Kinematics of faults between Subbetic Units during the Miocene

Tectonics / Tectonique

Kinematics of faults between Subbetic Units during

the Miocene (central sector of the Betic Cordillera)

Jesús Galindo-Zaldívar*, Patricia Ruano, Antonio Jabaloy, Manuel López-Chicano

Departamento de Geodinámica, Universidad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain

Received and accepted 20 November 2000

Communicated by Michel Durand-Delga

Abstract –The kinematic analysis of the low-angle faults that separate the major units of

the Subbetic Zone indicates two main stages of translations. In the first stage, of Burdiga-

lian to basal Tortonian age, the hanging walls moved toward the WSW, and thrusts devel-

oped in some sectors of the External Zones. Simultaneously, in the Internal Zones, the

activity of extensional detachments shows the same kinematics. In the second stage,

affecting up to basal Tortonian rocks, northwest-verging thrusts were active. The Subbetic

tectonic units probably underwent relative rotation during the development of these struc-

tures. © 2000 Académie des sciences / Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS

low-angle faults / kinematics / Miocene / Subbetic Zone / Internal Zones / Betic Cordillera

Résumé –Cinématique des failles entre les unités subbétiques pendant le Miocène

(secteur central de la cordillère Bétique). L’analyse cinématique des failles à faible

pendage qui séparent les unités principales du Subbétique indique deux étapes principa-

les de translations. Pendant la première étape, d’âge Burdigalien à Tortonien basal, les

blocs du toit se sont déplacés vers l’WSW et des chevauchements se sont produits dans

certains secteurs des zones externes. Cette activité tectonique fut simultanée de celle des

décollements extensionnels des zones internes à cinématique semblable. Pendant la

deuxième étape, qui affecte les formations jusqu’au Tortonien basal, se sont produits des

charriages dirigés vers le nord-ouest. Les unités tectoniques du Subbétique ont probable-

ment subi une rotation pendant le développement de ces structures. © 2000 Académie

des sciences / Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS

failles à faible pendage / cinématique / Miocène / zone Subbétique / zones internes / cordillère

Bétique

Version abrégée

1. Données d’ensemble

La cordillère Bétique, située à l’extrémité occidentale

de la chaîne alpine méditerranéenne, est divisée en

zones externes et zones internes (figure 1). Le bassin

du Guadalquivir sépare la cordillère Bétique du Massif

ibérique. La zone Prébétique et la zone Subbétique

constituent les zones externes et sont composées de

roches sédimentaires, d’âge Mésozoïque et Cénozoïque,

carbonatées en général, avec quelques intercalations de

roches volcaniques et subvolcaniques. Les zones inter-

nes sont formées par plusieurs complexes tectoniques

superposés, qui comprennent, en outre, des roches

paléozoïques et qui ont subi un métamorphisme alpin.

Le complexe Névado-Filabride est situé dans une posi-

tion structurale inférieure. Au-dessus est situé le com-

plexe Alpujarride, et par-dessus le tout se trouve le

complexe Malaguide. Les complexes de la Prédorsale,

de la Dorsale et d’Alozaina sont moins bien représentés

dans la zone étudiée. Entre les zones externes et inter-

nes sont situées des unités du sillon des Flyschs. Pen-

dant le Néogène et le Quaternaire, de grandes dépres-

sions se sont développées : l’une des principales est la

dépression de Grenade, remplie principalement de

roches sédimentaires du Tortonien au Quaternaire, et

de résidus du Miocène moyen et inférieur.

*Correspondence and reprints.

E-mail address: jgalindo@ugr.es (J. Galindo-Zaldívar).

811

C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 331 (2000) 811–816

© 2000 Académie des sciences / Éditions scientifiques et médicales Elsevier SAS. Tous droits réservés

S1251805000014841/FLA

Au cours des dernières années, la plupart des travaux

tectoniques ont étéconsacrés aux zones internes. Les

principales déformations ductiles et cassantes que l’on y

reconnaît sont associées àde grandes failles normales à

faible pendage, actives pendant le Miocène inférieur [8].

Dans le secteur central de la Cordillère, la faille de

Mecina a permis le déplacement vers l’ouest des Alpu-

jarrides par-dessus les Névado-Filabrides (figure 1).

