!"#$%&'(%)(*+,&"-./(0"$,&.$1&,

2"/3"/4('%1&(5.'

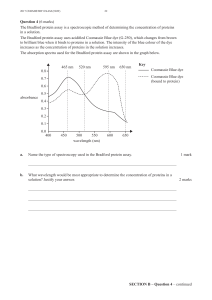

!"#$%&'()#*+)')#,(#-%#(&$+#*+,-.#/(#the#+,(*%'0#%"#12)',$/-#3,*)'/*&')4#1*#5)(*#*+,(#$%&'()#

6,33#5)#a#+,(*%'04#7%*+,-.#$/-#')83/$)#*+)#)98)',)-$)#%"#')/:,-.#5&*#2%(*#8)%83);#)<)-#,-#

/# 3,")=2)# %"# ')/:,-.;# /')# &-/53)# *%# ')/:# all# 12)',$/-# 3,*)'/*&')# /-:# 2%(*# %"# &(# >-:# ,*#

+)38"&3#*%#3)/'-#"'%2#*+)#)98)',)-$)#%"#%*+)'(4#?,@)#/33#(&'<)0#$%&'()(;#*+,(#$%&'()#6,33#5)#

8/'=/3# ,-# 5%*+# ()-()(# %"# *+)# *)'2A# *+)')# 6,33# 5)# ./8(# B3)C# "%'# 0%&# *%# >33D# /-:# ,*# 6,33#

8'%5/530# ')<)/3# 20# %6-# */(*)(4# E+)# $%&'()# ,(# :)(,.-):# *%# +)38# 0%&# *+,-@# /5%&*# /-:#

(,*&/*)# ,-# 5%*+# =2)# /-:# (8/$)# *+)# 12)',$/-# /&*+%'(# 0%&# ')/:4# F*# ,(# 2)/-*;# ,-# %*+)'#

6%':(;#*%#+)38#0%&#>-:#0%&'#6/04

Required(Reading

G*&:)-*(#6,33#5)#)98)$*):#*%#')/:#*+)#8/((/.)(#8%(*):#)/$+#6))@4#

Student(assessmentA

E+)')# 6,33# 5)# /# %-)H+%&'# )-:H%"H*)'2# )9/2,-/=%-# ,-# 6+,$+# (*&:)-*(# 6,33# 5)# .,<)-# /#

8/((/.)# 50# /-# 12)',$/-# /&*+%'4# I%&# 6,33# 5)# )98)$*):# *%# :,($&((# *+)# 8/((/.);#

:)2%-(*'/=-.#0%&'#@-%63):.)#%"#JD#*+)#6/0#,*#$/-#5)#())-#/(#$%--)$*):#*%#*+)#6%'@#%"#

%*+)'#12)',$/-#/&*+%'(#/-:#KD#*+)#6/0(#,-#6+,$+#,*#,(#%',.,-/3L:,M)')-*#"'%2#*+)#6%'@#

%"#%*+)'#/&*+%'(4#I%,33#5)#)98)$*):#*%#:%#*+,(#,-#KNN#*%#ONN#6%':(4

67.$(8%(6,(9,./(:'(;*+,&"-./(<"$,&.$1&,=>

E+)#/-(6)'#,(#-%*#/(#%5<,%&(#/(#,*#2/0#())24#F(#P12)',$/-#3,*)'/*&')Q#3,*)'/*&')#6',R)-#

%-# *+)# 12)',$/-# $%-=-)-*S# F-# 6+/*# ,(# -%6# *+)# T-,*):# G*/*)(S# F-# %*+)'# 6%':(# ,(# ,*#

(%2)+%6# $%--)$*):# 6,*+# 83/$)S# E+)# U&)(=%-# ,(# /33# *+)# 2%')# $%283,$/*):# (,-$)# *+)#

5%':)'(#%"#*+/*#83/$);#*+)#T-,*):#G*/*)(;#+/<)#5))-#'):)>-):#2%')#*+/-#%-$)#(,-$)#*+)0#

>'(*#$/2)#,-*%#)9,(*)-$)A#*+)#T-,*):#G*/*)(#/(#0%&#@-%6#+/<)#-%*#/36/0(#5))-#6+/*#*+)0#

/')#*%:/04#V&'*+)'2%');#P12)',$/Q#6/(#/#83/$)#,-#*+)#,2/.,-/=%-#3%-.#5)"%')#*+)#T-,*):#

G*/*)(# 6)')# )<)-# *+%&.+*# %"4# F-# "/$*;# )<)-# 5)"%')# 12)',$/# 6/(# :,($%<)'):4# 1-:# (,-$)#

3,*)'/*&')#+/(#)<)'0*+,-.#*%#:%#6,*+#*+)#,2/.,-/=%-;#6)#6,33#5).,-#6,*+#W,33,/2#X'/:"%':#

/-:# *'0# *%# *+,-@# /5%&*# *+)# $%--)$=%-# 5)*6))-# 83/$)L*+)# 7%'*+# 12)',$/-# $%-=-)-*#

*+/*#,(L/-:#*+)#,2/.,-/=%-;#*+)#6/0#/#8/'=$&3/'#83/$);#"%'#/33#(%'*(#%"#:,M)')-*#')/(%-(;#

>'):#*+)#,2/.,-/=%-#/-:#2/'@):#*+)#3,*)'/*&')#%"#*+%()# 6+%# 3,<):#*+)')4#F#6,33#-%*# 5)#

*/3@,-.# /5%&*# *+)# %'/3# *'/:,=%-# *+/*# )9,(*):# ,-# 7%'*+# 12)',$/# 5)"%')# *+)# /'',</3# %"#

