D2891.PDF

A Global Strategy for the Progressive Control of Highly

Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, Rome)

World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE, Paris)

in collaboration with

World Health Organization (WHO, Geneva)

November 2005

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

FOREWORD

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

1

1.1 Emerging transboundary zoonotic diseases pose a serious

and continual threat to global economy and public health 1

1.2 HPAI is the most recently emerged transboundary zoonotic disease in Asia 1

2. WHY A GLOBAL STRATEGY?

2

2.1 Avian Influenza virus is constantly evolving with unpredictable results 3

2.2 The risk of a human pandemic 3

2.3 The livelihoods of the rural poor are threatened 3

2.4 Expansion of avian influenza to regions beyond Southeast and East Asia 4

2.5 Non-infected countries but at risk in East, South and Southeast Asia 4

2.6 Newly Infected countries in Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Caucasus 4

2.7 Globalized markets have caused HPAI to spread rapidly ` 4

2.8 Economic impact and poultry trade are in jeopardy 5

3. THE STRATEGY

5

3.1 Goal 5

3.2 Guiding principles 5

3.3 Approach 5

3.3.1 Infected countries in South, East and South East Asia 7

3.3.2 Newly infected countries in Asia and Europe 10

3.3.3 New non-infected countries at risk 11

4. OPPORTUNITIES FOR CONTROLLING HPAI

13

4.1 Methodologies and technologies for the control of HPAI are available 13

4.1.1 Diagnostic tools 13

4.1.2 Disease investigations facilities 13

4.1.3 Vaccines that are highly efficacious, safe and affordable 13

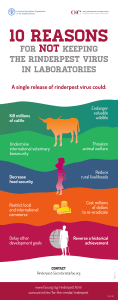

4.2 Control and eradication is feasible-learning from the success stories 14

4.3 National and Regional commitment to control HPAI is strong 14

4.4 International commitment to control HPAI is strong 14

4.5 Greater awareness of policy issues for HPAI control 15

5. CONSTRAINTS AND CHALLENGES TO HPAI CONTROL

15

5.1 Inadequate veterinary services-a major weakness 15

5.2 Stamping out and biosecurity measures are difficult to implement 16

5.3 More epidemiological information needed 16

5.4 Inadequate disease information systems 16

5.5 Domestic ducks are an HPAI reservoir 16

5.6 Disease has become endemic in several countries 17

5.7 Wildlife reservoir are a source of HPAI infection 17

5.8 Failure to base disease control planning and socio-economic impact assessment17

5.9.Weak linkages with public sector 17

5.10 Sustainable long-term regional coordination is badly needed 18

5.11 Financial resources remain inadequate 18

6. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE STRATEGY

18

6.1 National level 18

6.2 Regional level 19

6.3 International level 19

6.4 Developments of regional projects 20

7. TECHNICAL AND POLICY CONSIDERATIONS FOR

NATIONAL STRATEGIES

21

7.1 Disease control options and strategies 21

7.2 Epidemiology based control measures 21

7.3 Disease information systems 22

7.4 Targeting the source 22

7.5 Use of avian influenza vaccines 23

7.5.1 Vaccinating ducks – useful or questionable? 23

7.6 Person safety issues 24

7.7 Policy development 24

7.8 Pro-poor disease control programmes 24

7.9 Restructuring of the poultry sector 24

7.10 Compartmentalization and zoning 25

7.11 Collaboration with stakeholders 25

7.12 Capacity building 25

7.13 Applied research 26

8. OUTPUTS

26

9. IMPACTS

27

10. IMPLEMENTATION

27

11. MAJOR PARTNERS

27

11.1 Participating countries 27

11.2 Regional organizations 28

11.3 International organizations 28

11.4 National agriculture research extension systems 29

11.5 Private sector 29

12. REQUIRED INVESTMENT

29

13. RESOURCE MOBILIZATION

30

13.1 Source of funds 31

TABLES

1. Comparison of the five targeted countries for HPAI control 32

2. Estimated population engaged in backyard poultry production 32

3. Characteristics of four different poultry production systems 33

4. Indicative budget 34

5. Indicative financial support from various donors 38

6. Global Strategy – Logframe 40

FIGURES

1. Conceptual framework for HPAI control 42

2 HPAI situation between 2004 and 2005 43

3. Framework for implementation 44

APPENDICES

1. The GF-TADs – Executive summary 45

2. HPAI virus in Asia: Technical Information 47

3. Economic impacts of HPAI in some Southeast Asian countries 49

4. Vaccination for HPAI 50

5. Current FAO and other donor emergency assistance 52

6. Country profiles of HPAI 55

7. Key components of the strategy 58

8. OIE/FAO International Scientific Conference on Avian Influenza 62

9. Key partners in the implementation of the programme 66

10. HPAI and migratory birds 71

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

ADB Asian Development Bank

AGAH Animal Health Service of FAO

AGID agar gel immunodiffusion

ADB Asian Development Bank

AI avian influenza

APAARI Asia Pacific Association for Agriculture Research Institutes

APHCA Animal Production and Health Commission for Asia and the Pacific

ARIs advanced research institutions

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

ASEAN+3 Association of Southeast Asian Nations plus PR China, Japan and Republic of Korea

BSE bovine spongiform encephalopathy

CSF classical swine fever (also known as hog cholera)

DIVA differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals

DPR Democratic People’s Republic

EA East Asia

ECTAD Emergency Centre for Transboundary Animal Diseases

ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

EMPRES emergency prevention system

EU European Union

FAO Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

GDP gross domestic product

GF global framework

GF-TADs global framework for progressive control of transboundary animal diseases

GLEWS global early warning systems

GREP Global Rinderpest Eradication Programme

HPAI highly pathogenic avian influenza

JSDF Japan Social Development Fund

FMD foot-and-mouth disease

IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency

IDA International Development Association

LPAI Low pathogenic avian influenza

NARES national agricultural research and extension systems

NGO non-governmental organization

OFFLU OIE/FAO Network for avian influenza expertise

OIE World Organisation for Animal Health (Office International des Épizooties)

PCR polymerase chain reaction

PDR People’s Democratic Republic

PPE personal protective equipment

PR China People’s Republic of China

RAP Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific

RT-PCR reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

SA South Asia

SAARC South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

SADC Southern African Development Council

SAR Special Administrative Region

SARS severe acute respiratory syndrome

SEA Southeast Asia

TADs transboundary animal diseases

TCP technical cooperation project

UK United Kingdom

UMO United Maghreb Organization

USAID United States Agency for International Development

WB World Bank

WHO World Health Organization

WTO World Trade Organization

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

38

38

39

39

40

40

41

41

42

42

43

43

44

44

45

45

46

46

47

47

48

48

49

49

50

50

51

51

52

52

53

53

54

54

55

55

56

56

57

57

58

58

59

59

60

60

61

61

62

62

63

63

64

64

65

65

66

66

67

67

68

68

69

69

70

70

71

71

72

72

73

73

74

74

75

75

76

76

77

77

78

78

79

79

80

80

81

81

82

82

83

83

84

84

85

85

1

/

85

100%