Cette faille a produit des déformations ductiles dans les

Névado-Filabrides (linéations d’étirement, plis), qui ont

évoluéen ductiles-cassantes (clivages de crénulation

extensionnels) et en cassantes (failles et diaclases). En

revanche, les déformations dans les Alpujarrides ont été

principalement cassantes [6, 9]. Enfin, du Miocène supé-

rieur jusqu’à l’époque actuelle, des plis àgrand rayon

de courbure et des failles normales, généralement àfort

pendage, se sont créés.

Dans les zones externes, la cinématique des failles de

la zone Prébétique est relativement bien connue, avec

une tectonique en écailles, typique des nappes de

décollement des régions externes des orogènes. Dans

le secteur central de la cordillère Bétique, des chevau-

chements avec déplacement des blocs du toit vers le

nord-ouest ont étéidentifiés [5, 11]. Néanmoins, peu de

travaux ont étudiéla cinématique des failles séparant

les principales unités tectoniques de la zone Subbéti-

que. Les études disponibles sont généralement basées

sur l’analyse des plis internes des unités et sur les

reconstructions paléogéographiques, sans que les

microstructures associées aux contacts aient étéanaly-

sées en détail. La plupart des plis dans le Subbétique

ont des axes d’orientation ENE–WSW, ce qui a favorisé

l’hypothèse de déplacements des unités vers le NNW

ou vers le SSE. La plupart des recherches [7, 10, 14]

indiquent une première étape de charriage vers le

NNW. Ces chevauchements seraient déformés par des

plis de direction ENE–WSW, et par une phase posté-

rieure de rétrocharriages avec des déplacements vers le

SSE [7]. D’autres auteurs [10], ont considéréque la pre-

mière étape de charriage était dirigée vers le SSE, et

que les rétrocharriages auraient un sens de transport

vers le NNW. Les coupes équilibrées proposées dans le

Subbétique [1, 2], qui ont ététrès discutées, étaient

basées sur ces directions de transport. Une hypothèse

différente [4] a supposéque le Subbétique est une

grande structure en fleur, associéeàun décrochement

profond. Par ailleurs, les données paléomagnétiques

indiquent que la plupart des unités du Subbétique, sauf

la Sierra Gorda, ont subi des rotations horaires de près

de 60°, probablement pendant le Miocène [12, 13].

Le principal but de cette étude est de déterminer la

cinématique des mouvements entre les principales uni-

tés du Subbétique dans le secteur central de la cor-

dillère Bétique, àpartir d’observations de terrain.

D’autre part, on discutera la relation de cette cinémati-

que avec les failles àfaible pendage des zones internes.

2. Cinématique des contacts majeurs entre les

unités de la zone Subbétique

D’un point de vue structural, la zone Subbétique du

secteur central de la Cordillère est formée par trois uni-

tés tectoniques principales superposées et séparées par

des failles àfaible pendage (figure 1). Ces contacts

recoupent les plis d’axe ENE–WSW, observés dans

l’unitéSubbétique intermédiaire, au nord de la dépres-

sion de Grenade [15]. Les surfaces de faille sont généra-

lement recouvertes par des éboulis dus àla topogra-

phie de la région, forte et irrégulière. Il est seulement

possible d’observer directement les structures des

roches faillées dans quelques carrières, talus de routes,

ou vallées encaissées. Bien que ces observations soient

dispersées, elles couvrent toute la région. La cinémati-

que des failles àfaible pendage (figure 1)aétédéter-

minée par les structures observées sur les roches

faillées (figure 2). Les foliations cataclastiques, stries,

cisaillements Riedel, queues de trituration et croissances

de calcite indiquent au moins deux étapes de transla-

tion des blocs de toit: vers l’WSW et vers le NNW.

Dans la Sierra de Parapanda, on trouve des fibres de

calcite correspondant aux deux étapes de translation

(figure 2), qui indiquent que le mouvement vers le

NNW est le plus récent. L’âge des translations est déter-

minépar les données de terrain. Au nord-ouest de Loja,

la formation des «argiles àblocs »,d’âge Burdigalien [3],

est située au-dessus de l’unitéSubbétique intermédiaire

par le biais d’une faille àfaible pendage, avec déplace-

ment du bloc du toit vers le sud-ouest. Les roches tor-

toniennes fossilisent cette faille, mais les dépôts burdi-

galiens et tortoniens sont chevauchés par l’unité

Subbétique supérieure, qui se déplace vers le NNW

(figures 1 et 2).

Par ailleurs, dans la partie méridionale de la Sierra

Gorda, le charriage du Subbétique sur les unités des

Flyschs montre également des structures qui indiquent

que le déplacement du bloc du toit se fait vers l’WSW.

