Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal Revue canadienne de soins

Canadian Oncology

Nursing Journal

Revue canadienne

de soins infirmiers

en oncologie

The ofcial publication of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology

La publication ofcielle de l’Association canadienne des inrmières en oncologie

Fall/Automne 2014 ISSN: 1181-912X

Volume 24, No. 4 PM#: 40032385

Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal

Revue canadienne de soins infirmiers en oncologie

A publication of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology—Une publication de l’Association canadienne des infirmières en oncologie

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40032385. RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO:

Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology, 375 West 5th Avenue, Suite 201, Vancouver, BC, V5Y 1J6, E-mail: [email protected]

Fall/Automne 2014

Volume 24, No. 4

Articles

Table of Contents/Table des matières

233 Editorial

236 Éditorial

Communiqué

312 President’s message: CANO/ACIO Strategic Directions

2013–2016

313 Message de la présidente : Orientations stratégiques

2013–2016 de l’ACIO/CANO

313 Director at Large—Education

314 Conseillère générale—Éducation

315 Director at Large—Professional Practice

316 Conseillère générale—Pratique professionnelle

317 Complementary Medicine Special Interest Group

321 Groupe d’intérêts spéciaux Pratiques complémentaires

325 DAL—Membership

325 Conseillère générale—

Service aux membres

326 Nurse to know: Shawne Gray

326 Une inrmière qu’il fait bon connaître : Shawne Gray

327 Nurse to know: Shari Moura

329 Une inrmière qu’il fait bon connaître : Shari Moura

331 Nurse to know: Philiz Goh

332 Une inrmière qu’il fait bon connaître : Philiz Goh

Features/Rubriques

237 Patient perspective

239 Perspective d’un patient

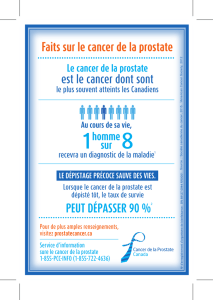

287 Resource review

288 Examen de ressource

289 Ask an ethicist

290 Demandez à un éthicien

291 Book review

292 Critique de livre

293 Resources for patients and family members

294 Ressources pour les patients et leur famille

295 Reections on research

297 Réexions sur la recherche

299 International perspectives

300 Perspectives internationales

302 Quality improvement

306 Amélioration de la qualité

241 Using a web-based decision support intervention to facilitate patient-physician communication at prostate

cancer treatment discussions

by B. Joyce Davison, Michael Szafron, Carl Gutwin, and Kishore Visvanathan

248 Une intervention en ligne de soutien à la décision pour faciliter la communication patient-médecin en lien

avec le traitement du cancer de la prostate

par B. Joyce Davison, Michael Szafron, Carl Gutwin et Kishore Visvanathan

256 A biopsychosocial approach to sexual recovery after prostate cancer treatment: Suggestions for oncology

nursing practice

by Lauren M. Walker, Andrea M. Beck, Amy J. Hampton, and John W. Robinson

264 Une approche biopsychosociale au rétablissement sexuel après le traitement du cancer de la prostate :

suggestions pour la pratique infirmière en oncologie

par Lauren M. Walker, Andrea M. Beck, Amy J. Hampton et John W. Robinson

272 The sexual and other supportive care needs of Canadian prostate cancer patients and their partners:

Defining the problem and developing interventions

by Deborah L. McLeod, Lauren M. Walker, Richard J. Wassersug, Andrew Matthew, and John W. Robinson

279 Les besoins de nature sexuelle et en soins de soutien des Canadiens atteints du cancer de la prostate et de

leurs partenaires : définition du problème et développement des interventions

par Deborah L. McLeod, Lauren M. Walker, Richard J. Wassersug, Andrew Matthew et John W. Robinson

CONJ • RCSIO Fall/Automne 2014

Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal

Revue canadienne de soins infirmiers en oncologie

Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal/Revue canadienne de soins infirmiers en oncologie is a refereed journal.

Editor-in-Chief Margaret I. Fitch, RN, PhD, 207 Chisholm Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M4C 4V9.

Phone: 416-690-0369; Email: [email protected]

Associate Editors Janice Chobanuk, RN, BScN, MN, CON(C)—books/media Jeanne Robertson, RN, B.Arts, BScN, MBA—French materials

Pat Sevean, RN, BScN, EdD—features Sharon Thomson, RN, MSc, BA, MS—manuscript review

Sally Thorne, RN, PhD, FCAHS—research

Reviewers Nicole Allard, RN, MSN, PhD, Bilingual, Maxine Alford, RN, PhD, Karine Bilodeau, inf., PhD(C), French, Joanne Crawford, RN, BScN,

CON(C), MScN, PhD(c), Dauna Crooks, DNSc, MScN, BScN, Jean-François Desbiens, inf., PhD, French, Sylvie Dubois, inf., PhD, Bilingual,