Y&'%8)/-(;#/3*+%&.+#,*#,(#/-#,-*)')(=-.#(&5Z)$*#,-#,*()3"4#E+)#8)%83)#*+/*#/')#-%6#3&28):#

*%.)*+)'#&-:)'# *+)# 3/5)3#P-/=<)#12)',$/-(Q#+/:# /#')2/'@/53)# *'/:,=%-#%"#(*%'0*)33,-.#

/-:# 8)'"%'2/-$)L,-# 6+,$+# 2)2%'0# /-:# 2%:&3/=%-# %"# *+)# <%,$)# 83/0):# 2/Z%'# '%3)(4#

E+/*#*'/:,=%-#6/(#')$%.-,[):#/-:#/:2,'):#50#2/-0#%"#*+)#)/'30#()R3)'(#/-:#*'/<)33)'(4#

F-#*+,(#$%&'();#F#6,33#$%-$)-*'/*)#%-#6',R)-#3,*)'/*&')#/-:#%-#3,*)'/*&')#6',R)-#,-#Y-.3,(+4#

F-# %*+)'# 6%':(# F# 6,33# )9$3&:)# 3,*)'/*&')# 6',R)-# ,-;# (/0;# V')-$+# %'# G8/-,(+;# 6+,$+# /3(%#

)9,(*):#,-#6+/*#,(#-%6#*+)#T-,*):#G*/*)(4

6"<<".+(?&.3)%&3

@A(6"<<".+(?&.3)%&3B#(Of(Plimouth(Planta6on

E+)# \302%&*+# $%3%-0# 6/(# -%*# *+)# >'(*# Y&'%8)/-# $%3%-0# ,-# 7%'*+# 12)',$/# /-:# W,33,/2#

X'/:"%':](# /$$%&-*# 6/(# -%*# *+)# >'(*# *%# 5)# 6',R)-# %'# 8&53,(+):4# X&*# ,*# +%3:(# /# (8)$,/3#

83/$)#,-#*+)#12)',$/-#$/-%-#B,4)4;#*+)#/$$)8*):#.'%&8#%"#6%'@(#*+/*#2/@)#&8#12)',$/-#

3,*)'/*&');# Z&(*# /(# *+)')# ,(# /-# /&*+%',*/=<)# 3,(*# %"# 5%%@(# /$$)8*):# /(# ^%30# G$',8*&')D#

5)$/&()# %"# *+)# -/*&')# %"# X'/:"%':](# )98)',)-$);# 6+,$+# +/(# *+)# /R',5&*)(# %"# /-# +)'%,$#

)-*)'8',();# 5&*# /3(%# 5)$/&()# %"# *+)# (6)/*-)((# %"# X'/:"%':](# *%-);# +,(# +&2,3,*0# /-:# +,(#

$%&'/.)4#

W,33,/2#X'/:"%':#6/(#5%'-#/-:#5/8=[):#,-#I%'@(+,');#Y-.3/-:#,-#J_`N4#^)#6/(#%'8+/-):#