Les roches du Tortonien, dans la dépression de Gre-

nade et àproximitéd’Alfarnate, fossilisent ce contact.

Les roches faillées des charriages dans l’unitéSubbé-

tique supérieure, dans la Sierra Gorda, indiquent des

déplacements des blocs du toit vers l’WSW (figures 1 et

2). Cette région, selon les études paléomagnétiques [12,

13], n’a pas subi de rotations importantes, et la direc-

tion de translation des charriages est presque perpendi-

culaire aux axes des plis et àla direction des failles

inverses (figure 1).

3. Discussion et conclusions

Les observations de terrain indiquent que deux éta-

pes principales de translation apparaissent par l’analyse

des failles àfaible pendage de la zone Subbétique. Ces

translations sont superposées àdes plis antérieurs. Pen-

dant l’étape initiale de translation, d’âge Burdigalien à

Tortonien, les blocs du toit se sont déplacés vers

l’WSW. Le caractère compressif de cette déformation

812

J. Galindo-Zaldívar et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 331 (2000) 811–816

peut seulement être observédans la Sierra Gorda : les

roches du Subbétique y sont superposées aux unités

des Flyschs et les directions d’axes des plis et des

failles inverses sont perpendiculaires àla direction de

translation des chevauchements. Dans les autres affleu-

rements de la zone Subbétique, on n’observe pas de

surfaces de référence horizontales préalables qui per-

mettent de déterminer si les translations vers l’ouest

correspondent àdes failles normales àfaible pendage

ou àdes failles inverses. Cependant, si l’on tient

compte des études paléomagnétiques [12, 13], l’unité

Subbétique intermédiaire a subi une rotation horaire

pendant le Miocène, et l’orientation initiale serait proba-

blement semblable àcelle de la Sierra Gorda, qui

appartient àl’unitéSubbétique supérieure, qui n’a pas

subi de rotation. Les plis se sont probablement formés

avec des axes orientés nord–sud, àpeu près orthogo-

naux au sens des translations. Du fait de la translation

vers l’ouest des unités subbétiques par rapport au Mas-

sif ibérique, l’unitéSubbétique intermédiaire pourrait

avoir tournéprogressivement, tout en étant encadréeau

mur et au toit par des failles, avec déplacement des

blocs du toit vers l’ouest.

Durant cette période, la faille de Mecina a étéactive

dans les zones internes [6, 8, 9]. Par conséquent, au

Miocène inférieur, tandis que les zones internes ont

subi une extension, et que des failles normales àfaible

pendage, avec déplacement des blocs du toit vers

l’WSW, y étaient actives, une compression avec charria-

ges àvergence WSW eut lieu dans les zones externes.

Ces structures compressives et extensives peuvent être

reliées en profondeur, puisque les failles àfaible pen-

dage des zones internes s’inclinent vers le nord-ouest,

tandis que celles des zones externes s’inclinent vers le

sud-est, toutes deux ayant la même cinématique et le

même âge. Cependant, les données géophysiques et

géologiques existantes ne sont pas détaillées et ne per-

mettent pas de déterminer les rapports exacts entre ces

deux types d’accidents.

Les structures associées aux translations vers l’ouest

et le contact entre les zones externes et internes sont

fossilisées par les roches tortoniennes dans la dépres-

sion de Grenade. Les étapes de la translation vers le

nord-ouest dans le Subbétique sont postérieures au Tor-

tonien basal. Ces translations peuvent être corrélées

avec les charriages vers le nord-ouest, qui affectent les

unitésduPrébétique [11], mais ces derniers doivent

avoir un déplacement limité, car dans aucune fenêtre

tectonique n’affleurent de matériaux tortoniens.

L’étape principale des translations, avec déplacement

des blocs du toit vers l’WSW, n’aétéprise en considé-

ration dans aucun modèle tectonique antérieur d’évolu-

tion des zones externes. Ces translations devront être

prises en compte dans les modèles proposésàl’avenir,

et devront également considérer le caractère simultané

des déformations compressives dans les zones externes

et des déformations extensives dans les zones internes,

avec la même direction et dans des secteurs adjacents.

Par ailleurs, les deux étapes de translation ont des

directions obliques, l’une par rapport àl’autre, ce qui

remet en question, dans cette région, la validitéde l’uti-

lisation des méthodes des coupes balancées avec une

seule direction de transport.