Corsita Garraway, EN(EC), MScN, CON(C), CHPH, Vicki Greenslade, RN, PhD, Virginia Lee, RN, BA, MSC(A), PhD, Bilingual,

Manon Lemonde, RN, PhD, Bilingual, Maurene McQuestion, RN, BA, BScN, MSc, CON(C), Beth Perry, RN, PhD, Karyn Perry, BSN, MBA,

Patricia Poirier, PhD, RN, Dawn Stacey, RN, MScN, PhD, (CON), Jennifer Stephens, RN, BSN, MA, OCN, Pamela West, RN, MSc, ACNP,

CON(C), CHPCN(C), Kathleen Willison, RN, MSc, CVAA(c), CHPCN(c), Patsy Yates, RN, PhD

Managing Editor Heather Coughlin, 613-735-0952, fax 613-735-7983, e-mail: [email protected]

Production The Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal is produced in conjunction with Pappin Communications, The Victoria Centre,

84 Isabella Street, Pembroke, Ontario K8A 5S5, 613-735-0952, fax 613-735-7983, e-mail [email protected], and

Vice Versa Translation, 144 Werra Rd., Victoria, British Columbia V9B 1N4, 250-479-9969, e-mail: [email protected]

Statement The Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal is the official publication of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology, and is

of purpose directed to the professional nurse caring for patients with cancer. The journal supports the philosophy of the national association.

The philosophy is: “The purpose of this journal is to communicate with the members of the Association. This journal currently acts as

a vehicle for news related to clinical oncology practice, technology, education and research. This journal aims to publish timely papers,

to promote the image of the nurse involved in cancer care, to stimulate nursing issues in oncology nursing, and to encourage nurses to

publish in national media.” In addition, the journal serves as a newsletter conveying information related to the Canadian Association

of Nurses in Oncology, it intends to keep Canadian oncology nurses current in the activities of their national association. Recognizing

the value of nursing literature, the editorial board will collaborate with editorial boards of other journals and indexes to increase the

quality and accessibility of nursing literature.

Indexing The Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal/Revue canadienne de soins infirmiers en oncologie is registered with the National Library

of Canada, ISSN 1181-912X, and is indexed in the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, (CINAHL), the

International Nursing Index and Medline.

Membership All nurses with active Canadian registration are eligible for membership in CANO. Contact the CANO national office. Refer to the

Communiqué section for name and contact information of provincial representatives.

Subscriptions The journal is published quarterly in February, May, August and November. All CANO members receive the journal. For

non-members, yearly subscription rates are $119.77 (HST included) for individuals, and $131.88 (HST included) for institutions.

International subscriptions are $156.11 (HST included). Payment must accompany all orders and is not refundable. Make cheques

payable to CANO-CONJ and send to the CANO national office. Notices and queries about missed issues should also be sent to the

CANO national office. Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology, 570 West 7th Avenue, Suite 400, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1B3,

www.cano-acio.ca; telephone: 604-630-5493; fax: 604-874-4378; email: [email protected]

Author Guidelines for authors are usually included in each issue. All submissions are welcome. At least one author should be a

Information registered nurse, however, the editor has final discretion on suitability for inclusion. Author(s) are responsible for acknowledging all

sources of funding and/or information.

Language Policy/ The Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal is officially a bilingual publication. All journal content submitted and reviewed by the editors

Politique will be printed in both official languages. La Revue canadienne de soins infirmiers en oncologie est une publication officiellement

linguistique bilingue. Le contenu proprement dit de la Revue qui est soumis et fait l’objet d’une évaluation par les rédactrices est publié dans les

deux langues officielles.

Advertising For general advertising information and rates, contact Heather Coughlin, Advertising Manager, Pappin Communications, 84 Isabella St.,

Pembroke, Ontario K8A 5S5, 613-735-0952, fax 613-735-7983, e-mail [email protected]. All advertising correspondence and

material should be sent to Pappin Communications. Online rate card available at: www.pappin.com

Opinions expressed in articles published are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the view of the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology or

the editorial board of the Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. Acceptance of advertising does not imply endorsement by CANO or the editorial board of CONJ.

All rights reserved. The law prohibits reproduction of any portion of this journal without permission of the editor.

Fall/Automne 2014

Volume 24, No. 4

CONJ • RCSIO Fall/Automne 2014 233

As guest editor, I am

excited to be a part of this

first special, themed issue

of CONJ. Our focus here

is on prostate cancer and,

particularly, the sexual and

supportive care challenges,

which are many. It is an area of practice

in which I have been involved for more

than 10 years, as an educator, researcher

and practitioner. During the time that I

have worked with couples affected by

prostate cancer, I have been disturbed

by the ways in which men’s—and their

spouse’s or partner’s—needs have been

poorly and inconsistently addressed by

our health care systems. Very often I

have encountered couples who have suf-

fered silently (or even not so silently) for

years before I see them. They tell me sto-

ries of struggling alone, particularly try-

ing to figure out the sexual challenges,

or of giving up, drifting apart and strug-

gling with depression. The abandonment

of a sexual relationship can lead to a pro-

found loss of intimacy in the relationship

overall for many couples. I have heard

also from many partners who feel com-

pletely overlooked, alone, or even worse,

experience their concerns dismissed

by health care professionals (HCPs). It

seems that HCPs often believe that men

affected by prostate cancer “do well” and

“have few issues”, even with such diffi-

cult treatments as androgen depriva-

tion therapy. Of course, some do; though

many do not, as the articles in this issue

describe.