/*# /-# )/'30# /.)# /-:;# 6+)-# +)# 6/(# *6)3<)# B,-# JaNKD;# +)# 5)./-# *%# /R)-:# \&',*/-# B%'#

G)8/'/=(*D# 2))=-.(4# W+0# 6)')# *+)0# $/33):# \&',*/-(# /-:# G)8/'/=(*(# /-:# 3/*)'#

b,(()-*)'(S# X)$/&()# *+)0# %88%():# *+)# c+&'$+# %"# Y-.3/-:L*+)# 1-.3,$/-# c+&'$+L/-:#

(%&.+*#*%#8&',"0#,*;#*%#',:#,*#%"#6+/*#*+)0#$%-(,:)'):#)9$)(()(#%"#$)')2%-,/3#6%'(+,8#*+/*#

*+)0# (/6# /(# ,:%3/*'04# E+)0# %88%():# *+)# 8',)(*+%%:# /-:# ,-(,(*):# %-# 8)'(%-/3#

,-*)'8')*/=%-# %"# *+)# X,53)L%'# G$',8*&')4# E+)0# 6)')# $%-(*/-*30# +%&-:):# 50# 3%$/3#

2/.,(*'/*)(#/-:#,-#JaNd;#2/-0#5)./-#*%#3)/<)#Y-.3/-:#/-:#()R3)#,-#^%33/-:#6+)')#*+)0#

6)')# *%3)'/*):4# E+)0# 6/-*):# *%# ()8/'/*);# ,-# %*+)'# 6%':(;# "'%2# *+)# 1-.3,$/-# c+&'$+4#

W,33,/2#X'/:"%':#6/(#/2%-.#*+)#G)8/'/=(*(#,-#^%33/-:#6+)')#+)#2/'',):#,-#JaJe4#G)<)-#

0)/'(# 3/*)';# *+)# 6+%3)# $%-.')./=%-;# %'# 2%(*# %"# ,*;# +,'):# /# (+,8;# *+)# Mayflower,# /-:#

:)$,:):#*%#.%#/-:#()R3)#,-#12)',$/;#(*03,-.#*+)2()3<)(#P8,3.',2(4Q#X'/:"%':#/-:#+,(#6,")#

3)C# *+),'# "%&'H0)/'H%3:# (%-# 5)+,-:# /-:# X'/:"%':(# 6,");b%'%*+0# f/0;# :,):;# Z&(*# 5)"%')#

*+),'#/'',</3;#"/33,-.#%<)'5%/':L(%2)#(/0#(+)#$%22,R):#(&,$,:)4#

E+)#-)9*#0)/';#,-#JaKJ;#/C)'#*+)#:)/*+#%"#*+)#>'(*#.%<)'-%'#%"#\302%&*+;#X'/:"%':#6/(#

)3)$*):#.%<)'-%';#/#8%(,=%-#*%#6+,$+#+)#6/(#')H)3)$*):#)<)'0#0)/'#B)9$)8*#><)D#"%'#*+)#

')(*# %"# +,(# 3,");# &-=3# Ja_g;# *+/*# ,(4# Mourt's0 Rela2on;# 2)-=%-):# ,-# *+)# -%*)(;# 5/():# %-#