1. General setting

The Betic Cordillera, located in the western end of the

Mediterranean alpine chain, is divided into External Zones

and Internal Zones (figure 1). The Guadalquivir Basin

separates the Betic Cordillera from the Iberian Massif. The

Prebetic Zone and the Subbetic Zone constitute the Exter-

nal Zones; they are composed of Mesozoic and Cenozoic

sedimentary rocks, generally limestones and dolostones,

with scarce intercalations of volcanic and subvolcanic

rock. Several superposed tectonic complexes that include

Palaeozoic rocks, which have undergone alpine metamor-

phism compose the Internal Zones. The Nevado-Filabride

Complex is located in the lowest structural position. Above

it is situated the Alpujarride Complex and, above the two,

in turn, is the Maláguide Complex. The Predorsal, Dorsal

and Alozaina complexes are not as well represented.

Between the External and Internal Zones are the Flysch

swell units. During the Neogene and Quaternary, large

depressions developed: one of the main ones is the

Granada Depression, filled mainly by Tortonian to Quater-

nary sedimentary rocks and scarcer rocks of Middle and

Early Miocene age.

In recent years, most tectonic research has studied the

Internal Zones. The main ductile and brittle deformations

that are recognized in these rocks are associated with the

large, active low-angle normal faults of the Early Miocene

[8]. In the central sector of the Cordillera, the Mecina Fault

moved the Alpujarride complex westwards upon the

Nevado-Filabride complex (figure 1). This fault produced

ductile deformations (stretching lineations, folds) on the

Nevado-Filabride rocks that evolved to ductile/brittle

(extensional crenulation cleavage) and to brittle condi-

tions (faults and joints). Meanwhile, the deformation in the

Alpujarride was preferentially brittle [6, 9]. From Late

Miocene to the Present, folds with great radia and high-

angle normal faulting took place in general.

In the External Zones, the kinematics of the contacts of

Prebetic Zone, with a typical imbricate thrust system

geometry, are relatively well known. In the central sector

of the cordillera, thrusts with displacement of the hanging

walls towards the northwest have been identified [5, 11].

Nevertheless, little research has focused on the kinematics

of the faults between the main tectonic units of the Sub-

betic Zone. Available studies are generally based on the

analysis of internal folds of the units and on palaeogeo-

813

J. Galindo-Zaldívar et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 331 (2000) 811–816

graphic reconstructions, without examining in detail the

microstructures associated with these contacts. Most of the

folds in Subbetic rocks show ENE–WSW axes, supporting

the hypotheses that propose displacements of the units

towards the NNW or the SSE. Most of these authors [7, 14,

15] indicate an initial stage of thrusting towards the NNW.

Such thrusting would have been affected by folds with

ENE–WSW trends and by a later phase of backthrusting

with displacement toward the SSE [7]. Other authors, such

as [10], postulate that the first stage of thrusting was SSE-

vergent, and that the backthrusting had a NNW transport

sense. Balanced sections of the Subbetic units [1, 2]

–strongly debated –have been made based on these

directions of transport. A different hypothesis has been pro-

posed [4]: the Subbetic units are in a huge flower structure

associated at depth with a transcurrent fault. Meanwhile,

palaeomagnetic data appear to indicate that almost all of

the units of the Subbetics, with the exception of Sierra

Gorda, underwent clockwise rotations of nearly 60°dur-

ing the Miocene [12, 13].

The main aim of this study is to determine, on the

basis of field observations, the kinematics between the

main units of the Subbetic in the central sector of the

Betic Cordillera. Their relationship with the low-angle

faults of the Internal Zones will also be discussed.

2. Kinematics of the major contacts

between units of the Subbetic Zone

From a structural point of view, the Subbetic Zone in

the central Betic Cordillera is formed by three super-

posed major tectonic units separated by low-angle faults

(figure 1). The low-angle faults cut the ENE–WSW folds

observed in the Intermediate Unit, to the north of the

Granada Depression [15].

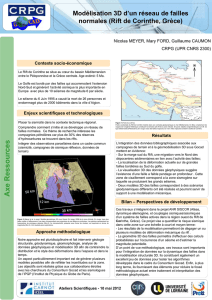

Figure 1. General map of the Betic Cordillera (a), and detailed map of the central sector (b). 1, Upper Miocene-Quaternary sedimentary rocks.