During my time as a faculty mem-

ber with the Canadian Association of

Psychosocial Oncology’s IPODE (www.

ipode.ca) project, I have also heard

nurses express shock and surprise after

seeing presentations like Ross Gray’s

“No Big Deal” or reading his photo story

“Simon’s Romantic Evening”. One nurse

(who I consider to be an excellent cli-

nician, by the way) told me “After 10

years as an oncology nurse working

with men in this area, I had absolutely

no idea (her emphasis) what they were

going through”. Understandably, she

was distressed, but also, I hope, pro-

pelled to start making changes in her

practice.

Participants in seminar discussions

about sexuality and cancer sometimes

question the need to address sexual

health concerns with this (or other) can-

cer populations. The argument goes

something like this… We are not experts

in sexual health; beyond giving some basic

information I don’t think it is our role to

be “sex therapists”. There are experts

in the community who can do this.” To

this, I offer a couple of responses. First,

the sexual health problems that peo-

ple encounter after cancer treatment are

an iatrogenic effect; given that we have

caused the problem, do we not have

some obligation to address it? Secondly,

while there are experts to refer peo-

ple to in some communities, these are

not plentiful and, indeed, are exception-

ally scarce in some communities. Where

they do exist, the services can be expen-

sive. Further, some of my private practice

colleagues tell me they are not well pre-

pared to address sexual aspects of can-

cer. Furthermore, most of the problems

(in the vicinity of 80% according to one

study by Schover) do not require the ser-

vices of a sex therapist, but can be well

addressed through education and coach-

ing by HCPs who have some training in

the area. I think we have an obligation to

recognize the issues and do something to

address them.

Things are changing in Canada

though. Psychosocial distress screen-

ing has become a priority focus for prac-

tice change in many centres, and sexual

health seems to be getting a lot of atten-

tion, judging by the interest in courses

like IPODE’s Sexual Health Counselling

in Cancer courses and commitments by

agencies to purchase bulk discounts for

their staff. Sexual health is no longer seen

as everyone’s and no one’s responsibility.

Rather, more and more nurses are finding

ways to ask about concerns in this area

and to address or refer people who need

help.

Not all the concerns are about sex-

uality, of course; there are a myriad of

serious effects of treatments such as

androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), for

example, and few standardized programs

for helping men and partners to address

these. The distress men experience while

on ADT can be, perhaps often is, pro-

found. Body feminization, shrinking geni-

tals and loss of libido and sexual function

have an effect on how men experience

being a man, whether or not they wished

to be, or were sexually active. There are

many physical effects such as increased

cardiovascular risk that are obviously

important, too.

In this issue, we have three articles

addressing various aspects of pros-

tate cancer and an editorial by Richard

Wassersug, a prostate cancer patient,

scientist and lead author on the new

book Androgen Deprivation Therapy:

An Essential Guide for Prostate Cancer

Patients and Their Partners (www.

lifeonADT.com). Wassersug, humor-

ously and frankly, highlights for us

some of the “hits” and “misses” in his

interactions with nurses during his care.

We hope our readers find the articles

both interesting and useful in informing

their practice.

Deborah McLeod,

Guest Editor

Guest Editorial

Deborah L. McLeod, Dalhousie University, School of Nursing and Capital Health/QEII

Cancer Care Program, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

9

10

10

11

11

12

12

13

13

14

14

15

15

16

16

17

17

18

18

19

19

20

20

21

21

22

22

23

23

24

24

25

25

26

26

27

27

28

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

32

33

33

34

34

35

35

36

36

37

37

38

38

39

39

40

40

41

41

42

42

43

43

44

44

45

45

46

46

47

47

48

48

49

49

50

50

51

51

52

52

53

53

54

54

55

55

56

56

57

57

58

58

59

59

60

60

61

61

62

62

63

63

64

64

65

65

66

66

67

67

68

68

69

69

70

70

71

71

72

72

73

73

74

74

75

75

76

76

77

77

78

78

79

79

80

80

81

81

82

82

83

83

84

84

85

85

86

86

87

87

88

88

89

89

90

90

91

91

92

92

93

93

94

94

95

95

96

96

97

97

98

98

99

99

100

100

101

101

102

102

103

103

104

104

105

105

106

106

107

107

108

108

1

/

108

100%