6',=-.(#50#W,33,/2#X'/:"%':#/2%-.#%*+)'(;#6/(#8&53,(+):#JaKK#,-#?%-:%-4#X&*#X'/:"%':#

%-30#5)./-#*%#6',*)#Of0Plymouth0Planta2on#B"'%2#6+,$+#*%:/0](#8/((/.)#,(#*/@)-D#%-30#,-#

JaeN;# *+/*# ,(;# *)-# 0)/'(# /C)'# +,(# /'',</3# ,-# *+)# 7)6# W%'3:4# X'/:"%':# 6%'@):# %-# Of0

Plimouth0Planta2on#"%'#*6)-*0#0)/'(4#/-:#,*#6/(#8&53,(+):#,-#Y-.3/-:#,-#Ja_N4

I%&# (+%&3:# ')2)25)'# *+/*# 6+,3)# W,33,/2# X'/:"%':# 6/(# /R)-,-.# \&',*/-# ()'<,$)(# "'%2#

JaNK# %-6/':(;# /-:# 3/*)'# 6+,3)# +)# 6/(# *'/<)33,-.# /$'%((# *+)# 1*3/-=$# /-:# ()R3,-.# ,-# *+)#

7)6#W%'3:;#G+/@)(8)/')](#83/0(#6)')#5),-.#8)'"%'2):#/*#*+)#h3%5)#E+)/*')#,-#?%-:%-4#

i/2)(# F# B6+%# (&$$)):):# Y3,[/5)*+# J# ,-# JaNe# /-:# 6+%# 6/(# +,2()3"# 5%*+# /# 6',*)'# /-:#

($+%3/'D#6/(#j,-.#/-:#*+)#+)/:#%"#*+)#1-.3,$/-#c+&'$+4#k)2)25)'#*%%#*+/*#*+,(#6/(#*+)#

=2)# %"# i%+-# b%--)# BJ_gKHJaeJD;# %"# X)-# i%-(%-# BJ_gKHJaeKD# /-:# %"# i%+-# f,3*%-#

BJaNdHJagOD# /-:# %"# *+)# j,-.# i/2)(# *'/-(3/=%-# B%'# 1&*+%',[):# l)'(,%-D# %"# *+)# X,53)#

BJaNOHJaJJD;#/#2/Z%'#3,*)'/'0# /-:# ($+%3/'30#&-:)'*/@,-.#$/'',):#%&*#&-:)'#*+)#/&(8,$)(#

%"#*+)#j,-.#+,2()3"4#133#*+,(#*%#.,<)#0%&#/-#,:)/#%"#*+)#3,*)'/'0#$%-*)9*#,-#6+,$+#W,33,/2#

X'/:"%':#3,<):#)<)-#/C)'#+)#3)C#Y-.3/-:4

CA(D%3B#(E7%#,/(F,%G<,H(I,/$(%/(.(8"J"/,(K&&./3("/$%($7,(6"<3,&/,##(

W,33,/2# X'/:"%':](# /$$%&-*# ')<)/3(# +,(# :)*)'2,-/=%-# *%# 2/@)# /# ')$%':# %"# *+)# 8,3.',2#

8'%Z)$*4# E+,(# 2/0# ())2# ()3"H)<,:)-*# 5&*# *+)# (*%'0# %"# *+)# \&',*/-(m# :)8/'*&');# <%0/.);#

/'',</3;# ()R3)2)-*;# /-:# *+)# :)<)3%82)-*# %"# *+)# 83/-*/=%-;# /(# 6)33# /(# *+),'# 3/(=-.#

:):,$/=%-#*%#6+/*#*+)0#(/6#/(#h%:](#8&'8%()# ,-#+,(*%'0#6%&3:#:)>-)#/#(+/8)# "%'#*+)#