2, Upper Subbetic Unit. 3, Intermediate Subbetic Unit (the whole Subbetic Zone in part a). 4, Lower Subbetic Unit. 5, Prebetic. 6, Oligocene–

Lower Miocene sedimentary rocks, including flysch and olistostroms. 7, Campo de Gibraltar Flyschs units. 8, Predorsal, Dorsal and Maláguide

complexes. 9, Alpujarride Complex. 10, Nevado-Filabride Complex. 11, unconformity. 12, fault. 13, low-angle fault. 14, reverse fault. 15,

anticlinal. 16, synclinal. 17, translation of the hanging walls toward the WSW in low-angle faults of External Zones. 18, translation of the

hanging walls toward the NW in low-angle faults of External Zones. 19, translation of the hanging walls toward the WSW in low-angle faults

of Internal Zones.

Figure 1. Carte générale de la cordillère Bétique (a), et carte détaillée du secteur central (b). 1, roches sédimentaires du Miocène

supérieur–Quaternaire. 2, unitéSubbétique supérieure. 3, unitéSubbétique intermédiaire (tout le Subbétique, cartouche a). 4, unitéSubbéti-

que inférieure. 5,Prébétique. 6, roches sédimentaires de l’Oligocène–Miocène inférieur, incluant flyschs et olistostromes. 7, unitésdeflyschs

du Campo de Gibraltar. 8, complexes de la Prédorsale, de la Dorsale et du Malaguide. 9, complexe Alpujarride. 10,complexeNévado-

Filabride. 11, discordance. 12, faille. 13, faille àfaible pendage. 14, faille inverse. 15, anticlinal. 16, synclinal. 17, mouvement vers l’WSW

des blocs du toit dans les failles àfaible pendage des zones externes. 18, mouvement vers le nord-ouest des blocs du toit dans les failles à

faible pendage des zones externes. 19, mouvement vers le l’WSW des blocs du toit dans les failles àfaible pendage des zones internes.

814

J. Galindo-Zaldívar et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 331 (2000) 811–816

The fault surfaces are generally covered by debris due

to the irregular topography of the region. It is only pos-

sible to observe the fault features directly in some quar-

ries, road cuttings, or deep valleys. Although the points

of observation are far from one another, they cover the

entire region. The kinematics of low-angle faults (figure

1) were determined by the structures observed on fault

rocks (figure 2). The cataclastic foliations, striae, Riedel

shears, crushing tails and calcite growths indicate at

least two stages of translation of the hanging wall block:

towards the WSW and to the NNW.

In the Sierra de Parapanda outcrop, calcite fibres corre-

sponding to both stages of translation (figure 2) are seen;

they indicate that the movement towards the NNW is the

most recent. Field data allow the age of the translations to

be deduced. To the north-west of Loja, the ‘argiles àblocs’

formation of Burdigalian age [3] is located above the rocks

of the Intermediate Subbetic Unit by a low-angle fault with

WSW displacement of the hanging wall. Tortonian rocks

fossilize this fault. Both Burdigalian and Tortonian rocks

are thrusted by the Upper Subbetic Unit that moves

towards the NNW (figures 1 and 2).

South of Sierra Gorda, the thrust of the Subbetic rocks

atop the Flysch units also features structures that indi-

cate displacement of the hanging wall block toward the

WSW. Tortonian rocks in the Granada Depression and

in the proximity of Alfarnate fossilize this contact.

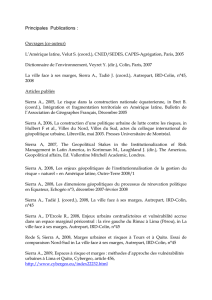

Figure 2. Low-angle faults and fault rock structures. Sierra de Parapanda (a) and Sierra Gorda (b) low-angle faults superposing Jurassic

limestones over Cretaceous marls. c, calcite fibres corresponding to two stages of translation in the Sierra de Parapanda. d, fault rock

structures showing a top-to-the-west motion in Sierra Gorda (d), Sierra de Parapanda (e) and Colomera (f)

Figure 2. Failles àfaible pendage et structures des roches faillées. Failles àfaible pendage de la Sierra de Parapanda (a) et de la Sierra

Gorda (b), qui amènent la superposition des calcaires jurassiques aux marnes crétacées. c,fibres de calcite correspondant aux deux étapes

de translation dans la Sierra de Parapanda. Structures des roches faillées montrant un mouvement vers le l’WSW des blocs du toit àla Sierra

Gorda (d), àla Sierra de Parapanda (e)etàColomera (f).

815

J. Galindo-Zaldívar et al. / C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes / Earth and Planetary Sciences 331 (2000) 811–816

6

6

1

/

6

100%