the aspect that seemed to set this campaign apart was

the use of ICT (XiTi Monitor, 2007a, 2007b). French, UK and US media commented on the

use of blogs, embedded videos and Second Life, suggesting a different style of campaigning

was emerging. While there was some retreat as both candidates found themselves the victims

of user-generated content posted to YouTube (King, 2007), their use of ICT was still vaunted

as encouraging participation of a previously unseen level and extent (XiTi Monitor, 2007b).

While it remains impossible to accurately predict what ICT use by candidates or the public

can do for democracy, as evidence thus far seems equivocal, using France as a case study we

wish to provide some assessment of the role of ICT in campaigns and assess how the use of

technologies in a political context can encourage participation, discourse and interaction, so

strengthening what Dahlgren refers to as ‘the character of democracy’ (Dahlgren, 2005: 147).

What we assert is that, because the success of political parties and political candidates

is so linked to their reputation (Haywood, 2005), they are both the main benefactors and

most at risk from new technology; hence they attempt to harness the Internet communi-

cation tools, while also showing caution regarding the extent to which visitors can upload

content and join in open dialogue (Stromer-Galley, 2000). This latter form of interaction

has traditionally been lacking from political web use. However, as the presidential can-

didates competed over use of tools that allowed them to reach out to the voters in a way

previously unseen (see Benhold; 2007; Scott, 2006), interest increased. The blogosphere

began asking if this was an effort to enhance democratic life or just another campaign

gimmick; were both candidates striving to interact with their voters and was interaction

possible, appropriate and actually desirable (Uther, 2007)?

At a more theoretical level, however, we can suggest that interaction among voters,

and between voters and political candidates and elected representatives, is crucial for

at Universite du Quebec a Montreal - UQAM on September 15, 2011ejc.sagepub.comDownloaded from

Lilleker and Malagón 27

reinvigorating democracy. France shares similar trends of political disengagement with

much of Western Europe, although there is unsurprisingly the highest level of participa-

tion in lawful public demonstrations (European Social Survey, 2002). A frequently

offered solution to disengagement and political apathy is civic engagement within a dis-

cursive arena: a political public sphere. While we have moved a long way from a society

where the bourgeoisie discuss public affairs in salons, the Internet is argued to facilitate

participation in political debate. Though Papacharissi (2002: 16) is ambiguous regarding

the potential of a virtual, electronic-based, public sphere, he makes a key point that ‘The

widening gaps between politicians, journalists, and the public will not be bridged, unless

both parties want them to be.’ We argue here that a significant factor in bridging the gap,

and building a political public sphere, would be for political candidates, parties and

elected representatives to show a willingness to engage the public in open debate. This

entails engaging in a conversation, one that new technologies facilitate but has been a

hitherto underused feature within political communication.

Employing a model for measuring the extent to which interactivity is encouraged and

allowed, this study examines how the two main French presidential candidates, Ségolène

Royal and Nicolas Sarkozy, approached the opportunities that new media technology

had to offer in France in 2007. While a single case study only, given the lesson-learning

between nations and election, our findings could give strong indications of the direction

that political use of the web may take.

Conceptualizing interactivity

While it can be argued that the inclusion of an email address offers the potential for dialogue,

there must also be reasons for clicking on the address to send a message; thus interactivity is

a function of both the inclusion of interactive tools as well as of the language used when

offering that tool. While there is academic consensus on the importance of studying the levels

of interactivity in political websites, there is less consensus surrounding what interactivity is

and how it can be recognized (Bucy, 2004; Sundar, 2004). Interactivity often appears to be a

perceptual concept, contested, underdefined and undertheorized (Bucy, 2004; Kiousis, 2002;

McMillan and Hwang, 2002). The classic definition suggests that for a message to be interac-

tive it has to be transformed by the exchange of communication: in other words, a conversa-

tion. Kiousis (2002) offers a more complete definition of interactivity as: ‘the degree to

which a communication technology can create a mediated environment in which participants

can communicate (one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many), both symmetrically and

asymmetrically, and participate in reciprocal message exchanges (third-order dependency).

With regard to human users, it additionally refers to their ability to perceive the experience

as a simulation of interpersonal communication and increase their awareness of telepresence’

(Kiousis, 2002: 372). For Kiousis, interactivity refers to any communication technology,

considers time without excluding asymmetrical communication (like email) and stresses the

value of content modification by the user and the author. Therefore, interactivity is not simply

a function of technology, or the ability to interact with a website through hyperlinks or wid-

gets, but a dialogic process between users of a website including the creator.

Jennifer McMillan (2002a) captured the essence of the Kiousis definition in her model

combining an information traffic model with Grunig and Dozier’s (1992) model of

at Universite du Quebec a Montreal - UQAM on September 15, 2011ejc.sagepub.comDownloaded from

28 European Journal of Communication 25(1)

public relations practice to develop the four-part model of interactivity. The model

depends on two variables: direction of communication and the level of receiver control.

In this model, interactivity is not a binary concept, it is a progressive continuum. At the

highest end of it, what McMillan calls mutual discourse, we find that the roles of the

sender and the receiver are interchangeable.

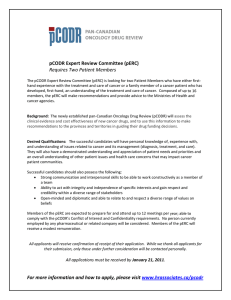

This model, combined with the McMillan’s typology of interactivity, as summarized in

Table 1, proves useful to measure the presence of interactive technical features of websites.

However, when used as an analytical tool, there are drawbacks. First, the continuum is

rather simplistic (high or low control). To reduce this limitation, and offer a more sensitive

tool of measurement, Ferber et al. (2007) enriched the model by adding three-way com-

munication (Figure 1), this now encompasses communication where any number of par-

ticipants can interact via comments boards or chat-rooms. When linked to content and

discourse analysis of language, risks of limitations and subjectivity are reduced (Liu, 2003).

Language and the internet: enabling interactivity

The dynamic nature of language in the Internet with its ever-increasing set of variations

(Crystal, 2006) has prompted many studies. However, the link between language and

interactivity has not been fully explored in the context of political websites. The domina-

tion of the field of study by feature-based analysis means there is a lack of language- or

subject-based studies that analyse a ‘range of communication forms’ (Mayer, 1998).

Rhetorical and discourse attributes can affect perceived interactivity and desired user

engagement (Wood and Kroger, 2000).

Thus the power of language should be emphasized. Fairclough (2001, 2003) and van

Dijk (2001) have made clear links between language used and the construction of reality.

While identity is not made up solely of discourse, it is the public embodiment of identity

that constitutes website text. Therefore, following Fairclough’s definitions, discourse

refers to language used in a particular way to communicate specific values, and ulti-

mately refers to ‘a social construction of reality’ (Fairclough, 1995: 18). Thus, the

One-way Two-way Three-way

Feedback Mutual discourse Public discourse

S R PP

Level of

receiver

control

High

Low

PPP

Monologue Responsive dialogue Controlled response

S RS RS R

P

Figure 1. Ferber et al.’s six-part model of cyber-interactivity

Source: Ferber et al. (2007).

at Universite du Quebec a Montreal - UQAM on September 15, 2011ejc.sagepub.comDownloaded from

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

1

/

19

100%