6',=-.# %"# 12)',$/4# k,.+*# "'%2# *+)# <)'0# 5).,--,-.;# X'/:"%':](# /$$%&-*# $%-*/,-):# /#

U&)(=%-A#$%&3:#3/-.&/.)#)98')((#*+)#)9*'/%':,-/'0#)98)',)-$)#%"#*+)#8,3.',2(S#12)',$/#

5)$/2)# /# (%'*# %"# *)(=-.# 83/$)# "%'# 3/-.&/.)4# E+)# \,3.',2](# $%-(*/-*# ()/'$+# "%'#

8'%<,:)-=/3# 2)/-,-.(#/-:# +,::)-#')<)3/=%-(#6/(#8/'*#%"# *+)#/R)28*#*%#:,($%<)'# /-:#

&-:)'(*/-:#*+)#2)/-,-.#%"#*+)#7)6#W%'3:4#X'/:"%':#6'%*)#*+/*#+)#6/(#:)*)'2,-):#*%#

')-:)'# +,(# /$$%&-*# P,-# 83/,-)# (*03)# 6,*+# (,-.&3/'# ')./':# &-*%# *+)# (,283)# *'&*+# ,-# /33#

*+,-.(4Q#V%'#+,2;#*+)#<%0/.)#*%#7)6#Y-.3/-:#6/(#/-#/$*#%"#"/,*+;#:)',<):#"'%2#+,(#')/:,-.#

%"#8'%<,:)-=/3#(,.-(#,-#)<)'0:/0#)<)-*(4#W+/*#+)#$/33):#Q*+)#(,283)#*'&*+Q#6/(#-%*+,-.#

3)((# *+/-# *+)# /$=%-(# %"# h%:](# c+%()-# \)%83);# ()-*# %-# /# :,<,-)# )''/-:# ,-*%# *+)#

6,3:)'-)((4#^,(*%'0#,-#*+)#7)6#W%':#$%&3:;#/$$%':,-.#*%#*+,(#<,)6;#'):))2#%'#')8/,'#*+)#

(,-(#%"#*+)#!3:#W%'3:4#^,(#.%/3;#*+)#.%/3#%"#*+)#\,3.',2(#6/(#*+)#c+',(=/-#2,33)-,&2#B*+)#

*+%&(/-:#0)/'(#2)-=%-):#,-#*+)#X,53)#BRevela2on#KND#:&',-.#6+,$+#+%3,-)((#,(#2)/-*#*%#

8')</,3# /-:# c+',(*# ,(# *%# '),.-# %-# )/'*+D4# V%'# *+)# \&',*/-(;# /33# )<)-*(;# )<)-# ())2,-.30#

&-,28%'*/-*#)<)-*(;##6)')#(,.-(4

X'/:"%':](# /$$%&-*# :,:# -%*# /88)/'# %&*# %"# -%6+)')4# X)+,-:# ,*# 3/0# *+)# 8%6)'"&3# 5,53,$/3#

(*%'0#%"#*+)#\'%2,():#?/-:4#E+,(#,(#)<,:)-*;#"%'#)9/283);#,-#X'/:"%':m(#/33&(,%-#*%#\,(./+;#

6+,$+# ,(# *+)# +,33# "'%2# 6+,$+# f%()(# $%-*)283/*):# c/-//-;# *+)# 8'%2,():# 3/-:# B)4.4;#

Deuteronomy# e4KeHK_D4# V%'# X'/:"%':;# *+)# \,3.',2(# 6)')# -)6# F('/)3,*)(4# E+)0# 6)')#

')8)/=-.# *+)# X,53,$/3# (*%'0# %"# *+)# Y9%:&(# /-:# /'',</3# ,-# *+)# \'%2,():# ?/-:4# ^)# 83/$)(#

*+),'#/:<)-*&')#%-#*+)#(*/.)#%"#6%'3:#+,(*%'04#F*#,(#8/'*#%"#/#:'/2/#*+/*#.%)(#5/$@#*%#*+)#

5).,--,-.# %"# =2)4# E+),'# %5Z)$*# 6/(# *%# )25%:0# *+)# :,<,-)# 6,33# 50# 5&,3:,-.# <,33/.)(# /-:#

,28'%<,-.#*+),'#%6-#5)+/<,%&'A#*+)0#,-*)-:):#*%#5)#)9/283)(#"%'#/33#2/-@,-:4#X'/:"%':#

(/6#*+)#/'',</3#%"#*+)#\,3.',2(#,-#*+)#7)6#W%'3:#/(#8/'*#%"#/-#+,(*%',$/3#$%-=-&&2#*+/*#

5)./-#6,*+#c')/=%-#/-:#6+,$+#6%&3:#$%2)#*%#/-#)-:#6,*+#*+)#/8%$/308()4#G%#5)0%-:#

*+)# facts# ')3/*):# ,-# X'/:"%':](# /$$%&-*# *+)')# /')# $3)/'30# /33).%',$/3# /-:# *'/-($)-:)-*/3#

2)/-,-.(4#^)#())(#"/$*(#/(#-%*+,-.#3)((#*+/-#)<,:)-$)#%"#h%:](#8/'=$,8/=%-#,-#+&2/-#

+,(*%'04#

X'/:"%':](#/$$%&-*#*/@)(#*+)#(+/8)#%"#6+/*#+/(#5))-#$/33):#/#PZ)')2,/:;Q#/#8',2/'0#*08)#

%"#\&'=/-#6',=-.4#1#PZ)')2,/:;Q#B"'%2#*+)# 5%%@# %"# i)')2,/+#,-#*+)#X,53)D#,(#-%*#%-30#/#

*/3)#%"#(/:-)((# %'#6%);#5&*# /-#interpreta2ve0 /$$%&-*#%"#+/':(+,8(#/(#6)33# /(#/# $/33# "%'#

')*&'-# *%# *+)# 8&',*0# %"# )/'3,)'# =2)(4# 133# )<)-*(;# -%# 2/R)'# +%6# %':,-/'0;# ')U&,')#

($'&8&3%&(# /R)-=%-# 5)$/&()# *+)0# /')# 8/'*# %"# *+)# /33).%'/,$/3# 20(*)'04# X'/:"%':m(# Of0

Plymouth0 Planta2on# ,(# /# (%'*# %"# 2,33)-/',/-# )8,$L/-# )8,$# 6,*+%&*# /# @-%6-# %&*$%2)4#

E+,(# &-$)'*/,-*0L&-$)'*/,-*0# /5%&*# +%6# *+)# (*%'0# 6,33# )-:L)983/,-(# X'/:"%':](# -)):#

"%'#P83/,-)#(*03)4Q#P\3/,-)#(*03);Q#*+)#/$$&'/*)#')8')()-*/=%-#%"#%5()'<):#3,");#())2):#*%#

*+)#\&',*/-(#*%#5)#/#6/0#*%#')2/,-#/(#$3%()#/(#8%((,53)#*%#*+)#)(()-$)#%"#*+)#"/$*(#*%#5)#

,-*)'8')*):4

X'/:"%':](#/$$%&-*#$%-(*/-*30#*)(=>)(#*%#*+)#(+%'*$%2,-.(#%"#*+)#8,3.',2(4#F*#')8)/*):30#

3/2)-*(# *+)# ./8# 5)*6))-# :,<,-)# ,-*)-=%-(# /-:# +&2/-# "&3>32)-*4# I)*# *+)# 8,3.',2(#

8)'(,(*):# ,-# .,<,-.# *+)2()3<)(# /# $)-*'/3# '%3)# ,-# *+)# :'/2/# *+/*# h%:# +/:# :)(,.-):# "%'#

*+)2#%-#*+)#12)',$/-#(*/.);#6+,$+#*+)0#*+%&.+*#%"#/(#*+)#>-/3#(*/.)#%"#+&2/-#+,(*%'04#

h)%'.)# G/-*/0/-/;# *+)# 12)',$/-# 8+,3%(%8+)';# (/,:# *+/*# *+)# )(()-=/3# 3)./$0# %"# *+)#

\&',*/-# ,2/.,-/=%-# 6/(# 8')$,()30# *+/*# $%-n,$*# 5)*6))-# *+)# ,:)/3# /-:# *+)# ')/3;# *+)#

T*%8,/-#/-:#*+)#/$*&/3;#*+)#,-*)-=%-/3#/-:#*+)#/$$,:)-*/3;#*+)#20*+,$#/-:#*+)#)<)'0:/04#

E+)#\&',*/-(#6)')#/R)28=-.#*%#"%&-:#/#-)6#%':)'#%"#(%$,)*0#5/():#%-#/#-)6#$%<)-/-*#

/2%-.#2)-#B/#5,-:,-.#/.'))2)-*;#%'#$%28/$*D#/-:#/#-)6#')3/=%-#%"#')3,.,%-#/-:#3/64

c%R%-#f/*+)'#/-:#*+)#F-*)-(,*0#%"#\&',*/-#W',=-.

@A(E%L%/(9.$7,&(M@NNOP@QCRS(

c%R%-# f/*+)'o(# Magnalia0 Chris20 Americana# BJgNKD# 2/'@):# *+)# $&32,-/=%-# %"# *+)#

8'%$)((# %"# *08%3%.,$/3# ,-*)'8')*/=%-# B,4)4;# ,-*)'8')*/=%-# %"# (025%3(;# )(8)$,/330# ,-# *+)#

X,53)DA# *+)# "/$*(# %"# 12)',$/-# +,(*%'0# 5)$/2)# %-)# 3%-.# ')$%':# %"# *',/3(# /-:# 8'%%"(# %"#

h%:](#8'%<,:)-$)#B,4)4;#.&,:/-$)#%'#$/')D4#V%'#*+)#\&',*/-(#$+/'.):#6,*+#h%:](#)''/-:#,-#

*+)#6,3:)'-)((;#,*#())2):#*+/*#*+)#6+%3)#6%'3:#6/*$+):#/(#h%:#/-:#G/*/-#(*'&..3):#%-#

*+)#12)',$/-#(+%')4#E+),'#*/(@#6/(#*%#:,(83/$)#*+)#$)-*')#%"#+,(*%'0#"'%2#Y&'%8)#*%#*+,(#

-/''/6#(*',8#%"#3/-:4#E+)0#(/6#*+)2()3<)(#/(#/#=-0#5/-:#%"#(8,',*&/3#8,%-))'(#6+%#+/:#

/$$)8*):#h%:](#,-Z&-$=%-#*%#)(*/53,(+#+,(#j,-.:%2#,-#*+)#6,3:)'-)((4

c%R%-# f/*+)'# B-%=$)# +,(# )9*'/%':,-/'0# -/2)D# 6/(# *+)# *+,':# ,-# 3,-)# %"# *+)# f/*+)'#

:0-/(*0#B/C)'#k,$+/':#/-:#F-$')/()D4#^)#")3*#:)(=-):#"%'#3)/:)'(+,8#%"#5%*+#$+&'$+#/-:#

(*/*)4#^)#6/(#/#2/-#%"#.')/*#3)/'-,-.#/-:#%6-):#/#3,5'/'0#%"#*+/*#(+%6):#*+)#:)-(,*0#%"#

$&3*&')# *+/*# +/:# U&,$@30# :)<)3%8):# ,-# 7)6# Y-.3/-:4# ^/'</':# c%33).)# 6/(# "%&-:):# ,-#

Jaea4# c%R%-# f/*+)'# (8%@)# ()<)-# 3/-.&/.)(# 6)334# ^)# +/:# /$$)((# *%# Y&'%8)/-# ($,)-$)#

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

1

/

12

100%